Soaring drug prices could bar access to future coronavirus treatments

by Mona Chalabi - The Guardian - May 11, 2020

Existing drugs may help us get through the coronavirus pandemic while we wait for a vaccine, but high pricing by pharmaceutical companies will probably mean that, even if these drugs are proven to be effective, many sick people will still be prevented from getting treatment.

A study published this month in the Journal of Virus Eradication looked at nine of the drugs that have been identified as possible Covid-19 treatments and are in various stages of clinical trials globally. The team of researchers looked at how much each of the drugs is sold for in countries where data was available. Then they calculated what a generic version of these drugs might cost.

For example, a course of sofosbuvir (a drug currently used to treat hepatitis C) costs around $5 to make but the current list price in the US is $18,610.

Pirfenidone, a drug used for lung fibrosis, costs around $31 for a 28-day treatment course. In the US, a course is priced at $9,606, or $6,513 if patients are able to access it through the Department of Veterans Affairs. Though the US tops the list, the list price of this drug is still expensive elsewhere - a course costs $2,561 in the UK and $2,344 in France.

Pharmaceutical companies often defend their pricing by claiming that their costs are incredibly high. However, when calculating the price of a generic version of the drug, the researchers factored in export costs, taxes and even a 10% profit margin.

In some cases, pharmaceutical companies have minimized their costs by receiving government subsidies. Take remdesivir, a drug which has been touted by the US government’s top infectious disease expert, Dr Anthony Fauci, a claim later tempered in the British Medical Journal, where researchers expressed the need for caution about the drug’s efficacy.

Gilead Sciences, the company that makes remdesivir, benefited from at least $79m in US government funding. Despite the fact that US taxpayers have helped to develop the drug, Gilead announced it would no longer provide emergency access to it. Then, after widespread criticism, the company announced this week it would donate its entire stockpile of the drug to government.

In late March, the Food and Drug Administration gave Gilead “orphan” drug status, meaning the company has the right to profit exclusively for seven years from the sale of remdesivir. Normally, this drug status is reserved for treating rare diseases, not ones such as as Covid-19, for which more than 1 million people in the US have tested positive (and many more have been infected but not tested).

Gilead, which made $5bn in profit last year, has close ties to the US administration. Between 2011 and 2017, Joe Grogan lobbied for Gilead. He now serves on the White House coronavirus taskforce.

Speaking on the phone after a shift at a London hospital, one of the study’s authors, Dr Jacob Levi, explained: “There has been a long history of big pharmaceutical companies charging unnecessary and unwarranted high prices for medications, even if they actually spent very little on research and development for that medication.”

Levi added: “That’s been extremely common with infectious disease medications in the past, like hepatitis and HIV, and we can’t let it happen with medications for Covid-19. Otherwise, hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths would occur and healthcare inequality amongst the poor will worsen.”

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/11/soaring-drug-prices-could-bar-access-to-future-coronavirus-treatments

Up to 43m Americans could lose health insurance amid pandemic, report says

by Jessica Glenza - The Guardian - May 10, 2020

As many as 43 million Americans could lose their health insurance in

the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, according to a new report from

the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Urban Institute.

Prior to the pandemic, 160 million Americans, or roughly half the population, received their medical insurance through their job. The tidal wave of layoffs triggered by quarantine measures now threatens that coverage for millions.

Up to 7 million of those people are unlikely to find new insurance as poor economic conditions drag on, researchers at the Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation thinktanks predict.

Such enormous insurance losses could dramatically alter America’s healthcare landscape, and will probably result in more deaths as people avoid unaffordable healthcare.

“The status quo is incredibly inefficient, it’s incredibly unfair, it’s tied to employment for no real reason,” said Katherine Hempstead, a senior policy adviser for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “This problem exposes a lot of the inadequacies in our system.”

If the pandemic results in a 20% unemployment rate, as some analysts expect, researchers at the Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) predict anywhere from 25 to 43 million people could lose health insurance. Many will use social safety nets to obtain insurance, including Medicaid, the public health insurance program for low-income people. However, eligibility criteria varies from state to state, with more restrictions in Republican-led states.

“It’s incredibly segmented and every state has a different story,” said Hempstead. “There’s 50 different experiences.”

Christine Mohn, 51, lives in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and worked as a physical therapist. She lost her job of 18 years when her company was bought out in November 2019.

“You walk in the door one day, and they said: ‘Your job is not here and neither is your health insurance – bye,’” Mohn said.

For several months, Mohn, her husband and college-age daughter relied on a program called Cobra, which allows Americans to continue the benefits they once received from a job. But the benefits came at a steep cost. Mohn paid $1,700 a month for insurance using a line of credit on her mortgage until April 2020, when she finally got a new job.

Mohn only worked two weeks before the job indefinitely furloughed its workers because the pandemic closed down all non-urgent health services.

The company that furloughed Mohn allowed her to keep her health insurance, even though it is under no obligation to do so. The insurance costs Mohn $400 a month, and after four weeks she still has not received her first unemployment check. When she finally does go back to work, she said: “I can get to paying off my line of credit I’ve been living off.”

Of those who lose employer-based insurance, an estimated 7 million Americans will remain uninsured, and will lack access to healthcare during the worst pandemic in a century, RWJF predicted. Another 30 million people lacked insurance even before the pandemic, according to the Urban Institute.

“You have people who think they have an infectious disease, but they don’t want to come forward to get tested or get treatment because they’re so worried about what kind of financial liabilities they will have,” said Hempstead. “This problem exposes, really, a lot of the inadequacies in our system.”

Emily Jones, 22, is one of them. She lives with her mother and sister in Flushing, Michigan, and is a cancer survivor. People’s Action, an advocacy group, said her insurance lapsed when she missed renewal paperwork just as the pandemic set in. Now, she is without insurance even as her mother is an essential worker.

Estimating the number of people who lack insurance is a complicated task. America’s fragmented health system lacks a single metric for how many people are shut out. Some researchers believe insurance losses will be low relative to job losses, because many lacked insurance despite working.

