Private Equity Is a Parasite Consuming the US Health System

Private equity has succeeded in depicting itself as part of the productive economy of health care services. even as it is increasingly being recognized as being parasitic. The essence of this toxic parasitism is not only to drain the host’s nourishment, but also to dull the host’s brain so that it often does not even recognize that the parasite is there. This is the illusion that health care services in the United States suffer under today.

Parasitic private equity is consuming US health care from the inside out, weakening its structure and strength and enriching investors at the expense of patient care and patients. Incremental health reforms have failed. It’s time to move past political barriers to achieve consensus on real reform. says J.E. McDonough, Professor of Practice at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Private equity firms are financial termites devouring the woodwork and foundations of the US health care system. Laura Katz Olson documents in her new book, Ethically Challenged: Private Equity Storms US Health Care, “PE firms are gobbling up physician and dental practices; homecare and hospital agencies; mental health, substance abuse, eating disorder, and autism services; urgent care facilities; and emergency medical transportation.” Private equity has become a growing and diversified part of the American health care economy. Demonstrated results of private equity ownership include higher patient mortality, higher patient costs, fewer jobs, poorer quality, and closed facilities.

What is Private Equity?

A private equity fund is a large unregulated pool of money run by financiers who use that money to invest in and/or buy companies and restructure them. They seek to recoup gains through dividend pay-outs or later sales of the companies to strategic acquirers or back to the public markets through initial public offerings. But that doesn’t capture the scale of the model. There are also private equity-like businesses who scour the landscape for companies, buy them, and then use extractive techniques such as price gouging or legalized forms of complex fraud to generate cash by moving debt and assets like real estate among shell companies. PE funds also lend money and act as brokers, and are morphing into investment bank-like institutions. Some of them are public companies.

While the movement is couched in the language of business, using terms like strategy, business models returns of equity, innovation, and so forth, and proponents refer to it as an industry, private equity is not business. On a deeper level, private equity is the ultimate example of the collapse of the enlightenment concept of what ownership means. Ownership used to mean dominion over a resource, and responsibility for caretaking that resource. PE is a political movement whose goal is extend deep managerial controls from a small group of financiers over the producers in the economy. Private equity transforms corporations from institutions that house people and capital for the purpose of production into extractive institutions designed solely to shift cash to owners and leave the rest behind as trash. Like much of our political economy, the ideas behind it were developed in the 1970s and the actual implementation was operationalized during the Reagan era.

Matt Stoller, distinguished journalist, describes the essential business plan of private equity:

Financial engineers… raise large amounts of money and borrow even more to buy firms and loot them. These kinds of private equity barons aren’t healthcare specialists who help finance useful health products and services, they do cookie cutter deals targeting firms/practices/hospitals they believe have market power to raise prices, who can lay off workers or sell assets, and/or have some sort of legal loophole advantage. Often, they will destroy the underlying business. The giants of the industry, from Blackstone to Apollo to Bain, are the children of 1980s junk bond king and fraudster Michael Milken. They are essentially super-sized mobsters.

Economists Akerloff, Romer, Public Health Professor McDonough elaborate:

The classic description of this looting-for-profit practice process is presented by economists George Akerloff and Paul Romer : “Firms have an incentive to go broke for profit at society’s expense (to loot) instead of to go for broke (to gamble on success). Bankruptcy for profit will occur if poor accounting, lax regulation, or low penalties for abuse give owners an incentive to pay themselves more than their firms are worth and then default on their debt obligations.” The fact that paper gains from stock prices can be wiped out when financial storms occur makes financial capitalism less resilient than the industrial base of tangible capital investment.

Professor McDonough notes that in the past 45 years the US economy has become heavily financialized more rapidly and decisively than in our peer nations. “Just as General Electric’s Jack Welch transformed (ruined) his company from a goods manufacturer to a financial services company, so have financial flood waters now penetrated every corner of American health care. Private equity is winning, and any health care organization is a potential takeover target. Patients and patient visits become commodities and data points to be exploited for high profits by private equity’s “financial intermediaries who view healthcare organizations as vehicles for extracting wealth.”

Don McCanne, M.D., Physicians for a Nation Health Program (PNHP) describes private equity modus operandi:

All around us we see private equity firms moving into health care by clustering specific specialties into new corporate entities. These equity firms may profess to infuse quality and efficiency into the systems they create, but their true objective is not altruism. Their interest is found in their label: equity, the more ($$) the better. Distinguished California physician, Don McCanne, M.D. of PNHP, describes private equity modus operandi:

1) acquire a relatively large platform practice in a given specialty

2) then acquire smaller practices in the same geographic area and merge them into the platform practice

3) use debt to finance the acquisitions and assign that debt to the acquired practices,

4) find ways to increase net revenue from the agglomerated practices

5) sell the agglomerated practices within 3 to 5 years for considerably more than the price paid by the private equity company.

Conveniently, Dr. McCanne notes, the debt is left with the practices they purchased, and the equity investors walk away with the money. How does this benefit the patients? How does this benefit the health care professionals? We know how it benefits the equity firm investors, but does anyone seriously contend that this is what health care should be about? But that’s what it has become.

Consequences:

1) Consider Noble Health, a private equity-backed Kansas City startup launched in 2019. In rural Missouri, Noble acquired Audrain and Callaway Community Hospitals in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2) In March 2022, all hospital services ceased with the furlough of 181 employees.

3) Notes Kaiser Health News, “…venture capital and private equity firm Nueterra Capital launched Noble in December 2019 with executives who had never run a hospital, including Donald R. Peterson, a co-founder who prior to joining Noble had been accused of Medicare fraud.”

