Do Physicians Trust Physicians to Make Medical Decisions?

by Milton Packer - MedPage - July 11, 2018

Decades ago, physicians were among the most trusted members of their communities. Clinicians were viewed along with the clergy as venerable sources of knowledge, life experience and comfort. Much like religious vocations, careers in medicine were regarded as a calling. Physicians routinely cared for the poor without asking for remuneration, subsiding their endeavors with fees collected from those who could afford to pay. We spent countless hours relentlessly pursuing a diagnosis, partnering with patients to wage a war on death, and communing with families. We were routinely invited to our patients' weddings and funerals.

Physicians were not excessively paid, but they were showered with respect and received preferential treatment in countless ways. (Remember MD license plates?) Physicians were commonly excused for minor traffic violations, simply because the police could imagine that they were in a hurry to see a patient. Most local jurisdictions granted physicians an exemption from jury duty, believing that they already provided an irreplaceable service to their communities. If you wanted reservations at short notice in a popular restaurant, you told them you were a doctor. Even physicians honored other physicians. Doctors who required medical care were given "professional courtesy." In the 1980s, I was a patient at the Mayo Clinic, and received incredible medical care for free; no one ever asked for insurance information, and I never received a bill. In truth, the tokens of respect were often trivial and elitist, and in most cases, no reasonable person should miss them. But their emblematic significance was unmistakable.

As Paul Starr wrote in his book The Social Transformation of American Medicine,physicians were accorded a respect usually given to astronauts and coaches of championship football teams. Society also granted physicians a virtual monopoly in all aspects of medical decision-making. Extraordinarily, 40-50 years ago, more than 75% of Americans had great confidence in medical leaders, according to Dhruv Khullar, MD, MPP, in the New York Times last January. Despite exceptionally long hours, physician burnout was virtually nonexistent.

In 2018, the days of universal respect for physicians are gone. Many patients now view practitioners as hurried and financially motivated, lacking empathy. No social courtesies are granted to physicians; on the contrary, physicians are generally viewed as being undeserving of elite perquisites. Laymen are suspicious of physician motivations. "Am I getting the treatment that is best for me or for my physician's pocketbook?" patients wonder. The decision-making authority of physicians has evaporated. Payers now tell physicians what they can prescribe, and healthcare systems remind physicians about the number of procedures they must perform to warrant their compensation.

In a Gallup poll taken last month, Americans were asked about their respect for many of society's institutions and organizations. Only 36% said that they had a great deal of trust in the medical system. The good news: The "medical system" fared better than public schools (29%), big business (25%), and the criminal justice system (22%). The bad news: we fared much worse than the military (74%) and the police (54%) -- worse even than the Presidency (37%).

The lack of trust in the medical system is a particular American phenomenon. The U.S. is tied for 24th place among 29 surveyed countries in a ranking of the proportion of adults who think that doctors can be trusted. Only 58% of U.S. adults trust physicians, as compared with 83% in Switzerland, 79% in Denmark, 78% in the Netherlands, and 76% in Britain. According to Khullar, just 25% of Americans feel confident about the health system -- a statistic even more dismal than the results of the Gallup poll.

Some physicians may believe that the lack of public trust is related to a lack of public understanding of the demands on the profession. Non-physicians cannot understand the magnitude of information, the rigorous requirements for technical expertise or the complexities of healthcare delivery. Only physicians can understand what it is like to be a physician.

Well, physicians certainly know what it feels like to be a physician AND a patient. So we should ask: When physicians need medical care, do physicians trust other doctors or the medical system to take care of them?

I cannot find any formal surveys on this question, but I am fairly confident that uncertainties about competence and motivations may be especially high -- amongst physicians!

Every week, I am asked by physicians who are wondering (and worrying) about the wisdom of medical advice or treatment that they or a family member has received. Why did they not take an adequate history? Why did they order tests that do not make any sense? Why did they recommend an elective procedure that had nothing to do with my chief complaint? When they found out I didn't need surgery, why did they stop caring for me? Why do they never respond to my phone calls or the questions I send by email? Do they really have the wisdom, experience and expertise to provide the best possible care?

It is true that many physicians no longer have the time or staff to communicate effectively -- even with their physician patients. But based on personal experience, they certainly have the staff to make countless telephone calls to chase $10-$25 copays.

Here is the good news: Physicians can rebuild trust. They can prioritize patient communication over revenues. They can take steps to make sure that patients are able to navigate the complex steps of healthcare.

But to do so, physicians would need to really want to. They would need to refocus their attention on patients rather than themselves.

Many readers who are physicians will certainly be inclined to dismiss my musings as old-fashioned and outdated, with little relevance to modern medicine. Most troubling, some may no longer even care if patients trust them.

Indeed, many physicians fully acquiesce in the decline in medicine as a trusted institution. For some, the practice of medicine is now a job, not a calling (and for some, not even a career). Many try to fill the emptiness in their souls with the knowledge that they are well-paid or that they perform more procedures than their colleagues. The achievement of numerical targets has replaced trust and respect as a source of personal gratification. Yet, soaring rates of physician burnout attest to the fact that this substitution is likely to be misguided and futile.

For some, the practice of medicine now resembles the board game Monopoly. Although popular, the game is also widely disliked. The game's goal is "grinding your opponents into dust," and cackling about it.

My father could not tolerate playing Monopoly. His reason: There is no honor, dignity, or fulfillment in playing or winning. Within the game's value system, a player succeeds without garnering another's trust, and there is no mechanism by which a player's choices can invoke respect. Under all circumstances, when the game ends, the person with the most money still loses.

Decades ago, physicians were among the most trusted members of their communities. Clinicians were viewed along with the clergy as venerable sources of knowledge, life experience and comfort. Much like religious vocations, careers in medicine were regarded as a calling. Physicians routinely cared for the poor without asking for remuneration, subsiding their endeavors with fees collected from those who could afford to pay. We spent countless hours relentlessly pursuing a diagnosis, partnering with patients to wage a war on death, and communing with families. We were routinely invited to our patients' weddings and funerals.

Physicians were not excessively paid, but they were showered with respect and received preferential treatment in countless ways. (Remember MD license plates?) Physicians were commonly excused for minor traffic violations, simply because the police could imagine that they were in a hurry to see a patient. Most local jurisdictions granted physicians an exemption from jury duty, believing that they already provided an irreplaceable service to their communities. If you wanted reservations at short notice in a popular restaurant, you told them you were a doctor. Even physicians honored other physicians. Doctors who required medical care were given "professional courtesy." In the 1980s, I was a patient at the Mayo Clinic, and received incredible medical care for free; no one ever asked for insurance information, and I never received a bill. In truth, the tokens of respect were often trivial and elitist, and in most cases, no reasonable person should miss them. But their emblematic significance was unmistakable.

As Paul Starr wrote in his book The Social Transformation of American Medicine,physicians were accorded a respect usually given to astronauts and coaches of championship football teams. Society also granted physicians a virtual monopoly in all aspects of medical decision-making. Extraordinarily, 40-50 years ago, more than 75% of Americans had great confidence in medical leaders, according to Dhruv Khullar, MD, MPP, in the New York Times last January. Despite exceptionally long hours, physician burnout was virtually nonexistent.

In 2018, the days of universal respect for physicians are gone. Many patients now view practitioners as hurried and financially motivated, lacking empathy. No social courtesies are granted to physicians; on the contrary, physicians are generally viewed as being undeserving of elite perquisites. Laymen are suspicious of physician motivations. "Am I getting the treatment that is best for me or for my physician's pocketbook?" patients wonder. The decision-making authority of physicians has evaporated. Payers now tell physicians what they can prescribe, and healthcare systems remind physicians about the number of procedures they must perform to warrant their compensation.