“The American healthcare financing system was not built to withstand the combined impact of a pandemic and a recession,” said Dr Adam Gaffney, the president of Physicians for a National Health Program. PNHP advocates for a single-payer health system in the US, similar to the NHS. “It’s inevitable that people will die because they can’t get the care they need, because of the looming recession.”

Prior to the pandemic, 160 million Americans, or roughly half the population, received their medical insurance through their job. The tidal wave of layoffs triggered by quarantine measures now threatens that coverage for millions.

Up to 7 million of those people are unlikely to find new insurance as poor economic conditions drag on, researchers at the Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation thinktanks predict.

Such enormous insurance losses could dramatically alter America’s healthcare landscape, and will probably result in more deaths as people avoid unaffordable healthcare.

“The status quo is incredibly inefficient, it’s incredibly unfair, it’s tied to employment for no real reason,” said Katherine Hempstead, a senior policy adviser for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “This problem exposes a lot of the inadequacies in our system.”

If the pandemic results in a 20% unemployment rate, as some analysts expect, researchers at the Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) predict anywhere from 25 to 43 million people could lose health insurance. Many will use social safety nets to obtain insurance, including Medicaid, the public health insurance program for low-income people. However, eligibility criteria varies from state to state, with more restrictions in Republican-led states.

“It’s incredibly segmented and every state has a different story,” said Hempstead. “There’s 50 different experiences.”

Christine Mohn, 51, lives in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and worked as a physical therapist. She lost her job of 18 years when her company was bought out in November 2019.

“You walk in the door one day, and they said: ‘Your job is not here and neither is your health insurance – bye,’” Mohn said.

For several months, Mohn, her husband and college-age daughter relied on a program called Cobra, which allows Americans to continue the benefits they once received from a job. But the benefits came at a steep cost. Mohn paid $1,700 a month for insurance using a line of credit on her mortgage until April 2020, when she finally got a new job.

Mohn only worked two weeks before the job indefinitely furloughed its workers because the pandemic closed down all non-urgent health services.

The company that furloughed Mohn allowed her to keep her health insurance, even though it is under no obligation to do so. The insurance costs Mohn $400 a month, and after four weeks she still has not received her first unemployment check. When she finally does go back to work, she said: “I can get to paying off my line of credit I’ve been living off.”

Of those who lose employer-based insurance, an estimated 7 million Americans will remain uninsured, and will lack access to healthcare during the worst pandemic in a century, RWJF predicted. Another 30 million people lacked insurance even before the pandemic, according to the Urban Institute.

“You have people who think they have an infectious disease, but they don’t want to come forward to get tested or get treatment because they’re so worried about what kind of financial liabilities they will have,” said Hempstead. “This problem exposes, really, a lot of the inadequacies in our system.”

Emily Jones, 22, is one of them. She lives with her mother and sister in Flushing, Michigan, and is a cancer survivor. People’s Action, an advocacy group, said her insurance lapsed when she missed renewal paperwork just as the pandemic set in. Now, she is without insurance even as her mother is an essential worker.

Estimating the number of people who lack insurance is a complicated task. America’s fragmented health system lacks a single metric for how many people are shut out. Some researchers believe insurance losses will be low relative to job losses, because many lacked insurance despite working.

“The American healthcare financing system was not built to withstand the combined impact of a pandemic and a recession,” said Dr Adam Gaffney, the president of Physicians for a National Health Program. PNHP advocates for a single-payer health system in the US, similar to the NHS. “It’s inevitable that people will die because they can’t get the care they need, because of the looming recession.”

'The Free Market Is Working,' Declares For-Profit Health Industry Front Group. No, Say Medicare for All Advocates, 'It Is Not.'

"It is not doing a good job. Never has. Never will."

While the ravages of the coronavirus pandemic have only intensified

calls to do away with the costly and deadly for-profit health insurance

industry in the United States, the corporate-backed Partnership for

America's Health Care Future, an industry lobby group formed in 2018 to

combat Medicare for All, wants people to believe that the so-called

"free market" is doing just fine to take care of people's needs amid the

outbreak.

After the lobby group shared such a message on social media Sunday, however, Students for a National Health Program (SNaHP), a membership organization made up of medical school students and which advocates for Medicare for All, took issue and responded.

As part of it's industry-backed PR push, the lobby group—also know by its acronym P4AHCF—claimed that it public-private partnerships and innovative programs are filling "the gaps Medicare and Medicaid can't."

On Monday, P4AHCF declared in a separate tweet that its "members are #WorkingTogether to strengthen the employer-provided coverage more than 180 million Americans rely on." That message arrived on the heels of a new analysis published last week that showed an estimated 43 million Americans could lose their employer-provided health insurance this year as the economic downturn triggered by Covid-19 has skyrocketed unemployment to levels not seen since the Great Depression.

As Common Dreams reported Sunday, the report by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and the Urban Institute is just the latest to illustrate the failures of an health system that ties coverage to employment. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), the nation's most high-profile and backer of Medicare for All, has made this argument repeatedly:

