The Single-Payer Party? Democrats Shift Left on Health Care

by Alexander Burns and Jennifer Medina - NYT - June 3, 2017

For years, Republicans savaged Democrats for supporting the Affordable Care Act, branding the law — with some rhetorical license — as a government takeover of health care.

Now, cast out of power in Washington and most state capitals, Democrats and activist leaders seeking political redemption have embraced an unlikely-seeming cause: an actual government takeover of health care.

At rallies and in town hall meetings, and in a collection of blue-state legislatures, liberal Democrats have pressed lawmakers, with growing impatience, to support the creation of a single-payer system, in which the state or federal government would supplant private health insurance with a program of public coverage. And in California on Thursday, the Democrat-controlled State Senate approved a preliminary plan for enacting single-payer system, the first serious attempt to do so there since then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, vetoed legislation in 2006 and 2008.

With Republicans in full control of the federal government, there is no prospect that Democrats can put in place a policy of government-guaranteed medicine on the national level in the near future. And fiscal and logistical obstacles may be insurmountable even in solidly liberal states like California and New York.

Yet as Democrats regroup from their 2016 defeat, leaders say the party has plainly shifted well to the left on the issue, setting the stage for a larger battle over the health care system in next year’s congressional elections and the 2020 presidential race. Their liberal base, emboldened by Senator Bernie Sanders’s forceful advocacy of government-backed health care last year, is increasingly unsatisfied with the Affordable Care Act and is demanding more drastic changes to the private health insurance system.

In a sign of shifting sympathies, most House Democrats have now endorsed a single-payer proposal. Party strategists say they expect that the 2020 presidential nominee will embrace a broader version of public health coverage than any Democratic standard-bearer has in decades.

RoseAnn DeMoro, the executive director of National Nurses United and the California Nurses Association, powerful labor groups that back single-payer care, said the issue had reached a “boiling point” on the left.

Supporters of universal health care, including activists with Ms. DeMoro’s union, repeatedly interrupted speakers at the California Democratic Party’s convention in May, challenging party leaders to embrace socialized medicine. Demonstrators waving signs with single-payer slogans have become a regular feature at town hall meetings hosted by members of Congress.

“There is a cultural shift,” said Ms. DeMoro, who was a prominent backer of Mr. Sanders. “Health care is now seen as something everyone deserves. It’s like a national light went off.”

Representative Rick Nolan of Minnesota, a populist Democrat whose district voted for President Trump by a wide margin, said he had rarely seen core Democratic voters as enthusiastic about an issue as they were about single-payer health care. Mr. Nolan said he would support creating a state-level system in Minnesota, but believed the party’s goal should be a national law.

He warned Democrats against being too cautious on health care or trusting that they could passively reap the benefits of Republican missteps, saying that his party needed a more boldly “aspirational” health care platform.

Rank-and-file Democrats, Mr. Nolan said, “are energized in a way I have not witnessed in a long, long time.”

At this point, state and federal single-payer proposals appear mainly to embody the sweeping ambitions of a frustrated party, rather than to map a clear way forward on policy. A handful of legislators in Democratic states — some positioning themselves to run for higher office — have proposed single-payer bills, including in New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Only in California does the legislation appear to have at least a modest chance of being approved this year.

Even there, State Senator Ricardo Lara, an author of the bill, said his legislation would not clear the State Assembly without detailing how expanded coverage would be financed. The proposal currently lacks a complete funding plan.

The bill would mandate far more comprehensive access to health care, with no out-of-pocket costs, for all California residents at an estimated cost of $400 billion annually. Roughly half would come from existing public money spent on health care, but the rest would require new taxes. Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat who once campaigned for president supporting single-payer care, has questioned how the state can plausibly foot the bill.

Should California enact a single-payer law, it would still require a waiver from Washington to redirect federal funding to the state program — which might be difficult with Trump appointees running the Department of Health and Human Services.

But Mr. Lara said that Mr. Trump’s election, and subsequent Republican efforts to unwind the Affordable Care Act, had upended the conversation about health care among Democrats. He said he would have been unlikely to press for single-payer under a Democratic president.

“I no longer have the luxury of going step by step,” Mr. Lara said. “We need to do a single-payer or we’re going to be in a position where millions of people are going to lose coverage.”

There remains considerable skepticism among senior Democrats about a single-payer plan, and party strategists fear that proposing a potentially divisive health care agenda would offer Republicans a welcome diversion from their own tortured wrangling over the Affordable Care Act.

At a briefing with reporters last month, the House minority leader, Representative Nancy Pelosi of California, replied with a flat “no” when asked if Democrats should make single-payer a central theme in 2018. She said state-level action was more appropriate, though she said she supported the idea in concept.

“The comfort level with the broader base of the American people is not there yet,” Ms. Pelosi said.

In the past, top Democrats — including President Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton— have suggested more incremental approaches, proposing the creation of an optional government health plan that people could buy into or lowering the eligibility age for Medicare.

Democrats were unable to pass either of those measures into law the last time they controlled Congress and the White House, in 2010, because they failed to draw unanimous support from both liberal and centrist Democrats. Mr. Obama never tried to create a full single-payer system, and Mrs. Clinton described the idea as unachievable during the 2016 campaign.

A study published in January by the Pew Research Center found that about 40 percent of Democrats favored a single-payer system, including a slight majority of self-described liberal Democrats. Among all Americans, support was markedly lower: Just 28 percent said government should be the sole provider of care.

But a sizable majority — about three in five Americans — said the government had a responsibility to ensure everyone had health care. And the idea of single-payer health care has stirred interest among some business leaders, like Warren E. Buffett and Charles Munger, who see health care costs as a drag on the economy.

Karen Politz, a senior fellow at the Kaiser Family Foundation who has tracked the single-payer debate for years, said it would be difficult to persuade the country to move to an all-government health care system — a disruptive process that would likely lead to higher taxes in place of the premiums people now pay to insurance companies.

Even if most consumers paid less over all, as single-payer proponents claim, Ms. Politz said, morphing premiums into taxes would be culturally and politically challenging. “It does involve big government, and it’s kind of baked into the American psyche that we resist that,” she said.

Still, Democrats acknowledge that there is a palpable appetite on the left for comprehensive government health care. A number of the party’s potential 2020 presidential contenders, including Senators Cory Booker of New Jersey and Kamala Harris of California, have signaled support for some version of universal government care, though neither Mr. Booker nor Ms. Harris has endorsed the single-payer proposal in his or her home state.

In the House, 112 of the 193 Democrats have co-sponsored a single-payer billproposed by Representative John Conyers Jr. of Michigan and called the “Expanded and Improved Medicare for All Act.” Until recently, the bill had attracted a fraction of that support.

The Conyers proposal would effectively void the current private health insurance system and impose new taxes on wealthy people and on certain kinds of income to pay for benefits. In May, the bill won a symbolically telling endorsement from Representative Joseph Crowley of New York, the chairman of the Democratic caucus and a leading possible successor for Ms. Pelosi.

Mr. Crowley said his support for the bill was “part practical, part aspirational,” conceding that there was no immediate path to making it law.

“You can’t do this with 110 votes,” he said.

The Doctor Is In. Co-Pay? $40,000.

by Nelson D. Schwartz - NYT - June 3, 2017

SAN FRANCISCO — When John Battelle’s teenage son broke his leg at a suburban soccer game, naturally the first call his parents made was to 911. The second was to Dr. Jordan Shlain, the concierge doctor here who treats Mr. Battelle and his family.

“They’re taking him to a local hospital,” Mr. Battelle’s wife, Michelle, told Dr. Shlain as the boy rode in an ambulance to a nearby emergency room in Marin County. “No, they’re not,” Dr. Shlain instructed them. “You don’t want that leg set by an E.R. doc at a local medical center. You want it set by the head of orthopedics at a hospital in the city.”

Within minutes, the ambulance was on the Golden Gate Bridge, bound for California Pacific Medical Center, one of San Francisco’s top hospitals. Dr. Shlain was there to meet them when they arrived, and the boy was seen almost immediately by an orthopedist with decades of experience.

For Mr. Battelle, a veteran media entrepreneur, the experience convinced him that the annual fee he pays to have Dr. Shlain on call is worth it, despite his guilt over what he admits is very special treatment.

“I feel badly that I have the means to jump the line,” he said. “But when you have kids, you jump the line. You just do. If you have the money, would you not spend it for that?”