In a Gallup poll taken last month, Americans were asked about their respect for many of society's institutions and organizations. Only 36% said that they had a great deal of trust in the medical system. The good news: The "medical system" fared better than public schools (29%), big business (25%), and the criminal justice system (22%). The bad news: we fared much worse than the military (74%) and the police (54%) -- worse even than the Presidency (37%).

The lack of trust in the medical system is a particular American phenomenon. The U.S. is tied for 24th place among 29 surveyed countries in a ranking of the proportion of adults who think that doctors can be trusted. Only 58% of U.S. adults trust physicians, as compared with 83% in Switzerland, 79% in Denmark, 78% in the Netherlands, and 76% in Britain. According to Khullar, just 25% of Americans feel confident about the health system -- a statistic even more dismal than the results of the Gallup poll.

Some physicians may believe that the lack of public trust is related to a lack of public understanding of the demands on the profession. Non-physicians cannot understand the magnitude of information, the rigorous requirements for technical expertise or the complexities of healthcare delivery. Only physicians can understand what it is like to be a physician.

Well, physicians certainly know what it feels like to be a physician AND a patient. So we should ask: When physicians need medical care, do physicians trust other doctors or the medical system to take care of them?

I cannot find any formal surveys on this question, but I am fairly confident that uncertainties about competence and motivations may be especially high -- amongst physicians!

Every week, I am asked by physicians who are wondering (and worrying) about the wisdom of medical advice or treatment that they or a family member has received. Why did they not take an adequate history? Why did they order tests that do not make any sense? Why did they recommend an elective procedure that had nothing to do with my chief complaint? When they found out I didn't need surgery, why did they stop caring for me? Why do they never respond to my phone calls or the questions I send by email? Do they really have the wisdom, experience and expertise to provide the best possible care?

It is true that many physicians no longer have the time or staff to communicate effectively -- even with their physician patients. But based on personal experience, they certainly have the staff to make countless telephone calls to chase $10-$25 copays.

Here is the good news: Physicians can rebuild trust. They can prioritize patient communication over revenues. They can take steps to make sure that patients are able to navigate the complex steps of healthcare.

But to do so, physicians would need to really want to. They would need to refocus their attention on patients rather than themselves.

Many readers who are physicians will certainly be inclined to dismiss my musings as old-fashioned and outdated, with little relevance to modern medicine. Most troubling, some may no longer even care if patients trust them.

Indeed, many physicians fully acquiesce in the decline in medicine as a trusted institution. For some, the practice of medicine is now a job, not a calling (and for some, not even a career). Many try to fill the emptiness in their souls with the knowledge that they are well-paid or that they perform more procedures than their colleagues. The achievement of numerical targets has replaced trust and respect as a source of personal gratification. Yet, soaring rates of physician burnout attest to the fact that this substitution is likely to be misguided and futile.

For some, the practice of medicine now resembles the board game Monopoly. Although popular, the game is also widely disliked. The game's goal is "grinding your opponents into dust," and cackling about it.

My father could not tolerate playing Monopoly. His reason: There is no honor, dignity, or fulfillment in playing or winning. Within the game's value system, a player succeeds without garnering another's trust, and there is no mechanism by which a player's choices can invoke respect. Under all circumstances, when the game ends, the person with the most money still loses.

It’s 4 A.M. The Baby’s Coming. But the Hospital Is 100 Miles Away.

by Jack Healey - NYT - July 17, 2018

KENNETT, Mo. — A few hours after the only hospital in town shut its doors forever, Kela Abernathy bolted awake at 4:30 a.m., screaming in pain.

Oh God, she remembered thinking, it’s the twins.

They were not due for another two months. But the contractions seizing Ms. Abernathy’s lower back early that June morning told her that her son and daughter were coming. Now.

Ms. Abernathy, 21, staggered out of bed and yelled for her mother, Lynn, who had been lying awake on the living-room couch. They grabbed a few bags, scooped up Ms. Abernathy’s 2-year-old son and were soon hurtling across this poor patch of southeast Missouri in their Pontiac Bonneville, racing for help. The old hospital used to be around the corner. Now, her new doctor and hospital were nearly 100 miles away.

Medical help is growing dangerously distant for women in rural America. At least 85 rural hospitals — about 5 percent of the country’s total — have closed since 2010, and obstetric care has faced even starker cutbacks as rural hospitals calculate the hard math of survival, weighing the cost of providing 24/7 delivery services against dwindling birthrates, doctor and nursing shortages and falling revenues.

Today, researchers estimate that fewer than half of the country’s rural counties still have a hospital that offers obstetric care, an absence that adds to the obstacles rural women face in getting health care. Specialists are increasingly clustered in bigger cities. Clinics that provide abortions, long-term birth control and other reproductive services have been forced to close in many smaller towns.

“It’s scary,” said Katie Penn, who said she was rejected by eight doctors before finding an obstetrician in Jonesboro, Ark., about an hour from Kennett. “You never know what can happen.”

When obstetric services leave town, a cascade of risks follows, according to experts at the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center who have studied the consequences. Women go to fewer doctor’s appointments and more babies are born premature, compared with similar places that do not lose access to care. And when women go into labor, they are more likely to end up at emergency rooms with no obstetric care or to deliver outside a hospital altogether.

Families struggle to afford the gas, child care and time off work to drive hundreds of miles for an ultrasound, shots or hospital tests. Women say they have ended up on waiting lists at overwhelmed clinics, or been turned away because they said doctors did not want to take them as patients late into their pregnancies.

Women like Ms. Abernathy and Ms. Penn are particularly isolated because they live in the Missouri Bootheel in the southeast corner of the state, named for the way the area juts out of the state’s otherwise orderly shape.

The region was already coping with some of the state’s highest rates of maternal and infant mortality, and then in April came the news that Dunklin County’s only hospital, the Twin Rivers Regional Medical Center, would be closing. More than 179 rural counties have lost hospital obstetric care since 2004. Dunklin was now one of them.

‘Hospital Closed. Call 911 for Emergencies’

The white, 116-bed hospital had been a busy lifeline for this 31,000-person county’s most vulnerable people. The emergency room received about 22,000 visits a year, and unlike many struggling hospitals, the maternity ward was busy. About 400 babies were born at Twin Rivers every year, often to mothers who had themselves been born in the same rooms.

About 95 percent of the hospital’s patients were on Medicare, Medicaid or had no insurance, said Dr. Steve Pu, a former member of the hospital’s advisory board. Rural hospitals like Kennett’s are being financially battered by several factors: Cutsto public health-insurance programs, struggles with debt and sharply worsening finances in states that did not expand Medicaid.

In April, Twin Rivers announced it would be shutting down as part of a corporate consolidation by its owner, Community Health Systems, a publicly traded, for-profit hospital company. In a statement announcing the closing, the hospital’s local chief executive, Christian H. Jones, called it the “most sustainable plan for the future.”

Patients say they were told to seek care at another Community Health Systems hospital in Poplar Bluff, about 50 miles away down narrow two-lane roads. The hospital in Kennett had about 300 employees, the largest employer in a county with a 5.5 percent unemployment rate.

Then last month, with little warning, a sign went up at Twin Rivers: HOSPITAL CLOSED. CALL 911 FOR EMERGENCIES. Its last day of operations was June 11, more than two weeks earlier than the date executives initially told people in Kennett.

The only obstetrician in Kennett had operated his practice out of the hospital, and he began discharging patients and winding down services in the weeks before Twin Rivers closed. Women said his waiting room became a scene of sadness and confusion as they worried about where they would go next and how they would afford gas for weekly visits at distant hospitals when they barely had enough money to pay electric bills and rent.

The only pediatrician in Kennett, Andy Beach, hung a banner outside his clinic that mirrored the town’s defiant spirit, “We are not leaving the area!”