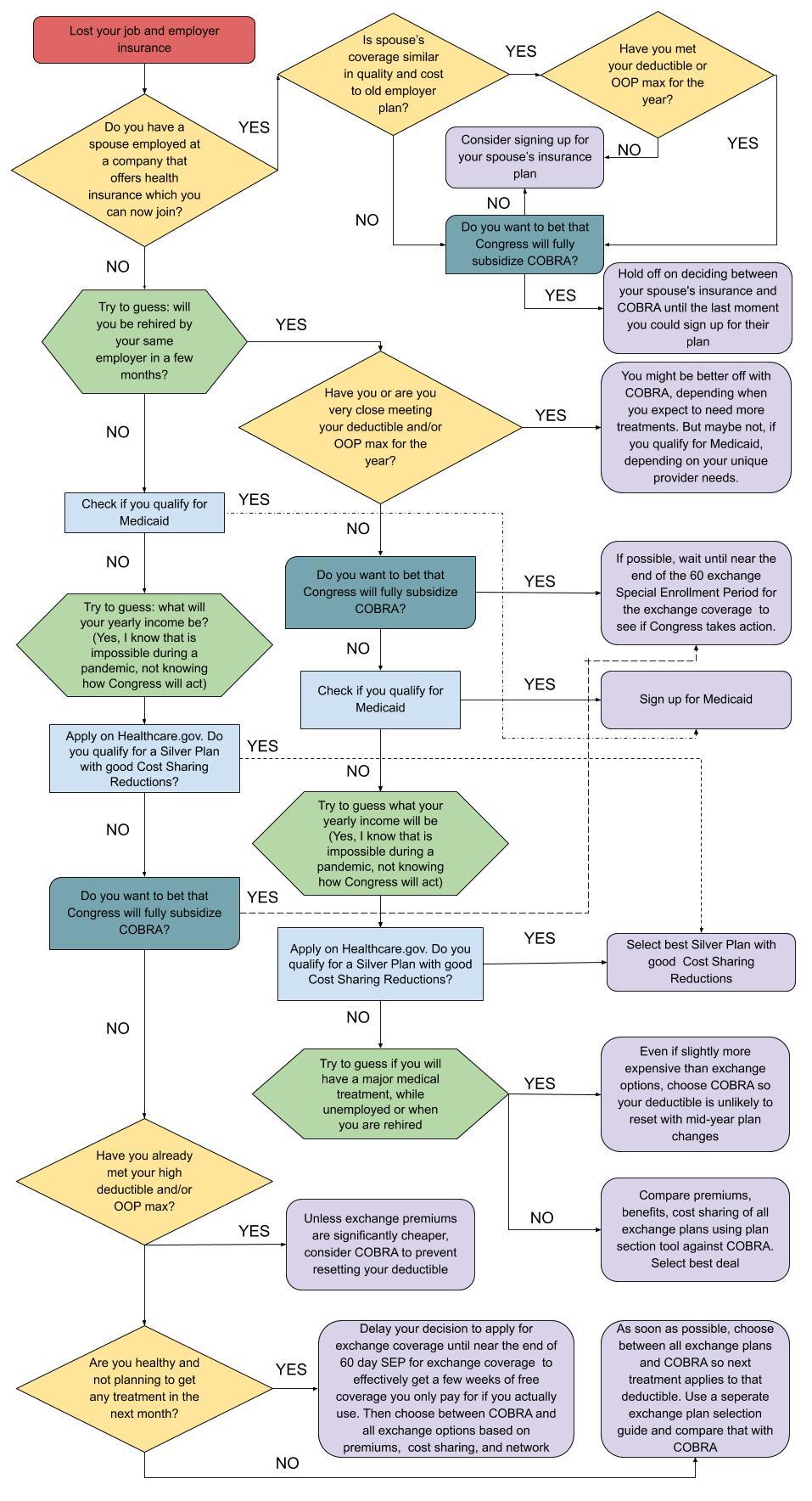

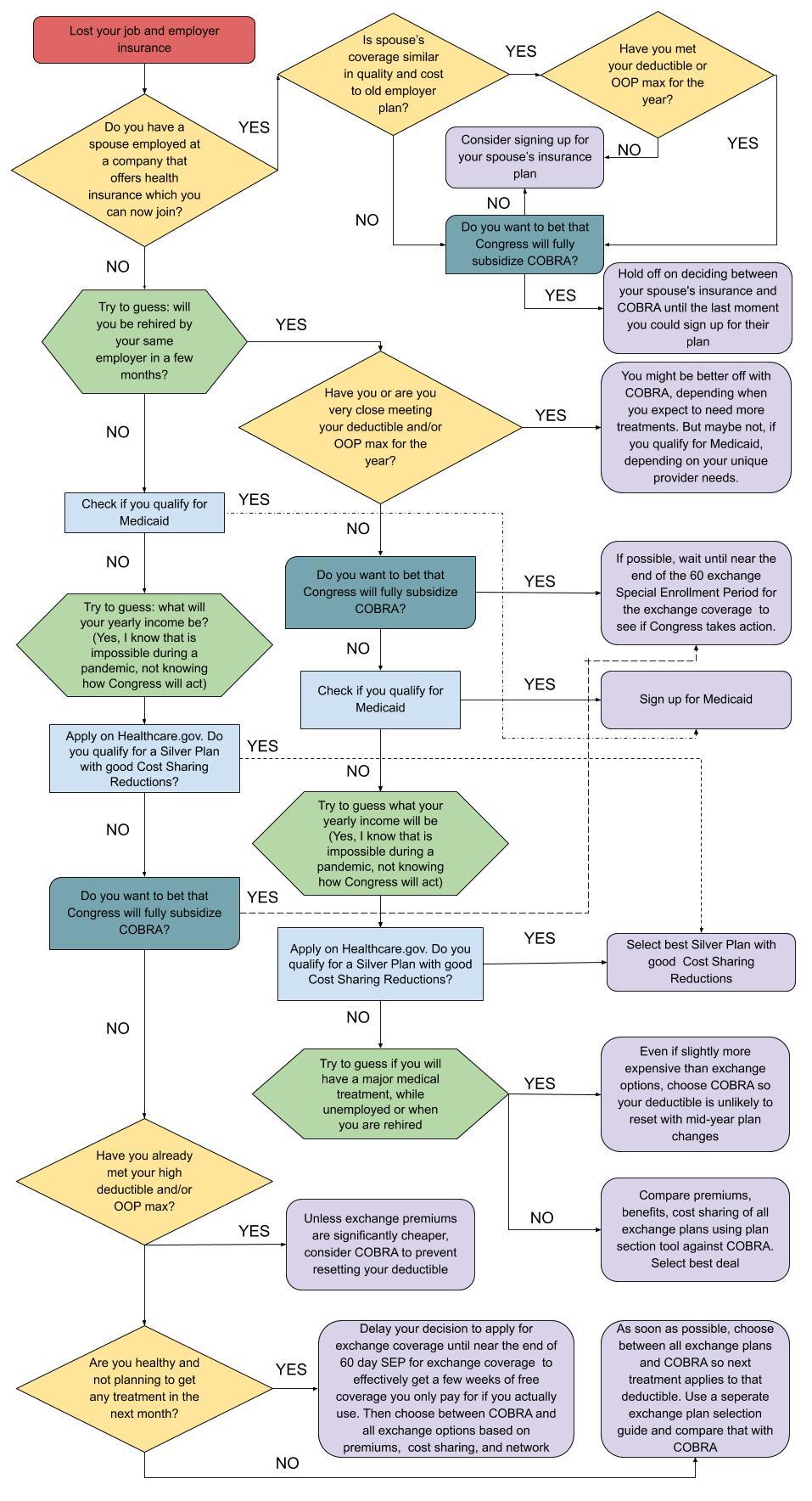

On Monday, journalist Jon Walker published a new piece for The American Prospect titled, "A Guide to the Nightmare of Getting Health Insurance in a Pandemic," which detailed the absurdity of the U.S. system.