Increasingly, it is a question being asked in hospitals and doctor’s offices, especially in wealthier enclaves in places like Los Angeles, Seattle, San Francisco and New York. And just as a virtual velvet rope has risen between the wealthiest Americans and everyone else on airplanes, cruise ships and amusement parks, widening inequality is also transforming how health care is delivered.

Money has always made a big difference in the medical world: fancier rooms at hospitals, better food and access to the latest treatments and technology. Concierge practices, where patients pay several thousand dollars a year so they can quickly reach their primary care doctor, with guaranteed same-day appointments, have been around for decades.

But these aren’t the concierge doctors you’ve heard about — and that’s intentional.

Dr. Shlain’s Private Medical group does not advertise and has virtually no presence on the web, and new patients come strictly by word of mouth. But with annual fees that range from $40,000 to $80,000 (more than 10 times what conventional concierge practices charge), the suite of services goes far beyond 24-hour access or a Nespresso machine in the waiting room.

Indeed, as many Americans struggle to pay for health care — or even, with the future of the Affordable Care Act in question on Capitol Hill, face a loss of coverage — this corner of what some doctors call the medical-industrial complex is booming: boutique doctors and high-end hospital wards.

“It’s more like a family office for medicine,” Dr. Shlain said, referring to how very wealthy families can hire a team of financial professionals to manage their fortunes and assure the transmission of wealth from generation to generation.

Only in this case, they are managing health, on behalf of clients more than equipped to pay out of pocket — those for whom, as Dr. Shlain put it, “this is cheaper than the annual gardener’s bill at your mansion.”

There are rewards for the physicians themselves, of course. A successful internist in New York or San Francisco might earn $200,000 to $300,000 per year, according to Dr. Shlain, but Private Medical pays $500,000 to $700,000 annually for the right practitioner.

For patients, a limit of no more than 50 families per doctor eliminates the rushed questions and assembly-line pace of even the best primary care practices. House calls are an option for busy patients, and doctors will meet clients at their workplace or the airport if they are pressed for time.

In the event of an uncommon diagnosis, Private Medical will locate the top specialists nationally, secure appointments with them immediately and accompany the patient on the visit, even if it is on the opposite coast.

Meanwhile, for virtually everyone else, the typical wait to see a doctor is getting longer.

Waiting Longer to See a Doctor

The average number of days to get a non-emergency doctor’s appointment in 2009 versus this year among five specialties: cardiology, dermatology, orthopedic surgery, obstetrics/ gynecology or family medicine.

A survey released in March by Merritt Hawkins, a Dallas medical consulting and recruiting firm, found it takes 29 days on average to secure an appointment with a family care physician, up from 19.5 days in 2014. For some specialties, the delays are similarly long, with a 32-day wait to see a dermatologist, and a 21-day delay at the typical cardiologist’s office.

And some patients are willing to pay a lot to avoid that. MD Squared, an elite practice that charges up to $25,000 a year, opened a Silicon Valley office in 2013 and within months had a waiting list to join.

“You have no idea how much money there is here,” said Dr. Harlan Matles, who specializes in internal medicine and joined MD Squared after working at Stanford, where he treated 20 to 25 patients a day and barely had time to talk to them. “Doctors are poor here by comparison.”

Doctors as Asset Managers

Nowhere is the velvet rope in health care rising faster than here in Northern California, where newfound tech wealth, abundant medical talent and a plethora of health-conscious patients have created a medical system that has more in common with a luxury hotel than with the local clinic.

In fact, before founding Private Medical, Dr. Shlain, 50, worked as the on-call doctor at the Mandarin Oriental hotel here, an experience he said taught him about how to provide five-star service as well as good medical care.

Private Medical started 15 years ago with a single location in San Francisco, and has since opened practices in nearby Menlo Park, in 2011, and Los Angeles, in 2015. Dr. Shlain is now eyeing an expansion into New York, Seattle and Santa Monica, Calif.

The annual fee covers the cost of visits, all tests and procedures in the office, house calls and just about anything else other than hospitalization, as well as personalized annual health plans and detailed quarterly goals for each patient.

Although Private Medical provides its patients with doctors’ cellphone numbers and same-day appointments, like more conventional concierge practices do, Dr. Shlain does not like the term “concierge care.”

“When I’m at a country club or a party and people ask me what I do, I say I’m an asset manager,” Dr. Shlain explained. “When they ask what asset, I point to their body.”

“We organize health care for the entire family,” he said, sitting in his hip-but-not-too-fancy office in a nondescript building in upscale Presidio Heights. Dr. Shlain and his team will coordinate treatment for grandparents in a nursing home and care for their middle-aged children, as well as provide adolescent or pediatric medicine for the grandchildren.

For example, when a teenage patient with a history of depression or anxiety moves across the country to Boston for college, Private Medical will line up a top psychiatrist near the school beforehand so a local professional is on call in case there is a recurrence. Or if a middle-aged patient is found to have cancer, Dr. Shlain can secure an appointment in days, not weeks or months, with a specialist at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston or Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“It’s not because we pay them,” he added. “It’s because we have relationships with doctors all over the country.”

‘We Can Get You In’

As with the ever more rarefied tiers of frequent-flier programs or V.I.P. floors at hotels, the appeal of MD Squared and Private Medical is about intangibles like time, access and personal attention.

“I am able to give the time and energy each patient deserves,” said Dr. Matles, the MD Squared physician in Menlo Park. “I wish I could have offered this to everyone in my old practice, but it just wasn’t feasible.”

So in addition to providing immediate access to specialists, concierge doctors also come in handy when otherwise wealthy, powerful people find themselves flummoxed by a health care system that is opaque to outsiders.

“If you need to go to Mass General, we can get you in,” Dr. Matles said. “We are connected. I don’t know if I can get you to the front of the line, but I can make it smoother. Doctors like to help other doctors.”

But for all their confidence about the advantages of their particular brand of concierge medicine, these physicians are quick to admit they struggle with the ethical issues of providing elite treatment for a wealthy few, even as tens of millions of American struggle to afford basic care.

Dr. Shlain founded a software start-up, HealthLoop, that aims to “democratize” his boutique approach by allowing patients to communicate directly with their doctors through daily digital checklists and texts.

He sees no reason that the medical world should not respond to consumer demand like any other player in the service economy. “Whenever I bump into a bleeding-heart liberal, which I am, I mention that schools, housing and food are all tiered systems,” he said. “But health care is an island of socialism in a system of tiered capitalism? Tell me how that works.”

Dr. Howard Maron, who founded MD Squared, is similarly candid about the new reality of ultra-elite medical care.

“In my old waiting room in Seattle, the C.E.O. of a company might be sitting next to a custodian from that company,” he recalled. “While I admired that egalitarian aspect of medicine, it started to appear somewhat odd. Why would people who have all their other affairs in order — legal, financial, even groundskeepers — settle for a 15-minute slot?”

It’s a fair question — but the new approach does not sit so well with veteran practitioners like Dr. Henry Jones III, one of Silicon Valley’s original concierge doctors at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation’s Encina Practice. He charges $370 a month, a fraction of what newer entrants in the area like MD Squared and Private Medical do. “It’s priced so the average person in this ZIP code can afford it,” he said.

A third-generation doctor from Boston, Dr. Jones offers a version of concierge medicine that is a way of providing more personalized service — the way doctors did when he graduated from medical school more than four decades ago — rather than delivering a different standard of care.

“Encina is like a Unesco World Heritage site — we practice medicine the way it has been traditionally practiced,” he said. “Just because you’re an Encina patient doesn’t mean you can go to the front of the line, unless you need to because of your case.”

Plusher Quarters

Not far from Dr. Jones’s office in Palo Alto, the new wing of Stanford’s hospital is taking shape. Designed by the star architect Rafael Viñoly, it will feature a rooftop garden and a glass-paneled atrium topped with a 65-foot dome. And unlike the old wing, all of the new building’s 368 rooms will be single occupancy, a crucial amenity for hospitals competing to attract elite patients from across the United States and overseas.

Stanford raised a significant portion of the project’s $2 billion cost by cultivating wealthy patients — a funding model used by university hospitals around the country, which is especially effective among the millionaires and billionaires of Silicon Valley.Not to be outdone, Lenox Hill Hospital in New York recently hired a veteran of Louis Vuitton and Nordstrom, Joe Leggio, to create an atmosphere that would remind V.I.P. patients of visiting a luxury boutique or hotel, not a hospital. “This is something that patients asked for, and we want to go from three-star service to five-star service,” said Mr. Leggio, the hospital’s director of patient and customer experience.