An ambulance service has been shuttling patients to other hospitals in the region, and a medical helicopter is on call for the worst emergencies. Doctors around Kennett and a hospital in Jonesboro are working to open urgent-care clinics, and officials have put a tax increase onto August ballots to raise money to build a hospital. Someday.

State officials and doctors are also trying to work out a plan and find $1.5 million to reopen the obstetric unit at the Pemiscot County hospital in Hayti, the closest hospital to Kennett.

In the meantime, the absence of local care is being felt already.

Mary Louisa, who was 26 weeks pregnant, recently started experiencing contractions that are a hallmark of preterm labor but had not had a full prenatal checkup in a month.

Susanna Hernandez’s first pregnancy ended in miscarriage. Now she was worried about her second and had not seen a doctor since the hospital in Kennett closed. Every few minutes, she touches her abdomen to feel for a kick, a movement, any sign that the girl inside is still healthy and growing. Ms. Hernandez, who emigrated from Mexico a year ago, speaks almost no English and spends her days trying to relax and pray.

“Our community is just in panic,” Deloris Johnson, who sits on the county’s ambulance board, said in an interview in June. “They don’t know what to do.”

Then, this month came the news that she and many in Kennett had been dreading. Two infant boys, each about a month old, died on opposite ends of the county, one on July 4 and the other the following morning.

In both instances, officials said that family members discovered the children unconscious and rushed them to local ambulance stations. One was driven 20 miles to a hospital in Paragould, Ark., and the other was taken to a hospital in Piggott, Ark., where they were each pronounced dead, investigators said. Investigators would not release the children’s names or any additional details. They said autopsy reports had not been completed and said they did not yet know how the children had died, or whether any intervention could have saved them.

Their deaths sent a shudder through Kennett.

“This is just the beginning,” Ms. Johnson said. “To think we don’t even have a damn hospital for these people to go to.”

Rushed Into Surgery

After a Four-Hour Trek

As Ms. Abernathy and her mother raced down dark country roads at 90 miles an hour, all they could think about were the twins. Would she have to deliver them on the side of the road, before she got to a hospital? Would the babies be O.K.?

They pulled into the town of Hayti 17 miles east and rushed into the Pemiscot County hospital. It was an act of desperation. The hospital’s obstetrics unit had closed four years ago, and the emergency-room staff looked shocked to see her. The labor and delivery rooms now sat unused.

The staff told Ms. Abernathy she needed to reach the hospital now caring for her after Kennett’s closed: St. Francis Medical Center in Cape Girardeau, Mo., nearly 80 miles away. It had a neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal operating rooms and a full battery of obstetric doctors and nurses. But there was no ambulance ready to take her.

Ms. Abernathy said she waited for about 25 minutes as an ambulance rushed over from Kennett to pick her up. An obstetric nurse rode along, rubbing her back and helping her breathe as the contractions continued.

When they passed through the small town of Sikeston, Ms. Abernathy said the ambulance driver asked whether they needed to stop at the hospital there. Keep going, Ms. Abernathy and the nurse told him. Nearly four hours after she woke up screaming in bed, they arrived at a hospital with an obstetrics ward.

Her doctor rushed to get her into surgery. Forty-five minutes later, the twins were born by cesarean section, first Kaleb at 3 pounds 6 ounces and then Kylynn at 2 pounds 12 ounces.

They were healthy, but because they arrived early, they would need weeks of close care at the hospital: nurses who could check their breathing and vital signs and also show Ms. Abernathy how the babies needed to be touched and held.

This meant that Ms. Abernathy had to make regular 200-mile round trips to the hospital to see the twins and then back to Kennett to be with her 2-year-old. One day, her C-section incision was so inflamed by the drive that she could barely stand. Another afternoon, she and her mother had to pull over when a summer storm swamped the highway.

Ms. Abernathy said she was eager to bring the twins home and to get back to her $8.50-an-hour job as a home health aide. There is rent to make, baby clothes to purchase, $80 of gas to buy for the coming week.

“My mom raised me to be independent,” she said. “I’ve always worked.”

One morning, she lay underneath a blanket on her couch, exhausted and upset about the inconveniences and indignities of the past month and the stress of not seeing a doctor for weeks when she knew she was a high-risk patient.

“I was an emotional wreck. I can’t tell you how many times I cried,” Ms. Abernathy said, as her mother hovered beside her. “We can’t keep a hospital. What is our community coming to?”

Editor's Note:

The preceding article is a dramatic example of the inevitable result of applying market principles to the delivery of health care.

Caveat Emptor!

-SPC

The real driver of health care spending

An inefficiency gap is boosting costs — and profits

Edward M. Murphy - Commonwealth Magazine - July 9, 2018

THE HEALTH CARE DEBATES that occurred in Washington over the past year were largely irrelevant to what’s happening in the health care marketplace. Republicans couldn’t repeal the Affordable Care Act but they made some changes that weakened it. Those changes will increase insurance premiums in the individual market but they do nothing to address the most significant trends that are evolving across the system. To understand the important trends, one must look elsewhere.

In March, three researchers from the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health published a study in JAMA analyzing the well-known reality that the United States spends dramatically more on health care than other wealthy countries. They compared the US, where health care consumes 17.8 per cent of gross domestic product, to 10 comparable nations where the mean expenditure is 11.5 percent. Despite spending much less, the other countries provide health insurance to their entire populations and have outcomes equal to or better than ours. The researchers found that this inefficiency gap is primarily driven by two characteristics of the US system: the high cost of pharmaceuticals and inordinate administrative expenses.

For example, annual per capita pharmaceutical expenditure in the US is $1,443 as compared to an average of $749 in the 10 other countries. Our administrative costs consume 8 percent of total spending as compared to a range of 1 to 3 percent elsewhere. No one else is close on either of these measures.

The high administrative spending derives in large part from the fact that 55 percent of the people in the US are covered by private health insurers who embed their own billing requirements, expenses, and profit into the system. The next highest country in this regard is Germany, where 10.8 percent of the population is covered by private insurers. In many countries, there are no such middlemen.

Coincidentally, when the JAMA study was published, the large publicly traded health care companies that dominate the US market had just finished disclosing their 2017 financial results. Examining those results provides additional insight into the economic forces that make our system so expensive and inefficient. The scale of the money involved is sometimes hard to grasp. The largest health care corporations, those included in the S&P 500, had almost $2 trillion in revenue last year. (Table 1)

Most of these enormous companies are engaged in one of two businesses: they’re either selling drugs or they’re selling health insurance. The excess costs reported by the Harvard researchers serve mainly to support the revenue of the companies in those fields.

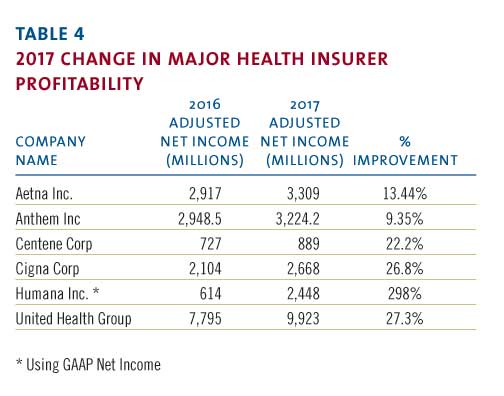

The 2017 reporting of corporate profits was complicated by the passage of the new tax bill. But most companies also reported “adjusted net income,” which shows their normalized profits after accounting for the one-time impact of the tax law. The chart below (Table 2) uses the adjusted numbers to show the largest annual profits among S&P health care companies.

