Editor's Note -

The following link will take you to a discussion about American health care between Dr. VIvian Lee andShankar Vedantam, the host of the PBS podcast "Hidden Brain".

Pretty interesting.

- SPC

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/02/908728981/slaying-the-fee-for-service-monster-of-american-healthcare

We Know Very Little About America’s Vaccine Debacle

It’s hard to solve a problem when you barely know what’s going on.

by The Editorial Board - NYT - February 7, 2021

A few weeks into her part-time job vaccinating nursing home staff members and residents against the coronavirus, Katherine, a pharmacist, noticed a problem: Roughly 15 to 20 vaccines were being thrown away at the end of each vaccination session. That’s because the number of doses that she and her co-workers had prepared — per the protocol established by Katherine’s manager at CVS, the pharmacy she works for — exceeded the number of people who showed up to be inoculated, often significantly.

Katherine — who asked to be identified by her confirmation name, because she is not authorized to discuss company matters — and her colleagues realized that if they prepared just one or two vials at a time, instead of 20 or more, as they had been doing, they could avoid wasting most doses.

“If you did it one vial at a time as people arrived, you’d never have more than five or six extra shots at the end of any clinic,” Katherine explained to me. “That’s few enough that you could find eligible recipients quickly, so you wouldn’t have to toss any.”

But when Katherine asked her manager at CVS if she and her colleagues could change their protocol, she says he brushed her off. (A spokesman for CVS said that immunizers are instructed not to prepare large numbers of doses at once, and that wait lists are being established at each vaccination site to make use of any extra doses, though Katherine says she has yet to see such a list at the sessions she’s participated in. The spokesman declined to discuss anecdotal reports to the contrary.)

It’s impossible to say whether Katherine’s experience is typical, in part because it’s impossible to say nearly anything with certainty about the nation’s vaccine rollout. Last month Rochelle Walensky, the new director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, reported that owing to failures of planning and monitoring, the federal government has essentially lost track of some 20 million vaccine doses that were delivered to the states during the previous administration.

Part of the problem seems to be a wildly ineffective vaccine management system. As the journal M.I.T. Technology Review has reported, the federal government gave the company Deloitte a $44 million no-bid contract to develop software that all states could use to manage their vaccine rollouts. The resulting product is so unreliable that many health departments have abandoned it. Other troubles abound. As noted by ProPublica, many states have not required health facilities to report vaccine waste, despite being asked to do so by the C.D.C.

If we don’t know where shots have gone, how can we possibly know what portion have been lost, discarded or even stolen? And if we don’t know where or how or why such waste is occurring, how can we possibly hope to minimize it?

The same goes for vaccination equity. We know that the 32 million or so shots that have been administered so far have gone disproportionately to wealthier, whiter Americans. But we don’t know exactly how bad those disparities are — only about half of all vaccinations logged so far include racial data — and we don’t know what’s behind that gap. Some people blame the inequity on vaccine hesitancy in marginalized communities; others point to online registration systems and clinic hours that make shots more difficult to access for low-income Americans. Each of those problems has different solutions.

Vaccines are not the only thing officials are in the dark about. They also don’t know where or how fast mutant variants of concern are spreading. The C.D.C. is now aiming to sequence the genomes of some 6,000 virus samples every week. That’s a big improvement over how things have been going. But it’s not nearly enough to get a handle on the crisis. In some states, just a tiny fraction of cases are being sequenced, even during large outbreaks that might be explained by more transmissible variants. In North Dakota, for example, hundreds of new cases were logged and scores of people died during a sudden spike in cases last fall. But just 33 coronavirus genomes were uploaded to GISAID, the global repository of coronavirus sequences during that time.

It’s tempting to attribute every failure of pandemic response to the previous administration. It has much to answer for. But the new administration — and the country — will have to grapple with problems that predate former President Donald Trump’s time in office. In the long term, a comprehensive overhaul of the nation’s disease surveillance system, a massive upgrade of its data infrastructure and a reimagining of public health authority during a global crisis are all in order.

In the short term, Congress should pass the full coronavirus spending package laid out by President Biden, which would boost funding for the vaccine rollout, and should strongly consider the Tracking Covid-19 Variants Act, which would do the same for genomic surveillance.

The Biden administration also should re-evaluate its arrangement with Walgreens and CVS, established under the Trump administration, to vaccinate long-term care facilities. The program managed to vaccinate more than two million people by late January, but its success has been uneven and tempered with troubles, and some states appear to have done better by opting out. At the very least, much more oversight and accountability are needed, as Katherine’s story suggests.

The C.D.C. should also re-examine its contracts with Deloitte, and in the meantime should call loudly on all states to do two things: ramp up their genome sequencing efforts — ideally in collaboration with the agency — and require that vaccine waste be rigorously monitored and consistently reported. Federal health officials don’t have the authority to mandate either action, but they do have a powerful platform for exposing these gaps and helping to close them, especially now that they have been unmuzzled.

These measures, taken together, could help bring the nation much closer to its ultimate goal of routing this pandemic at last.

Grim as things sound, there is great reason to hope right now. More vaccines are coming, and case counts and death counts are finally leveling off. There’s a good chance that children will return to school come fall and that people across the country will be able to celebrate holidays in normal fashion by next winter. But the nation remains locked in a desperate contest, between its own ability to vaccinate people as quickly as possible and the virus’s ability to mutate and spread ever faster. Right now, the virushttps://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/07/opinion/covid-vaccines-mutations.html?

POLL: Medicare Advantage Beneficiaries are Highly Satisfied with Their Coverage and Eager to Protect It

Allyson Y. Schwartz - Health Affairs - February 9, 2021

Even as health care workers and other essential personnel worked feverishly to meet the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic, too often, the story has been one of personal loss, shared disappointment and uncertainty, and failure of our systems and institutions.