In its maternity ward, the Park Avenue Suite costs $2,400 per night, twice what a deluxe suite at the Carlyle Hotel down the street commands, but that’s not a problem for well-heeled new parents. Beyoncé and Jay Z welcomed their baby, Blue Ivy, into the world at Lenox Hill, as did Chelsea Clinton and her husband, and Simon Cowell and his girlfriend.

With a separate sitting room for family members, a kitchenette and a full wardrobe closet, the suite overlooking Park Avenue is a world away from the semiprivate experience upstairs at the hospital, where families share an old-fashioned room divided by a curtain. Slightly less exalted but still private rooms in Lenox Hill’s maternity ward range from $630 to $1,700 per night.

As the stream of celebrity couples suggests, there is plenty of demand for these upscale options, crowding out traditional maternity wards. Lenox Hill is replacing some of its shared maternity rooms with private rooms, a far more profitable offering for hospitals since patients pay for them out of pocket, not through insurance plans that can bargain down rates.

Hospital executives argue that giving the well heeled extra attention is a way of keeping the lights on and providing care for ordinary middle- and even upper-middle-class patients, as reimbursements from private insurers and the federal government shrink. “I need to succeed to pay for the children we are bringing in from all over the world and treat for free,” said Dr. Angelo Acquista, a veteran pulmonologist who leads Lenox Hill’s executive health and international outreach programs.

Then there are the red blankets that some big Stanford benefactors receive when they check in as patients. For doctors and nurses, it is a quiet sign of these donors’ special status, which is also noted in their medical records.

“You don’t get better care,” Dr. Jones said. “But maybe the dean comes by, and if it’s done well, it’s done invisibly. It’s an acknowledgment of a contribution to the organization.”

Valuing Relationships

Rex Chiu, an internist with Private Medical in Menlo Park, spent more than a decade as a doctor on Stanford’s faculty. “I loved my time at Stanford, but I was spending less and less time with patients,” he said. “Fifteen or 20 minutes a year with each patient isn’t enough.”

“We all say we should get the same care, but I got sick and tired of waiting for that to happen,” he added. “I decided to go for quality, not quantity.”

Besides more money, the calmer pace of high-end concierge medicine is also a major selling point for physicians — Dr. Matles said he never made it to an event at his children’s school until he joined MD Squared. But for Dr. Sarah Greene, it wasn’t really the money or the lifestyle that led her to Private Medical.

“I really have time to think about my patients when they’re not in front of me,” said Dr. Greene, a pediatrician who joined the company’s Los Angeles practice in October. “I may spend a morning researching and emailing specialists for one patient. Before, I had to see 10 patients in a morning, and could never spend that kind of time on one case.”

Getting in the door as a new hire isn’t easy. When it comes to credentials like college, medical school and residency, Dr. Shlain said, “at least two out of the three need to be Ivy League, or Ivy League-esque.”

In many ways, today’s elite concierge physician provides the same service as the family doctor did a half-century ago for millions of Americans, except that it is reserved for the tiny sliver of the population who can pay tens of thousands of dollars annually for it.

“I didn’t know this level of care was possible,” said Trevor Traina, a serial entrepreneur here who is a patient of Dr. Shlain’s. “I have a better relationship with my veterinarian than the doctors I went to in the past.”

What about everyone else? Mr. Traina doesn’t see much future for the conventional family doctor, except for patients who go the concierge route.

“The traditional model of having a good internist is dying,” said Mr. Traina, a scion of a prominent family here that arrived with the California Gold Rush. “Even the 25-year-olds at my company either have some form of concierge doc, or they’ll just go to an H.M.O. or a walk-in clinic. No one here has a regular doctor anymore.”

From Maine, a Call for a More Measured Take on Health Care

by Jennifer Steinhauer - NYT - June 5, 2017

BANGOR, Me. — Hundreds of miles from the health care debate that will begin again this week in Congress, lobstermen here are out in force, bees are furiously pollinating the state’s famous blueberries and part-time workers are preparing for another summer tourist season.

As a result of their short-term spike in income, many of Maine’s working class will likely lose some or all of their health insurance subsidy, a feature of the federal health care law, which has been a complicated blessing for the citizens of Maine.

Senator Susan Collins, Republican of Maine, has spent a lot of time thinking about how to deal with these “subsidy cliffs,” even as her party’s leaders press for the wholesale repeal of the Affordable Care Act, President Barack Obama’s signature domestic achievement.

As she and a handful of other Republican senators think about repairs rather than replacements, discussions that will intensify this week after the Memorial Day break, they are frustrating the grander ambitions of the Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell of Kentucky — not to mention President Trump — to unravel the law as the House did last month.

Ms. Collins’s résumé (she once oversaw Maine’s insurance bureau), her relentless practicality and her state’s particular vulnerability within the health care debate — its population is old and largely poor, with a sizable part-time work force — have placed her at the center of an issue that conservatives have tried to dominate in Congress.

“There is no denying that the Affordable Care Act has made insurance available to millions of Americans and allowed people to leave corporate jobs and start businesses,” Ms. Collins said. “We are disproportionately affected, which is one reason I’ve spent so much energy on this issue.”

Ms. Collins, omitted from the working group convened by Mr. McConnell, has formed a bipartisan working group that may help build a foundation for future changes should Senate Republicans fail on their own, which seems increasingly likely.

It is reminiscent of when Democrats tried desperately to woo Senator Olympia Snowe, who also represented Maine, to their side in the last health care debate. They won her vote for the health bill in the Finance Committee, only to lose it on the Senate floor.

“Obamacare created a mind-set here that the federal government can be a partner in providing health insurance,” said Lee Umphrey, the chief executive of the Harrington Family Health Center, where 1,500 residents in a rural county east of Bangor have enrolled in health insurance plans since the law was enacted.

“Senator Collins has had an open mind, but it’s hard for her with the more conservative pockets here in Maine and her caucus back in Washington,” Mr. Umphrey said.

The House bill would roll back state-by-state expansion of Medicaid, and replace income-based government subsidies to buy insurance policies on the act’s marketplaces with tax credits of $2,000 to $4,000 a year, depending on a person’s age. It would also offer states the ability to let insurers charge higher premiums for some people with pre-existing medical conditions.

While Maine did not expand its Medicaid program — something providers here greatly lament — the new subsidies increased the number of individual policyholders to 80,000 from 30,000 since the law was enacted.

Should a bill like the House measure pass, Americans between 50 and 64 will be the most vulnerable to steep rate increases. The impact would be particularly acute in Maine, where the median age is 43, the oldest in the nation.

Like many states with high health care costs, Maine is largely rural — and nearly 22 percent of the state’s workers have part time jobs, well above the national average of 17 percent.

But the health care law has allowed self-employed residents and owners of very small businesses to have insurance for the first time in years. “It’s been good to have it,” said Charles Smith, a lobsterman from Jonesport whose wife and three teenagers were sporadically without insurance for years before the law.

Ms. Collins has been a critic of the Affordable Care Act since it was enacted. She has cited the instability in the insurance markets; the increasing costs of premiums, especially in rural northern areas; and the scarcity of health care facilities that accept the plans.

During the Trump presidency, she said, the tension over access “has been exacerbated by the administration’s mixed messages on cost sharing.” The administration has wavered on whether to continue government payments to health insurance companies to offset their customers’ out-of-pocket medical expenses.

“The uncertainty is extremely problematic,” said Eric A. Cioppa, the superintendent of the Maine Bureau of Insurance, who said carriers could not fix their rates without knowing the fate of those subsidies. “If they don’t get a subsidy, I fully expect double-digit increases for three carriers on the exchanges here.”

Ms. Collins also said she would like to see a fix to the “wage cliff,” in which a single dollar increase over the Affordable Care Act’s income threshold can cost a worker the full value of his insurance subsidy. It is a special problem for seasonal workers whose incomes fluctuate throughout the year.

“I really dislike that the law discourages work and pay raises,” she said.

Maine has been viewed by Republicans as a possible model for some reforms. It was one of a handful of states that embraced a “guaranteed issue” policy of health insurance, regardless of pre-existing medical conditions, and it created “invisible” high-risk pools to help sick people buy insurance and stabilize the markets.

Republicans cite Maine as the model for the risk pool in the House measure, but Ms. Collins notes that the House bill does not fund state-based risk pools anywhere near the level that Maine has.

“One of the problems with the exchanges is that the pools are not large enough,” she said. “It would cost $15 billion annually to expand nationally a patient stability fund like Maine did.”