Health insurers such as United Health and retailers such as CVS have enormous revenue and impressive profits but, when profit is measured as a percentage of revenue, they can’t compete with biotech and pharma. The highest relative profitability, using the same reported adjusted results, is in the chart below. (Table 3)

These profit margins show that there are many situations where between a third and a half of every dollar spent on a prescription drug falls to the bottom line of the of the company that made it. This profit derives in large part from the enormous difference in drug prices in the US versus other countries where such prices are more effectively controlled.

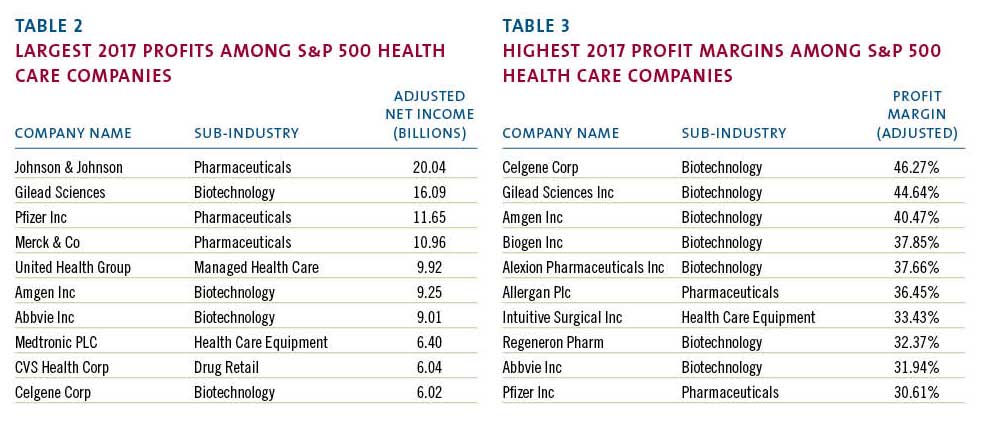

The high administrative cost of the US system stems from the large portion of the market dominated by insurance companies looking to maximize their profits. Notwithstanding many news stories about turmoil in the insurance markets, 2017 was a banner year for the largest health insurers. The big players all had significant increases in annual profitability in 2017.

Note that Humana did not report “adjusted” numbers even though its profit was swollen by unusual events. A major distortion was a huge break-up fee the company received from a failed merger. That accounted for approximately $630 million in after-tax profit. Even discounting that, it was a very good year.

The revenue and profitability of these corporations support the proposition that high pharmaceutical prices and insurance-related administrative costs account for much of the extraordinary expense of our system. US health policy, or the absence thereof, has enabled these businesses annually to drive costs up for the benefit of their bottom line. That effect will continue. Not surprisingly, the big health care companies are developing new strategies to enhance their businesses and drive their profits going forward.

The term now heard often among health care giants is “vertical integration,” which means combining upstream suppliers with downstream buyers to control the flow of business. If this strategy persists, health care delivery will evolve significantly although it is unlikely to become less expensive. The most prominent current example of vertical integration is the planned $68 billion acquisition of Aetna by CVS.

How would these companies work together? A Wall Street analyst recently described the vision as a way to “identify high risk patients and preemptively get them into a Minute Clinic.” Thus, your health insurer could send you to a local store for diagnosis, treatment, drugs, and anything else you might need from the shelves. This will keep even more of the health care dollar under their control.

Similarly, Cigna is in the process of acquiring Express Scripts, a huge pharmacy benefits manager, for $54 billion, another attempt to bring more services under one roof. The combined company would have annual revenue of $142 billion and, presumably, enough leverage with drug companies to improve profits although not necessarily to lower costs to patients. United Health, a leader of vertical integration, previously bought a pharmacy benefit manager but co-pays and deductibles for its patients have continued to climb. United has aggressively acquired physician practices in recent years and is now in the process of buying DaVita Medical Group, which operates nearly 300 clinics and outpatient surgical centers.

More striking are reports of a potential but unsigned merger of Walmart and Humana, a combined company that would have revenue of $550 billion. Walmart is a large operator of retail pharmacies inside its stores and the logic is similar to the Aetna-CVS deal. Humana, a huge insurer, is separately in the process of acquiring a large home health business from Kindred so this could represent yet another level of vertical integration.

If this course continues, the health care system will evolve quickly, giving fewer and larger companies even more market leverage. Integration of this kind benefits the large corporations that initiate it but there is no evidence it will lead to lower costs, improved access, or enhanced quality. These changes are driven by highly focused corporate financial interests and are occurring without reference to public policy. That’s because there is no coherent public policy to guide these changes.

On May 11, President Trump made a long-awaited speech to reveal what he described as “the most sweeping action in history to lower the price of prescription drugs for the American people.” His typically firebrand language struck at “drug makers, insurance companies, distributors, pharmacy benefit managers, and many others” who contributed to “this incredible abuse.” His attack seemed to target the large public companies that have benefited from the abuse. Unsurprisingly, his speech did not include specifics. His staff then released tepid policy details, which immediately generated a significant upward spike in the biotech stock index as well as the stock prices of other large health care companies. For all the presidential bombast, investors saw Trump’s policy for what it is: indifference to the current path and no threat to high prices.

It is not in the interest of huge profit-making corporations to restrain the overall cost of the US health care system. In fact, their interest is served by driving health care expenditures higher. When combined with the spending analysis provided by researchers, the financial data disclosed by public corporations point to a path that the country must follow to make our system more coherent and less costly. Any progress will require driving down pharmaceutical pricing and reducing administrative costs imposed by middlemen. We are not doing that yet but, ultimately, we must.

Hidden From View: The Astonishingly High Administrative Costs of U.S. Health Care

The complexity of the system comes with costs that aren’t obvious but that we all pay.

by Austin Frakt - NYT - July 16, 2018

It takes only a glance at a hospital bill or at the myriad choices you may have for health care coverage to get a sense of the bewildering complexity of health care financing in the United States. That complexity doesn’t just exact a cognitive cost. It also comes with administrative costs that are largely hidden from view but that we all pay.

Because they’re not directly related to patient care, we rarely think about administrative costs. They’re high.

A widely cited study published in The New England Journal of Medicine used data from 1999 to estimate that about 30 percent of American health care expenditures were the result of administration, about twice what it is in Canada. If the figures hold today, they mean that out of the average of about $19,000 that U.S. workers and their employers pay for family coverage each year, $5,700 goes toward administrative costs.

Such costs aren’t all bad. Some are tied up in things we may want, such as creating a quality improvement program. Others are for things we may dislike — for example, figuring out which of our claims to accept or reject or sending us bills. Others are just necessary, like processing payments; hiring and managing doctors and other employees; or maintaining information systems.

That New England Journal of Medicine study is still the only one on administrative costs that encompasses the entire health system. Many other more recent studies examine important portions of it, however. The story remains the same: Like the overall cost of the U.S. health system, its administrative cost alone is No. 1 in the world.

Using data from 2010 and 2011, one study, published in Health Affairs, compared hospital administrative costs in the United States with those in seven other places: Canada, England, Scotland, Wales, France, Germany and the Netherlands.

At just over 25 percent of total spending on hospital care (or 1.4 percent of total United States economic output), American hospital administrative costs exceed those of all the other places. The Netherlands was second in hospital administrative costs: almost 20 percent of hospital spending and 0.8 percent of that country’s G.D.P.

At the low end were Canada and Scotland, which both spend about 12 percent of hospital expenditures on administration, or about half a percent of G.D.P.

Hospitals are not the only source of high administrative spending in the United States. Physician practices also devote a large proportion of revenue to administration. By one estimate, for every 10 physicians providing care, almost seven additional people are engaged in billing-related activities.

It is no surprise then that a majority of American doctors say that generating bills and collecting payments is a major problem. Canadian practices spend only 27 percent of what U.S. ones do on dealing with payers like Medicare or private insurers.