With more than 450,000 Americans dead, it is not a partisan statement to observe that something went deeply wrong. Even today, hospitals remain overwhelmed, long awaited vaccines are in short supply, and too many of our fellow Americans do not properly wear masks despite the overwhelming evidence of their value as a tool in fighting this virus. Recently, President Biden rightly warned, “It’s going to take months for us to turn things around.”

Yet amid the failures of COVID-19, a scientific poll of more than 1,200 seniors points to an area of health care that has shown success: Medicare Advantage.

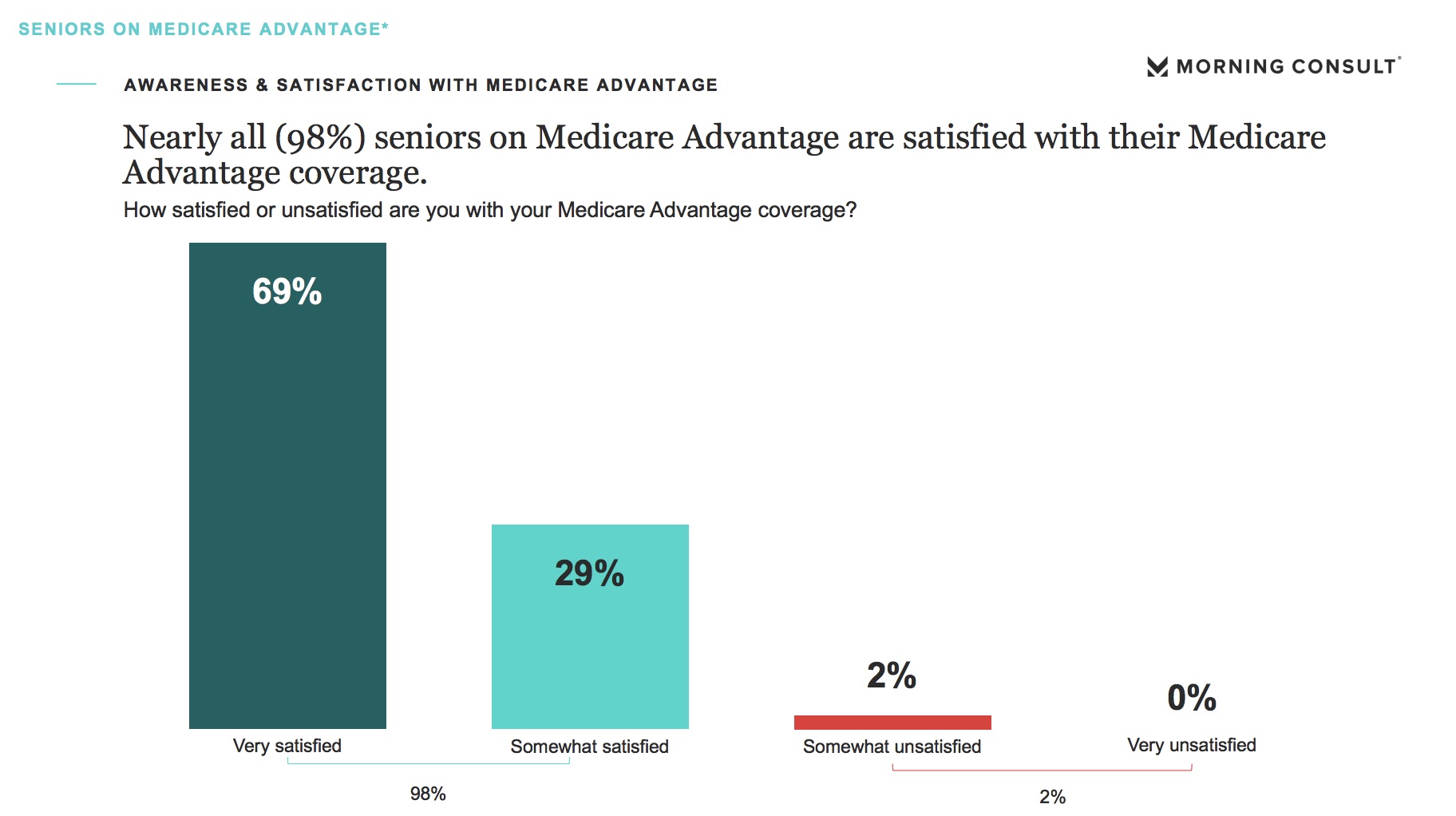

The survey data gathered by pollsters at Morning Consult in late December – more than nine months into the thick of COVID-19 – shows that overall Medicare Advantage satisfaction grew during the public health emergency; reaching a near-universal 98 percent, as compared to 94 percent in a late 2019 poll.

In addition, 98 percent of respondents expressed satisfaction with their Medicare Advantage plan’s handling of COVID-19, and 97 percent were satisfied with their Medicare Advantage network of physicians, hospitals, and specialists—even in the midst of the pandemic.

At first glance, increased satisfaction with one’s health care coverage in a global health crisis is surprising. Maybe it shouldn’t be.

While health care costs elsewhere rise, Medicare Advantage premiums for 2021 are at their lowest level since 2007. What’s more, research commissioned by the Center for Innovation in Medicare Advantage demonstrates how, when COVID-19 hit, Medicare Advantage was better suited to adapt quickly to telehealth. Today, four in 10 Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have used telehealth to see their doctor during the public health emergency, and 91 percent are satisfied with their experience.

Moreover, consumers have seen Medicare Advantage step up to the challenges of COVID-19 by waiving costs, donating to aid and recovery efforts, providing meal deliveries, continuing home visits for the most complex patients, and reaching out to individuals who were alone and worried.