A state bill that loosened community rating rules and deregulated the insurance market could also be a model for a Republican health care bill that allows states more waivers from federal rules. Many state health care experts see that as a way to get more flexibility and experimentation in insurance markets.

For instance, Ms. Collins thinks Maine should embrace a Medicaid expansion modeled on the one adopted by Indiana after the state obtained a waiver from the Obama administration. Indiana included managed-care plans in its Medicaid expansion and a requirement that poor people contribute to savings accounts, which are then applied to the portion of their medical bills.

Maine also has one of the few viable health insurance cooperatives in the nation, which was hugely popular but has struggled to stay solvent because of high health care costs for Maine’s newly insured. It is on a better footing this year.

Maine health care experts are watching Ms. Collins carefully in the debate, which Republicans would like to see reach its climax before the July Fourth recess.

“I think she is very conscious of the fact that if you move forward with a plan that gives tax credits to higher-income people but not a 60-year-old in Presque Isle, that is not a good move for our state,” said Emily Brostek, the executive director of Consumers for Affordable Health Care in Augusta, Me.

Rural Maine voters, who largely supported Mr. Trump in his election, are watching, too.

“I like what I’ve got,” said Mr. Smith, the lobsterman, who is an independent and voted for Mr. Trump. “If they get rid of Obamacare, I would say I would blame the Republicans.”

Harvard Pilgrim seeks 40% rate increase for Affordable Care Act plans in Maine

by J. Craig Anderson - Portland Press Herald - June 3, 2017

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care is requesting an average premium increase of nearly 40 percent for its individual plans on Maine’s Affordable Care Act marketplace in 2018.

The requested annual increase of 39.7 percent is by far the largest ever sought by any of Maine’s three remaining ACA marketplace insurance providers. A year ago, the largest increase was 25.5 percent, a hike requested – and received – by Community Health Options.

In the past, federal subsidies based on income have largely offset increases in out-of-pocket costs for low- to moderate-income policyholders, but Republican efforts to replace the ACA have created uncertainty about the future of those subsidies.

Harvard Pilgrim cited higher costs and market instability as reasons for the magnitude of its requested increase, and suggested that it might have to exit the marketplace altogether unless Congress acts.

“While we remain committed to the principle of everyone having access to affordable coverage, we can only continue to participate in the exchanges if there is stability in this market, and that will only come with immediate action from Washington,” company spokeswoman Joan Fallon said in a written statement.

The state Bureau of Insurance set a deadline of 4 p.m. Friday for Maine’s three ACA marketplace insurers to submit their rate increase requests for 2018. While the bureau said it did not plan to publish the documents until next week, Harvard Pilgrim and Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield agreed to share the amount of their requests with the Portland Press Herald on Friday.

Anthem said it is requesting an average premium increase of 21.2 percent in Maine for individual ACA plans, citing higher costs and heavier usage by members. It also expressed concerns about market instability and said its rates and services could be subject to further changes.

Both Harvard Pilgrim and Anthem said their rate increase requests assume that the cost-sharing reduction subsidies will continue to be funded in 2018.

However, the House Republicans’ ACA replacement bill, known as the American Health Care Act, would eliminate income-based subsidies in favor of tax credits based on age. Health experts have said the change would significantly reduce affordability for older policyholders.

86,000 MAINERS HAVE ACA PLANS

“Without certainty of funding before final decisions need to be made for 2018, Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield will need to evaluate appropriate adjustments to our filings such as reducing service area participation, requesting additional rate increases, eliminating certain product offerings or exiting the individual ACA-compliant market in Maine altogether,” Anthem spokesman Colin Manning said in a written statement.

Community Health Options, Maine’s largest ACA insurance provider, did not respond to requests Friday for its proposed rate increase for 2018.

Together, Harvard Pilgrim and Anthem insure about 32 percent of the 86,000 Mainers with ACA-compliant health insurance. In Maine, Harvard Pilgrim has about 10,500 ACA members, Anthem has about 16,750 and CHO has 58,750. Aetna had been an ACA insurer in Maine but dropped out as of 2017.

Sen. Angus King, an independent, sent letters to Maine’s three ACA insurers on May 26 asking if uncertainty about the law’s future will end up raising the cost of insurance. King asked the insurers to submit a hypothetical rate comparison that accounts for price increases resulting directly from partisan efforts to undermine the ACA.

“These rate increases appear to confirm Sen. King’s concerns that decisions by the administration and Congress are undermining the Affordable Care Act, creating significant instability in the individual health care market, and affecting premiums,” King spokesman Scott Ogden said in a written statement. “Sen. King is interested in knowing what percentage of these increases are the result of these misguided efforts, which is why he has sent a letter to Maine’s insurers asking them to provide rate comparisons and he looks forward to receiving that information. In the meantime, he continues to urge his colleagues to abandon efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, and, instead, come together to make meaningful improvements to the law – and do so immediately.”

Representatives of Harvard Pilgrim, Anthem and CHO all said this week that they had received King’s inquiry and planned to respond.

A spokeswoman for Sen. Susan Collins, a Republican, said another ACA replacement Bill that Collins introduced in January with Sen. Bill Cassidy. R-Louisiana, would do a better job of stabilizing the market than either the current law or the House’s AHCA. The bill would allow states to maintain what they have or choose other options to provide health insurance to their residents.

“As evidenced by these requests for massive, double-digit rate increases, the individual market is under considerable stress and in danger of collapsing if Congress does not act,” Collins spokeswoman Annie Clark said in a written statement. “The unsustainable trajectory of skyrocketing premiums under current law has reduced the affordability and accessibility of health care for thousands of Mainers across our state.”

PREMIUMS UP SHARPLY SINCE 2013

According to a study released in May by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, average monthly premiums for individual plans on the ACA marketplace in Maine have increased by 55 percent since 2013, the ACA’s first year of implementation. During that time, the average monthly premium has increased from $335 to $518, it said.

Average out-of-pocket costs for ACA insurance premiums are much lower and have increased by far less because of the subsidies. According to a report issued in April by the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit organization focusing on national health issues, out-of-pocket costs for ACA insurance have remained between 5 percent and 10 percent of annual income in Maine and across the United States.

The rate increases requested by Maine’s three ACA-compliant insurance providers are preliminary and are subject to approval by the Bureau of Insurance.

The bureau, which regulates rate requests by insurance companies, approved 2017 rate increases of 25.5 percent for CHO, 21.1 percent for Harvard Pilgrim and 18 percent for Anthem. Most of policyholders’ out-of-pocket costs associated with those increases are being offset by government subsidies.

About 90 percent of Mainers who have individual plans under the ACA qualify for subsidies because they earn between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty limit. In Maine, the 400 percent threshold is $97,000 for a family of four.

The California Senate Just Passed Single-Payer Health Care

by John Nichols - The Nation - June 2, 2017

If health care is a right—and it is—the only honest response to the current crisis is the single-payer “Medicare For All” reform that would bring the United States in line with humane and responsible countries worldwide.

It is unfortunate that Donald Trump, who once seemed to recognize the logic of single payer, has aligned himself with House Speaker Paul Ryan’s scheme to make health a privilege rather than a right—and to use a “reform” of the Affordable Care Act as a vehicle to reward wealthy campaign donors with tax cuts and sweetheart deals. The debate in Washington is so cruel and unusual that it is easy to imagine that the cause of single payer must be doomed in America.

Not so. The movement for single payer is for real, and it’s winning in California.

The state Senate voted 23 to 14 on Thursday in favor of SB 562, a single-payer proposal that would guarantee universal health care to all Californians. “What we did today was really approve the concept of a single-payer system in California,” declared state Senator Ricardo Lara, a key advocate for the bill, following the vote.

“California Senators have sent an unmistakable message today to every Californian and people across the nation,” declared RoseAnn DeMoro, the executive director of the California Nurses Association and National Nurses United, which led the fight for the “Healthy California Act.”

“We can act to end the nightmare of families who live in fear of getting sick and unable to get the care they need due to the enormous cost,” DeMoro continued. “We’ve shown that healthcare is not only a humanitarian imperative for the nation, it is politically feasible, and it is even the fiscally responsible step to take.”

That’s true. According to a review of a new NNU-sponsored study by the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts Amherst: “SB 562 would produce substantial savings for households in healthcare costs as a share of their income, and California businesses, which would also see reduced payroll costs for health care expenditures.”

The California proposal still must be approved by the California state Assembly and, eventually, by Governor Jerry Brown. Budget plans must be developed. The fight is far from over. But a hurdle has been cleared and DeMoro is right to say that: “This is a banner day for California, and a moral model for the nation.”