Another study in Health Affairs surveyed physicians and physician practice administrators about billing tasks. It found that doctors spend about three hours per week dealing with billing-related matters. For each doctor, a further 19 hours per week are spent by medical support workers. And 36 hours per week of administrators’ time is consumed in this way. Added together, this time costs an additional $68,000 per year per physician (in 2006). Because these are administrative costs, that’s above and beyond the cost associated with direct provision of medical care.

In JAMA, scholars from Harvard and Duke examined the billing-related costs in an academic medical center. Their study essentially followed bills through the system to see how much time different types of medical workers spent in generating and processing them.

At the low end, such activities accounted for only 3 percent of revenue for surgical procedures, perhaps because surgery is itself so expensive. At the high end, 25 percent of emergency department visit revenue went toward billing costs. Primary care visits were in the middle, with billing functions accounting for 15 percent of revenue, or about $100,000 per year per primary care provider.

“The extraordinary costs we see are not because of administrative slack or because health care leaders don’t try to economize,” said Kevin Schulman, a co-author of the study and a professor of medicine at Duke. “The high administrative costs are functions of the system’s complexity.”

Costs related to billing appear to be growing. A literature review by Elsa Pearson, a policy analyst with the Boston University School of Public Health, found that in 2009 they accounted for about 14 percent of total health expenditures. By 2012, the figure was closer to 17 percent.

One obvious source of complexity of the American health system is its multiplicity of payers. A typical hospital has to contend not just with several public health programs, like Medicare and Medicaid, but also with many private insurers, each with its own set of procedures and forms (whether electronic or paper) for billing and collecting payment. By one estimate, 80 percent of the billing-related costs in the United States are because of contending with this added complexity.

“One can have choice without costly complexity,” said Barak Richman, a co-author of the JAMA study and a professor of law at Duke. “Switzerland and Germany, for example, have lower administrative costs than the U.S. but exhibit a robust choice of health insurers.”

An additional source of costs for health care providers is chasing patients for their portion of bills, the part not covered by insurance. With deductibles and co-payments on the rise, more patients are facing cost sharing that they may not be able to pay, possibly leading to rising costs for providers, or the collection agencies they work with, in trying to get them to do so.

Using data from Athenahealth, the Harvard health economist Michael Chernew computed the proportion of doctors’ bills that were paid by patients. For relatively small bills, those under $75, over 90 percent were paid within a year. For larger ones, over $200, that rate fell to 67 percent.

“It’s a mistake to think that billing issues only reflect complex interactions between providers and insurers,” Mr. Chernew said. “As patients are required to pay more money out of pocket, providers devote more resources to collecting it.”

A distinguishing feature of the American health system is that it offers a lot of choice, including among health plans. Because insurers and public programs have not coordinated on a set of standards for pricing, billing and collection — whatever the benefits of choice — one of the consequences is high administrative burden. And that’s another reason for high American health care prices.

HHS Plans to Delete 20 Years of Critical Medical Guidelines Next Week

by John Campbell - The Daily Beast - July 12, 2018

Experts say the database of carefully curated medical guidelines is one of a kind, used constantly by medical professionals, and on July 16 will ‘go dark’ due to budget cuts.

The Trump Administration is planning to eliminate a vast trove of medical guidelines that for nearly 20 years has been a critical resource for doctors, researchers and others in the medical community.

Maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], part of the Department of Health and Human Services, the database is known as the National Guideline Clearinghouse [NGC], and it’s scheduled to “go dark,” in the words of an official there, on July 16.

Medical guidelines like those compiled by AHRQ aren’t something laypeople spend much time thinking about, but experts like Valerie King, a professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Director of Research at the Center for Evidence-based Policy at Oregon Health & Science University, said the NGC is perhaps the most important repository of evidence-based research available.

“Guideline.gov was our go-to source, and there is nothing else like it in the world,” King said, referring to the URL at which the database is hosted, which the agency says receives about 200,000 visitors per month. “It is a singular resource,” King added.

Medical guidelines are best thought of as cheatsheets for the medical field, compiling the latest research in an easy-to use format. When doctors want to know when they should start insulin treatments, or how best to manage an HIV patient in unstable housing — even something as mundane as when to start an older patient on a vitamin D supplement — they look for the relevant guidelines. The documents are published by a myriad of professional and other organizations, and NGC has long been considered among the most comprehensive and reliable repositories in the world.

AHRQ said it’s looking for a partner that can carry on the work of NGC, but that effort hasn’t panned out yet.

“AHRQ agrees that guidelines play an important role in clinical decision making, but hard decisions had to be made about how to use the resources at our disposal,” said AHRQ spokesperson Alison Hunt in an email. The operating budget for the NGC last year was $1.2 million, Hunt said, and reductions in funding forced the agency’s hand.

Not even an archived version of the site will remain, according to an official at AHRQ. A report from the Sunlight Foundation’s Web Integrity Project found the agency announced the site’s retirement, as well as that of a related but less trafficked “Quality Measures” site, this Spring. Some of the NGC’s pages are preserved in a third party archive, but no comprehensive backup of the site’s contents or search functions exists.

Part of what makes NGC unique is its breadth, King explained. Drawing on research from all over the country and the world, from professional organizations and research institutes, the site offers a free, and virtually comprehensive, body of guidelines in a centralized and easily searchable location. Rather than seeking out guidelines from dozens of individual publishers, King said, the NGC allows researchers to find the full range of resources in one stop.

The site plays another critical role, King said: that of gatekeeper. Because medical guidelines are produced by such a vast array of organizations, they vary widely in quality.

“In times past, there were an awful lot of, let me put air quotes around this — ‘guidelines’ — that weren’t of good methodologic quality,” King said. “They were typically just expert opinions, or what we jokingly refer to as BOGSAT guidelines: ‘bunch of guys sitting around a table’ guidelines.”

The NGC has a screening process designed to keep weakly supported research out. It also offers summaries of research and an interactive, searchable interface.

That gatekeeping role has sometimes made AHRQ a target. The agency was nearly eliminated shortly after its establishment, in the mid-90s, when it endorsed non-surgical interventions for back pain, a position that angered the North American Spine Society, a trade group representing spine surgeons. A subsequent campaign led to significant funding losses for AHRQ, and since then, the agency as a whole has been a perennial target for Republicans who have argued that its work is duplicated at other federal agencies.

The vetting role played by the NGC is a critical one, says Roy Poses, with the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

“Many guidelines are actually written mainly for commercial purposes or public relations purposes,” said Poses, and can be subtly shaped to promote a given course of treatment. A guideline written for the treatment of depression, for example, may emphasize pharmaceuticals over talk therapy.

“The organizations writing the guidelines may be getting millions of dollars from big drug companies that want to promote a product. The people writing them may have similar conflicts of interest,” Poses said. NGC’s process provided a resource comparatively free of that kind of influence.

Underscoring how medical research like that maintained by the NGC can be politicized, AHRQ drew the ire of then-congressmember Tom Price in 2016 when it published a study critical of a drug manufactured by one of his campaign donors.According to ProPublica, one of Price’s aides emailed “at least half a dozen times” asking the agency to pull the critical research down. Price was the first director of HHS, AHRQ’s parent agency, under the Trump Administration, before resigningunder pressure last year over his spending on chartered flights.

The current director of AHRQ, Gopal Khanna — a Price appointee — is the first non-scientist to head the agency. His résumé includes mostly positions in information technology management, in state government in Minnesota and Illinois, and a brief stint in the George W. Bush White House. Shortly after he was hired in 2017, heannounced that data dissemination as one of his central priorities at the agency.