Medicare Advantage providers maintained contact with beneficiaries with chronic conditions, working to be sure that they received the care they needed so deferred care would not mean worsening health status. Some health plans even sent care packages to seniors with items like masks, hand sanitizer, and other resources to stay healthy and safe. It’s no wonder, then, that the percentage of seniors who say its important to have a choice other than Traditional Medicare has risen to an all-time high of 95 percent.

All told, this polling data shows that, when crisis struck, Medicare Advantage was ready. In a health care emergency that has laid bare deep, persisting challenges in care delivery, we saw beneficiaries’ satisfaction with Medicare Advantage reach new heights. This extends to minority beneficiaries, too.

Satisfaction with Medicare Advantage among nonwhite beneficiaries in our poll reached 99 percent, indicating a level of trust between beneficiaries and providers that is critical to efforts to address racial inequities in health care.

Importantly, this poll also showed that Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are motivated and ready to protect the care and coverage on which they have come to depend.

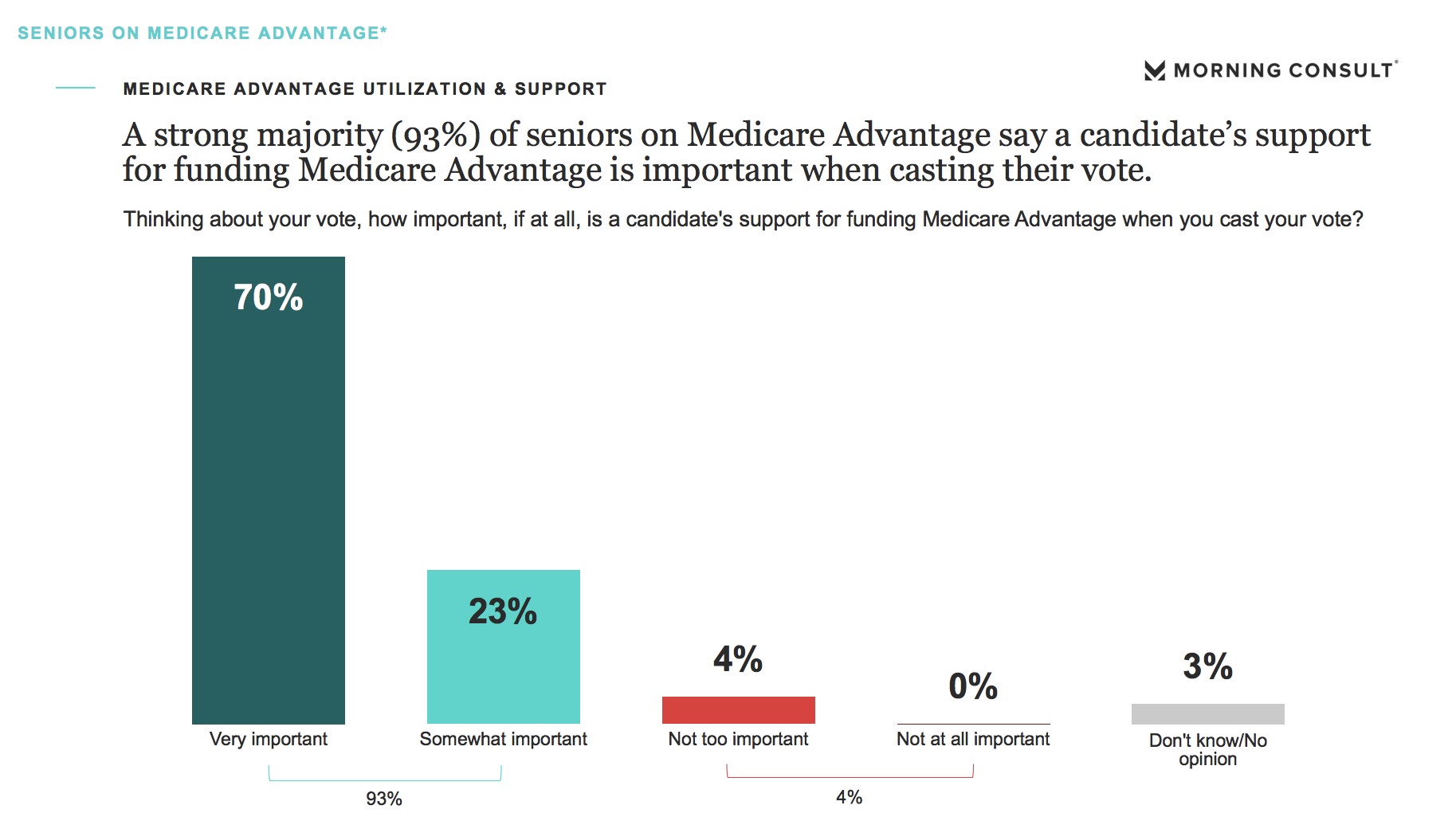

93 percent of seniors on Medicare Advantage now say a candidate’s support for Medicare Advantage is important to their vote, including 70 percent who identify this as “very important.” Further, more than three-quarters of beneficiaries – 77 percent – say they would be “strongly opposed” to any proposed cuts to Medicare Advantage.

The numbers don’t lie. Medicare Advantage works for consumers who overwhelmingly give it their strong support and approval.

As the new Congress and administration looks to their next steps in health care policy, protecting and strengthening the coverage and care that more than 40 percent of Medicare beneficiaries actively choose is a great place to start. Medicare Advantage is a public-private partnership that not only works for those enrolled today but is leading the way in modernizing health care for the future.

Allyson Y. Schwartz is President and CEO of Better Medicare Alliance and a former Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, serving from 2005-2015.

https://www.healthaffairs.org/sponsored-content/value-of-medicare-advantage-6?