Walker paints a picture of a healthcare system that is decidedly "not working" for those who need it most.

"Losing your health insurance when you lose your job is confusing in the best of times and even more so during the coronavirus crisis," Walker writes. "In addition to needing to deal with all the inherent complexities of our system, there are now numerous additional economic, political, and health factors that make it very difficult to know what is financially the best choice."

So is the so-called "free market" working?

Did it ever?

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2020/05/11/free-market-working-declares-profit-health-industry-front-group-no-say-medicare-all?cd-origin=rss&utm_term=AO&utm_campaign=Daily%20Newsletter&utm_content=email&utm_source=Daily%20Newsletter&utm_medium=Email

After the lobby group shared such a message on social media Sunday, however, Students for a National Health Program (SNaHP), a membership organization made up of medical school students and which advocates for Medicare for All, took issue and responded.

On Monday, P4AHCF declared in a separate tweet that its "members are #WorkingTogether to strengthen the employer-provided coverage more than 180 million Americans rely on." That message arrived on the heels of a new analysis published last week that showed an estimated 43 million Americans could lose their employer-provided health insurance this year as the economic downturn triggered by Covid-19 has skyrocketed unemployment to levels not seen since the Great Depression.

As Common Dreams reported Sunday, the report by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and the Urban Institute is just the latest to illustrate the failures of an health system that ties coverage to employment. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), the nation's most high-profile and backer of Medicare for All, has made this argument repeatedly:

"Losing your health insurance when you lose your job is confusing in the best of times and even more so during the coronavirus crisis," Walker writes. "In addition to needing to deal with all the inherent complexities of our system, there are now numerous additional economic, political, and health factors that make it very difficult to know what is financially the best choice."

So is the so-called "free market" working?

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2020/05/11/free-market-working-declares-profit-health-industry-front-group-no-say-medicare-all?cd-origin=rss&utm_term=AO&utm_campaign=Daily%20Newsletter&utm_content=email&utm_source=Daily%20Newsletter&utm_medium=Email

Covid-19: nursing homes account for 'staggering' share of US deaths, data show

Yale professor describes as ‘staggering’ research that reveals more

than half of all deaths in 14 US states from elderly care facilities

by Jessica Glernza - Common Dreams - May 11, 2020

Residents of nursing homes have accounted for a staggering proportion

of Covid-19 deaths in the US, according to incomplete data gathered by

healthcare researchers.

Privately compiled data shows such deaths now account for more than half of all fatalities in 14 states, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Only 33 states report nursing home-related deaths.

“I was on a phone call last week, where four or five patients came into our hospital just in one day from nursing homes,” said infectious disease specialist Dr Sunil Parikh, of Yale School of Public Health in Connecticut. “It’s just a staggering number day to day.”

Despite early warnings that nursing homes were vulnerable to Covid-19, because of group living settings and the age of residents, the federal government is only beginning to gather national data.

In Connecticut, 194 of 216 nursing homes have had at least one Covid-19 case. Nearly half the Covid-19 deaths in the state – more than 1,200 people – have been of nursing home residents. The proportion is higher elsewhere. In New Hampshire, 72% of deaths have been nursing home residents.

Parikh said limited testing and a lack of personal protective equipment such as masks hampered efforts to curb the spread of Covid-19 in care homes. Due to limited testing capacity, most state nursing homes are still only able to test residents with symptoms, even though the disease is known to spread asymptomatically.

“What I would like to see is the ability to test the entire nursing homes,” Parikh said. “This symptomatic approach is just not cutting it. Many states, including Connecticut, are starting to move in that direction … but I hope it becomes a national effort.”

Nursing homes have been closed to the public for weeks but a bleak picture has nonetheless emerged. In New Jersey, Governor Phil Murphy called in 120 members of the state national guard to help long-term care facilities, after 17 bodies piled up in one nursing home.

In Maine, a 72-year-old woman who went into a home to recover from surgery died just a few months later, in the state’s largest outbreak.

“I feel like I failed my mom because I put her in the wrong nursing home,” the woman’s daughter, Andrea Donovan, told the Bangor Daily News. “This facility is responsible for so much sadness for this family for not protecting their residents.”

Fifteen states have moved to shield nursing homes from lawsuits, according to Modern Healthcare.

Nursing home residents were among the first known cases of Covid-19 in the US. In mid-February in suburban Kirkland, Washington, 80 of 130 residents in one facility were sickened by an unknown respiratory illness, later identified as Covid-19.

Statistics from Kirkland now appear to tell the national story. Of 129 staff members, visitors and residents who got sick, all but one of the 22 who died were older residents, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

By early March, most Covid-19 deaths in the US could still be traced to Kirkland.

“One thing stands out as the virus spreads throughout the United States: nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are ground zero,” wrote Dr Tom Frieden, the former head of the CDC, for CNN on 8 March.

That day, Frieden called on federal authorities to ban visitors from nursing homes. US authorities announced new measures to protect residents several days later.

The CDC investigation into Kirkland was released on 18 March. It contained another warning: “Substantial morbidity and mortality might be averted if all long-term care facilities take steps now to prevent exposure of their residents to Covid-19.”