Mary Nix, Deputy Director of the Division of Practice Improvement at the Center for Evidence and Practice Improvement within AHRQ, cited budget cuts as the driving force behind NGC’s retirement. The site was most recently supported by a fee on some health insurance plans, which was instituted as part of the Affordable Care Act but is set to sunset in 2019. Nix estimates that the site would cost a “few hundred thousand” dollars per year to maintain even as a static archive.

Nix has been helping coordinate an effort to get some outside stakeholder to take over the site’s operations. She said she’s still hopeful, and even days before the site’s scheduled demise, AHRQ spokesperson Hunt told the Daily Beast that the search continued.

“Losing [the NGC] is really losing a valuable resource,” said Ana Maria Lopez, President of the American College of Physicians. She said the NGC is a primary source for her organization’s research, and noted that digital repositories like the NGC are only more critical today. “We’ll be thinking through what role we might be able to play here in helping to protect access to scientific information.”

Health Insurers Are Vacuuming Up Details About You — And It Could Raise Your Rates

by Marshall Allen - Maine Public - July 17, 2018

To an outsider, the fancy booths at a June health insurance industry gathering in San Diego, Calif., aren't very compelling: a handful of companies pitching "lifestyle" data and salespeople touting jargony phrases like "social determinants of health."

But dig deeper and the implications of what they're selling might give many patients pause: A future in which everything you do — the things you buy, the food you eat, the time you spend watching TV — may help determine how much you pay for health insurance.

With little public scrutiny, the health insurance industry has joined forces with data brokers to vacuum up personal details about hundreds of millions of Americans, including, odds are, many readers of this story.

The companies are tracking your race, education level, TV habits, marital status, net worth. They're collecting what you post on social media, whether you're behind on your bills, what you order online. Then they feed this information into complicated computer algorithms that spit out predictions about how much your health care could cost them.

Are you a woman who recently changed your name? You could be newly married and have a pricey pregnancy pending. Or maybe you're stressed and anxious from a recent divorce. That, too, the computer models predict, may run up your medical bills.

Are you a woman who has purchased plus-size clothing? You're considered at risk of depression. Mental health care can be expensive.

Low-income and a minority? That means, the data brokers say, you are more likely to live in a dilapidated and dangerous neighborhood, increasing your health risks.

"We sit on oceans of data," said Eric McCulley, director of strategic solutions for LexisNexis Risk Solutions, during a conversation at the data firm's booth. And he isn't apologetic about using it. "The fact is, our data is in the public domain," he said. "We didn't put it out there."

Insurers contend they use the information to spot health issues in their clients—and flag them so they get services they need. And companies like LexisNexis say the data shouldn't be used to set prices. But as a research scientist from one company told me: "I can't say it hasn't happened."

At a time when every week brings a new privacy scandal and worries abound about the misuse of personal information, patient advocates and privacy scholars say the insurance industry's data gathering runs counter to its touted, and federally required, allegiance to patients' medical privacy. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, only protects medical information.

"We have a health privacy machine that's in crisis," said Frank Pasquale, a professor at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law who specializes in issues related to machine learning and algorithms. "We have a law that only covers one source of health information. They are rapidly developing another source."

Patient advocates warn that using unverified, error-prone "lifestyle" data to make medical assumptions could lead insurers to improperly price plans – for instance raising rates based on false information – or discriminate against anyone tagged as high cost. And, they say, the use of the data raises thorny questions that should be debated publicly, such as: Should a person's rates be raised because algorithms say they are more likely to run up medical bills? Such questions would be moot in Europe, where a strict law took effect in May that bans trading in personal data.

This year, ProPublica and NPR are investigating the various tactics the health insurance industry uses to maximize its profits. Understanding these strategies is important because patients – through taxes, cash payments and insurance premiums—are the ones funding the entire health care system. Yet the industry's bewildering web of strategies and inside deals often have little do with patients' needs. As the series' first story showed, contrary to popular belief, lower bills aren't health insurers' top priority.

Inside the San Diego Convention Center, there were few qualms about the way insurance companies were mining Americans' lives for information — or what they planned do with the data.

Linking health costs to personal data

The sprawling convention center was a balmy draw for one of America's Health Insurance Plans' marquee gatherings. Insurance executives and managers wandered through the exhibit hall, sampling chocolate-covered strawberries, champagne and other delectables designed to encourage deal-making.

Up front, the prime real estate belonged to the big guns in health data: The booths of Optum, IBM Watson Health and LexisNexis stretched toward the ceiling, with flat screen monitors and some comfy seating. (NPR collaborates with IBM Watson Health on national polls about consumer health topics.)

To understand the scope of what they were offering, consider Optum. The company, owned by the massive UnitedHealth Group, has collected the medical diagnoses, tests, prescriptions, costs and socioeconomic data of 150 million Americans going back to 1993, according to its marketing materials.(UnitedHealth Group provides financial support to NPR.)

The company says it uses the information to link patients' medical outcomes and costs to details like their level of education, net worth, family structure and race. An Optum spokesman said the socioeconomic data is de-identified and is not used for pricing health plans.

Optum's marketing materials also boast that it now has access to even more. In 2016, the company filed a patent application to gather what people share on platforms like Facebook and Twitter, and link this material to the person's clinical and payment information. A company spokesman said in an email that the patent application never went anywhere. But the company's current marketing materials say it combines claims and clinical information with social media interactions.

I had a lot of questions about this and first reached out to Optum in May, but the company didn't connect me with any of its experts as promised. At the conference, Optum salespeople said they weren't allowed to talk to me about how the company uses this information.

It isn't hard to understand the appeal of all this data to insurers. Merging information from data brokers with people's clinical and payment records is a no-brainer if you overlook potential patient concerns. Electronic medical records now make it easy for insurers to analyze massive amounts of information and combine it with the personal details scooped up by data brokers.

It also makes sense given the shifts in how providers are getting paid. Doctors and hospitals have typically been paid based on the quantity of care they provide. But the industry is moving toward paying them in lump sums for caring for a patient, or for an event, like a knee surgery. In those cases, the medical providers can profit more when patients stay healthy. More money at stake means more interest in the social factors that might affect a patient's health.

Some insurance companies are already using socioeconomic data to help patients get appropriate care, such as programs to help patients with chronic diseases stay healthy. Studies show social and economic aspects of people's lives play an important role in their health. Knowing these personal details can help them identify those who may need help paying for medication or help getting to the doctor.

But patient advocates are skeptical health insurers have altruistic designs on people's personal information.

The industry has a history of boosting profits by signing up healthy people and finding ways to avoid sick people – called "cherry-picking" and "lemon-dropping," experts say.

Among the classic examples: A company was accused of putting its enrollment office on the third floor of a building without an elevator, so only healthy patients could make the trek to sign up. Another tried to appeal to spry seniors by holding square dances.

The Affordable Care Act prohibits insurers from denying people coverage based on pre-existing health conditions or charging sick people more for individual or small group plans. But experts said patients' personal information could still be used for marketing, and to assess risks and determine the prices of certain plans. And the Trump administration is promoting short-term health plans, which do allow insurers to deny coverage to sick patients.

Robert Greenwald, faculty director of Harvard Law School's Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation, said insurance companies still cherry-pick, but now they're subtler. The center analyzes health insurance plans to see if they discriminate. He said insurers will do things like failing to include enough information about which drugs a plan covers — which pushes sick people who need specific medications elsewhere. Or they may change the things a plan covers, or how much a patient has to pay for a type of care, after a patient has enrolled. Or, Greenwald added, they might exclude or limit certain types of providers from their networks – like those who have skill caring for patients with HIV or hepatitis C.

If there were concerns that personal data might be used to cherry-pick or lemon-drop, they weren't raised at the conference.