Disease experts warn of surge in deaths from Covid variants as US lags in tracking

Despite having a well-developed genomic sequencing infrastructure, a national surveillance program was never enacted

by Jessica Glenza - The Guardian - February 8, 2021

Experts who have spent the last year forecasting Covid-19 transmission across the US are now considering scenarios for the spread of new, more infectious strains of the coronavirus.

At the same time, the US continues to lag in surveillance for coronavirus variants, despite having among the most well developed genomic sequencing infrastructure in the world.

The warnings come as the US appears to have crested a devastating winter wave of infections, which at one time saw more than 300,000 new infections and 4,000 deaths a day. Even though daily infections have more than halved from the peak, with death rates expected to drop soon also, the threat of the more infectious variants now has some considering the possibility of a fresh surge.

“It’s a grim projection, unfortunately,” said Ali Mokdad, professor at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, one of the leading academic forecasters of Covid-19. “I’m concerned about a spike due to the new variant and the relaxation of social distancing,” he said. “People are tired. People are very tired.”

Forecasters still do not consider this the most likely scenario, though also not the worst-case scenario, but the addition of the model is a recognition of how dangerous new variants can be, even in an environment where hospitalization and death rates are expected to decline.

IHME’s “rapid variant spread” model predicts total deaths could increase by 26,000 over the most likely scenario by May. Such a forecast would result in a total of more than 620,000 Covid-19 deaths by that time.

Notably, the most accurate are often “ensemble” forecasts, which draw in many individual projections. The ensemble forecast published by the CDC makes a prediction only through 27 February, when it estimates up to 534,000 deaths could occur. IHME also estimates universal masking could save 31,000 lives.

The most well understood variant of concern is the B117 strain, first detected in the United Kingdom. B117 is believed to be as much as 50% more transmissible and to be now circulating in the US, where 541 cases have been found in 33 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Studies are still being conducted on how B117 may impact the effectiveness of the two vaccines currently authorized in the US, from Moderna and Pfizer. Another variant from South Africa, called B1351 and recently found in South Carolina, does appear to reduce vaccine efficacy. New strains can also impact the effectiveness of some of the only treatments for Covid-19 patients, including monoclonal antibodies.

“If the new variant makes the vaccines less effective and new variants come up, we could have a surge in the summer,” said Mokdad.

Variations in how a virus replicates genetic materials are expected and a feature of how viruses evolve over time. This can be especially true of viruses like the coronavirus, whose genetic material is made of ribonucleic acid (RNA), because these viruses lack some “proofreading” mechanisms that reduce mutations. Most changes are benign – like a typo in a paper – and do not change the functionality of the virus.

But rampant, widespread global transmission has given the coronavirus millions upon millions of chances to replicate, and change as it does. Among the random, inconsequential typos, are rare changes that alter how the virus behaves.

For example, B117 is believed to be more infectious. A more infectious virus is a more successful virus, and through thousands of new infections, natural selection will favor the successful virus, eventually replacing previous, once dominant strains.

“A small percentage of a big number is still a big number,” said Emily Bruce, a virologist and investigator at the Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease at the University of Vermont’s Larner College of Medicine. Variations are “a function of the number of people and number of infections and cycles of replication the virus is going through”.

Scientists can detect these changes using next generation sequencing technology. This technology was used in spring 2020 to show the origin of a majority of Covid-19 cases in New York were actually from Europe, not China as the Trump administration insisted.

While some labs were pursuing specific projects using this technology, a national, systematic surveillance program was never put in place. It wasn’t until November that the CDC began regularly receiving samples from Covid-19 patients from state labs. It now processes roughly 750 samples a week. The US currently ranks 43rd in the world for Covid-19 genomic sequencing, despite having well developed genomic sequencing infrastructure.

“There’s people who’ve done spectacular work here, but it wasn’t funded and strategized in a national way the way leaders in the field did this,” said Bruce.

The cost of genomic sequencing has dropped precipitously since the early 2000s, when ambitions to map the human genome cost $100m, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute. Today, sequencing one human genome costs about $1,000.

Doctors hoped to start using this advanced technology, called next generation sequencing, to tailor treatment to specific patients. That field is touted as “precision medicine”, a way for doctors to tailor treatments to specific patients.

But, as in many other aspects of American life, the coronavirus pandemic has revealed weaknesses in the system. Experts said, in large part, the lack of a national surveillance program for coronavirus variants came down to lack of funding.

“It costs a certain amount of money to sequence each strain, and I am a brand new investigator, I don’t have the money to pay for that,” said Bruce. “And people’s insurance isn’t going to pay for that because it’s important information, but it’s not going to change an individual patient’s care.”

Sequencing an RNA virus is less expensive than sequencing a whole human genome, because they are far less complex organisms, but it is still far more expensive than a typical coronavirus test, running in the hundreds of dollars. That is because expert labor is needed to interpret the results – including molecular biologists and virologists like Bruce.

“This virus is here to stay,” said Mokdad. “We’re not going to reach herd immunity, simply, we’re not going to reach it. It’s going to be seasonal, and it’s going to be like the flu, and we’re going to need to be ready for it,” he said.

That leads to another potential need from vaccine-makers – vaccine updates to enhance immunity to new variants. Already, Moderna and Pfizer are working on “booster shots” for Covid-19 variants. Experts now recommend double-masking to protect against the virus, alongside more vigilant social distancing.

Together, these developments have made Mokdad certain of one outcome: “I’m 100% sure in winter [2021-22] we will have a surge – but it will slow down our decline. But I’m convinced it will happen.”