It was not until 19 April that the head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services promised to track all deaths in nursing homes. That requirement went into effect this Friday, but there is still a two-week grace period for compliance. During the period from 19 April to 8 May, 13,000 people died, according to an NBC News analysis.

“This is really decimating state after state,” said Parikh. “We have to have a very rapid shift [of focus] to the nursing homes, the veteran homes … Covid will be with us for many months.”

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/11/nursing-homes-us-data-coronavirus

Privately compiled data shows such deaths now account for more than half of all fatalities in 14 states, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Only 33 states report nursing home-related deaths.

“I was on a phone call last week, where four or five patients came into our hospital just in one day from nursing homes,” said infectious disease specialist Dr Sunil Parikh, of Yale School of Public Health in Connecticut. “It’s just a staggering number day to day.”

Despite early warnings that nursing homes were vulnerable to Covid-19, because of group living settings and the age of residents, the federal government is only beginning to gather national data.

In Connecticut, 194 of 216 nursing homes have had at least one Covid-19 case. Nearly half the Covid-19 deaths in the state – more than 1,200 people – have been of nursing home residents. The proportion is higher elsewhere. In New Hampshire, 72% of deaths have been nursing home residents.

Parikh said limited testing and a lack of personal protective equipment such as masks hampered efforts to curb the spread of Covid-19 in care homes. Due to limited testing capacity, most state nursing homes are still only able to test residents with symptoms, even though the disease is known to spread asymptomatically.

“What I would like to see is the ability to test the entire nursing homes,” Parikh said. “This symptomatic approach is just not cutting it. Many states, including Connecticut, are starting to move in that direction … but I hope it becomes a national effort.”

Nursing homes have been closed to the public for weeks but a bleak picture has nonetheless emerged. In New Jersey, Governor Phil Murphy called in 120 members of the state national guard to help long-term care facilities, after 17 bodies piled up in one nursing home.

In Maine, a 72-year-old woman who went into a home to recover from surgery died just a few months later, in the state’s largest outbreak.

“I feel like I failed my mom because I put her in the wrong nursing home,” the woman’s daughter, Andrea Donovan, told the Bangor Daily News. “This facility is responsible for so much sadness for this family for not protecting their residents.”

Fifteen states have moved to shield nursing homes from lawsuits, according to Modern Healthcare.

Nursing home residents were among the first known cases of Covid-19 in the US. In mid-February in suburban Kirkland, Washington, 80 of 130 residents in one facility were sickened by an unknown respiratory illness, later identified as Covid-19.

Statistics from Kirkland now appear to tell the national story. Of 129 staff members, visitors and residents who got sick, all but one of the 22 who died were older residents, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

By early March, most Covid-19 deaths in the US could still be traced to Kirkland.

“One thing stands out as the virus spreads throughout the United States: nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are ground zero,” wrote Dr Tom Frieden, the former head of the CDC, for CNN on 8 March.

That day, Frieden called on federal authorities to ban visitors from nursing homes. US authorities announced new measures to protect residents several days later.

The CDC investigation into Kirkland was released on 18 March. It contained another warning: “Substantial morbidity and mortality might be averted if all long-term care facilities take steps now to prevent exposure of their residents to Covid-19.”

It was not until 19 April that the head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services promised to track all deaths in nursing homes. That requirement went into effect this Friday, but there is still a two-week grace period for compliance. During the period from 19 April to 8 May, 13,000 people died, according to an NBC News analysis.

“This is really decimating state after state,” said Parikh. “We have to have a very rapid shift [of focus] to the nursing homes, the veteran homes … Covid will be with us for many months.”

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/11/nursing-homes-us-data-coronavirus

MaineHealth program helps jobless Mainers find health care and insurance

by J. Craig Anderson - Portland Press Herald - May 11, 2020

The health care system said it can connect patients with a range of options during the coronavirus pandemic.

This story and all coronavirus stories are free to the public. Please support us as we do our part to keep the community safe and informed.

With thousands of Mainers losing jobs and employer-sponsored health insurance during the coronavirus outbreak, leaders of a program at MaineHealth said help is available to obtain new coverage and find affordable options for care.

The healthcare system said Monday in a news release that it can connect patients with a range of options amid the economic turmoil brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

The MaineHealth Access to Care Team assists patients in getting coverage and care, it said. With nearly 125,000 Mainers out of work because of the COVID-19 pandemic, program leaders say can support those whose health care coverage has been impacted.

“Not all Mainers and patients in MaineHealth’s service area are aware of the variety of programs we offer to assist with access to healthcare resources,” said Kimberly Beaudoin, Access to Care Coverage Team director, in the release. “We want to let them know that we’re here to help.”

The help line for the Access to Care team is 833-644-3571. There is no charge to use the help line, which is funded by MaineHealth. Those calling are screened for all state and federal programs, and supported through the application process with the goal of ensuring access to comprehensive, affordable health care, MaineHealth said.

Access to Care also provides uninsured Mainers and those who do not qualify for public and private health insurance access to coverage case managers to help identify applicable programs, it said. In addition to offering options related to insurance, the program assists with low-cost or free prescription drug programs, donated health care services, connections to transportation, services for those experiencing homelessness and addresses other needs such as food insecurity, heating assistance and more.

“This program is in keeping with our vision working together so our communities are the healthiest in America,” said MaineHealth CEO Bill Caron in the release. “Access to Care works to ensure comprehensive, affordable health care and improve the quality of life. In these uncertain and trying times, we want anyone in need of support to reach out to us so that we can help.”

https://www.pressherald.com/2020/05/11/mainehealth-program-aims-to-keep-jobless-mainers-covered-by-health-insurance/E

Editor's Note -

I included the article about about Maine Health's efforts to help uninsured Patients' find health care coverage during the current period of the loss of employment-based health coverage. Unfortunately, the top leadership at Maine Health has consistently opposed the implementation of a universal healthcare program in Maine - a permanent solution to the existence of lack of health insurance in Maine.

-SPC

This story and all coronavirus stories are free to the public. Please support us as we do our part to keep the community safe and informed.

With thousands of Mainers losing jobs and employer-sponsored health insurance during the coronavirus outbreak, leaders of a program at MaineHealth said help is available to obtain new coverage and find affordable options for care.