4) St. Joseph’s Home for the Aged in Richmond, Virginia, as retold in The New Yorker.

5) A New Jersey private equity firm called the Portopiccolo Group bought the home, reduced stuff, cut amenities, and set the stage for a deadly outbreak of COVID-19” that included a doubling in patient deaths.

6) The numbers of stories of private equity-generated health system harm grows rapidly. And if the health part of the business goes bust, as occurred in 2019 at Philadelphia’s now closed Hahnemann Hospital, the underlying real estate still offers rich rewards.

7) Patients at North Carolina-based Atrium Health get what looks like an enticing pitch when they go to the nonprofit hospital system’s website: a payment plan from lender AccessOne. The plans offer “easy ways to make monthly payments” on medical bills, the website says. You don’t need good credit to get a loan. Everyone is approved. Nothing is reported to credit agencies. Very high interest rates are standard however

8) In Minnesota, Allina Health encourages its patients to sign up for an account with MedCredit Financial Services to “consolidate your health expenses.” Very high interest.

9) In Southern California, Chino Valley Medical Center, part of the Prime Healthcare chain, touts “promotional financing options with the CareCredit credit card to help you get the care you need, when you need it.” As usual, very high interest rates.

As Americans are overwhelmed with medical bills, patient financing is now a multibillion-dollar business, with private equity and big banks lined up to cash in when patients and their families can’t pay for care. By one estimate from research firm IBISWorld, profit margins top 29% in the patient financing industry, seven times what is considered a solid hospital margin.

Mental health services controlled by a buyout king

The Private Equity Newsletter reports that psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers once ran their own practices. Now the local therapist office could be controlled by a buyout king. Venture capitalists and private-equity firms are pouring billions of dollars into mental-health businesses, including psychology offices, psychiatric facilities, telehealth platforms for online therapy, new drugs, meditation apps and other digital tools. Nine mental-health startups have reached private valuations exceeding $1 billion last year, including Cerebral Inc. and BetterUp Inc.

Demand for these services is rising as more people deal with grief, anxiety and loneliness amid lockdowns and the rising death toll of the Covid-19 pandemic, making the sector ripe for investment, according to bankers, consultants and investors. They say the sector has become more attractive because health plans and insurers are paying higher rates than in the past for mental-health care, and virtual platforms have made it easier for clinicians to provide remote care.

“Since Covid, the need has gone through the roof,” said Kevin Taggart, managing partner at Mertz Taggart, a mergers-and-acquisitions firm focused on the behavioral-health sector. “Every mental-health company we are working for is busy. A lot of them have wait lists.”

In the first year of the pandemic, prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25%, the World Health Organization said in March. About one-third of Americans are reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of behavioral-health acquisitions jumped more than 35% to 153 in 2021 versus the previous year, and of those, 123 involved private-equity firms, according to Mertz Taggart. In the first quarter of this year, there were 41 acquisitions, of which 30 involved PE firms.

The push into mental health carries risks. A rush of private-equity firms could send prices for practices higher, reducing potential profits. A risk for patients and clinicians is that new owners could focus on profits rather than outcomes, perhaps by pressuring clinicians to see more patients than they can handle. If care becomes less personal and private, patient care might also suffer.

Online mental-health company Cerebral and other telehealth startups have begun to face scrutiny over their prescribing practices. The Wall Street Journal has reported that some of Cerebral’s nurse practitioners said they felt pressure to prescribe stimulants. This past week, Cerebral said it would pause prescribing controlled substances such as Adderall to treat ADHD in new patients. Last year, Cerebral logged a $4.8 billion valuation.

Investors poured $5.5 billion into mental-health technology startups globally last year, up 139% from 2020, according to a report by CB Insights, an analytics firm. Of that, $4.5 billion was spent on U.S. firms. They range from platforms like SonderMind that match people with clinicians to meditation apps like Calm.

How bad has it gotten?

Private equity-owned healthcare companies have also seen the following issues:

- Reduced staffing, or filling beds without adequate staffing ratios

- Over-reliance on unlicensed staff to reduce labor costs

- Failure to provide adequate training

- Pressure on providers to provide unnecessary and potentially costly services

- Violation of regulations required for participants in Medicare and Medicaid such as anti-kickback provisions, creating litigation risk

Dentristry

Kaiser Health News (KHC) reports that private equity business tactics have been linked to scandalously bad care at some dental clinics that treated children from low-income families.

- In early 2008, a Washington, D.C., television station aired a shocking report about a local branch of the dental chain Small Smiles that included video of screaming children strapped to straightjacket-like “papoose boards” before being anesthetized to undergo needless operations like baby root canals.

- Five years later, a U.S. Senate report cited the TV exposé in voicing alarm at the “corporate practice of dentistry in the Medicaid program.” The Senate report stressed that most dentists turned away kids enrolled in Medicaid because of low payments and posed the question: How could private equity make money providing that care when others could not?

- “The answer is ‘volume,’” according to the report.

- Small Smiles settled several whistleblower cases in 2010 by paying the government $24 million. At the time, it was providing “business management and administrative services” to 69 clinics nationwide, according to the Justice Department. It later declared bankruptcy.

According to the 2018 lawsuit filed by his parents, Zion Gastelum was hooked up to an oxygen tank after questionable root canals and crowns “that was empty or not operating properly” and put under the watch of poorly trained staffers who didn’t recognize the blunder until it was too late.

- Zion never regained consciousness and died four days later at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, the suit states. The cause of death was “undetermined,” according to the Maricopa County medical examiner’s office. An Arizona state dental board investigation later concluded that the toddler’s care fell below standards, according to the suit.