How Rich Hospitals Profit From Patients in Car Crashes

Hospitals use century-old lien laws to bypass insurers and charge patients, especially poorer ones, the full amount.

Sarah Kliff and - NYT - February 2, 2021

When Monica Smith was badly hurt in a car accident, she assumed Medicaid would cover the medical bills. Ms. Smith, 45, made sure to show her insurance card after an ambulance took her to Parkview Regional Medical Center in Fort Wayne, Ind. She spent three days in the hospital and weeks in a neck brace.

But the hospital never sent her bills to Medicaid, which would have paid for the care in full, and the hospital refused requests to do so. Instead, it pursued an amount five times higher from Ms. Smith directly by placing a lien on her accident settlement.

Parkview is among scores of wealthy hospitals that have quietly used century-old hospital lien laws to increase revenue, often at the expense of low-income people like Ms. Smith. By using liens — a claim on an asset, such as a home or a settlement payment, to make sure someone repays a debt — hospitals can collect on money that otherwise would have gone to the patient to compensate for pain and suffering.

They can also ignore the steep discounts they are contractually required to offer to health insurers, and instead pursue their full charges.

The difference between the two prices can be staggering. In Ms. Smith’s case, the bills that Medicaid would have paid, $2,500, ballooned to $12,856 when the hospital pursued a lien.

“It’s astounding to think Medicaid patients would be charged the full-billed price,” said Christopher Whaley, a health economist at the RAND Corporation who studies hospital pricing. “It’s absolutely unbelievable.”

The practice of bypassing insurers to pursue full charges from accident victims’ settlements has become routine in major health systems across the country, court records and interviews show. It is most lucrative when used against low-income patients with Medicaid, which tends to pay lower reimbursement rates than private health plans.

In a memo that surfaced in 2014 litigation, a hospital in Washington State estimated that this practice generated $10 million annually.

As part of its check-in process, a Catholic hospital in Oklahoma offers some accident victims a waiver to sign stating they do not want their health plan billed for care. One patient received the waiver shortly after a car accident in which her head hit the windshield. She said she had no recollection of signing the document, but faced a $34,106 lien as a result.

“The way they are spinning it is, you don’t want to use your health insurance because someone else caused this,” said Loren Toombs, an Oklahoma trial lawyer who represented the patient. “It’s clearly a business tactic and a huge issue, but it’s not always illegal.”

Hospitals have come under scrutiny in recent years for increasingly turning to the courts to recover patients’ unpaid bills, even in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. Hospitals, many of which received significant bailouts last year, have used these court rulings to garnish patients’ wages and take their homes.

But less attention has been paid to hospital lien laws, which many states passed in the early 20th century, when fewer than 10 percent of Americans had health coverage. The laws were meant to protect hospitals from the burden of caring for uninsured patients, and to give them an incentive to treat those who could not pay upfront.

A century later, hospital liens are most commonly used to pursue debts from car accident victims. The practice can be so lucrative, documents and interviews show, that some hospitals use outside debt collection companies to scour police records for recent accidents to make sure they identify which of their patients might have been in a wreck, so that they can pursue them with liens.

Some laws limit what share of a patient settlement a hospital can lay claim to, and others allow only nonprofit hospitals to collect debts this way. Certain states require hospitals to bill accident victims’ health plans rather than using a lien. This approach is seen as more consumer-friendly because patients benefit from the discounts that health plans have negotiated on their behalf.

Five Weeknight Dishes: Fresh dinner ideas for busy people who want something great to eat.

“If there is a patient that has viable coverage from multiple sources, it would be a reasonable position to seek payment from whoever is going to pay more,” said Joe Fifer, chief executive of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, a trade group of hospital financial officers.

Mr. Fifer said that state and federal laws often dictate which insurer should be billed, and that hospitals regularly must navigate between health and auto insurers that claim the other is responsible. He advises member executives to be clear at the outset with patients about how the lien process works.

“I feel sorry for patients in these situations,” Mr. Fifer said.

Going after widows and veterans

When states have permissive hospital lien laws, some hospitals take advantage in ways that hurt patients. These hospitals tend to be wealthier, The New York Times found, and many of those that received hundreds of millions of dollars in federal bailout funding during the pandemic are among the most aggressive in pursuing payment through hospital liens.

Community Health Systems, which owns 86 hospitals across the country, received about a quarter-billion in federal funds during the pandemic, according to data compiled by Good Jobs First, which researches government subsidies of companies.

One of its hospitals in Tennessee refused to bill Medicare or the veterans health insurance of Jeremy Greenbaum after a car crash aggravated an old combat wound to his ankle. Instead, the hospital filed liens in 2019 for the full price of his care, records show.

“I could cut off a finger and the V.A. would cover it,” Mr. Greenbaum said, adding “the insurance is just that good.” The worst part, Mr. Greenbaum said, was the nearly constant collection calls that made him feel like a “real deadbeat.” Mr. Greenbaum is now part of a lawsuit against the hospital, Tennova Healthcare Clarksville, that accuses it of predatory lien practices.

Ann Metz, a spokeswoman for Tennova, said that “Tennessee state law allows hospitals to file provider liens as a way to ensure that health care providers can be paid for treatment.”

The practice of bypassing insurers to pursue full charges from accident victims’ settlements has become routine in major health systems across the country, court records and interviews show. It is most lucrative when used against low-income patients with Medicaid, which tends to pay lower reimbursement rates than private health plans.

In a memo that surfaced in 2014 litigation, a hospital in Washington State estimated that this practice generated $10 million annually.

As part of its check-in process, a Catholic hospital in Oklahoma offers some accident victims a waiver to sign stating they do not want their health plan billed for care. One patient received the waiver shortly after a car accident in which her head hit the windshield. She said she had no recollection of signing the document, but faced a $34,106 lien as a result.