What would California's proposed single-payer healthcare system mean for me?

by Melanie Mason - LA Times - June 1, 2017

Q&A

The prospect of a universal single-payer healthcare system in California — in which the state covers all residents’ healthcare costs — has enthralled liberal activists, exasperated business interests and upended the political landscape in the state Capitol. But some are still trying to sort out what exactly all the fuss is about.

Let’s start with some caveats. This proposal faces a steep climb before it becomes a reality. It almost certainly will require new taxes to finance it and that would entail the major lift of cobbling together a supermajority of votes in both houses of the Legislature for approval. Even if that happens, it still faces another hurdle: Gov. Jerry Brown, who has been publicly chilly toward the idea. Voters would also need to OK the proposal to exempt it from spending limits and budget formulas in the state constitution. And there’s yet another big obstacle: getting approval from the federal government to repurpose Medicare and Medicaid dollars.

Still, single-payer has emerged as a litmus test for California Democrats. The proposal, by state Sens. Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens) and Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) is still evolving, but here’s what we know so far about the bill and how it would work:

What is single payer? Is it the same thing as a “public option?”

- Under a single-payer plan, the government replaces private insurance companies, paying doctors and hospitals for healthcare.

- That’s different than a public option, in which the government offers an alternative to other insurance plans on the market.

It’s all in the name: In a single-payer system, one entity — in this case, the state of California — covers all the costs for its residents’ healthcare. Effectively, the government would step into the role that insurance companies play now, paying for all medically necessary care.

A number of countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom, have single-payer models. While there have been calls for a similar system in the United States for decades, the cause was energized by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, which backed a “Medicare for all” healthcare system, modeled on the existing program for Americans aged 65 and older.

Other efforts to enact state-level single-payer systems have fallen flat. A 2011 program in Vermont was abandoned three years later due to financing concerns. Last year, voters in Colorado rejected a ballot initiative to create such a program.

The California bill bears the imprints of Sanders’ campaign — and of the California Nurses Assn., which has long pressed for a single-payer plan. It has become a rallying cry for the progressive flank of the Democratic party.

“The model here is not the United Kingdom or Canada,” said Darius Lakdawalla, a health economist at University of Southern California. “The model here is Medicare.”

The proposal is different than a “public option,” in which the government subsidizes an insurance plan that competes with private insurers. A public option was debated in the run-up to passage of the Affordable Care Act, but ultimately not included. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi recently returned to the concept, telling California Democrats at their convention in May, “I believe California can lead the way for America by creating a strong public option.”

Gerald Kominski, a professor of health policy at UCLA, said a public option would offer a backstop in states where insurers have dropped out of the Obamacare marketplace. Covered California, the state’s marketplace, is generally seen as robust compared to other states.

“Sure, there’s room for a public option in California,” Kominski said, “but I’m not convinced there’s an overwhelming need.”

How would this change how I get healthcare?

- No more coverage through work or through federal public programs — it would all be in one state-subsidized plan.

- Virtually all healthcare costs would be covered.

Whether you’re insured through an employer, through Covered California or on public programs such as Medi-Cal, as long as you’ve established California residency — regardless of legal immigration status — you would be enrolled in a single plan, which the bill’s backers call the “Healthy California” plan. That would eliminate the need for employer-provided plans and other commercial options.

Michael Lighty, policy director for the California Nurses Assn., put it bluntly: “You’ll never have to deal with an insurance company again.”

Benefits would be generous, including all inpatient and outpatient care, dental and vision care, mental health and substance abuse treatment, and prescription drugs. Patients would be able to see any healthcare provider of their choosing.

I’m on Medicare. What would this mean for me?

- Federal programs like Medicare and Medi-Cal would be merged into the single-payer plan.

- But there’s no guarantee the Trump administration would approve such a change.

Older Californians on Medicare would also be wrapped into this plan. The plan envisions using all the existing federal dollars going toward Medicare and Medi-Cal beneficiaries in California in the state’s single-payer model.

But there’s a hitch: The federal government — a frequent punching bag for California Democrats at the moment — would need to grant a waiver to redirect that money.

“The question is: Will the Trump administration approve such a waiver?” Kominski said.

In one sense, he said, the request could align with conservative ideology that calls for increased power of states relative to the federal government.

“On the other hand, for political purposes, I can see the Trump administration saying there’s no way we can sign a waiver,” Kominski added.

Supporters say they believe they can obtain a waiver, but have gotten no indication from the Trump administration that they’d be inclined to sign it. It is unclear what would happen if they cannot get federal approval.

This is a sea change in the way healthcare would be organized in California.— Darius Lakdawalla, professor of economics, University of Southern California

Would this affect how much I spend on healthcare?

- No more co-pays, premiums or deductibles

- But Californians would be hit with higher taxes

At this point, it’s hard to say. The existing language of the proposal does away with a lot of the financial burdens associated with the current healthcare system, such as premiums, deductibles and co-pays.

“When [patients] go to a provider, they won’t have to pay anything,” Lighty said. “They won’t get a bill from the insurance company after surgery. They won’t be told to pay thousands of dollars to get into an ambulance. All of that goes away.”

Average premiums for Californians who get insurance through an employer (as the majority of people in the state do) were just under $600 per month in 2016, according to the California Health Care Foundation — higher than the national average.

But the new system would not eliminate those costs entirely.

“If you’re paying for health insurance right now through healthcare premiums and cost-sharing, you’d end up paying instead through taxes,” said Micah Weinberg, president of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. “There are some people who at the end of the day will end up paying more, others who will end up paying less.”