- Less than a month after Zion’s death in December 2017, the dental management company Benevis LLC and its affiliated Kool Smiles clinics agreed to pay the Justice Department $24 million to settle False Claims Act lawsuits.

- The government alleged that the chain performed “medically unnecessary” dental services, including baby root canals, from January 2009 through December 2011.

- In their lawsuit, Zion’s parents blamed his death on corporate billing policies that enforced “production quotas for invasive procedures such as root canals and crowns” and threatened to fire or discipline dental staff “for generating less than a set dollar amount per patient.”

- Kool Smiles billed Medicaid $2,604 for Zion’s care, according to the suit. FFL Partners did not respond to requests for comment. In court filings, it denied liability, arguing it did not provide “any medical services that harmed the patient.”

Professor Olson concludes that private equity does not belong in medicine or health care.

Laura Katz Olson, Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Lehigh University and author of “Ethically Challenged: Private Equity Storms U.S. Health Care,” concludes, private equity does not belong in medicine at all and should it be banned.

We really need to prohibit, I think, the corporate practice of medicine, period. If you look at the private equity playbook, its only goal is to make outsized profits – they can’t make ordinary profits. If they make ordinary, respectable profits, their investors will go somewhere else because of the risk.

Private equity doesn’t care whether the product is Roto-Rooter or hospice. That’s one of the major differences between PE and a regular company, which may care about the community, the reputation of the company, and the quality of the product. They want to keep their customers. They care about the future.

But private equity doesn’t work like that. Because private equity often aims to sell a company after four or five months, they don’t care about the future. They don’t care about the product at all. Private equity is antithetical to our health care system.

So yes, we need to ban private equity from health care. But given that it’s not going to happen, I would say that we need to prohibit the corporate practice of medicine – anybody can make a case for that.

You can eliminate their tax advantages.

You can limit the debt imposed on companies, especially in the health sector. You could easily control consolidation and monopolies in the health sector.

You could use specific anti-trust laws. I would definitely forbid investment by retail customers such as their 401(k)s.

I would forbid non-disclosure and non-disparagement agreements, which make it so difficult to obtain information. I had such a hard time interviewing people. When I could get people to talk to me – and that was really hard — they were extraordinarily careful.

I would also prohibit “stealth branding”—where the PE firm buys a chain, like a dental chain, but gives each office its own name, like Marilyn’s Happy Dental Care. It’s very deceptive.

PE players and firms don’t tend to be household names. They’ve really managed to fly under the radar. Here are some names that came up frequently in the research. Folks to look out for:

Bain Capital, the PE company that Mitt Romney still profits from, is one.

The Carlyle Group has really been involved in recruiting high-ranking people from the government – one of its co-founders, David Rubenstein, served as Deputy Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy during the Carter administration.

George H.W. Bush became a senior member of its Asia advisory, and so on.

KKR, of course, is one of the biggest. They control a lot in health care.

Dr. Olson concludes with concerns that can effect all communities. “As PE gets more and more money – with these pension funds, and especially if they get their hands into the 401(k)s—they’re just going to keep buying up anything and everything. And it’s not just health care. More and more of these firms are appearing and getting into more and more industries. As young people, or even older people involved in the well-established financial firms, realize how much money is involved, they just start a PE firm. Look at Jared Kushner [Affinity Partners]. It’s a very worrisome situation."

Profiteers turn hospice into a $22 billion industry

by Diane Archer - Just Care - November 30, 2022

Ava Kofman writes for the New Yorker on the profiteers who have turned hospice care into a $22 billion dollar a year industry. Rather than being about dying with dignity, hospice is too often all about the money. Since quality varies tremendously, it’s critical to choose a hospice agency carefully.

Today, about half of all Americans choose hospice at the end of life. With hospice, people deemed to have six months or less to live choose to forgo treatment for their medical conditions and instead receive palliative care to ensure their comfort. But, now that corporations see the dollar signs in hospice, electing hospice care can pose risks for patients. (N.B. People with Medicare can opt out of hospice at any time and receive Medicare-covered treatment for their conditions.)

People tend to learn about hospice from their treating physicians. But, some for-profit hospices hire staff to scout out hospice patients. Hospice staff offer vulnerable people free medicine, nursing care and more if they’ll sign up for hospice, regardless of whether they actually qualify for hospice.

Hospice agencies sometimes set “ungodly quotas” on their sales teams, expecting them to find large numbers of people who qualify for the hospice benefit. To meet their quotas, hospice staff recruit people into hospice who are not terminally ill but who the hospice agency can certify as terminally ill.

At AseraCare, Kofman reports that staff are trained to turn chronic conditions like shortness of breath into a terminal condition, so that patients qualify for hospice. The corporations know exactly how to tap into government dollars. Often, they are running nursing home chains as well. Private equity also is in the hospice business.

Much like Medicare Advantage plans, which often have histories of committing fraud or of settling fraud claims with the government, some hospice companies have similar histories. But, the government continues contracting with them. Consequently, Kofman reports that “companies in the hospice business can expect some of the biggest returns for the least amount of effort of any sector in American health care.”

Medicare pays a flat daily rate to the hospice, even if it delivers few services. Medicare only requires the hospice to send a nurse to visit hospice patients twice a month. Medicare does require repayment from hospice agencies if their hospice patient population overall lives longer than six months. But, the agencies can get around that–they simply drop patients before the six months elapse.

Hospice should ensure a person’s end of life is as good and comfortable as possible. It also should reduce health care costs because comfort care is far less expensive than hospitalizations at the end of life. But, in the hands of profiteers, who take the money paid them and don’t offer compassionate care, it is a huge waste.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) appears to do a poor job of overseeing the hospices it contracts with. One review of hospices found that most hospices had serious failings. Hospice agencies did not manage pain as required or have trained staff. But, as with Medicare Advantage plans, CMS almost never punishes the bad actors.