“The way they are spinning it is, you don’t want to use your health insurance because someone else caused this,” said Loren Toombs, an Oklahoma trial lawyer who represented the patient. “It’s clearly a business tactic and a huge issue, but it’s not always illegal.”

Hospitals have come under scrutiny in recent years for increasingly turning to the courts to recover patients’ unpaid bills, even in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. Hospitals, many of which received significant bailouts last year, have used these court rulings to garnish patients’ wages and take their homes.

But less attention has been paid to hospital lien laws, which many states passed in the early 20th century, when fewer than 10 percent of Americans had health coverage. The laws were meant to protect hospitals from the burden of caring for uninsured patients, and to give them an incentive to treat those who could not pay upfront.

A century later, hospital liens are most commonly used to pursue debts from car accident victims. The practice can be so lucrative, documents and interviews show, that some hospitals use outside debt collection companies to scour police records for recent accidents to make sure they identify which of their patients might have been in a wreck, so that they can pursue them with liens.

Some laws limit what share of a patient settlement a hospital can lay claim to, and others allow only nonprofit hospitals to collect debts this way. Certain states require hospitals to bill accident victims’ health plans rather than using a lien. This approach is seen as more consumer-friendly because patients benefit from the discounts that health plans have negotiated on their behalf.

Five Weeknight Dishes: Fresh dinner ideas for busy people who want something great to eat.

“If there is a patient that has viable coverage from multiple sources, it would be a reasonable position to seek payment from whoever is going to pay more,” said Joe Fifer, chief executive of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, a trade group of hospital financial officers.

Mr. Fifer said that state and federal laws often dictate which insurer should be billed, and that hospitals regularly must navigate between health and auto insurers that claim the other is responsible. He advises member executives to be clear at the outset with patients about how the lien process works.

“I feel sorry for patients in these situations,” Mr. Fifer said.

Going after widows and veterans

When states have permissive hospital lien laws, some hospitals take advantage in ways that hurt patients. These hospitals tend to be wealthier, The New York Times found, and many of those that received hundreds of millions of dollars in federal bailout funding during the pandemic are among the most aggressive in pursuing payment through hospital liens.

Community Health Systems, which owns 86 hospitals across the country, received about a quarter-billion in federal funds during the pandemic, according to data compiled by Good Jobs First, which researches government subsidies of companies.

One of its hospitals in Tennessee refused to bill Medicare or the veterans health insurance of Jeremy Greenbaum after a car crash aggravated an old combat wound to his ankle. Instead, the hospital filed liens in 2019 for the full price of his care, records show.

“I could cut off a finger and the V.A. would cover it,” Mr. Greenbaum said, adding “the insurance is just that good.” The worst part, Mr. Greenbaum said, was the nearly constant collection calls that made him feel like a “real deadbeat.” Mr. Greenbaum is now part of a lawsuit against the hospital, Tennova Healthcare Clarksville, that accuses it of predatory lien practices.

Ann Metz, a spokeswoman for Tennova, said that “Tennessee state law allows hospitals to file provider liens as a way to ensure that health care providers can be paid for treatment.”

Multiple lawyers identified the WellStar Health System in the Atlanta area as another that frequently pursued liens against patients.

Dennis Denson, a 53-year-old logistics manager, was treated at a WellStar hospital for injuries he sustained after being rear-ended three years ago. Mr. Denson said he presented his health insurance card as soon as he got to the emergency room. But he is still fighting with the hospital, which, unlike the ambulance provider, didn’t bill his health insurance. Instead, the hospital placed a $13,469 lien against his auto accident settlement.

For Mr. Denson, the lien is like a cloud hanging over his recovery. To cover his ensuing bills — the cost of a replacement car; the chiropractic treatment; everyday expenses after a stint out of work — he had to go into debt.

“I really feel angry,” Mr. Denson said. “You are going into a fight with the hospital that you don’t know the rules of.”

A WellStar spokeswoman said the hospital uses liens only when privately insured patients don’t provide coverage. The hospital and Mr. Denson disagree on when proof of coverage was provided: He recalls giving it at the emergency room, while the hospital says it was not given until more than a year after the accident.

Such liens can torpedo patients’ credit scores and leave them unable to pay for needed follow-up care.

Mary Edmison, an 86-year-old widow, said she tried everything to get Mary Washington, a hospital in Fredericksburg, Va., to bill her insurance — Medicare and private coverage — for the treatment she received in a 2016 crash. She called; she went to the hospital’s billing department; she sent a handwritten letter.

“Again and again, I’ve asked Mary Washington to send their bills through the proper channels,” she wrote in a 2017 letter. “I don’t know what their problem is.”

In August 2017, the hospital sued her for more than $6,000. Ms. Edmison, who has since settled the issue with the help of a lawyer, was shocked. “I’m on a fixed income and those kind of charges would have sunk me,” she said.

Eric Fletcher, a spokesman for Mary Washington, declined to comment on Ms. Edmison’s case but said the hospital complies with state and federal lien laws. “We never want a patient to endure hardship related to medical bills,” he said.

Arguing that ‘Medicaid is not insurance'

In the early 2010s, Indiana legislators passed a law that required hospitals to bill insured patients’ coverage before pursuing additional debts with a lien.

The legislation initially specified Medicare, Medicaid and private health plans as those that had to be billed. At the last minute, Medicaid was taken out. Supporters of the new law paid little attention to the change, assuming that legislation requiring hospitals to bill “health insurance” would suffice.

The Parkview Hospital system, a nonprofit in Fort Wayne, Ind., saw things differently. Parkview was already known for having the second-highest health care prices in the country. Multiple trial lawyers in Indiana have identified it as the most aggressive hospital when it comes to liens.