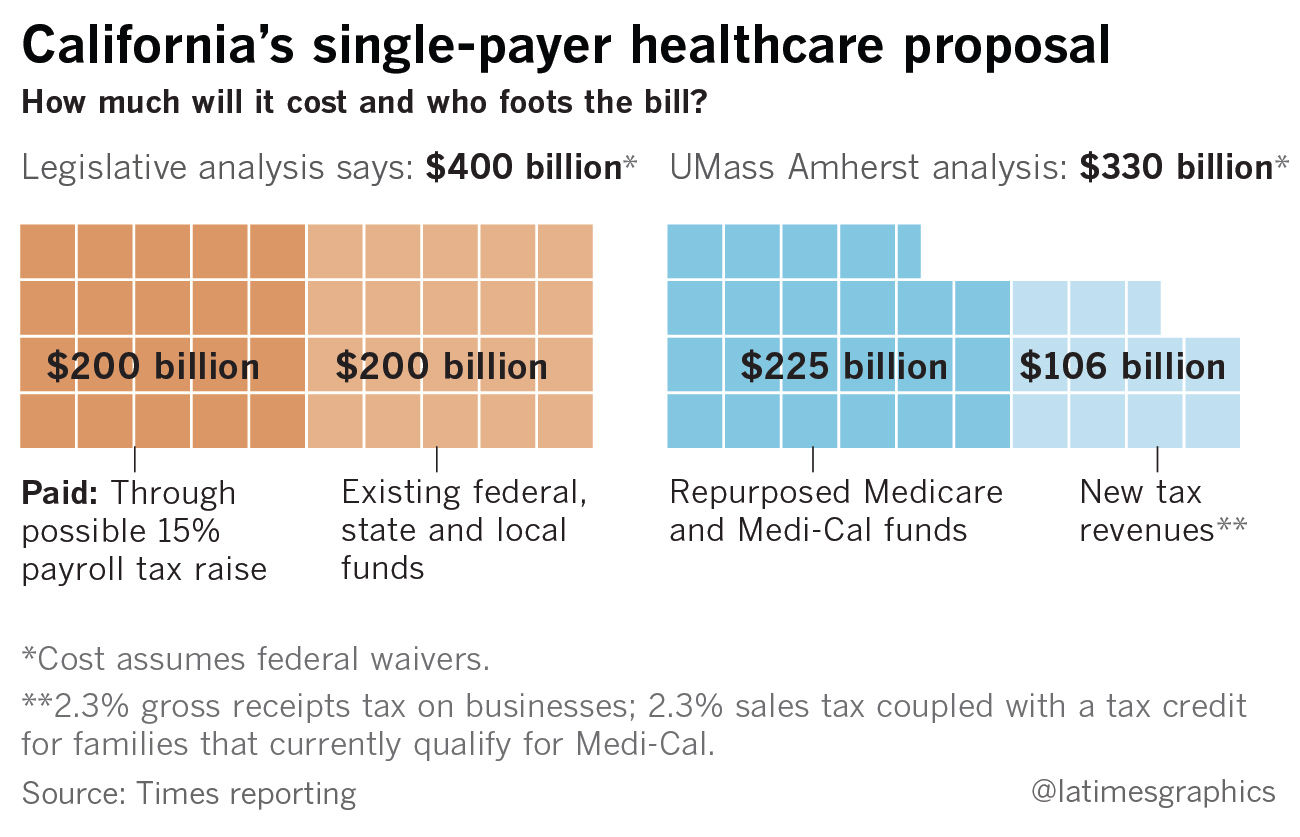

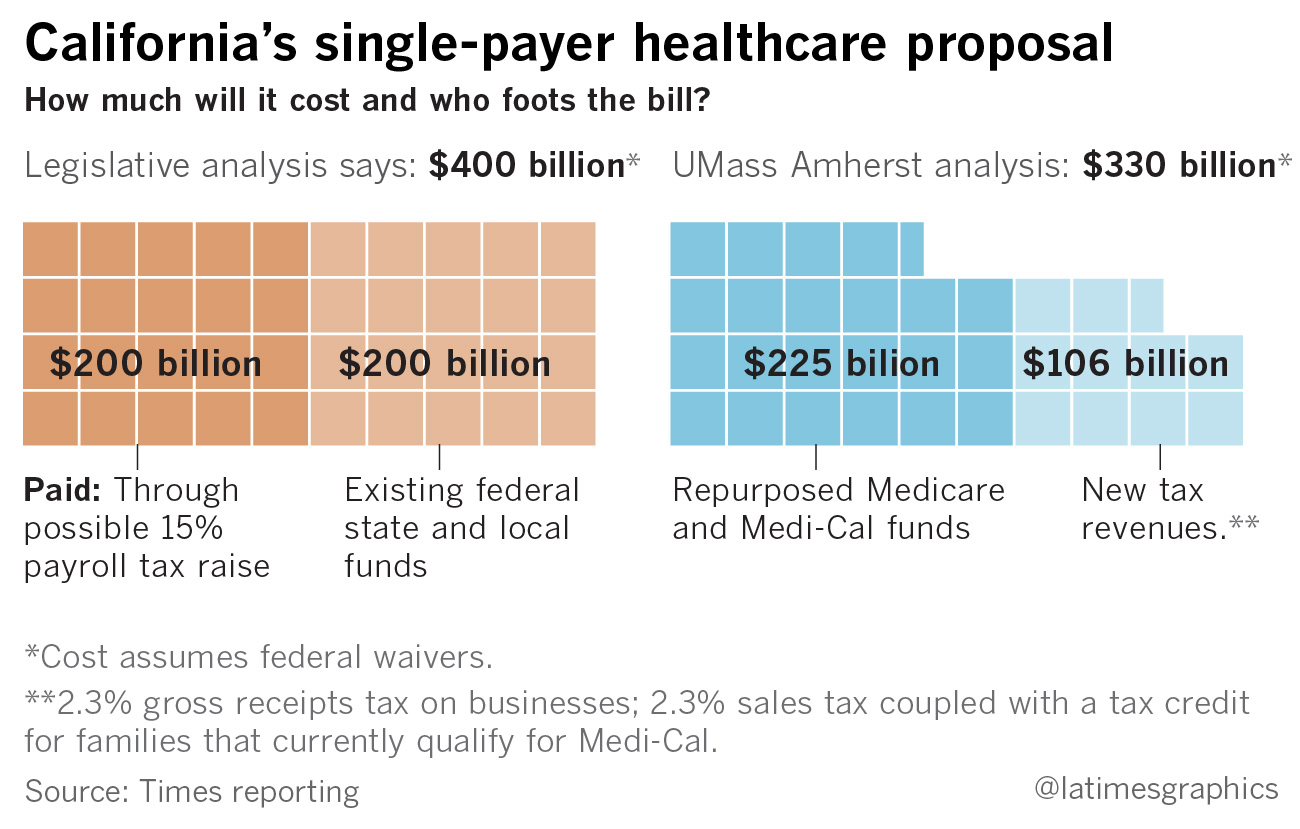

A recent state Senate analysis pondered a 15% payroll tax as a way to raise the estimated $200 billion needed in revenue to cover the program’s costs. The analysis assumes another $200 billion would come from existing federal, state and local funds.

The nurses’ union paid for their own study of the proposal, conducted by economics professors at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Assuming federal waivers, the analysis suggests $225 billion could come from repurposed Medicare and Medi-Cal funds.

An additional $106 billion would have to come through new revenue. The study suggests two new taxes: a 2.3% gross receipts tax on businesses and a 2.3% sales tax coupled with a tax credit for families that currently qualify for Medi-Cal.

These ideas are all possible scenarios to generate new revenue, but the bill currently does not contain any specific tax provisions.

“It's not free healthcare. That's something people really need to understand,” Weinberg said. The key question, he added, is “do you pay the government or do you pay a private insurer?”

What about overall healthcare costs for the state?

- A legislative analysis estimated overall costs would be $400 billion per year.

- Proponents of the plan are touting savings from the single-payer system and have come up with a lower annual price tag: $330 billion.

The Senate analysis pegged the total cost for the plan at $400 billion per year. Half of that would come from existing money, the other half from new revenues such as a payroll tax. Because the plan would eliminate the need for California employers to spend money on their workers’ healthcare (an estimated $100 billion to $150 billion annually), the total new spending on healthcare shouldered by the state under the bill would range from $50 billion to $100 billion yearly.

The $400-billion price tag is more or less in line with what Kominski and other researchers at UCLA estimated was the total healthcare spending in California in 2016: around $370 billion. Around 70% of those expenditures were paid by taxpayer dollars, the study found.

The UMass Amherst analysis, commissioned by the nurses, suggested that a single-payer system would decrease overall healthcare spending in the state by 18%, thanks to streamlined administration and the possibility of negotiating for reduced prescription drug prices. The total annual tab, according to the study, would be around $330 billion.

Both estimates far exceed the $183 billion in total spending in next year’s state budget as proposed by Gov. Jerry Brown.

The measure would establish a Healthy California board, appointed by the governor and the Legislature, that would set rates on how procedures would be reimbursed and negotiate with providers.

An important question is how the system would pay for care. The Senate analysis says the bill as written would follow a “fee-for-service” model, in which doctors and hospitals would be paid based on the number of procedures or patient visits they bill for.

Such a model has been criticized for driving up costs since it gives an incentive for doctors to provide more — but not necessarily more effective — care. Over the last few decades, the healthcare industry has moved toward different payment models that are meant to encourage efficiency and better care coordination.

Health economists say a system where doctors and hospitals are paid on a fee-for-service basis, and patients have no cost restraints from premiums or co-pays, means it’s more likely that patients will seek more care.

The measure’s backers dispute the legislative analysis’ stance that the model would be purely fee-for-service. Their commissioned study said that alternate payment methods to hospitals and reduced pharmaceutical costs through a formulary or price controls could rein in overuse of care.

There are other unknown costs, and they could be substantial. The analysis, for example, notes that the development of information technology systems to administer such a program could cost billions.

“Anybody who says they know how much this program is going to end up costing is rather optimistic,” Lakdawalla said. “This is a sea change in the way healthcare would be organized in California.

I work in the healthcare industry. How would this affect my job?

- There may be more time for patients instead of dealing with billing for doctors, but it could also affect their paycheck.

- Those who work at insurance companies or other administrative posts may lose their jobs.

For healthcare providers such as doctors and nurses, single-payer supporters say the proposed system would mean more time treating patients and less time navigating the complex world of insurance preauthorizations and reimbursements.

“Doctors would no longer have to deal with...hundreds of payers,” Lighty said. “You now have a single payer who will pay reliably or swiftly.”

Depending on how the program decides to reimburse for care, that could affect how much providers get paid. Lighty said the program would likely use the same rates as Medicare, which is less than what commercial insurers pay but more than Medi-Cal.

“Imagine what will happen if physician reimbursements fell by 15 to 20%, and those same reimbursements did not fall in Washington, Oregon, Arizona — [states that] are not implementing single-payer,” Lakdawalla said. “What happens to the population of doctors practicing in California?”

There’d be more upheaval for those who work in the insurance industry. Since the program would virtually eliminate the role of private insurance in the state’s healthcare market, the Senate analysis predicts that those workers “and many individuals who provide administrative support to providers would lose their jobs.”

The bill would authorize job retraining programs for workers affected by the change.