What will Congress do about this?

Toledo, Ohio has given its residents a new and unusual holiday gift: the promise of medical debt relief.

In early November, its city council voted to use $800,000 of American Rescue Plan Act funding to wipe out the medical debt of residents in need, with the help of an organization called RIP Medical Debt. Lucas County, where Toledo is the county seat, even said it would match the amount for a total of $1.6 million toward eliminating medical debt.

"I think this is going to help a lot of people with putting food back on the table, paying the rent, paying your utilities, help them go back to the doctor," Michele Grim, the city councilwoman and state representative-elect who led the push for the program, told MedPage Today.

With the $1.6 million, officials expect to wipe out $240 million worth of debt, Grim said. A spokesperson for Lucas County said it is "currently pursuing the funding source."

Grim had heard of a similar program in Cook County, Illinois that committed $12 million in federal money to cancel medical debt. The ordinance she proposed was held three times, but finally passed 7-5 on November 9.

The move is also expected to give a leg-up to Toledo's economy. "Here, our wages are pretty stagnant," Grim said. "And we have a higher poverty rate than the national average. So it's really going to help a lot of people, and help aid in economic recovery for Toledo and Lucas County residents."

RIP Medical Debt, which was founded by former debt collectors, buys up unpaid medical debt at much lower amounts than the outstanding total, cancelling the debt instead of collecting on it. The unpaid debt is purchased in secondary marketplaces, and more recently, directly from hospitals and health systems now that a federal advisory opinion has approved that model.

Those eligible for the debt cancellation -- people who make 400% of the poverty level or below, or whose debts make up at least 5% of their total income -- won't have to apply. Instead, after the debt is sold, RIP Medical Debt will send them a letter in the mail notifying them that they're debt-free.

"It's a very uniquely American problem," Grim said. "And this is a way to help give people relief."

Allison Sesso, MPA, president and CEO of RIP Medical Debt, told MedPage Today that the impact of this relief can be huge. Medical debt, she said, can erode mental health, prompt people to borrow money from friends and family, take on extra jobs, or even avoid seeking medical care altogether.

"The fact that for pennies on the dollar, we're able to help so many people remove this burden -- why not? It makes a whole lot of sense. And it really can help propel them forward," Sesso said. Beneficiaries have told the organization that it helped them "climb back up" from other debts, "because [they] don't feel completely buried," Sesso said.

Census Bureau data show that around 17% of U.S. adults owed a medical debt, while a nationally representative Kaiser Family Foundation survey of 2,375 adults found 41% reported being in some kind of medical debt.

A number of Toledo-area hospitals indicated their interest in negotiating with RIP Medical Debt, Sesso said. Once contracts with the local government are finalized, the organization can begin the process of talking with hospitals and physician groups who would provide them the information about patients' eligibility. Overall, she said the process shouldn't take more than a year.

Sesso and Grim said it's a straightforward idea that's picking up steam. "It's not been that long that we've been asked to have a direct relationship with hospitals," Sesso said. "And we're growing as an entity and I think we're just starting to get the word out about the fact that we exist. More and more hospitals are coming on board."

Grim said she received around a half-dozen calls from other municipalities interested in implementing the same kind of initiative, and Sesso said five to 10 local governments had reached out. Both said they could not disclose additional details before decisions were finalized.

"It's a simple program that really does help aid in the economic recovery of Americans, and it's really something that the American Rescue Plan dollars were designed to do," Grim said.

Sessob also noted that while her organization's solution is a good one, it's treating a symptom, not the cause, of a broken healthcare system.

"As we say, you can walk and chew gum at the same time, right?" Sesso said. "So we can be resolving the issue one person at a time, while also pointing to the fact that there's got to be bigger solutions hashed out."-

Claire Mortimer - Nurse Practitioner - Blue Hill, Maine - November 30. 2022

To be very clear, free speech is when you give me money

by Alexandra Petri - Washington Post - November 30, 2022

“This is a battle for the future of civilization. If free speech is lost even in America, tyranny is all that lies ahead.”

— Elon Musk, on Twitter, the social media site he owns

If you don’t pay me money for my product, that means that this great country is wrecked! Wrecked on the shoals of oppression and political correctness!

Free speech is when you pay me money for goods or services. That’s free speech. When you do not give me money, that is censorship. Every second that you spend not paying me money for my services is another arrow stuck into the craw of liberty. Ah, liberty bleeds, and I weep for her! Please give me thousands of dollars; it is the only thing that can save her. Even if you must give them to me in small increments of $8 at a time, that is better than nothing. I believe that if you give me enough money (speech), we can still rescue this godforsaken country!

You might have thought that free speech was when a corporation gave a lot of money to a politician. This is a very, very important form of free speech, and it is getting freer all the time! But that is certainly not the only kind of speech you can make. Just as important is when you take your small-dollar amounts and press them into the hands of a billionaire, or when an advertiser does the same thing with a larger dollar amount.

No, I am not taking advantage of you. I am offering to give you a voice. It is very sad that you are letting liberty die because you are refusing to give me your wallet. I can’t believe you hate free speech so much!

Oh, okay, I see where there may be some slight confusion: There is the word “free,” right there, at the start of “free speech.” It almost sounds as though you didn’t need to pay for it! But this is a common misunderstanding. This is free as in “buy one, get one,” the kind of free that is only free if you have made a purchase first.