Even after the lien reform, the hospital continued to bypass Medicaid patients’ coverage and pursue its full-billed charges. Liens challenged in court, ranging from $307 to $117,272, most likely represent a small fraction of those filed against patients.

“Other hospitals don’t do this — they abide by the law,” said David Farnbauch, a trial lawyer who has sued Parkview over its lien practices.

Parkview has faced at least nine lawsuits over liens related to Medicaid. It has filed counterclaims against at least one patient, tacking interest and attorney fees onto the outstanding debt.

When Ms. Smith and other Medicaid beneficiaries sued Parkview over their liens this summer, the hospital responded by arguing that Medicaid is “government assistance” and not health insurance, thus not covered under the new lien law.

“Parkview denies that Medicaid coverage is insurance,” the hospital argued in a June 2020 legal brief.

The hospital contended that patients should be held accountable for their medical bills rather than relying on the government. “By forcing hospitals like Parkview to submit its charges to the state-administered Medicaid program, the court will ignore the public policy goals of holding individuals responsible for their actions,” Parkview argued.

Judge Craig Bobay said he noticed “a lot” of these cases coming into his courtroom in 2019 making the same arguments.

He rejected Parkview’s claims last summer, finding that “Indiana plainly defines the term Medicaid as ‘health insurance.’”

“Before filing a hospital lien, Parkview must first reduce its bill by the amount of benefits to which a patient is entitled under the terms of medical insurance, including Medicaid,” he wrote.

Parkview Hospital declined an interview for this article but provided a statement from its chief legal officer, David Storey. He said the health system no longer filed liens against Medicaid patients. “Parkview has always taken a conservative and fair approach to collections,” he said.

Ms. Smith received her full settlement in 2020, nearly four years after her accident.

“At first I thought it was a registration error, but shame on them for basically trying to get more money out of the situation,” she said. “It felt like, what is even the point of having health insurance if you won’t bill it?”

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/01/upshot/rich-hospitals-profit-poor.html?

Burned by Low Reimbursements, Some Doctors Stop Testing for Covid

Some insurers pay pediatricians less than the cost of the test itself, jeopardizing a tool to help control the pandemic.

by Sarah Kliff - NYT - February 3, 2021

Dr. Robin Larabee was thrilled to start offering coronavirus testing at her pediatrics practice in Denver last fall. Testing for children is often scarce, and her new machines could return results within minutes.

She quickly discovered an unexpected obstacle: a major health insurer that paid her less than the cost of the test itself. Each kit Dr. Larabee purchased for her machines cost about $41, but the insurer sent back half that amount each time she submitted a claim.

Across the country, some doctors are seeing reimbursement rates so low that they do not cover the cost of the test supplies, jeopardizing access to a tool experts see as crucial to stopping the virus’s spread. “I’ve gone up the food chain, and gotten as far as I can, and they just tell me this is the rate,” she said.

She doesn’t use her new machines for that health plan’s enrollees anymore, instead sending their tests to an outside laboratory. That extra step means results take days rather than minutes to come back.

“All I did this summer was look at spreadsheets to figure out how much this would cost,” she said. “In 15 years of practice, this is the first time I’ve ever had to consider altering my care for a certain population.”

With new variants of coronavirus emerging, experts say testing will be especially important. But the low fees have led some doctors to stop testing certain patients, or to forgo testing altogether. The problem of low reimbursement rates appears to be most common with pediatricians using in-office rapid testing.

“We are not doing Covid testing because we cannot afford to take the financial hit in the middle of the pandemic,” said Dr. Suzanne Berman, a pediatrician in Crossville, Tenn. Her clinic serves a low-income Appalachian community where coronavirus is now spreading rapidly, and 17 percent of tests are coming back positive as of this week.

Rapid in-office tests are less sensitive than those sent off to a lab, which means they miss some positive cases. Researchers are still learning about the efficacy of these tests in children. Still, infectious disease experts say fast turnaround tests are important in controlling the pandemic, particularly in areas where other types of testing are less available.

“We definitely need to have these tests covered,” said Sam Dominguez, medical director of the microbiology lab at Children’s Hospital Colorado. “If they come up positive, you have an answer right away and can go ahead and do the appropriate isolation.”

Across the country, multiple doctors identified UnitedHealthcare and certain state Medicaid plans as the ones that routinely pay test rates that do not cover the cost of supplies.

Medicaid and Medicare often pay lower prices than private insurers do. But the reimbursements from a large private insurer like UnitedHealthcare came as a shock to doctors.

A spokesman, Matthew Wiggin, said that UnitedHealthcare was not underpaying for coronavirus testing, and that its rates were consistent with those of other health plans.

“We want to make sure every member has access to testing and encourage any provider with payment questions to contact us so we can resolve their concerns,” he said in a statement.

Doctors who have complained to UnitedHealthcare and other health plans, however, say they’ve been offered little recourse. One was told it wasn’t an issue that any other doctor had raised. Another was directed to find a supplier with a lower price.

Many private insurers have prospered during the pandemic, with Americans delaying much medical care in 2020. As of September, insurers’ monthly profit margins on large-group health plans were up 24 percent.

This month, Minnesota-based UnitedHealthcare reported earning a $15.4 billion profit last year, up from $13.8 billion in 2019. In its 2020 financial review, it projected that costs of coronavirus testing would have an “unfavorable” impact on this year’s share price.

In mid-January, the American Academy of Pediatrics informed UnitedHealthcare of the problem its members have faced. It’s still awaiting a response. The California Medical Association has also raised the issue.

With other health services, doctors usually have a way to recoup losses when they believe insurer payments are not high enough: They can bill the patient directly for the remaining balance.