The healthcare system said Monday in a news release that it can connect patients with a range of options amid the economic turmoil brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

The MaineHealth Access to Care Team assists patients in getting coverage and care, it said. With nearly 125,000 Mainers out of work because of the COVID-19 pandemic, program leaders say can support those whose health care coverage has been impacted.

“Not all Mainers and patients in MaineHealth’s service area are aware of the variety of programs we offer to assist with access to healthcare resources,” said Kimberly Beaudoin, Access to Care Coverage Team director, in the release. “We want to let them know that we’re here to help.”

The help line for the Access to Care team is 833-644-3571. There is no charge to use the help line, which is funded by MaineHealth. Those calling are screened for all state and federal programs, and supported through the application process with the goal of ensuring access to comprehensive, affordable health care, MaineHealth said.

Access to Care also provides uninsured Mainers and those who do not qualify for public and private health insurance access to coverage case managers to help identify applicable programs, it said. In addition to offering options related to insurance, the program assists with low-cost or free prescription drug programs, donated health care services, connections to transportation, services for those experiencing homelessness and addresses other needs such as food insecurity, heating assistance and more.

“This program is in keeping with our vision working together so our communities are the healthiest in America,” said MaineHealth CEO Bill Caron in the release. “Access to Care works to ensure comprehensive, affordable health care and improve the quality of life. In these uncertain and trying times, we want anyone in need of support to reach out to us so that we can help.”

https://www.pressherald.com/2020/05/11/mainehealth-program-aims-to-keep-jobless-mainers-covered-by-health-insurance/E

Editor's Note -

I included the article about about Maine Health's efforts to help uninsured Patients' find health care coverage during the current period of the loss of employment-based health coverage. Unfortunately, the top leadership at Maine Health has consistently opposed the implementation of a universal healthcare program in Maine - a permanent solution to the existence of lack of health insurance in Maine.

-SPC

As Hospitals Lose Revenue, More Than A Million Health Care Workers Lose Jobs

Laila Fetal - NPR - May 8, 2020

Michelle Sweeney could barely sleep. The nurse in Plymouth, Mass.,

had just learned she would be furloughed. She only had four hours the

next day to call all of her patients.

"I was in a panic state. I was sick over it," Sweeney said. "Our patients are the frailest, sickest group."

Sweeney works for Atrius Health as a case manager for patients with chronic health conditions and those who have been discharged from the hospital or emergency room.

"It's very devaluing, like a slap in the face," Sweeney said. "Nursing is who you are ... I've never been unemployed my entire life."

It's an ironic twist as the coronavirus pandemic sweeps the nation: The very workers tasked with treating those afflicted with the virus are losing work in droves. Emergency room visits are down. Non-urgent surgical procedures have largely been put on hold. Health care spending fell 18% in the first three months of the year. And 1.4 million health care workers lost their jobs in April, a sharp increase from the 42,000 reported in March, according to the Labor Department. Nearly 135,000 of the April losses were in hospitals.

Fae-Marie Donathan was among those who filed for unemployment in April. A nurse for 42 years, she worked until recently as a per diem nurse in the Surgical ICU at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. As the pandemic took hold in the U.S., Donathan, 64, expected her skills to be essential, but was recently told she would no longer be scheduled.

"I was thinking maybe I would have to worry about when I was going to get a day off," Donathan says. "I was thinking totally the opposite, never ever suspecting that I would be sitting at home not getting any hours at work."

Donathan says she normally makes around $1,100 every two weeks; she says her last paycheck was $46 in take-home pay. Asked for comment, a spokesperson for the University of Cincinnati Medical Center said in an email that the health system, "like many others, has experienced financial challenges as a result of the pandemic and has taken steps to align staffing with current needs as we seek to avoid layoffs."

The University of Cincinnati Medical Center is among many: The American Hospital Association recently predicted that U.S. hospitals and health systems would end up taking a $200 billion hit over a four-month period through June. Most of that money — $160 billion — is from lost revenue from more lucrative elective procedures.

"The only people who are coming into the hospitals are COVID-19 patients and emergencies," says American Hospital Association Executive Vice President Tom Nickels. "All of the so-called elective surgery, hips and knees and cardiac, etcetera, are no longer being done in most institutions around the country."

Nickels says hospitals are in a tight spot: "They're still having to have their institutions open. They are still caring for people who come in. They are still taking care of COVID-19. But that's an enormous amount of lost revenue."

The revenue losses will more severely affect poorer and more rural hospitals whose finances may be marginal in the best of times, Nickels says.

"That is certainly an existential threat," he says. "And I think [it] will threaten the ability of some of these hospitals to remain open."

Some nurses have traveled across the country to hot spots like New York City to find work, unsure if they'll have a job when they return home. But even there, hospitals that were once swamped are finally coming up for air and administrators are now reckoning with the financial impact of the pandemic.

Rozetta Ludwigsen, 64, works at a small hospital in Anacortes, Wash. She's gone from working a 40-hour week to only a few days a month.

"I never thought we'd be in this situation where there'd be no work for us," she said.

Before the pandemic, Ludwigsen was hoping to retire within the coming year. Now she may have to delay her plans for a year or longer.

In eastern Washington state, Shawn Reed, an ER nurse at MultiCare Valley Hospital, said she is sacrificing her own hours for people who need the money more.

"When I look at a nurse ... who's pregnant with her third child and I know she's going to need hours now, I am willing to fall on that sword," Reed said. "I can do it here and there, but I certainly can't do it long term."

The Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) has created a relief fund for its members who are struggling financially. Hundreds of their members have already applied for help.

"Looking at it from a long-term perspective, you have to worry about the profession and what's the impact on the profession," said Mike Hastings, the president of ENA.

A question of funding

The federal government has been distributing a portion of the $100 billion Provider Relief Fund to hospitals and other providers, as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Among the funding is a $10 billion allocation each for rural hospitals and pandemic hot spots.

Nickels, of the AHA, says it's too early to tell the effect of emergency federal funding targeted for hospitals, and whether those funds will help hospitals retain workers.

But Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, which is also the nation's second-largest nurses' union, says it's clear the federal funding is far from enough. The union has identified at least 200 hospitals nationwide cutting worker hours, mostly in the form of furloughs, according to Weingarten.

Even as the pandemic tapers off in some places, hospital revenue losses will take time to correct, especially because hospitals may face a potential "payer mix" problem before Americans go back to work. Many people who lose their jobs will also lose employer-sponsored health insurance, and those private plans reimburse providers at much higher rates than publicly funded plans like Medicaid and Medicare.

The Economic Policy Institute estimates that nearly 13 million Americans have likely lost their employer-sponsored health insurance so far.

"Even if [patients] do go back to the hospital, they'll be paying a lot lower rate than they did when they had insurance through their employer," says Christopher Whaley, a policy researcher with the Rand Corporation.

Weingarten says this crisis is an opportunity to rethink how the American hospital system is funded.

"This particular issue about what do we do in terms of funding our hospitals is not an issue in Canada. It's not an issue in Great Britain," she says. "It's not an issue where there are better funding systems."

But short of reworking the entire finance system of American health care, Weingarten says individual hospitals could also make changes to avoid cutting hours.

"Instead of reduction of the workforce, there should be a reallocation of work," she says. "Thinking innovatively and resourcefully, health care workers should be cross-trained to work in areas of the hospital that are overloaded like ER or ICU. Displaced workers could be trained and paid to staff a robust trace-and-isolate program as society reopens."

"Where's the end?"

Without that reallocation, some nurses still in the hospitals are taking on extra tasks in their already grueling 12-hour shifts. They're mopping rooms, changing sheets, taking out the trash and arranging rides because the people who once did that are gone.

"We're kind of jack-of-all-trades at this point," said Amy Erb, a nurse at California Pacific Medical Center in the Bay Area in northern California and a California Nurses Association Board member. "We're being phlebotomists, drawing labs. We're being social workers. We're being psychologists."

Then there are the days she's had her hours cut, which makes her worry about the future. So far her hospital has worked to avoid layoffs.

One nurse in a Detroit-area hospital says all the extra hours she once worked have disappeared.

"Our job title expanded exponentially," she said. She spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing her job. The one thing she thought she had was job security. "Then the layoffs started coming and I was like 'never mind.' "

She now often cleans the rooms and answers phones because the staff who did that are gone.

The financial stresses are compounded by an already stressful and terrifying time for healthcare workers.

"People were dying left and right," she said. "The way we were treating them then is different than now, maybe they would still be alive if they came in today ... it eats me up at night."

She spent the first month of the pandemic crying every night.

Her unit is a COVID-19 positive unit. Things are easing up now, but she still works with those COVID-19 patients every day. She's less afraid, she spends more time in the patient's rooms. She is their support system, their link to their families and their nurse.

Last week, Palomar Health in north San Diego County in California eliminated over 300 positions. But the workload didn't change — it just shifted to people like Sue Phillips, a critical care trauma and rapid response nurse.

"We have very limited physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy and that's part of our care team, so that's now going to fall onto our end to be providing that care," she said. "It's uncharted territory. In my 25 years of nursing, I've never seen anything like this before."

When a patient came in recently with broken bones, the doctor couldn't turn to the orthopedic technicians. Those technicians had been laid off. So Phillips found herself putting traction on a hospital bed, a pulley system that slowly lifts and moves the broken body parts.

"I've never had to do that before," she said. "The operating room staff was bare-boned staff, so there weren't enough people to assist the physician in doing the surgery that day."

She said she was worried she'd make a mistake. Also gone is the lift team that used to help Phillips pick up and turn patients. All of this, she said, adds stress to her job.

Meanwhile, her family is afraid to be around her because of her work. She's staying away from her husband. On their 30th wedding anniversary Friday, they'll celebrate apart.

Phillips is tired.

"We've been doing this now for six weeks. Where's the end? When are things going to get a little bit back to normal?" she asked. "Now we've had these huge layoffs."

https://www.npr.org/2020/05/08/852435761/as-hospitals-lose-revenue-thousands-of-health-care-workers-face-furloughs-layoff

"I was in a panic state. I was sick over it," Sweeney said. "Our patients are the frailest, sickest group."

Sweeney works for Atrius Health as a case manager for patients with chronic health conditions and those who have been discharged from the hospital or emergency room.

"It's very devaluing, like a slap in the face," Sweeney said. "Nursing is who you are ... I've never been unemployed my entire life."

It's an ironic twist as the coronavirus pandemic sweeps the nation: The very workers tasked with treating those afflicted with the virus are losing work in droves. Emergency room visits are down. Non-urgent surgical procedures have largely been put on hold. Health care spending fell 18% in the first three months of the year. And 1.4 million health care workers lost their jobs in April, a sharp increase from the 42,000 reported in March, according to the Labor Department. Nearly 135,000 of the April losses were in hospitals.

Fae-Marie Donathan was among those who filed for unemployment in April. A nurse for 42 years, she worked until recently as a per diem nurse in the Surgical ICU at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. As the pandemic took hold in the U.S., Donathan, 64, expected her skills to be essential, but was recently told she would no longer be scheduled.

"I was thinking maybe I would have to worry about when I was going to get a day off," Donathan says. "I was thinking totally the opposite, never ever suspecting that I would be sitting at home not getting any hours at work."

Donathan says she normally makes around $1,100 every two weeks; she says her last paycheck was $46 in take-home pay. Asked for comment, a spokesperson for the University of Cincinnati Medical Center said in an email that the health system, "like many others, has experienced financial challenges as a result of the pandemic and has taken steps to align staffing with current needs as we seek to avoid layoffs."

The University of Cincinnati Medical Center is among many: The American Hospital Association recently predicted that U.S. hospitals and health systems would end up taking a $200 billion hit over a four-month period through June. Most of that money — $160 billion — is from lost revenue from more lucrative elective procedures.

"The only people who are coming into the hospitals are COVID-19 patients and emergencies," says American Hospital Association Executive Vice President Tom Nickels. "All of the so-called elective surgery, hips and knees and cardiac, etcetera, are no longer being done in most institutions around the country."