Why I remember when our Founders, our brave Founders, fought so strongly and so bravely for free speech. Benjamin Franklin stood there begging and beseeching the business owners of his day to put their advertisements in his Poor Richard’s Almanac. Everyone knew then as they know today that the only true free speech is when you pay somebody money to run advertisements for your business. The Bill of Rights is absolutely clear about this. Why do you think it is called a bill if not because rights require somebody to pay money to somebody else?!

And the people who do not have money? What of them? As though they had anything to say!

Alexandra Petri is a Washington Post columnist offering a lighter take on the news and opinions of the day. She is the author of the essay collection "Nothing Is Wrong And Here Is Why." Twitter

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/11/30/elon-musk-twitter-free-speech-money/

Nex-gen reform part 2: Ending variable pricing in health care

Last week, I laid out the case for federalizing Medicaid as a first plank in a next-gen health care payment reform agenda. Today, I will explain why we must put an end the most wasteful practice in the nation’s dysfunctional payment system: variable pricing.

Over the past several years, the health care press has repeatedly pointed out the wild discrepancies in health care prices – both between hospitals and within hospitals. Using data obtained through the recently enacted hospital pricing transparency rule, NPR’s Julie Appleby found a routine colonoscopy in Virginia cost some insurers over $10,000 even though the statewide average was $2,763. A single hospital in Hollywood, Florida, had more than a dozen prices for different insurers, ranging from a low or $550 to $6,400 for the same colonoscopy.

Most such stories (including the NPR piece) ignore the fact that most prices for the privately insured are significantly higher than Medicare and Medicaid rates. The most recent Rand report on hospital price variation found commercially insured patients pay on average 252% more than Medicare for in-patient and out-patient services.

Another way to look at this discrepancy is that Medicare and Medicaid pay somewhat less than the cost of delivering care, while private insurers pay significantly more. The differential in some cases can be as much as ten times higher than government rates.

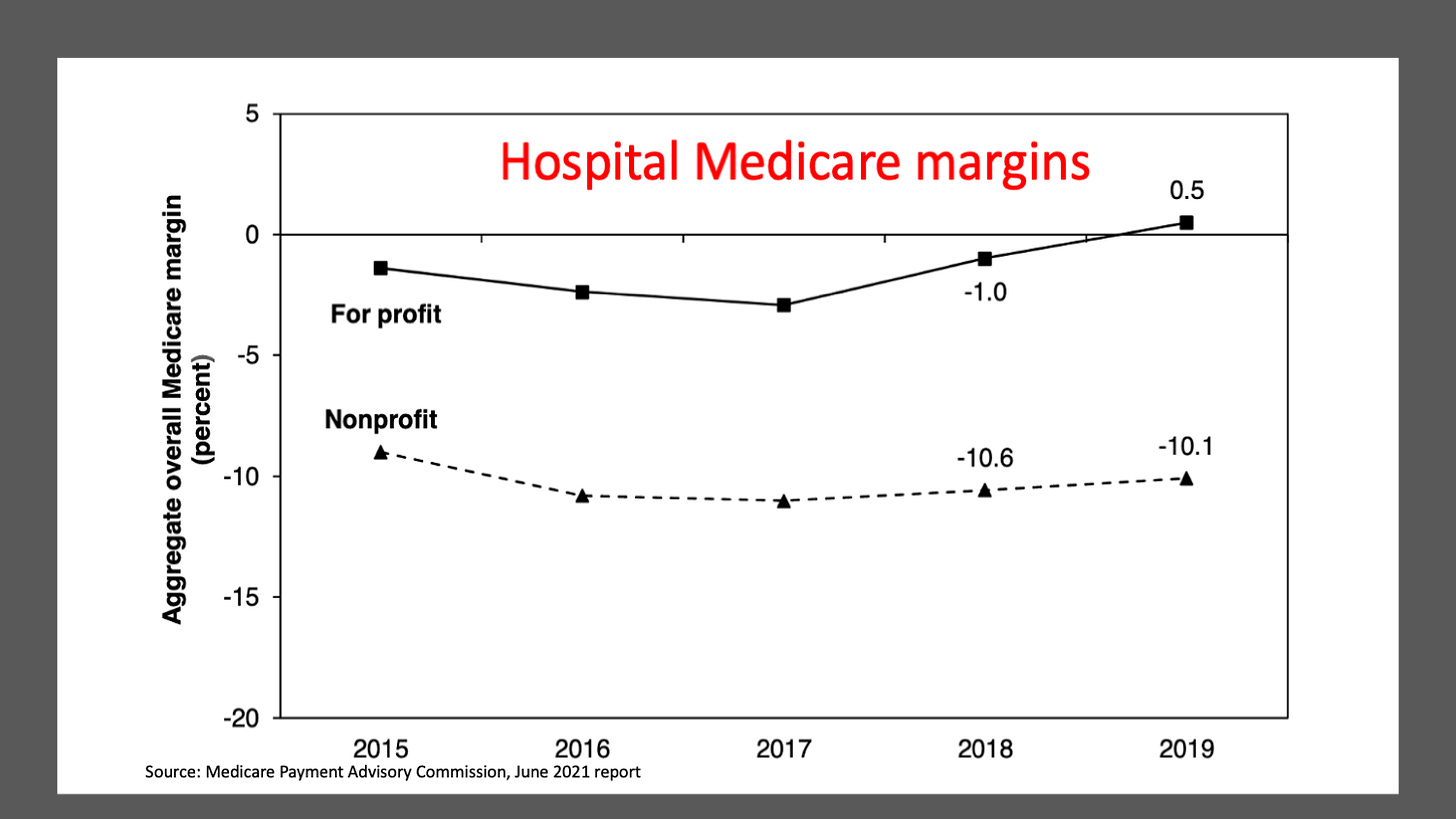

Health care economists enjoy arguing about how much of this difference is due to cost shifting and how much is due to price gouging. I believe the lion’s share of it is due to cost shifting, given that hospital margins even at the most profitable chains rarely exceed 8% and hover around 4% on average in good years (this year, many large chains are showing losses due to the end of federal COVID support amid slumping demand). The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission’s annual report on hospital finances shows Medicare prices at non-profit hospitals, which house about 80% of the nation’s total beds, are about 10% below the actual cost of care.