At the IBM Watson Health booth, Kevin Ruane, a senior consulting scientist, told me that the company surveys 80,000 Americans a year to assess lifestyle, attitudes and behaviors that could relate to health care. Participants are asked whether they trust their doctor, have financial problems, go online, or own a Fitbit and similar questions. The responses of hundreds of adjacent households are analyzed together to identify social and economic factors for an area.

Ruane said he has used IBM Watson Health's socioeconomic analysis to help insurance companies assess a potential market. The ACA increased the value of such assessments, experts say, because companies often don't know the medical history of people seeking coverage. A region with too many sick people, or with patients who don't take care of themselves, might not be worth the risk.

Ruane acknowledged that the information his company gathers may not be accurate for every person. "We talk to our clients and tell them to be careful about this," he said. "Use it as a data insight. But it's not necessarily a fact."

In a separate conversation, a salesman from a different company joked about the potential for error. "God forbid you live on the wrong street these days," he said. "You're going to get lumped in with a lot of bad things."

The LexisNexis booth was emblazoned with the slogan "Data. Insight. Action." The company said it uses 442 nonmedical personal attributes to predict a person's medical costs. Its cache includes more than 78 billion records from more than 10,000 public and proprietary sources, including people's cellphone numbers, criminal records, bankruptcies, property records, neighborhood safety and more. The information is used to predict patients' health risks and costs in eight areas, including how often they are likely to visit emergency rooms, their total cost, their pharmacy costs, their motivation to stay healthy and their stress levels.

People who downsize their homes tend to have higher health care costs, the company says. As do those whose parents didn't finish high school. Patients who own more valuable homes are less likely to land back in the hospital within 30 days of their discharge. The company says it has validated its scores against insurance claims and clinical data. But it won't share its methods and hasn't published the work in peer-reviewed journals.

McCulley, LexisNexis's director of strategic solutions, said predictions made by the algorithms about patients are based on the combination of the personal attributes. He gave a hypothetical example: A high school dropout who had a recent income loss and doesn't have a relative nearby might have higher than expected health costs.

But couldn't that same type of person be healthy? I asked.

"Sure," McCulley said, with no apparent dismay at the possibility that the predictions could be wrong.

McCulley and others at LexisNexis insist the scores are only used to help patients get the care they need and not to determine how much someone would pay for their health insurance. The company cited three different federal laws that restricted them and their clients from using the scores in that way. But privacy experts said none of the laws cited by the company bar the practice. The company backed off the assertions when I pointed that the laws did not seem to apply.

LexisNexis officials also said the company's contracts expressly prohibit using the analysis to help price insurance plans. They would not provide a contract. But I knew that in at least one instance a company was already testing whether the scores could be used as a pricing tool.

Before the conference, I'd seen a press release announcing that the largest health actuarial firm in the world, Milliman, was now using the LexisNexis scores.

I tracked down Marcos Dachary, who works in business development for Milliman. Actuaries calculate health care risks and help set the price of premiums for insurers. I asked Dachary if Milliman was using the LexisNexis scores to price health plans and he said: "There could be an opportunity."

The scores could allow an insurance companies to assess the risks posed by individual patients and make adjustments to protect themselves from losses, he said. For example, he said, the company could raise premiums, or revise contracts with providers.

It's too early to tell whether the LexisNexis scores will actually be useful for pricing, he said. But he was excited about the possibilities. "One thing about social determinants data – it piques your mind," he said.

Dachary acknowledged the scores could also be used to discriminate. Others, he said, have raised that concern. As much as there could be positive potential, he said, "there could also be negative potential."

Erroneous inferences from group data

It's that negative potential that still bothers data analyst Erin Kaufman, who left the health insurance industry in January. The 35-year-old from Atlanta had earned her doctorate in public health because she wanted to help people, but one day at Aetna, her boss told her to work with a new data set.

To her surprise, the company had obtained personal information from a data broker on millions of Americans. The data contained each person's habits and hobbies, like whether they owned a gun, and if so, what type, she said. It included whether they had magazine subscriptions, liked to ride bikes or run marathons. It had hundreds of personal details about each person.

The Aetna data team merged the data with the information it had on patients it insured. The goal was to see how people's personal interests and hobbies might relate to their health care costs.

But Kaufman said it felt wrong: The information about the people who knitted or crocheted made her think of her grandmother. And the details about individuals who liked camping made her think of herself. What business did the insurance company have looking at this information? "It was a data set that really dug into our clients' lives," she said. "No one gave anyone permission to do this."

In a statement, Aetna said it uses consumer marketing information to supplement its claims and clinical information. The combined data helps predict the risk of repeat emergency room visits or hospital admissions. The information is used to reach out to members and help them and plays no role in pricing plans or underwriting, the statement said.

Kaufman said she had concerns about the accuracy of drawing inferences about an individual's health from an analysis of a group of people with similar traits. Health scores generated from arrest records, home ownership and similar material may be wrong, she said.

Pam Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum, a nonprofit that advocates for privacy in the digital age, shares Kaufman's concerns. She points to a study by the analytics company SAS, which worked in 2012 with an unnamed major health insurance company to predict a person's health care costs using 1,500 data elements, including the investments and types of cars people owned.

The SAS study said higher health care costs could be predicted by looking at things like ethnicity, watching TV and mail-order purchases.

"I find that enormously offensive as a list," Dixon said. "This is not health data. This is inferred data."

Data scientist Cathy O'Neil said drawing conclusions about health risks on such data could lead to a bias against some poor people. It would be easy to infer they are prone to costly illnesses based on their backgrounds and living conditions, said O'Neil, author of the book Weapons of Math Destruction, which looked at how algorithms can increase inequality. That could lead to poor people being charged more, making it harder for them to get the care they need, she said. Employers, she said, could even decide not to hire people with data points that could indicate high medical costs in the future.

O'Neil said the companies should also measure how the scores might discriminate against the poor, sick or minorities.

American policymakers could do more to protect people's information, experts said. In the United States, companies can harvest personal data unless a specific law bans it, although California just passed legislation that could create restrictions, said William McGeveran, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School. Europe, in contrast, passed a strict law called the General Data Protection Regulation, which went into effect in May.

"In Europe, data protection is a constitutional right," McGeveran said.

Pasquale, the University of Maryland law professor, said health scores should be treated like credit scores. Federal law gives people the right to know their credit scores and how they're calculated. If people are going to be rated by whether they listen to sad songs on Spotify or look up information about AIDS online, they should know, Pasquale said. "The risk of improper use is extremely high," he said. "And data scores are not properly vetted and validated and available for scrutiny."

A creepy walk down memory lane

As I reported this story I wondered how the data vendors might be using my personal information to score my potential health costs. So, I filled out a request on the LexisNexis website for the company to send me some of the personal information is has on me. A week later a somewhat creepy, 182-page walk down memory lane arrived in the mail. Federal law only requires the company to provide a subset of the information it collected about me. So that's all I got.

LexisNexis had captured details about my life going back 25 years, many that I'd forgotten. It had my phone numbers going back decades and my home addresses going back to my childhood in Golden, Colo. Each location had a field to show whether the address was "high risk." Mine were all blank. The company also collects records of any liens and criminal activity, which, thankfully, I didn't have.

My report was boring, which isn't a surprise. I've lived a middle-class life and grown up in good neighborhoods. But it made me wonder: What if I had lived in "high-risk" neighborhoods? Could that ever be used by insurers to jack up my rates — or to avoid me altogether?

I wanted to see more. If LexisNexis had health risk scores on me, I wanted to see how they were calculated and, more importantly, whether they were accurate. But the company told me that if it had calculated my scores it would have done so on behalf of their client, my insurance company. So, I couldn't have them.