One year later: A physician’s letter to Medicare patients

by Rebekah Bernard, M.D. - Physician - December 28, 2016

Dear patients,

One year ago, I wrote to you about my concerns for the future of my practice in light of upcoming changes to the Medicare system. I explained my anxiety about the Medicare Access and CHIPS Reauthorization Act (MACRA), a change in fee structure from fee-for-service (I treat you in the office, submit the bill to Medicare, and they pay the bill), to “value-based” payment (I treat you in the office, submit the bill to Medicare, and they decide if my care provided adequate value to warrant payment).

This payment change guarantees to financially penalize 50 percent of Medicare providers, mostly solo and small practice doctors, just by nature of design. It works like this: Medicare allots a set pool of money to pay doctors. Payment occurs on a scale, with the “best” doctors (those who provide the best value, per Medicare) getting paid more, while the remainder are penalized with less money. “Value” is determined by physician reporting of various data points, like diabetes control and cholesterol medicine use. Doctors must either do this extra reporting during their free time, or hire additional staff to act as data entry clerks, just to avoid a financial penalty.

In addition to data reporting, physicians are graded by the dauntingly vague concept of “resource utilization.” This means that doctors will become accountable for patient outcomes, with financial penalties if their patients end up in the emergency room or readmitted to the hospital. Somehow, doctors are now responsible for ensuring that patients make the right choices, like smoking cessation and taking their medications, all the while attempting to maintain the highest patient satisfaction scores, since patient “experience” also contributes to the payment/penalty calculation.

This additional reporting and superhuman level of expectation demanded by MACRA just adds to the growing burden of administrative responsibilities faced by physicians. The increase in bureaucracy , often coming from the demands of insurance companies and Medicare, is a major cause of physician burnout, causing many doctors to contemplate leaving the practice of medicine entirely.

And I get this urge to leave clinical medicine. As I spent hours reviewing Medicare’s 2400-page final ruling on MACRA, set to begin just a few short months from the release of the report, I felt a sense of hopelessness and despair. How could I ever comply with the ever-growing list of requirements demanded of me, on top of the time that I needed to spend with my patients?

And so I made a difficult decision. I have decided to opt-out of Medicare, acknowledging that I can no longer play a game that is rigged against me; one that I can never win because of constantly changing rules, and one where the stakes include fines and even potential jail time.

And in leaving the current broken system, I will take my chances in a brave new world that hopes to return to the foundation of medicine: the physician-patient relationship.

I am returning to a time before insurance companies and Medicare, when doctors wrote their notes for themselves rather than for bean-counters. And while I will be using an electronic record rather than a 5 x 8-inch index card as many old-school physicians once did, my notes will be succinct and differential diagnosis-based, not cluttered by meaningless information entered merely to earn a payment bonus or avoid a penalty.

I am getting back to a time when medical decisions were made between the patient and the doctor, rather than by third-party mandates. And in eliminating those third-party payers, I am recreating a system that allows doctors the time they need, face-to-face with patients, to make those important health decisions. I will no longer require hours of time on needless paperwork, or have to pay an entire team of staff to handle the minutiae while I maintain a breakneck 7-minute-per-patient visit schedule, just so I can pay my overhead.

As of January 1, 2017, I am no longer a part of the conventional Medicare system. And as hard as this transition may be, it’s a no-brainer when compared with the option of staying in a system that has led to catastrophic levels of burn out, depression, and physician suicide. I am taking back control. I am direct care.

The Specialists’ Stranglehold on Medicine

by Jamie Kourman - NYT - June 4, 2017

Republicans are trying to cut health care spending. But hacking away at Medicaid, weakening coverage requirements and replacing Obamacare’s subsidies with a convoluted tax credit will not deal with the real crisis in American health care.

The Affordable Care Act was misnamed; it should have been called the Access to Unaffordable Care Act. In 2015 health care spending reached $3.2 trillion — $10,000 for every man, woman and child in America. While our health care system is the most expensive in the world by far, on many measures of performance it ranked last out of 11 developed countries, according to a 2014 Commonwealth Fund Report.

But deregulation will not fix it. To the extent that we can call it a market at all, health care is not self-correcting. Instead, it is a colossal network of unaccountable profit centers, the pricing of which has been controlled by medical specialists since the mid-20th century. Neither Republicans nor Democrats have been willing to address this.

Most Americans mistakenly believe that they must see specialists for almost every medical problem. What people don’t know is that specialists essentially determine the services that are covered by insurance, and the prices that may be charged for them.

Physician specialty groups have created “societies” to provide education, establish clinical guidelines and handle public relations. These range from the Society of Surgical Oncology to the group that represents me and my ear, nose and throat colleagues, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. They are also lobbyists, charged with maximizing the incomes of member doctors by influencing pricing decisions made by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Those prices become the benchmarks for private health insurancecompanies, too.

There are so many specialty organizations because each develops authority over a niche market and vigorously guards its turf. Imagine building a house by allowing each workman to do his own thing. The plumber would put a sink in every room. The electrician would install chandeliers on every ceiling. The carpenter would panel every room in luxurious wood. That’s how health care works.

Though they would vigorously deny it, entrepreneurial doctors often treat each patient as an opportunity to make money. Research shows that physicians quickly adapt their treatment choices if the fees they get paid change. But the current payment incentives do more than drive up costs — they can kill people.

Sedated endoscopy, for example, which is used by gastroenterologists to treat conditions like acid reflux and to perform colonoscopies, carries significant risks of adverse effects, including mortality. Joan Rivers’s death from the procedure was not a one-in-a-million complication. Reported death rates vary considerably, but one rigorous study suggests that the death rate is 1 in 9,000. Since approximately 18 million sedated endoscopies are done each year in the United States, “routine endoscopies” may cause 2,000 deaths a year.

And yet, for acid reflux, there is a safer, cheaper and equally accurate procedure available called transnasal endoscopy; unfortunately, doctors rarely employ it, presumably because it doesn’t pay as well.

The focus of my practice is acid reflux that affects the nose, throat and lungs, so-called respiratory reflux. By the time patients arrive at my office, most have already seen otolaryngologists, pulmonologists, gastroenterologists and allergists. They have undergone unnecessary CT scans, MRI’s, blood work, allergy tests, asthmatreatments, endoscopies, and nasal and sinus surgeries. Each specialist performs the procedures that generate income for them, and then passes the patient along.

But when it comes to managing acid reflux, specialists offer no advantage over primary care physicians. Indeed, sometimes all a patient needs are basic changes in diet, lifestyle and sleep.

Neither the Affordable Care Act nor the Republicans’ American Health Care Act addresses the way specialists are corrupting our health care system. What we really need is what I’d call a Health Care Accountability Act.

This law would return primary care to the primary care physician. Every patient should have one trusted doctor who is responsible for his or her overall health. Resources must be allocated to expand those doctors’ education and training. And then we have to pay them more.

There are approximately 860,000 practicing physicians in the United States today, and too few — about a third — deliver primary care. In general, they make less than half as much money as specialists. I advocate a 10 percent to 20 percent reduction in specialist reimbursement, with that money being allocated to primary care doctors.

Those doctors should have to approve specialist referrals — they would be the general contractor in the building metaphor. There is strong evidence that long-term oversight by primary care doctors increases the quality of care and decreases costs.

The bill would mandate the disclosure of procedures’ costs up front. The way it usually works now is that right before a medical procedure, patients are asked to sign multiple documents, including a guarantee that they will pay whatever is not covered by insurance. But they will have no way of knowing what the procedure actually costs. Their insurance may cover 90 percent, but are they liable for 10 percent of $10,000 or $100,000?

We also need more oversight of those costs. Instead of letting specialists’ lobbyists set costs, payment algorithms should be determined by doctors with no financial stake in the field, or even by non-physicians like economists. An Independent Payment Advisory Board was created by Obamacare; it should be expanded and adequately funded.

Finally, the bill would create an online database, reporting all physician conflicts of interest, as well as information on how many procedures each doctor performs, with related morbidity and mortality data.

If the president and Congress are serious about getting health care costs under control, this is a starting point. If there ever was an area where bipartisanship might triumph, it would be reining in a corrupt health care system that grows like a cancer on our country.

Obama Unwittingly Handed Trump a Weapon to Cripple the Health Law

by Carl Hulse - NYT - June 4, 2017

WASHINGTON — Obama administration officials knew they were on shaky ground in spending billions of dollars on health insurance subsidies without clear authority. But they did not think a long-shot court challenge by House Republicans was cause for deep concern.

For one thing, they would be out of office by the time a final ruling in the case, filed in 2014, was handed down. They also believed that a preliminary finding against the administration would ultimately be tossed out. Finally, they figured that President Hillary Clinton could take care of the problem, if necessary.

Well, they are out of office, Mrs. Clinton is not president and the uncertain status of the cost-sharing payments now looms as the biggest threat to the stability of the insurance exchanges created under the Affordable Care Act. A dubious decision made by the previous White House has handed the current administration a powerful weapon to wield against the health care legislation that it despises.

“The administration should not have found an appropriation where none existed,” said Nicholas Bagley, a University of Michigan law professor who has studied and written about the issue. “The Obama administration argument that the Affordable Care Act included an appropriation for the cost-sharing payments never held water.”

Judge Rosemary M. Collyer agreed with that assertion last year. She ruled that the Obama administration had no explicit authority to pay as much as $130 billion over 10 years to insurance companies to cover out-of-pocket health costs for millions of lower-income Americans obtaining insurance on the new health exchanges. At the same time, she found that the Republican-led House had the standing to sue the administration — a potentially far-reaching decision that many constitutional law experts predicted would be overturned on appeal, causing the suit to be dismissed.

Then November’s election upended all the calculations. Donald J. Trump won, and his interest in defending the executive branch against the House lawsuit was nonexistent given his antipathy for the health care law.

But neither he nor congressional Republicans were in any hurry to drop the appeal initiated by the Obama administration because that would mean the subsidies would be immediately cut off, throwing the health insurance market into turmoil. Instead, the lawsuit has been essentially suspended and the payments have become a new bargaining chip in Washington. The administration is essentially doling them out on a month-to-month basis while Republicans struggle to come together on their own health care replacement plan.

Republicans say the fight over the subsidies is just one element contributing to a failure of the health care law.

“This law is in the middle of a collapse,” Speaker Paul D. Ryan told reporters before the House went on its Memorial Day break. “We need to bring down the cost of coverage, and we need to revitalize the market so that people have real choices and real access to affordable health care.”

Democrats and other critics say it is the Trump administration’s position on the cost-sharing payments that is a chief contributor to the shakiness in the market, with insurers abandoning the program or raising premiums in anticipation of the federal dollars disappearing. They say that the White House maneuvering on the subsidies is simply the latest in a series of calculated moves meant to sabotage the insurance program, starting with an order to end enforcement of the requirement that people obtain insurance.

While some Democrats acknowledge that the Obama administration left the law vulnerable to attack with the way it funded the subsidies, they say it is Republicans who will now pay politically if the program collapses on their watch.

“This would put their hands on the bloody knife,” said Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland, who is heading the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee.

Mr. Bagley, the law school professor, agrees that Republicans would be held accountable for a failure in the marketplace. He says they should be because of the actions they have taken to undermine it.

“The biggest source for the instability in the markets in 2018 is the president,” he said, warning of a run of damaging headlines for Republicans beginning this fall if things proceed on their current course.

Republicans dismiss such talk and say that the public knows just where the problems with the health care law originated — and it is not with them.

“The blame belongs with Obamacare,” Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader, said recently. “There’s just no serious way to now try and spin away these years and years of Obamacare failures on cost.”

The ongoing debate overlooks an underlying problem with the Affordable Care Act. In the past, disputes such as the funding fight would have been resolved with corrective legislation.

Congress has traditionally taken years to resolve disagreements and unintended consequences arising from complex pieces of social legislation, as they continue to do with Medicare, which became law in the 1960s. But the bitter partisan divide over health care has prevented any such tweaking.

What to do about the payments will no doubt arise in budget talks between Capitol Hill and the White House.

The Trump administration could try again to extract concessions from Democrats by trading a commitment to continue funding the subsidies even though the White House was unsuccessful in doing so this year.

And if the Republican effort to find a substitute to the health care law ends in failure, which now seems a real possibility, perhaps Republicans and Democrats could find a way to come together to make repairs to the Affordable Care Act and resolve doubts surrounding the payments.

But for now, the uncertainty continues to imperil both the Affordable Care Act and the politicians who could be held accountable for any failure.

Rebuking Congress, Cuomo Plans to Keep State Health Care Plans Intact

by Jesse McKinley - NYT - June 4, 2017

ALBANY — Striking pre-emptively at an increasingly frequent foil, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo plans to announce a series of steps on Monday to safeguard insurance coverage against a possible repeal of all or parts of the Affordable Care Act in Washington.

The measures, taken via emergency regulations, will include requiring any private company doing business on the state’s insurance marketplace to guarantee the 10 “essential health benefits” required by President Barack Obama’s signature 2010 health care law. The governor will also direct the state’s health department to block any company that withdraws from the exchange from participating in Medicaid or its children’s health plan.

In a statement, the governor, a Democrat, said that “health care is a human right,” noting that he had also firmed plans to ensure contraceptive and abortion protections, something he initially outlined in January.

“With Washington trying to take a wrecking ball to our health care system, we are taking concrete steps to ensure core protections of the Affordable Care Act remain intact,” Mr. Cuomo said, adding that he would direct his Department of Financial Services to prevent any discrimination based on gender, age or pre-existing conditions, a politically charged topic in the health care debate. “New Yorkers will continue to have access to the quality medical care they need and deserve.”

The threat of a possible repeal of the Affordable Care Act, commonly known as Obamacare, has increased in recent weeks following the passage of a Republican replacement plan in the House of Representatives. That bill’s fate, however, is less than certain in the Senate. The House plan would allow states to opt out of the 10 essential benefits, which include things like hospitalization, maternity and pediatric care, lab work, and mental health and addiction services.

And while such benefits would seem unlikely to be revoked in New York — a solidly Democratic outpost — experts say that actions such as Mr. Cuomo’s are clearly meant to codify the state’s opposition to President Trump’s push to dismantle Obamacare.

“It’s a not a shock, but it sends a signal,” said Larry Levitt, a policy expert at the Kaiser Family Foundation, noting that New York traditionally took a heavy hand in regulating the insurance market. He added, “It puts down a marker that New York is solidly behind the consumer protections in the A.C.A.”

Indeed, the action on health coverage comes just days after Mr. Cuomo, a man with possible presidential ambitions, reacted to another of President Trump’s high-profile policy moves: the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris climate accord.

Shortly after the president’s remarks, Mr. Cuomo said that New York would continue to abide by that agreement’s strictures on greenhouse gases, forming a coalition with other states as similar actions were adopted by cities and companies.

Mr. Cuomo, a political centrist who is up for re-election next year, has proffered a number of other actions meant to solidify his progressive reputation in recent months, including a plan for tuition-free college education, an idea developed on the national stage by Senator Bernie Sanders.

The governor also plans to announce a ban preventing insurers that withdraw from the state health markets from contracting with state agencies and entities.

State officials say that more than one million New Yorkers now have insurance as a result of the Affordable Care Act, and more than a dozen private insurers currently participate in the state’s exchange. Under the governor’s action, those companies could be boxed out of the state’s Medicaid program — one of the nation’s most generous — if they drop out of the health care marketplace.

Mr. Levitt said that such a move was meant to increase New York’s leverage over companies, adding that he expected that other states, particularly those run by Democrats, would consider such actions. “We’re likely to start hearing more from governors on health care as the Senate ramps up debate,“ he said.

The Senate's 4 Big Problems With Health Care

by Susan Davis - Maine Public - June , 2017

Republicans are running way behind schedule.

In the dream scenario outlined by party leaders back in January, President Trump would have signed legislation to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, months ago. By early June, Republicans were supposed to be in the thick of overhauling the tax code.

Here's the reality: The GOP health care debate is stalled in Congress, and its uncertainty has clogged up the legislative pipeline to Trump's desk. Republicans can't move on — and many are ready to do so — until they resolve the fate of their long-promised health care bill.

Here are four big problems standing in the way.

1. Lack of momentum

"I don't see a comprehensive health care plan this year," Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., told a local TV station on Thursday.

Nearly a month after the House passed its version of the health care bill, 13 GOP senators have had weeks of closed-door meetings but so far have failed to produce any discernible progress on health care. The one piece of consensus is that the House-passed American Health Care Act is a non-starter in the Senate.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., was candid about the bill's status in an interview with Reuters before the Memorial Day break. "I don't know how we get to 50 [votes] at the moment. But that is the goal. And exactly what the composition of that [bill] is I'm not going to speculate about because it serves no purpose," McConnell said.