An enormous amount of administrative overhead (read: waste) is required to maintain this variable pricing system. High-ranking hospital finance officials spend their days negotiating rates with a half dozen or more private insurance plans. These high-paid bureaucrats assure each of their insurer counterparts (equally high-paid) that they are getting a bargain compared to the artificially inflated rack rate, known in the industry as the chargemaster rate. Nobody but the uninsured and occasional Saudi prince pays that.

Insurers gladly accept these rates since it’s not their money, it’s their employer-customers’ money. They have little incentive to fight back since insurer profits, which routinely come in around 5% of the total premium cost, grow larger as the overall tab mounts.

Who are those guys?

To administer this price cornucopia, hospitals’ finance departments must create and maintain separate billing software programs for every insurer, which almost always have multiple plans (PPOs, HMOs, high-deductible plans, Affordable Care Act individual plans, Medicare Advantage; Medicaid managed care; not to mention traditional Medicare and Medicaid). Every one of those plans has different rules, different networks, different co-pays, and different deductibles. Hospitals contract out the job of managing this torrent of data and the associated billing tasks to the dozens of “revenue cycle” firms, a $140 billion industry in the U.S., according to one industry consulting group.

Never heard of the term “revenue cycle”? Neither had I until I became editor of Modern Healthcare a decade ago. At the time, I considered myself an expert in health care. I had no idea how little I knew. I was immediately bombarded by press releases and office visits from rev-cycle firms’ public relations folks hoping to win their clients a positive mention in a trade journal whose audience is primarily made up of high-ranking hospital officials.

To give you a sense of the scale of this massive billing operation, the sub-sector’s revenue amounts to more than 3% of all health care spending in the U.S. That’s one-eighth of the overall cost of administration, which consumes one in four health care dollars in the U.S. and is anywhere from 25% to 100% more than comparable wealthy nations.

Administrative waste isn’t the only downside to this price smorgasbord. The system is inherently unfair, and not just to the employers and their employee families who pay the wildly overpriced commercial rates.

Dominant hospitals in many regions use variable pricing to engage in several market distorting tactics. They offer the largest discounts from the chargemaster rates to dominant insurers and large self-insured employers in exchange for becoming the exclusive or near-exclusive provider in their networks. Small employers and insurers are forced to pay higher rates, often much higher.

Variable pricing also incentivizes hospitals and doctors to locate their operations in communities with lots of commercially insured patients and fewer potential patients on Medicaid or uninsured. This exacerbates the maldistribution of health care facilities, with new hospitals and clinics popping up in well-to-do suburbs while inner cities and rural areas suffer a growing dearth of facilities and services.

A change is needed – but what?

Single-payer advocates have long recognized the inherent unfairness and inequity in variable pricing. But their solution, Medicare for All (M4A), which would achieve uniform pricing through a single government payer, has always run up against three insurmountable political hurdles.

First, providers (hospitals, clinics, and physician offices for the most part) depend on the high prices paid by private insurers to make up for lagging public payer prices (Medicare and Medicaid), which are below the actual cost of care. The idea of switching to universal pricing at Medicare rates is vehemently opposed by most provider organizations.

Second, insurers are vehemently opposed to M4A because it would put them out of business.

And third, most employers are opposed to ending their role in providing health insurance. They earn good will from their employees by offering benefit packages that include health insurance. They also recognize that changing jobs almost always involves changing health plans, which makes it harder for employees to quit, the so-called job lock phenomenon. And, they have a large internal constituency, usually in the human relations department, that works on purchasing plans, explaining benefits, and cooking up wellness programs, which apparently is an acceptable cost given the employee good will and job lock benefits that come from providing coverage.

It's not possible to build a winning political coalition for M4A when providers, payers and employers are arrayed against you. Even Sen. Bernie Sanders’ state of Vermont bumped up against that political reality when it tried to pass a statewide single-payer program in 2014.

The single pricing alternative

Only one state has escaped much of the administrative waste and political downsides of variable pricing. Since the 1970s Maryland has maintained a single-pricing system for the state’s hospitals, where every hospital is required to charge the same price for the same service to every one of its patients, whether they are covered by private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid or are “self-pay,” i.e., uninsured.

All-payer pricing doesn’t mean every hospital charges the same price. It means every payer at any individual hospital pays the same price. Two competing hospitals in the same city can and do have different prices. Prestigious Johns Hopkins Hospital and MedStar’s Union Memorial Hospital, less than four miles apart in Baltimore, charge different prices for the same service.

The prices are set each year by a state regulatory commission that reviews cost and utilization data and approves increases, much the way state utility commissions set electricity and natural gas rates. It uses the same methodology for smaller markets with only one hospital.

A handful of states tried hospital price regulation in the 1970s. All but Maryland repealed those programs in the 1980s in the belief deregulation and competition would solve the rising health care cost problem. The results of that experiment are well known. It did nothing to stop runaway cost growth, consolidation, and vertical integration (buying up physician practices and opening outpatient surgical centers).

Earlier this year, I was part of a four-person team that reviewed the Maryland experience in a two-part series on the Health Affairs website. You can read the wonk’s version of our analysis here and here).