Transforming Health Care from the Ground Up

by Vijay Govindarajan and Ravi Ramamurdi - Harvard Business Review - July-August 2018

The U.S. health care system desperately needs reform to rein in costs, improve quality, and expand access. Federal policy changes are essential, of course; however, top-down solutions alone cannot fix a wasteful and misdirected system. The industry also needs transformation from the bottom up, by entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs—the kind of trailblazers we’ve been studying over the past several years. In our work, we’ve seen innovations championed by CEOs of start-ups who understand that needed reform is not going to come anytime soon from government regulators. We’ve also seen changes driven by doctors, nurses, administrators, employers, and even patients who are devising solutions to the problems they face every day in an ill-built system.

In this article, we look at two examples of bottom-up innovation involving a radical transformation of health care delivery. The University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) created a homegrown telehealth network to increase patient access to care; Iora Health developed a new business model that doubled down on primary care to reap large savings in secondary and tertiary care. To understand the strategies that drove each effort, we interviewed the organizations’ principals, investors, and employees, along with other industry leaders, as part of our six-year study of innovations in health care delivery around the world. The results of these two initiatives were astonishing. Mississippi’s telehealth network has saved lives and money and revived struggling rural hospitals and communities. Ten years out, satisfaction is high among patients (93.4%) and local hospital administrators (87.5%). Over seven years, Iora has reduced hospitalizations of its patients by 35% to 40% and lowered its total health care costs by 15% to 20%, while improving patients’ overall health.

These successful initiatives—one from an incumbent health care provider and one from a business start-up—demonstrate the potential of creative leaders to reshape the U.S. health system. Let’s look at each in turn.

Innovation by Incumbents: Mississippi Telehealth

In 1999 Mississippi had only one top-tier hospital, the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, and 99 acute care hospitals, three-quarters of which were in rural areas. Many of those facilities were “critical access hospitals”—a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services designation for rural hospitals with no more than 25 beds and located more than 35 miles from another facility. The acute care hospitals had no medical specialists on staff, performed no surgeries, and even lacked labor and delivery units, as they had no obstetricians. By law, the critical access facilities could provide inpatient acute care only on a limited basis. Many lacked the imaging equipment required to diagnose emergent conditions, and not one of them had a ventilator. Patients requiring serious emergency care were often transported from those hospitals to UMMC, a solution as expensive as it was medically risky.

As UMMC’s initiative demonstrated, telehealth systems scale exceptionally well.

Kristi Henderson, UMMC’s clinical director of nursing in the ER at the time, saw the overcrowding in the trauma center in Jackson and the endless stream of rural patients who had traveled some distance seeking care. Why not reverse the flow, she thought? Why not build capacity in the rural clinics by sharing the medical expertise concentrated at UMMC through a telehealth system?

A seasoned health care professional, Henderson knew that a state-funded, top-down telehealth effort was about as likely as a snowstorm in July. So she began to develop a pilot project to link the trauma team in Jackson with the primary care doctors and nurse practitioners who staffed most of the critical access hospitals. The local practitioners would process admissions, stabilize patients, perform simple procedures, order lab work and EKGs, and take basic images. The emergency team in Jackson would observe the patients on dedicated TV screens, read the X-rays and other images, diagnose the problems, talk the local practitioners through the treatment plans, and be available for follow-up care, either in person in Jackson or remotely through the network.

This TelEmergency network would concentrate the scarcest expertise and equipment in the Jackson “hub,” which handled advanced procedures, while the community hospitals would serve as gateways and service points (“spokes”) for simpler procedures. The telehealth network would save money by reducing patient transfers and instead treating more people in local hospitals, where costs were as little as half those at UMMC. The network would also help keep small, financially insecure hospitals afloat by increasing their emergency room services and revenue streams.

As UMMC’s initiative demonstrated, telehealth systems scale exceptionally well. Henderson began with three pilot community hospitals in 2003, and over the following 10 years, she expanded the program statewide, adding 14 more locations. In 2008, UMMC’s telehealth network began expanding services beyond the ER, and today it provides 35 specialty services at more than 200 hospitals and service centers, including schools and prisons, throughout Mississippi.

This is a dramatic example of effective bottom-up innovation. Henderson’s experience working within the health care system gave her insight into the human, financial, and technology challenges that nurses and other health care professionals faced every day, and she methodically set about addressing them. She also brought to bear a trait we’ve seen in all the innovators we’ve studied: a constitutional inability to take no for an answer. Here’s how she did it.

Assembling resources.

Trained as a nurse practitioner, Henderson believed passionately in a collaborative model of health care delivery that respected the capabilities of all health care workers. But her enthusiasm was not universally shared. Before she connected her first local hospital, she spent three years persuading state medical, nursing, and pharmacy boards to give the telehealth network a chance. She listened and honed her case as the Mississippi medical establishment fretted about the quality of long-distance care, the reliability of technology, the ability of nurse practitioners to learn new skills, and the risk that telemedicine would cannibalize the practices of rural physicians.

Every incumbent innovator faces such resistance from legacy stakeholders. Henderson tackled the issues one at a time, assembling the resources needed to launch the system at pilot sites. Along with her boss, Dr. Robert Galli, who headed up emergency care at UMMC, and the team’s technology wizard, Greg Hall, Henderson worked with experts in the field to identify and secure equipment that was reliable, affordable, and easy to use. Next, Henderson persuaded administrators to allocate some space adjacent to UMMC’s emergency department to serve as the telemedicine console room. She and her colleagues carried bulky TV consoles and equipment to rural hospitals and gave a “theatrical performance,” as she put it, demonstrating the system. Leveraging the hospital’s state discount from local telecom providers, she was able to get affordable T1 lines—the most reliable but most expensive type of telecommunications connection. To demonstrate that the system would provide adequate resolution over long distances, her team connected it via satellite phone to a remote clinic in Kigali, Rwanda. Success.

From the beginning, Henderson understood that UMMC’s telehealth network would require a culture change, because it would shift tasks away from one set of actors and empower others. To overcome skepticism and develop needed skills, Henderson created a comprehensive telehealth curriculum taught by UMMC medical specialists for nurse practitioners at rural hospitals. The training program, which included written exams and certifications of completion, won over some doubters and built trust between the hub specialists and the spoke practitioners.

It took Henderson from 1999 to 2002 to overcome each barrier and get the green light to hook up the first client: a consortium of three critical access hospitals that were struggling to stay afloat. “The group was either so incredibly visionary or so incredibly desperate that they wanted to participate,” says Henderson. Regulators kept the network on a tight leash, with periodic audits and surveys, while the Mississippi medical establishment continued to worry about the loss of hands-on contact between patient and doctor. But Henderson was quickly able to demonstrate that patients were benefiting. Because the long-distance technology allowed them to avoid visits to specialists in Jackson, patients were able to remain close to loved ones during treatment, lose less work time, and save money on travel expenses, thereby lowering the impact of accident or illness on their families. In addition, they began to trust their local hospitals more and seek treatment sooner.

Securing funds.

Like most bottom-up innovations, the UMMC telehealth network had to scramble for money. For eight years, the program had no dedicated staff and no hospital budget. There was no private equity investment, and the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation provided no grants. Instead, Henderson raised $4.8 million from a local private foundation and several relatively obscure federal programs for rural outreach.

Having secured just enough money to support the network infrastructure, Henderson turned to a bigger problem: how to fund the telehealth services themselves. State law prohibited Mississippi insurers from reimbursing charges for telehealth consults. So Henderson devised a hybrid payment system in which insurers reimbursed the rural hospitals for services provided locally, such as practitioners’ time and lab tests, and the local hospitals paid UMMC a monthly “availability fee,” based on an estimated number of hours of remote consultation, to cover the services of the physicians in Jackson. In this way, new revenue was generated in both the hub and the spoke hospitals, pressure was taken off UMMC’s overextended resources, and patients got better access to care.