Nickels says hospitals are in a tight spot: "They're still having to have their institutions open. They are still caring for people who come in. They are still taking care of COVID-19. But that's an enormous amount of lost revenue."

The revenue losses will more severely affect poorer and more rural hospitals whose finances may be marginal in the best of times, Nickels says.

"That is certainly an existential threat," he says. "And I think [it] will threaten the ability of some of these hospitals to remain open."

Some nurses have traveled across the country to hot spots like New York City to find work, unsure if they'll have a job when they return home. But even there, hospitals that were once swamped are finally coming up for air and administrators are now reckoning with the financial impact of the pandemic.

Rozetta Ludwigsen, 64, works at a small hospital in Anacortes, Wash. She's gone from working a 40-hour week to only a few days a month.

"I never thought we'd be in this situation where there'd be no work for us," she said.

Before the pandemic, Ludwigsen was hoping to retire within the coming year. Now she may have to delay her plans for a year or longer.

In eastern Washington state, Shawn Reed, an ER nurse at MultiCare Valley Hospital, said she is sacrificing her own hours for people who need the money more.

"When I look at a nurse ... who's pregnant with her third child and I know she's going to need hours now, I am willing to fall on that sword," Reed said. "I can do it here and there, but I certainly can't do it long term."

The Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) has created a relief fund for its members who are struggling financially. Hundreds of their members have already applied for help.

"Looking at it from a long-term perspective, you have to worry about the profession and what's the impact on the profession," said Mike Hastings, the president of ENA.

A question of funding

The federal government has been distributing a portion of the $100 billion Provider Relief Fund to hospitals and other providers, as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Among the funding is a $10 billion allocation each for rural hospitals and pandemic hot spots.

Nickels, of the AHA, says it's too early to tell the effect of emergency federal funding targeted for hospitals, and whether those funds will help hospitals retain workers.

But Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, which is also the nation's second-largest nurses' union, says it's clear the federal funding is far from enough. The union has identified at least 200 hospitals nationwide cutting worker hours, mostly in the form of furloughs, according to Weingarten.

Even as the pandemic tapers off in some places, hospital revenue losses will take time to correct, especially because hospitals may face a potential "payer mix" problem before Americans go back to work. Many people who lose their jobs will also lose employer-sponsored health insurance, and those private plans reimburse providers at much higher rates than publicly funded plans like Medicaid and Medicare.

The Economic Policy Institute estimates that nearly 13 million Americans have likely lost their employer-sponsored health insurance so far.

"Even if [patients] do go back to the hospital, they'll be paying a lot lower rate than they did when they had insurance through their employer," says Christopher Whaley, a policy researcher with the Rand Corporation.

Weingarten says this crisis is an opportunity to rethink how the American hospital system is funded.

"This particular issue about what do we do in terms of funding our hospitals is not an issue in Canada. It's not an issue in Great Britain," she says. "It's not an issue where there are better funding systems."

But short of reworking the entire finance system of American health care, Weingarten says individual hospitals could also make changes to avoid cutting hours.

"Instead of reduction of the workforce, there should be a reallocation of work," she says. "Thinking innovatively and resourcefully, health care workers should be cross-trained to work in areas of the hospital that are overloaded like ER or ICU. Displaced workers could be trained and paid to staff a robust trace-and-isolate program as society reopens."

"Where's the end?"

Without that reallocation, some nurses still in the hospitals are taking on extra tasks in their already grueling 12-hour shifts. They're mopping rooms, changing sheets, taking out the trash and arranging rides because the people who once did that are gone.

"We're kind of jack-of-all-trades at this point," said Amy Erb, a nurse at California Pacific Medical Center in the Bay Area in northern California and a California Nurses Association Board member. "We're being phlebotomists, drawing labs. We're being social workers. We're being psychologists."

Then there are the days she's had her hours cut, which makes her worry about the future. So far her hospital has worked to avoid layoffs.

One nurse in a Detroit-area hospital says all the extra hours she once worked have disappeared.

"Our job title expanded exponentially," she said. She spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing her job. The one thing she thought she had was job security. "Then the layoffs started coming and I was like 'never mind.' "

She now often cleans the rooms and answers phones because the staff who did that are gone.

The financial stresses are compounded by an already stressful and terrifying time for healthcare workers.

"People were dying left and right," she said. "The way we were treating them then is different than now, maybe they would still be alive if they came in today ... it eats me up at night."

She spent the first month of the pandemic crying every night.

Her unit is a COVID-19 positive unit. Things are easing up now, but she still works with those COVID-19 patients every day. She's less afraid, she spends more time in the patient's rooms. She is their support system, their link to their families and their nurse.

Last week, Palomar Health in north San Diego County in California eliminated over 300 positions. But the workload didn't change — it just shifted to people like Sue Phillips, a critical care trauma and rapid response nurse.

"We have very limited physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy and that's part of our care team, so that's now going to fall onto our end to be providing that care," she said. "It's uncharted territory. In my 25 years of nursing, I've never seen anything like this before."

When a patient came in recently with broken bones, the doctor couldn't turn to the orthopedic technicians. Those technicians had been laid off. So Phillips found herself putting traction on a hospital bed, a pulley system that slowly lifts and moves the broken body parts.

"I've never had to do that before," she said. "The operating room staff was bare-boned staff, so there weren't enough people to assist the physician in doing the surgery that day."

She said she was worried she'd make a mistake. Also gone is the lift team that used to help Phillips pick up and turn patients. All of this, she said, adds stress to her job.

Meanwhile, her family is afraid to be around her because of her work. She's staying away from her husband. On their 30th wedding anniversary Friday, they'll celebrate apart.

Phillips is tired.

"We've been doing this now for six weeks. Where's the end? When are things going to get a little bit back to normal?" she asked. "Now we've had these huge layoffs."

https://www.npr.org/2020/05/08/852435761/as-hospitals-lose-revenue-thousands-of-health-care-workers-face-furloughs-layoff

No comments:

Post a Comment