Here’s the short version. In the first few decades of Maryland’s experiment, costs relative to other states fell. But early last decade, Maryland’s system almost failed because hospitals ramped up utilization to offset the slower growth in prices compared to other states. So it added a global budget component to its regulatory scheme.

Prices are now adjusted – even mid-year in some cases – to keep total revenue within a pre-specified annual budget that grows each year at a rate that is less than inflation plus economic growth. In other words, hospitals’ collective share of state economic activity will gradually shrink so long as its all-payer pricing/global budgeting regulations remain in place.

Payment reform requires tax reform

Maryland’s all-payer pricing/global budgeting system has proven highly successful in constraining cost growth in the state. Over the past four decades, Maryland has gone from having hospital costs that were 26% above the national average to 2% below the national average.

In the eight years since Maryland began global budgeting, the program has saved the federal government well over $1 billion compared to Medicare spending in other states. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ analysis, Maryland’s all-payer/global budgeting program saved taxpayers more money than all its other experiments (accountable care organizations; shared savings and bundled payments) that were created by the Affordable Care Act.

But replicating those results in other states will come at a cost. The federal government still pays more for Medicare and Medicaid services in Maryland than it does in other states. Why? Because employers and the privately insured pay less. That’s what happens when you equalize prices.

According to a CMS analysis prepared in 2019, Medicare payment rates per inpatient hospital admission in Maryland were 33 percent to 41 percent higher compared to a comparison group of hospitals in other states. At the same time commercially-insured patients paid prices that were 11 percent to 15 percent lower than what private insurers paid in other states.

Therefore, any move to all-payer pricing must be accompanied by tax reform. The government needs to recapture much of the revenue that employers currently pay for health insurance, which becomes taxable income when their prices are lowered across-the-board.

As any economist will attest, income from reduced premiums are rightfully employee wages (benefits are a form of wages). So, to the extent employers decide to share those gains with their workers (or, in some cases, will immediately lead to higher wages because unions run the health plans), it will lead to higher income tax revenues from individuals. To the extent employers hold onto those funds, it falls directly to their taxable bottom lines.

Using the federal corporate and personal income tax schedules to raise the money needed to move to all-payer pricing is more progressive than relying on employer benefit payments. A simple example will suffice to show how tax reform tied to health care payment reform will help reduce inequality.

Imagine an employer with 500 workers whose salaries (other than a handful of top executives) range from $40,000 a year to $200,000 a year. Every one of those employees is on the company health insurance plan. Let’s further assume each person in the plan costs $20,000 (slightly below the national average for employer-sponsored family plans). For the lowest paid workers at this firm, health benefits represent the equivalent of a 50% boost in wages. For the highest wage workers, it’s just a 10% boost.

That sounds progressive. But now let’s assume that a state moves to all-payer pricing that reduces employer insurance premiums by $5,000 per plan. (The other $15,000 remains a shared employer/employee cost and remains progressively distributed.) Let’s further assume the $5,000 gain is distributed as wages. If done in proportion to costs, the lower paid worker sees his or her salary rise to $45,000 a year, a 12.5% increase. The highest paid workers will see their wages go up to $205,000 a year, a 2.5% increase. Everybody wins, but the lowest paid workers, relatively speaking, win the most.

Since federal taxes are progressive, the higher-paid workers will also pay a larger share of their wage gains in income taxes than the lower-paid workers. If the firm distributes the windfall in proportion to salaries, then the income tax take by the federal government will go up commensurately since the lion’s share of the gains will go to high-wage workers.

The same dynamic would play out on the corporate side. Companies that have older, sicker and therefore more costly to insure employees (think Ford, General Motors, Caterpillar) will get the biggest reduction in premiums. Firms with younger, healthier employees (think Google, Apple, professional service firms) will benefit less. Yet when it comes to recapturing reduced premium revenue through the income tax system, the highly profitable firms will pay more while the money-losing or thin-margin firms will pay less.

In other words, a properly designed tax reform tied to all-payer pricing amounts to a benign form of industrial policy – one that doesn’t rely on picking winners and losers. The redistribution of health care costs is performed in a completely agnostic manner because it relies entirely on the employment marketplace. If you’re a highly profitable Silicon Valley firm with a young, healthy workforce, you’ll pay more of the nation’s health care tab going forward. If you’re a less profitable legacy manufacturing firm in the industrialized Midwest that’s been carrying a disproportionate share of those costs, your burden will be reduced.

Payment reform as delivery system reform

Finally, the all-payer pricing system tied to global budgets has the potential to force major changes in the health care delivery system. All-payer pricing will give Medicaid patients greater access to providers. Global budgets will finally provide hospital systems with an incentive to reorient their internal budgets to providing the primary care, preventive care, home visits and social support that keeps people out of the hospital. If they succeed in reducing total hospitalizations, their ability to raise prices on those who need intensive acute care will generate the funds for the global budget, which can then be spent on providing the ancillary services that reduce overall utilization and lead to a healthier population.

Finally, allowing the global budget to grow slower than overall economic growth allows hospitals and other providers to adjust to providing value-based care over a long period of time. It benefits taxpayers and the economy by freeing up resources to invest in other vital public needs.

As I’ve researched and thought about all-payer pricing reform over the past year, I couldn’t help but wonder why the Maryland model hasn’t drawn more interest from the nation’s employer community. It would allow them to keep employer-based insurance. It makes premiums cheaper for all. Sure, it requires hard-to-enact corporate income tax reform, but there will be far more corporate winners from shifting to increased government funding for health care than there will be losers, all of whom will be highly profitable with relatively low health care costs.

The Senate Health Education Labor and Pensions (HELP) committee, which will be chaired by Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA), should hold hearings next year on allowing other states to experiment with all-payer pricing/global budgeting. I would love to hear a representative cross-section of the nation’s employer community address what they see as the benefits and costs of making the switch.

A Donation to Honor the Vision of Dr. Paul Farmer

Shortly after Paul Farmer helped get Partners in Health off the ground in 1987, international global health groups were debating whether it was even possible to treat poor patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, as its treatments were expensive and required patients to stick to complicated regimens. Indeed, even ordinary tuberculosis for which cheaper drugs and proven regimens existed kept killing poor people around the world.

Farmer, and the band of can-do mavericks who had assembled around P.I.H., had no patience for such excuses — or any excuses for denying care to poor people.

Their programs, based on providing high-quality care regardless of patients’ ability to pay and empowering them in their own treatment, were so successful that they upended global public health.

In his biography of Farmer, “Mountains Beyond Mountains,” from 2003, Tracy Kidder noted that even as tuberculosis killed more adults than any other disease in Haiti, not a single person had died of it since 1988 in the P.I.H. hospital that served a desperately poor rural area with a population of about 100,000 people. Protocols the group developed in Peru for successfully treating multidrug-resistant tuberculosis were adopted globally.

After learning about Farmer and P.I.H. from Kidder’s book, I’ve been donating to the organization ever since.

This year is particularly poignant, though. Farmer died in February.

According to Kidder, P.I.H. reduced newborn H.I.V. transmission from mothers to babies in the rural Haitian community it served to 4 percent, which he also noted was less than the rate in the United States at the time. Their clinic stopped outbreaks of drug-resistant typhoid with effective antibiotics and by cleaning up water supplies. It drastically reduced infant mortality. They achieved this despite a meager budget and with many patients traveling for hours, sometimes on foot or by donkey.

How? Farmer had a very straightforward philosophy: All sick people deserve high-quality treatment. Illness and poverty are intertwined. The proper response is to provide resources while working with people to empower them — thus Partners in Health.

The secret? Treat the whole person. With respect.

Poor patients needed more than drugs to get well, so Partners in Health provided them with food, too. They provided school fees to children. They installed systems to purify the water that caused so much disease. And they always trained and hired local staff, who would follow up with patients to identify and help remove obstacles to their treatment.

Farmer, a Harvard-educated physician, was also trained as a medical anthropologist. Kidder wrote that Farmer learned from local staff that more than three-quarters of Voodoo ceremonies were attempts to drive away illness. He saw little reason to argue with people about beliefs and faith; instead, he always focused on providing high-quality health care. Voodoo priests that he treated ended up as conveyor belts to the clinic, bringing their own ill parishioners to be treated. Farmer approached people with humility and respect, which they reciprocated.

Farmer’s own lapsed Catholicism was rejuvenated by his encounters with liberation theology, with its sharp criticism of inequality and injustice. He didn’t see theology as an obstacle to his mission. He’d say he had “faith” but also add: “I also have faith in penicillin, rifampin, isoniazid and the good absorption of the fluoroquinolones, in bench science, clinical trials, scientific progress, that H.I.V. is the cause of every case of AIDS, that the rich oppress the poor, that wealth is flowing in the wrong direction, that this will cause more epidemics and kill millions.”

Farmer was only 62 when he died, while training staff in a Rwandan hospital he helped establish. He had lived nonstop, treating patients around the world as well as fund-raising, cajoling, pleading and teaching.

Sociologists recognize a form of power called “charismatic authority” — Max Weber called it “the authority of the extraordinary and personal gift of grace.” Farmer certainly represented that. He inspired a generation of doctors, nurses, public health workers and advocates and ordinary people. He used the respect and awe he garnered to lobby global leaders and to help lead the charge to change how public health operates.

But what happens to a movement when its charismatic leader dies? In this case, the best option is what sociologists call “routinization of charisma” — things keep working because they become entrenched and institutionalized, not just because someone extraordinary wields enormous personal influence.

Since the early days, P.I.H. had already grown larger and more institutionalized, attracting millions in donations from individuals as well as foundations. They’ve expanded from Haiti and Peru to places like Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Lesotho and Navajo Nation. But they’re still small compared to the need. And their kind of work is even more crucial now, since the pandemic didn’t just cause suffering through Covid-19 — much basic health care has been interrupted around the world. As it always goes, the poorest, globally, will suffer the most from these disruptions, which will require an extensive effort to ameliorate.

Paul Farmer’s answer to “how does one scale this up” seemed to be simple: follow the basic principles of dignity, training and empowering local people and giving them resources. Money always matters.

Too often, the burning, basic question of lack of resources gets buried under debates about the effectiveness of various approaches and worries about being pragmatic or sensible. But as Farmer pointed out, many who advocate for “sensible” policies that ended up doing too little for the poor and sick “would never accept such a death sentence themselves” or their children.

Would I prefer a global tax policy that redistributed wealth to alleviate poverty and illness, rather than relying on N.G.O.s like P.I.H.? Yes. But we can’t just wait for an ideal resolution when desperate families need a clinic where they will be treated for free, perhaps provided food and school fees.

This year, I’m writing my check for P.I.H. not just because of their good work in some of the toughest places around the world but also with the hope that Paul Farmer’s legacy of providing treatment, respect and empowerment to all patients can endure and even thrive. When one donates online to P.I.H., there’s a box that asks if it’s in memory of someone. I’m going to write Paul Farmer there, and hope they get enough extra donations, maybe even for another clinic somewhere, because saving lives now is what matters.

https://www.blogger.com/blog/post/edit/3936036848977011940/2587380240986496378

No comments:

Post a Comment