But when it comes to coronavirus testing, federal law prohibits that. Legislation passed last spring tried to make coronavirus testing free for patients by barring providers from billing patients for the test. It requires insurers to fully cover the cost of the test but does not define what constitutes a “complete” reimbursement.

Pediatricians provide much of the testing infrastructure for American children. Many large testing sites run by health departments and pharmacies do not test children, even though demand for pediatric testing is expected to rise as more students return to in-person school.

Dr. Bob Stephens runs a solo pediatrics practice in Seguin, Texas. About 60 percent of his patients are Hispanic, and 50 percent of his patients are covered by the state Medicaid program.

He began offering rapid coronavirus testing in October, buying each kit for $37, but learned the plans covering his Medicaid patients paid only $15 to $19.

He did a bit of digging: Texas farms out its Medicaid program to private insurers known as managed care organizations. For nearly all of last year, the state did not set reimbursement rates for in-office testing. Instead, it let private insurers decide what they wished to pay.

At the end of December, Dr. Stephens decided to stop offering the rapid test to Medicaid patients and to provide it only to those with private insurers, whose plans typically paid $45 to $50.

“It’s difficult for me ethically, because I like to treat everyone the same,” he said. “I have a problem having to not offer things to people when, in my medical judgment, they’re deserved.”

Aetna runs one of the Medicaid plans that serve Dr. Stephens’s patients. A spokesman confirmed that it had paid doctors $15 for coronavirus tests last year, but said it was increasing its fee to $37.79 after receiving updated guidance from the state in recent weeks.

Providers elsewhere are using up the tests they have already purchased, regardless of a patient’s insurance, taking some losses.

“I feel torn between my obligation and my desire to have patients see me, and my ability to stay in business,” said Dr. Reshma Chugani, a pediatrician in the Atlanta area. She has found that most insurers fully cover the test, but UnitedHealthcare — the insurer for about a quarter of her patients — typically reimburses 60 percent.

Her practice sustained a 20 percent loss last year and still has low patient volume. Some parents have put off wellness checks, and fewer children in school means fewer sick visits. She has furloughed some staff members and asked others to work reduced hours because of the decreased revenue.

“It feels like a lose-lose situation,” she said. “I could say no to testing, and drive my patients away. Or I can say yes, and keep operating at a loss.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/03/upshot/covid-testing-children-pediatricians.html?

Editor's Note -

After you've read the preceding article, go to the NYT website (click on the link above) and read the comments.

-SPC

Column: Save millions by cutting administrative waste in health care

Hawaii is facing a projected $1.4 billion budget shortfall for the coming fiscal year, with talk of cuts in vital government services and higher taxes. Instead, if the state reformed financing of state employee health benefits and Medicaid, around $850 million a year could be recovered to fill that shortfall.

Prior to the pandemic, health care costs were about 30% of the nearly $8 billion state budget: about half EUTF (Employer-Union Trust Fund) health benefits for state employees and half Medicaid. Medicaid enrollment has increased 20% due to the pandemic, so Medicaid is now about 20% of the budget.

Both EUTF health benefits and Medicaid contract with health insurance plans to accept full insurance risk. Most other states have already moved to self- insure employee health benefits, with the state becoming the insurer and contracting with a health insurance company for Administrative Services Only (ASO).

With full-risk contracts, health insurance plans always charge enough to assure they are very unlikely to lose money, increasing cost. ASO contracts typically reduce administrative costs by two thirds or more compared to full- risk contracts, and also give the state more control over health program design, instead of letting insurance companies do whatever they want.

For example, HMSA has forced the “value-based payment” (VBP) policy fad onto Hawaii’s primary care doctors, resulting in increased cost, and Medicaid plans to follow suit. But VBP is widely blamed as a major cause of Hawaii’s doctor shortage and for discouraging doctors from starting new practices in Hawaii.

|

A 2013 Hawaii law requires the state to pre-fund future health benefits, and current payments are about $500 million a year, with over $11 billion in remaining unfunded future liabilities. Bills introduced for the 2021 Legislature would convert EUTF health benefits to a self-insured model with an ASO contract. This would not affect negotiated benefits or EUTF management, and the state would bear full direct responsibility for assuring continued funding of health benefits. Pre-funding is less important with the self-insured model, since benefits are guaranteed directly by the state, and do not depend on payments to an insurance middle-man. Self-insurance could save the state around $175 million annually in administrative costs, and another $500 million from eliminating pre-funding. For Medicaid, Hawaii should heed the experience of Connecticut, which terminated its Medicaid managed care program in 2012 in favor of a self- insured managed fee-for-service system called Primary Care Case Management (PCCM). In the four years prior, Connecticut Medicaid costs rose 45%. After the conversion, Medicaid costs stabilized immediately. Six years later physician participation had improved substantially, ER visits were down 25%, hospitalizations were down about 6%, and per-capita Medicaid costs had dropped 14% compared to 2012. Administrative costs dropped from 20-25% under at-risk managed care to 2.8% with PCCM, including the cost of the ASO contract. Hawaii’s Medicaid program just issued a request for proposal (RFP) to renew contracts with managed care insurance plans effective July 1, 2021, locking in the administrative waste and access problems of our privatized managed care system for another six years. We urge the Ige administration to rescind the managed care RFP, and use the Connecticut template to rapidly design a PCCM system with a non-risk ASO contract. Savings comparable to Connecticut would mean around $175 million per year for the state budget. Hawaii law designates the Hawaii Health Authority with responsibility for overall health planning, but it has been sidelined for the past nine years. It should be re-activated and empowered to assist the state in designing cost- effective self-insured systems with ASO contracts for both EUTF health benefits and Medicaid. Savings could be in the range of $850 million per year.

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment