Finally, Something Isn’t the Matter With Kansas

by Michael Tomasky - NYT - June 12, 2017

The most momentous political news of the past week? For my money, it wasn’t James Comey’s Senate testimony, riveting as it was. It was the Kansas Legislature’s decision to defy the governor and raise income taxes — a move that could well be the first step in a transformation of American politics much more far-reaching than anything that could come from Russiagate.

Hear me out. Kansas, under Gov. Sam Brownback, has come as close as we’ve ever gotten in the United States to conducting a perfect experiment in supply-side economics. The conservative governor, working with a conservative State Legislature, in the home state of the conservative Koch brothers, took office in 2011 vowing sharp cuts in taxes and state spending, except for education — and promising that those policies would unleash boundless growth.

The taxes were cut, and by a lot. The cumulative cut was forecast to be $3.9 billion by 2019. A fellow at a right-leaning Missouri think tank said in 2015 that Mr. Brownback’s cuts were “the biggest tax cut of any state, relative to the size of its economy, in recent history.”

The cuts came. But the growth never did. As the rest of the country was growing at rates of just above 2 percent, Kansas grew at considerably slower rates, finally hitting just 0.2 percent in 2016. Revenues crashed. Spending was slashed, even on education: In March, the State Supreme Court ruled that state-level school spending was unconstitutionally low. The court is ideologically mixed, but its ruling was unanimous.

The experiment has been a disaster. Mr. Brownback is widely disliked. If he has anything to be grateful for, it’s the existence of Gov. Chris Christie, Republican of New Jersey, who recently swiped from him the title of the nation’s most unpopular governor, which Mr. Brownback had held for the better part of three years.

Finally, even the Republican Kansas Legislature faced reality. Earlier this year it passed tax increases, which the governor vetoed. Last Tuesday, the legislators overrode the veto.

Not only is it a tax increase — it’s even a progressive tax increase! A married couple filing jointly and earning $30,000 will pay an additional $120, which is 0.4 percent of total income, while the same couple earning $100,000 will fork over $755, or 0.755 percent. More than half of the Republicans in both houses voted for the increases.

There’s the background. Now, why is this a big deal?

Because Republicans are not supposed to raise taxes, ever. In Washington or in the states. This goes back to President George H. W. Bush’s agreeing to a bipartisan tax increase in 1990 after famously saying in his 1988 campaign, “Read my lips: no new taxes.” Afterward, the conservative group Americans for Tax Reform, led by Grover Norquist, started making Republican candidates for Congress and state houses sign a no-tax pledge.

Ever since, with scattered exceptions, no Republican member of the House or Senate has voted for a tax increase. For 27 years. If you wonder why problems arise and Congress never does anything about them, the tax pledge is usually the answer, or at least an answer.

Think we need to build bridges and roads and lay freight rail lines? Of course we do. But we can’t. It would require a tax. Think rural Americans need better access to broadband? You bet they do. But doing it right would need a tax. Think we ought to be spending far, far more than we are currently on this hideous opioid crisis, with drug overdoses now being the leading cause of death for Americans under 50? We most surely ought to be. But no — gotta pass those tax cuts.

The Republican no-tax position even bears a share of the blame for our current polarization. Republicans once recognized the principle that public purposes sometimes justified the raising of additional revenue. They might have balked at the specific number the Democrats proposed, but they accepted that taxes were negotiable.

This made compromise possible. The agreement between President Ronald Reagan and Speaker Tip O’Neill in 1983 to save Social Security? It’s a famous deal, among insiders, who point to it often as they lament the lost art of the horse trade. It involved benefits cuts — an increase in future retirement ages — and increases in the payroll tax.

Why can’t they make those kinds of deals today, you ask, for any number of issues? It’s not because there’s something in the water. It’s not because of cable news, or social media or even the corrupting influence of big money in politics. It’s because Republicans won’t agree to a penny in tax increases of any kind — income taxes, payroll taxes, the gasoline tax, anything.

So here’s hoping that Kansas represents a breakthrough moment. The effects of our failure to invest in ourselves are all around us. Change won’t come fast — for one thing, very few Americans know the above, because no one talks about it (hello, Democrats). But at least for now we can say, for the first time in a long time, that something finally isn’t the matter with Kansas.

Editor's Note:

The preceding story about an increase in taxes in Kansas is instructive. Public goods require public financing - in other words, taxes. Health care as a right, or universal public good, will also require tax increases.

We should be candid in acknowledging that reality, and explaining why taxes in some circumstances are, the simplest, most enforceable and fairest way to finance them. Think public schools, libraries, roads, police, firefighters, judiciary, legislatures and yes, health care!

Oliver Wendell Holmes once rightly said "Taxes are the price of civilization."

- SPC

The Senate Hides Its Trumpcare Bill Behind Closed Doors

byThe Editorial Board - NYT - June 13, 2017

A coterie of Republicans is planning to have the Senate vote before July 4 on a bill that could take health insurance away from up to 23 million people and make changes to the coverage of millions of others. And they are coming up with the legislation behind closed doors without holding hearings, without consulting lawmakers who disagree with them and without engaging in any meaningful public debate.

There is no mystery why the Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell, is trying to push this bill through quickly. The legislation would repeal major provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Opening it to scrutiny before a vote would be the congressional equivalent of exposing a vampire to sunlight.

That is one mistake Mr. McConnell, a master of the Senate’s dark arts, is not about to make. As one Republican aide put it to Axios on Monday, “We aren’t stupid.” Better to pass a terrible bill in the cover of darkness just as the House did with its version, the American Health Care Act, in the hopes that critics do not have much time to raise a stink. And then there is President Trump, who is standing ready to applaud whatever turkey the Senate produces as long as it gives him a chance to claim a win.

Mr. McConnell’s strategy belies the disingenuous Republican complaint that Democrats jammed the A.C.A., or Obamacare, into law in 2010 without sufficient analysis or discussion. The Republican effort to undo the A.C.A. bears no resemblance whatsoever to that much more thorough exercise. Congress and the Obama administration spent a year on health care reform from March 2009 to March 2010. The House and Senate came up with several competing bills, held dozens of hearings, accepted Republican amendments and spent countless hours soliciting feedback from public interests groups and the health care industry. The Congressional Budget Office produced several reports to analyze the various proposals and the legislation that ultimately became law.

By contrast, instead of public drafts and hearings, we now have to settle for a series of leaks from Capitol Hill about what is or isn’t in the bill. On one day, news organizations might be told that Mr. McConnell’s health care working group (which happens to be composed entirely of men) has found ways to win over more moderate senators like Rob Portman of Ohio by agreeing to phase out the expansion of Medicaid more slowly than the House bill would. Such a policy would mean that millions would still lose coverage but not as quickly as in the House version.

But on another day, the public might learn that conservatives like Rand Paul of Kentucky are furious because the draft does not do enough to turn the American health care system into a facsimile of “The Hunger Games.”

In other words, the country is getting only glimpses of half-formed policies and mere hints of the back-room deals offered to win support for them. The Washington Post recently reported, for instance, that Mr. McConnell might cobble together a slim majority for his bill by offering senators from Appalachian states a fund for the opioid epidemic. He might also have to come up with something to accommodate Lisa Murkowski of Alaska because her state has high health care costs and stands to lose a lot if Congress reduces spending on health care by $1.1 trillion over 10 years to give the wealthiest American families a fat tax cut.

It would be tempting to find all this negotiating a purposeless charade if it didn’t have the potential to hurt millions of people and wasn’t already taking a toll. In recent weeks, health insurers have ended coverage in some parts of the country for next year and proposed raising premiums substantially elsewhere. The companies say they are trying to protect themselves from the uncertainty around the A.C.A. Blame for that rests with Congress and Mr. Trump, who has threatened to destroy Obamacare through administrative changes.

Republican leaders seem to think they will gain a tactical legislative advantage if they can negotiate a deal behind the scenes and then suddenly spring it on the full Senate. Those gains will quickly evaporate when voters learn what they have done.

The Halfhearted Opposition to the G.O.P.’s Health Care Misery

by David Leonhardt - NYT - June 13, 2017

The Republican health care bill now sneaking its way through the Senate has a good chance of becoming law, even though it would do miserable damage. And it has a good chance partly because some of the bill’s most influential opponents have not had the courage of their convictions.

I realize that sounds harsh. These opponents generally have good intentions. But they haven’t been very effective so far, and they don’t have much time to summon the courage to become more effective.

The opponents I’m talking about include almost every major health care interest group: the lobbying groups for doctors, nurses and hospitals as well as advocates for patients with cancer, diabetes, lung disease, heart disease or birth defects. Each understands that the bill would deprive millions of Americans of insurance. Each has criticized the bill, and some, including AARP, have done more, like organizing phone calls.

But they have not come close to the sort of public campaign that would put intense pressure on senators. History shows what such a campaign would look like:

In the 1940s, the American Medical Association (which represents doctors) conducted what was then “the most expensive lobbying effort in American history,” according to Paul Starr, author of a Pulitzer-winning history of health care. The campaign changed public opinion about Harry Truman’s plan for national insurance, helping doom it.

In the 1960s, the same association hired a movie star by the name of Ronald Reagan to barnstorm the country denouncing the proposal for Medicare. It would be the start of socialism, Reagan warned, and “invade every area of freedom as we have known it.” He lost that battle, but it set in motion his political career and modern conservatism.

In the 1990s, the lobbying group for insurance companies ran an ad campaign featuring a fictional couple named Harry and Louise. Sitting at their kitchen table “sometime in the future,” they lamented how much worse their coverage had become. The ads helped defeat Bill Clinton’s plan.

Today, however, “there isn’t much of a campaign,” as Starr told me. “And it contrasts very dramatically with some of the earlier conflicts.”

If anything, the case for an aggressive campaign is stronger now. Virtually every big health care group views the Republican plan as a disaster, one that would harm many Americans largely in the service of cutting taxes for the wealthy.

But much of the groups’ criticism — like “a drastic step backward” — has come via news release. There has been no Harry, no Louise and no Ronald Reagan to capture national attention. “It’s a really big problem,” a Senate Democratic aide said. “It’s important right now that these groups start to mobilize much more than they have.”

The passivity has played into the Republican strategy. House and Senate leaders have taken the radical step of writing a bill largely in secret, without hearings. So health care groups haven’t been able to testify publicly. Without hearings — and without a publicity campaign — Congress has not felt enough political heat. Grass-roots groups have admirably tried to create heat, at town hall meetings and elsewhere, but it hasn’t been enough.

Why haven’t the big lobbying groups done more? I think there are two main answers. First, in past campaigns, groups were largely defending their own financial interests. People fight hard when their own money is at stake. Today’s opposition is at least as much about principle as profit, and lobbying groups haven’t been willing to go all-out for principle.

Second, the groups are wary of attacking the Republican Party, given its current power. “We’re living in a world in which it’s just Republican votes,” one lobbyist told me. Speaking loudly against the bill risks alienating powerful politicians — and risks making the health care groups look partisan.

I get their reluctance. I feel a pang of discomfort every time I describe the radicalismof today’s Republican Party. I also know that the groups are lobbying behind the scenes for changes that would make the bill marginally less bad.

But that’s not nearly enough.

Doctors, hospital executives and treatment advocates take pride in doing good work that improves people’s lives. Sometimes, good work doesn’t require hard choices. Other times, it does. This is one of those times when it does. A halfhearted effort to stop the bill won’t protect millions of Americans from losing their insurance and, ultimately, from being denied medical care.

Senate leaders are rushing to pass a bill before their July 4 recess, and they seem to be making headway. That leaves opponents only three weeks to live up to their convictions. They can create advertisements that make clear the human damage the bill would do. Or put their well-respected leaders on popular talk shows. Or hold a mock hearing, featuring every group that has been denied the ability to testify.

Above all, they can take a risk for a cause.

You’re Probably Going to Need Medicaid

by David Grabovski, Jonathan Gruber and Vincent Mor - NYT - June 13, 2017

Imagine your mother needs to move into a nursing home. It’s going to cost her almost $100,000 a year. Very few people have private insurance to cover this. Your mother will most likely run out her savings until she qualifies for Medicaid.

This is not a rare event. Roughly one in three people now turning 65 will require nursing home care at some point during his or her life. Over three-quarters of long-stay nursing home residents will eventually be covered by Medicaid. Many American voters think Medicaid is only for low-income adults and their children — for people who aren’t “like them.” But Medicaid is not “somebody else’s” insurance. It is insurance for all of our mothers and fathers and, eventually, for ourselves.

The American Health Care Act that passed the House and is now being debated by the Senate would reduce spending on Medicaid by over $800 billion, the largest single reduction in a social insurance program in our nation’s history. The budget released by President Trump last month would up the ante by slashing another $600 billion over 10 years from the program. Whether the Senate adopts cuts of quite this magnitude or not, any legislation that passes the Republican Congress is likely to include the largest cuts to the Medicaid program since its inception.

Much focus has rightly been placed on the enormous damage this would do to lower-income families and youth. But what has been largely missing from public discussion is the radical implications that such cuts would have for older and disabled Americans.

Medicaid is our nation’s largest safety net for low-income people, accounting for one-sixth of all health care spending in the United States. But few people seem to know that nearly two-thirds of that spending is focused on older and disabled adults — primarily through spending on long-term care services such as nursing homes.

Indeed, Medicaid pays nearly half of nursing home costs for those who need assistance because of medical conditions like Alzheimer’s or stroke. In some states, overall spending on older and disabled adults amounts to as much as three-quarters of Medicaid spending. As a result, there is no way that the program can shrink by 25 percent (as under the A.H.C.A.) or almost 50 percent (as under the Trump budget), without hurting these people.

A large body of research, some of it by us, has shown that cuts to nursing home reimbursement can have devastating effects on vulnerable patients. Many nursing homes would stop admitting Medicaid recipients and those who don’t have enough assets to ensure that they won’t eventually end up on Medicaid. Older and disabled Medicaid beneficiaries can’t pay out of pocket for services and they do not typically have family members able to care for them. The nursing home is a last resort. Where will they go instead?

Those who are admitted to a nursing home may not fare much better. Lowering Medicaid reimbursement rates lead to reductions in staffing, particularly of nurses. Research by one of us shows that a cut in the reimbursement rate of around 10 percent leads to a functional decline of nursing home residents (that is, a decline in their ability to walk or use the bathroom by themselves) of almost 10 percent. It also raises the odds that they will be in persistent pain by 5 percent, and the odds of getting a bedsore by 2 percent.

Finally, these cuts would just shift costs to the rest of the government. Lower-quality nursing home care leads to more hospitalizations, and for Americans over 65, these are paid for by another government program, Medicare. One-quarter of nursing home residents are hospitalized each year, and the daily cost of caring for them more than quadruples when they move to the hospital. Research shows that a reduction in nursing home reimbursements of around 10 percent leads to a 5 percent rise in the odds that residents will be hospitalized. So care for seniors suffers, and the taxpayer pays.

Mr. Trump and the Republicans would lower spending on the frailest and most vulnerable people in our health care system. They would like most Americans to believe that these cuts will not affect them, only their “undeserving” neighbors. But that hides the truth that draconian cuts to Medicaid affect all of our families. They are a direct attack on our elderly, our disabled and our dignity.

Single-Payer Health Care Is Doable

Letters to the Editor - NYT - June 13, 2017

To the Editor:

Re “Inching to Left, Democrats Push Universal Care” (front page, June 4):

You call single-payer a “government takeover of health care.” Later in the article, single-payer is referred to as that old canard “socialized medicine.”

Single-payer is simply where the government sets the price and the range of reimbursable procedures because it is the sole insurance provider — in other words, Medicare for all.

Medicare is extremely popular, and for good cause. It is administratively easy for both doctors and patients, the fees are reasonable, and access to doctors is straightforward.

And by the way, we do have a form of socialized medicine in this country; it’s called the V.A.

MYRA SAUL, SCARSDALE, N.Y.

To the Editor:

Re “Inching to Left, Democrats Push Universal Care” (front page, June 4):

You call single-payer a “government takeover of health care.” Later in the article, single-payer is referred to as that old canard “socialized medicine.”

Single-payer is simply where the government sets the price and the range of reimbursable procedures because it is the sole insurance provider — in other words, Medicare for all.

Medicare is extremely popular, and for good cause. It is administratively easy for both doctors and patients, the fees are reasonable, and access to doctors is straightforward.

And by the way, we do have a form of socialized medicine in this country; it’s called the V.A.

MYRA SAUL, SCARSDALE, N.Y.

To the Editor:

Americans will consider single-payer health care when proponents start thinking like marketers.

People don’t “buy” features; they buy benefits. Single-payer emphasizes a feature. Now the conversation is about the complexities of public financing, spiraling down into a discussion of taxes. Now you’re playing defense.

In contrast, start with “Medicare for all,” and you’re talking about benefits. Republican and Democratic Medicare recipients are with you. You’ve got a cohort of fans who happen to be the most likely voters.

Medicare for all eliminates lifetime limits, pre-existing conditions and private insurers’ interference in decisions about your medical care. It leverages the purchasing power of 325 million Americans to buy health care services at lower prices.

Medicare is privately delivered health care. Private doctors and hospitals simply bill a single government body instead of myriad insurance companies. Benefits for you, benefits for your doctor. You have more choice, because every provider is “in network.”

“Medicare for all” eliminates the middlemen: the profit-driven insurance bureaucracies that contribute nothing to our country’s health except higher costs.

Put the focus where it belongs: on benefits.

JOANNE CURRIE, PITTSBURGH

To the Editor:

The New York State Assembly passed a universal, single-payer health care plan last month by a vote of 94 to 46, and it has 31 co-sponsors in the 63-member Senate (New York Health Act S. 4840/A. 4738).

You say single-payer has a slim chance of passing “only in California.” But the only thing stopping it in New York is convincing one more senator and getting it through the obstructionist Senate leadership.

Public outcry might well accomplish this. The time is now, as the Legislature meets for only two more weeks this year.

JONATHAN REISS, NEW YORK

To the Editor:

We don’t have to look far to find a model of universal care. France’s program combines the elements desired by both American political parties. I call it a public-private partnership.

The French plan was created in 1945 and amended over time. The program, which is funded by taxpayers, establishes a health care budget for all citizens but doesn’t pay the full amount of care. The patient must pay the difference. People below a certain income are exempt from this responsibility. Patients may choose to see any licensed practitioner at any time without limit.

To make up the difference between what the government pays and the cost of care, most people buy a supplementary insurance policy on top of the basic government plan either through their employer or on their own. There is an extensive range of plans to meet individual circumstances.

Why doesn’t Congress investigate the French program to extrapolate elements that would come close to meeting the requirements of both Republicans and Democrats?

GARY LEFKOWITZ, CONGERS, NY

There’s No Magical Savings in Showing Prices to Doctors

by Aaron Carroll - NYT - June 12, 2017

Physicians are often unaware of the cost of a test, drug or scan that they order for their patients. If they were better informed, would they make different choices?

Evidence shows that while this idea might make sense in theory, it doesn’t seem to bear out in practice.

A recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine involved almost 100,000 patients, more than 140,000 hospital admissions and a random distribution of laboratory tests. During the electronic ordering process, half the tests were presented to doctors alongside fees. While the cost to the patient might vary, these Medicare-allowable fees were what was reimbursed to the hospital for the test or tests being considered. The other half of the tests were presented without such data.

The researchers suspected that in the group seeing the prices, there would be a decrease in the number of tests ordered each day per patient, and that spending on these tests would go down. This didn’t happen. Over the course of a year, there were no meaningful or consistent changes in ordering by the doctors; revealing the prices didn’t change what they did much at all.

This isn’t the first time a study like this found that showing prices to doctors doesn’t make a difference. Earlier this year, a study published in Pediatrics reported on a similar randomized controlled trial on physicians caring for children. In this case, doctors were randomized to one of three groups. The first group saw the median price of a test when they ordered it. The second saw both the price (often lower) when obtained within the current health care system and outside it. The third group saw no price at all.

Pediatric-focused clinicians showed no effect from price displays. Adult-focused clinicians actually ordered more tests when they saw the prices.

A similarly designed study of more than 1,200 clinicians in an accountable care organization published earlier this year also found no effects from telling physicians prices.

Some older studies have found that physicians might alter their behavior on individual tests, but in only five of the 27 they examined. Another found a small, but statistically significant, difference. Unfortunately, this study suffered from asymmetric randomization. Even before the intervention began, the tests chosen for the price-showing group were ordered more than three times as much as those chosen for the control group. More expensive tests appeared in the control group for some reason as well.

Of course, any one study has the potential to be an outlier or subject to limitations that might warrant skepticism. These can be minimized by looking at the body of evidence in systematic reviews.

One was published in 2015, and argued that in the majority of studies, giving physicians price information changes their ordering and prescribing behavior to lower the cost of care. A closer look, though, reveals that most of the studies in this analysis were more than a decade old. Many took place in other countries. And all were published before these latest, and largest, studies I discussed above. Another systematic review that looked at interventions focusing only on drug ordering found similar results, with similar caveats.

I should be clear: We have good reason to want to believe that interventions focusing on giving physicians information about the prices of the things they order should make a difference. In 2007, a systematic review demonstrated that doctors were ignorant of the costs of prescription drugs. They underestimated the prices of expensive drugs, overestimated the prices of inexpensive ones, and did not understand the extent of the difference in price between those considered cheap and those considered pricey. Another, published in 2015, explored 79 studies, 14 of which were randomized controlled trials, that suggested that physicians could be educated to deliver “high-value, cost-conscious care.”

But that education probably needs to be holistic. Flashing one point of data at a doctor does not get the job done; knowledge transmission needs to be accompanied by what this review called “reflective practice and a supportive environment.” Simply focusing on cost information may not be enough. The reasons that physicians order tests are more than financial, and efforts to influence their behavior most likely need to be more than informational.

Additionally, it may be that issues of price transparency need to involve more than one component of the health care system. While focusing solely on physicians, or on patients, might not work well, trying to work on both simultaneously might. It’s also possible that intervening solely on one procedure, test or drug at a time may not be as powerful as trying to influence spending on care over all.

Finally, trying to make physicians focus strictly on cost may be off base as well. Some care, even more expensive care, is worth it. What we really should attend to is value — the quality and impact relative to the cost. It is certainly harder to determine value than price, but that metric might make more of a difference to physicians, and to their patients.

Flexibility That A.C.A. Lent to Work Force Is Threatened by G.O.P. Plan

by Reed Abelson - NYT - June 11, 2017

In recent years, millions of middle- and working-class Americans have moved from job to job, some staying with one company for shorter stints or shifting careers midstream.

The Affordable Care Act has enabled many of those workers to get transitional coverage that provides a bridge to the next phase of their lives — a stopgap to get health insurance if they leave a job, are laid off, start a business or retire early.

If the Republican replacement plan approved by the House becomes law, changing jobs or careers could become much more difficult.

Across the nation, Americans in their 50s and early 60s, still too young to qualify for Medicare, could be hit hard by soaring insurance costs, especially people now eligible for generous subsidies through the existing federal health care law.

This news scares Fern Warnat, 59. She has gotten insurance on the federal marketplace a couple of times in the last few years. When she and her husband moved from New York to Boca Raton, Fla., she bought a policy for a few months to tide her over until she got coverage from a new job. A year later, she needed to buy insurance again when she found herself unemployed. The policy was expensive — around $800 a month.

“It wasn’t easy, but it was available,” she said.

Now she worries what would happen under the Republican plan if she left her job at a home health company that provides insurance.

“I need something to be there,” she said. “I’m going to be 60 years old. All my conditions pre-exist.”

Since the Affordable Care Act was enacted, companies have become less worried about people who want to leave but feel locked into their jobs because of health insurance, said Julie Stone, who works with corporations at Willis Towers Watson, a benefits consultant. The law “removed one of the barriers to leaving your job,” she said.

Fewer employers now offer health insurance for their retirees, she said. The other alternative is Cobra, the federal law that requires companies to allow workers to remain on their employer’s plan if they pay the full monthly premiums, which are often extremely expensive and out of reach for many people. The coverage generally lasts no more than a year and a half. Cobra was a “Band-Aid on a broken market,” Ms. Stone said.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated in an analysis last month that states covering one-sixth of the population would take waivers that allowed insurers to charge people with pre-existing conditions more. It predicted that such consumers “would be unable to purchase comprehensive coverage with premiums close to those under current law and might not be able to purchase coverage at all.”

The budget office did note that the House bill would potentially lead to lower prices, especially for younger and healthier people. In most markets, the low premiums would “attract a sufficient number of relatively healthy people to stabilize the market.”

But the budget office also warned that markets in states that allowed insurers to charge higher premiums for people with pre-existing conditions — whether high blood pressure, a one-time visit to a specialist or cancer — could become unstable. Some places are already experiencing a dearth of insurers. More companies could exit as they struggled to make money in highly uncertain conditions.

Millions of people could also wind up with little choice but to buy cheap plans that provided minimal coverage in states that opted out of requiring insurers to cover maternity care, mental health and addiction treatment or rehabilitation services, among other services required under the Affordable Care Act. Consumers who could not afford high premiums would wind up with enormous out-of-pocket medical expenses.

The individual market has always been characterized by heavy churn, and insurers struggle to meet the needs of these short-timers, particularly the young and healthy, for whom coverage can be expensive. “It’s a huge challenge, even independent of the A.C.A.,” said John Graves, a health policy expert at Vanderbilt University.

Insurers say they have had a hard time accurately estimating the medical costs of the changing pool of customers who need relatively short-term coverage and pricing their plans high enough to cover those costs. Aetna, one of the large national insurers that has decided to leave the market, said about half of its customers were new, and it blamed “high churn” as one reason the company lost money.

Older people with potentially the most expensive conditions account for almost 30 percent of those who enrolled for insurance on the exchanges this year.

David Clark wanted to retire from his job at Sam’s Club at age 62, three years before he would qualify for Medicare. He and his wife, Phyllis, who now live in Delray Beach, Fla., were not in good health. He has a heart ailment, and she has diabetes. Before passage of the Affordable Care Act, he said, he would have had to keep working.

“We wouldn’t have been able to buy insurance at any price,” he said.

But he was able to retire and get coverage on one of the marketplaces. “This has been three of the greatest years of our life,” said Mr. Clark, who spends much of his time mentoring college students. When he needed triple bypass surgery at age 64, he was covered.

Many people are keenly aware that the existing marketplaces provide a safety net, even if it is far from ideal.

Dr. Marie Valleroy was able to stop working because she could afford to buy insurance on the federal exchange for four years until she was old enough to get Medicare. She has multiple sclerosis, and her symptoms were making it harder for her to see patients in Portland, Ore. “It was time for me to retire, truthfully,” she said. Her medications cost upward of $5,000 a month.

And the law made it possible for Bobby Evans, now 35, to move to New Orleans two years ago to be with his girlfriend, now his wife. Because he was working part time until he could find a permanent position, he bought a policy through the state marketplace.

He and his wife have talked about opening their own consulting firm, but the plan is being delayed, he said, depending on what happens with the federal law providing individual insurance. “Health care is a big-time barrier for a lot of people’s professional growth,” Mr. Evans said.

Republican senators are privately crafting a health care bill, raising alarm from Democrats

The Newshour - PBS - June 12, 2017

JUDY WOODRUFF: This is an important week for the fate of a bill designed to replace and potentially overhaul the health care law often referred to as Obamacare.

Republican senators are trying to finish drafting key portions of their own bill affecting coverage and costs. But Democrats say the entire battle over repealing the law is quite different from standard operating procedure, and not nearly transparent enough.

Lisa Desjardins looks at how it’s playing out in the Senate.

LISA DESJARDINS: Right now the debate over health care is red hot in Congress, but only behind closed doors, as Republicans privately try to craft a Senate bill.

And that is something Democrats, like Senator Claire McCaskill last week, have been raising publicly.

SEN. CLAIRE MCCASKILL, D-Mo.: We have no idea what’s being proposed. There’s a group of guys in a backroom somewhere that are making these decisions. There were no hearings in the House. I mean, listen, this is hard to take, because I know we made mistakes on the Affordable Health Care Act, Mr. Secretary.

And one of the criticisms we got over and over again, that the vote was partisan. Well, you couldn’t have a more partisan exercise than what you’re engaged in right now. We’re not even going to have a hearing on a bill that impacts one-sixth of our economy.

LISA DESJARDINS: McCaskill wants something called regular order. What is that? Well, it used to be the normal process. A bill goes through committee hearings, where experts and those affected by an issue ring in.

Then senators on the committee can vote to change the bill with amendments. And then, when a bill gets to the Senate floor, regular order means another chance to change it with amendment votes there too.

In 2009, with the Affordable Care Act, two Senate committees held three months of hearings and went through weeks of voting on amendments.

More recently, Senate Leader Mitch McConnell said he wanted regular order when Republicans took over in 2015.

SEN. MITCH MCCONNELL, Majority Leader: We need to open up, open up the legislative process in a way that allows more amendments from both sides.

LISA DESJARDINS: But that’s not how Republicans so far have planned this health care debate. Again, in regular order, bills go through committees and amendment votes. Instead, this time around, Senate Republicans have indicated they may send their health care bill straight to the Senate floor with little, maybe no chance to amend it. And they have held no hearings on the bill so far.

Leading this process is Republican Senate Finance Chairman Orrin Hatch.

SEN. ORRIN HATCH, R-Utah: Well, I don’t know that there’s going to be another hearing, but we have invited you to participate.

LISA DESJARDINS: Who stressed to McCaskill that he wants Democratic ideas, if not more hearings and votes. But that differs from Hatch in 2009, when Republicans were the minority, and he thought Democrats were moving too fast on health care.

SEN. ORRIN HATCH: We at least ought to take the time to do this right.

LISA DESJARDINS: In the end, it took Democrats 14 months to pass their health care bill in 2009 and 2010. That’s why this moment is critical. The Senate will make or break health care reform. And Senate leaders, including Hatch, have said they want to pass a full health care bill by the end of this month. That’s just nine or 10 legislative days away.

For the PBS NewsHour, I’m Lisa Desjardins.

Pet Insurance Is the Latest Work Perk

by Susan Jenks - NYT - June 7, 2017

Jessica Parsons, an intensive-care nurse in Indianapolis, had given little thought to pet insurance. But when her employer, Indiana University Health, offered it as part of the company’s regular benefits package several years ago, she signed up, the $40 monthly premium coming out of her paycheck automatically.

It was fortunate timing. Shortly after getting the insurance, her then 2-year-old yellow Labrador retriever, Charlie, slipped under a tractor on her farm and suffered a crushed back and tail. Soon, the dog could no longer move her back legs and had blood in her urine. Rushed to Purdue University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Charlie underwent one operation to stabilize the spine and one to remove a badly damaged kidney. Her pet insurer, Nationwide, paid most of the $14,000 bill.

Today, Charlie is doing well. “Compared with dealing with human insurance, I found it pretty pleasant,” Ms. Parsons said of the experience.

Ms. Parsons is part of a fast-growing trend in veterinary medicine: employer-sponsored benefit plans that insure the family pooch or cat ( even the occasional ferret or potbellied pig) against accidents and illness. Some 5,000 companies, including Microsoft, Yahoo, Xerox and Hewlett-Packard, now offer pet insurance, sometimes covering part or all of the costs, in an effort to lure talent but also to recognize the strong emotional bonds between people and pets.

It’s a side of the insurance industry that is growing rapidly, said Dr. Carol McConnell, chief veterinary medical officer for Nationwide, the nation’s largest pet insurer. “People find this type of insurance more credible if an employer has vetted it first.”

As the sophistication of veterinary medicine grows, so do pet owners’ concerns about whether they can afford to pay for care. The American Pet Products Association, a trade group, estimates that Americans will spend nearly $70 billion on their pets this year, with nearly a quarter of that devoted to veterinary care.

Pets undergo state-of-the art imaging tests like CT and M.R.I. scans to diagnose problems, and they get valve replacements for ailing hearts, chemotherapy to fight many cancers, surgery to extract impacted teeth, even transplants for failing kidneys.

“Pet insurance is a game-changer for many pet owners” who otherwise could never afford these procedures, said Dr. Tracey Jensen, a private-practice veterinarian in Wellington, Colo., and a former president of the American Animal Hospital Association, which accredits animal hospitals in the United States and Canada.

“Pets today occupy a special place in people’s lives,” Dr. Jensen said. “They’re family members, and their owners don’t want to cut corners on care.”

Only a small fraction of pet owners in the United States carry pet insurance. An estimated 1 to 2 percent of the nation’s nearly 90 million pet dogs and more than 94 million pet cats are insured, industry statistics show.

Nevertheless, the marketplace has grown from one pet insurer, Veterinary Pet Insurance (now called Nationwide), in 1982 to at least 11 companies today, including the Hartville Pet Insurance Group (now called Crum & Forster), which offers insurance through the A.S.P.C.A. The North American Pet Health Insurance Association cited a growth rate of 12 to 15 percent in policy holders over each of the last two years.

“There’s definitely an uptick in the number of insured pets out there,” said Chris Middleton, president of Pets Best, an insurer in Boise, Idaho. He said that since 2013, the 11-year-old company has seen a 60 percent increase in the number of employers seeking pet insurance for their workers. But unless owners have faced high vet bills in the past (as Mr. Middleton has with his “rock-eating hound,” he said), many are deterred by the monthly premiums.

Much like human health insurance, pet insurance comes with a dizzying array of options. A basic plan for certain illnesses and accidents can cost $20 or less a month; more comprehensive policies covering annual wellness exams, vaccinations, blood work and a range of treatments start at around $63 a month.

In general, cats tend to cost less to insure than dogs. Many pet insurance companies charge more for breeds prone to certain medical conditions, like cancers or heart disease; a large dog, like a Great Dane, will cost more to insure than a Chihuahua.

“My best advice is find others who have the insurance you’re interested in, talk to your vet or ask for referrals from the company,” said Heidi Ganahl, founder of Camp Bow Wow, a dog-boarding and -training franchise. She said that before she sold the company in 2014, she offered her 40 employees pet insurance and always insured her own pets. “The biggest thing you want in any policy is the catastrophic stuff,” she said.

“By and large, most pet insurance is primarily there for injury and disease,” not for wellness, said Dr. Christopher Gray, the director of Michigan State University’s Veterinary Medical Center in East Lansing. He does not insure his two dogs and two cats. His recommendation: Look at deductibles, co-payments and whether a policy covers a pet throughout its lifetime or ends when it hits a certain age.

Dennis Rushovich, senior vice president of the Hartville Group, suggests asking whether a plan covers exam fees as well as any medications or specialized foods a vet may prescribe, and whether the plan has an annual cap on what it will pay.

Consumers Advocate, a company that rates a range of products, began sifting through the variables several years ago to rank pet insurers according to customer reviews, upfront deductions and whether they pay for a disease’s continuing costs.

“If your dog has hip dysplasia, it can get quite expensive” if an insurer caps the costs, said Sam Niccolls, the company’s founder. Some insurers, he said, pay for spaying or neutering along with other relatively inexpensive wellness tests but not the real drivers of veterinary cost: emergencies or chronic diseases.

Some critics question the rankings’ reliability. Consumers Advocate makes its money, in part, from partnerships with some of the same insurers it evaluates, though the company says it makes its assessments independently. Others say that rankings may not be up to date (since insurers are continually updating offerings) or may be skewed by bogus consumer reviews, a widespread problem throughout the internet.

In a 2016 cost analysis, Consumer Reports looked at coverage from four industry competitors for two pets: a 12-year-old Lab mix with skin cancer named Guinness and a mixed-breed cat named Freddie. It found that for serious diseases, like cancer, all the policies carried a definite financial benefit. But for less dire conditions (an expensive dental cleaning for Freddie), only one company paid more than the annual premiums’ cost.

Consumer Reports acknowledged that the limited sample size of the study and the inability to predict the future medical needs of a pet made blanket recommendations difficult. But, it concluded, “if you’d like help with unexpected, large vet bills, a plan may be worth considering.”

During her veterinary training at Colorado State University, Dr. Christine Hardy remembers, she struggled to pay nearly $5,000 in bills after her golden retriever, Sam, developed elbow problems and tore a cruciate ligament in his knee. “He was a bit of an orthopedic disaster,” said Dr. Hardy, now the director of operations at the university’s Flint Animal Cancer Center.

Sam has since died, but the experience persuaded her to insure her next pet, Winston. The policy covered 80 percent of the nearly $9,000 to treat the 8-year-old dog’s hemangiosarcoma, a blood vessel cancer in an unusual location: the roof of his mouth. “Because we had insurance, I never felt like finances weighed in our decisions,” Dr. Hardy said. “Instead, we were able to make choices based on what we thought best for Winston.”

“I think of pet insurance in the same way as I do car insurance,” she added. “It’s there when things go terribly wrong.”

If your employer offers a plan, she said, at least take a look.

It’s time to make it legal for Americans to order prescription drugs from abroad

by Ed Silverman - STAT - June 12, 2017

Every day, countless people across America order prescription drugs from pharmacies in other countries as they hunt for something increasingly elusive — affordable medications.

But there’s a problem. Under most circumstances, importing medicines is illegal.

And it is time to scrap this prohibition, unless Congress finds another way to drive down drug costs.

Consider this: Sixty percent of Americans say lower drug costs should be a top priority, and a whopping 72 percent support the idea of importing medicines from Canada, according to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll. In fact, 8 percent of adults surveyed reported that they or someone in their household have already bought prescription drugs from outside the U.S.

Meanwhile, the cost of 20 widely used drugs is three times cheaper in Canadian than in New York pharmacies, according to PharmacyChecker.com, a website that vets overseas pharmacies and compares prices. And as drug makers regularly hike prices — sometimes to sky-high levels — or set steep price tags for the newest treatments, more American pocketbooks are pinched than ever before.

“The problem is getting worse,” said Rep. Peter Welch, a Vermont Democrat who last week unsuccessfully attempted to stick an importation amendment onto a regulatory bill.

Yet from the time nearly two decades ago when seniors made headlines by taking buses to Canada to stock up, the pharmaceutical industry has stymied every attempt to allow Americans to import medicines. Drug makers have succeeded by exploiting fears over safety concerns. They’ve also lavished political contributions on members of Congress.

The latest example of pharma pushing back against importation came in the form of a report released this month by former FBI director Louis Freeh, who was once a Bristol-Myers Squibb board member and now runs a consulting firm. His sobering conclusion: Importation would increase the threat of counterfeit medicines into the U.S.

“The burden of enforcement will fall on American authorities and the resources for this are really minimal,” said Freeh, whose firm was commissioned by the Partnership for Safe Medicines, a nonprofit with ties to the pharmaceutical industry. “… I think safety would go right off the boards.”

His prediction comes shortly after four former Food and Drug Administration commissioners chimed in with their own dire warnings. In an open letter to Congress, they wrote that importation is “a complex and risky” idea that would harm consumers and compromise the existing safety system.

To be sure, there is reason to be cautious.

Counterfeit medicines have entered the U.S. supply chain before. In one widely publicized episode several years ago, a Canadian company supplied doctors with fake copies of the Avastin breast cancer treatment. And in 2003, a crime ring successfully peddled phony Lipitor pills to wholesalers, some of whom looked the other way.

But this doesn’t mean that importation is impossible.

“We should be able to address the safety issue,” said Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who has studied the topic. “To not have the conversation and instead say there’s no way to import medicines safely is a cop-out.”

Many people may not realize this, but the U.S. already imports 80 percent of all active pharmaceutical ingredients used to produce medicines — and also imports 40 percent of prescription drugs, according to the FDA. And anyone who tracks FDA inspections knows that many overseas suppliers have racked up egregious safety violations.

To move the ball forward, Welch attempted to address concerns that the supply chain would be too porous, potentially allowing in phony drugs. He also borrowed elements from a bill introduced by Sen. Bernie Sanders that would create steps to allow both individuals and wholesalers to import drugs. The Sanders bill would also prevent drug makers from restricting supplies to Canada or charging higher prices to Canadian pharmacies to make ordering from that country less desirable.

There may be legitimate questions, though, such as whether Canadian pharmacies could fill prescriptions for U.S. citizens. And there are concerns the Canadian government might step in to curb sales over worries about shortages. Moreover, the bill would rely heavily on Canadian regulators to ensure safety.

“This would be quite a departure for the FDA,” observed Tim Squire of the Fasken Martineau law firm in Toronto.

Consequently, the bill has gone nowhere fast.

But doing nothing to curb drug prices is not an option. Unfortunately, Congress is good at doing nothing. Meanwhile, Americans will buy drugs from overseas, and so lawmakers need to take this seriously.

After all, you don’t need to take a bus anymore to buy lower-cost medicines from north of the border.

Letter to the editor: Remove the profit motive and health care for all will work

Letter to the Editor - Porland Press Herald - June 13, 2017

The latest news is that Senate Republicans are going to pass a new health care bill without any hearings. Sen. Susan Collins has been silent on this fast-tracking, although she and Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., have proposed their own replacement for the Affordable Care Act.

Why isn’t she out front on this? The answer may lie in the fact that her plan is flawed and does nothing to solve the fundamental problem with our expensive health care system: the profit motive.

Every other wealthy nation has come to the conclusion that profit cannot be a motive when delivering health care. There was a time when major insurance companies like Blue Cross-Blue Shield were nonprofits, so this should not be a foreign concept for Americans. What is needed is a plan that eliminates profit and covers everyone, regardless of income.

Of course, this requires us to agree that health care for all is a right. We are the only wealthy nation that struggles with this moral question. Why?

Ask older Americans if they like Medicare or ask vets if they like the Veterans Affairs system and the majority say “Keep your hands off my health care.” The Cassidy-Collins bill fails to consider any of the good features of either system and instead relies on the profit motive for delivering health care. Simply put: You make profits only when you insure healthy people, make coverage very expensive for sick people and allow millions to go without any health care.

If we, the public, answer that moral question in the affirmative, we then need to demand that politicians craft a plan that contains the best features of Medicare and the VA system. Simple, but maybe impossible in our polarized nation. Sad.

Tom Mikulka

Healthcare Committee, Elders for Future Generations

Cape Elizabeth

Report: More Kids Going Without Health Coverage in Maine

by David Sharp - Associated Press - June 13, 207

PORTLAND, Maine - A new report says the percentage of Maine children without health care coverage grew 50 percent in Maine during a five-year period that coincided with tightened Medicaid eligibility guidelines and the governor's decision not to expand Medicaid.

Neither of those actions by the LePage administration affected coverage for children, but child welfare advocates believe children nonetheless went off the Medicaid rolls when their parents lost coverage.

The report by the Annie E. Casey Foundation on Tuesday indicates Maine and North Dakota were the only states to see increasing numbers of children without insurance from 2010 to 2015. The report contends 14,000 Maine children were without coverage.

The governor's office contends it's the parents' responsibility, not the state's, to ensure children are receiving health care for which they're eligible.

Neither of those actions by the LePage administration affected coverage for children, but child welfare advocates believe children nonetheless went off the Medicaid rolls when their parents lost coverage.

The report by the Annie E. Casey Foundation on Tuesday indicates Maine and North Dakota were the only states to see increasing numbers of children without insurance from 2010 to 2015. The report contends 14,000 Maine children were without coverage.

The governor's office contends it's the parents' responsibility, not the state's, to ensure children are receiving health care for which they're eligible.

Editor's Note:

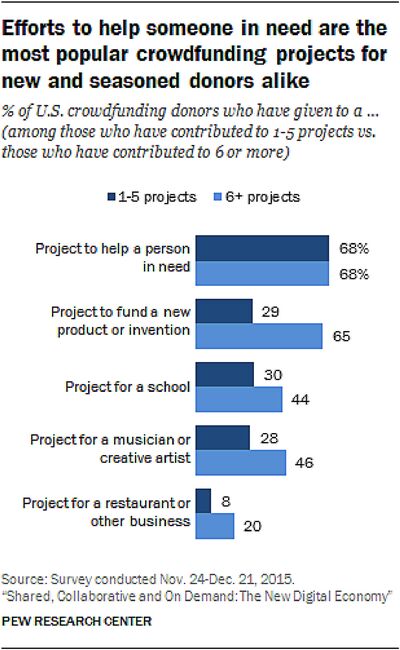

Does anybody besides me see anything terribly wrong with the crowdfunding approach to medical debt, described in the following clipping?

Wow.

- SPC

America’s Health-Care Crisis Is a Gold Mine for Crowdfunding

by Joanne Wolley - Bloomberg - June 12, 2017

Crowdfunding platforms such as GoFundMe and YouCaring have turned sympathy for Americans drowning in medical expenses into a cottage industry. Now Republican efforts in Congress to repeal and replace Obamacare could swell the ranks of the uninsured and spur the business of helping people raise donations online to pay for health care.

But medical crowdfunding doesn't have to wait for Congress to act. Business is already booming, and its leaders expect the rapid growth to continue no matter what happens on the Hill.

"Whether it's Obamacare or Trumpcare, the weight of health-care costs on consumers will only increase," said Dan Saper, chief executive officer of YouCaring. "It will drive more people to try and figure out how to pay health-care needs, and crowdfunding is in its early days as a way to help those people."

At industry leader GoFundMe, medical is one of the biggest fundraising categories. CEO Rob Solomon has said it's what "helped define and put GoFundMe on the map” and has called the company, founded in 2010, "a digital safety net."

That net grew wider this year with GoFundMe's acquisition of CrowdRise, which was co-founded by the actor Edward Norton. It adds to the company's business helping people fundraise for charities and sends those who need funds for "medical bills, a friend’s tuition, a group volunteer trip, or any personal cause" to GoFundMe.

Growth has been rapid. In a September 2015 LinkedIn post, Solomon wrote that the one million campaigns set up over the previous year had raised $1 billion from nearly 12 million donors. By February 2016, the total was $2 billion. In October 2016, it was $3 billion, from 25 million donors. A NerdWallet study of medical crowdfunding said GoFundMe had indicated that $930 million of the $2 billion raised in the period the study analyzed was from medical campaigns.

YouCaring, meanwhile, acquired GiveForward this year; medical fundraisers made up 70 percent of GiveForward's campaigns. The combined companies have 8 million donors who have contributed $800 million to a wide range of campaigns. A big part of that total was donated to medical campaigns, according to the company. It was approaching 50 percent of all fundraisers at YouCaring before the acquisition, and the growth rate is set to triple this year, Saper said.

With enough volume, the business of helping people raise money for medical care has a lot of profit potential. GoFundMe takes 5 percent of each donation, 2.9 percent goes to payment processing, and there's a 30¢ transaction fee. Smaller sites, such as Fundly and FundRazr, charge much the same. YouCaring donors pay just a 2.9 percent processing fee plus the 30¢.

"We rely on voluntary contributions from donors [to run the business], so our big thrust now is how do we get the word out about it," said Saper. The company is scaling up its team and operations and hired the former global head of engagement and growth of EventBrite, Maly Ly, as its chief marketing officer in March.

Indiegogo, which started out funding filmmakers, created a separate platform in 2015 called Generosity. Medical is a top category, and users pay a 3 percent payment processing fee and the 30¢. Now Facebook has jumped into the fray. On May 24, it began allowing users to launch fundraisers for personal causes or nonprofits on their pages. Medical is one of eight available categories. For personal cause campaigns, Facebook takes 6.9 percent of each donation plus 30¢.

For more and more Americans, vying in a popularity contest for a limited supply of funds and sympathy may be the only way to pay the doctors and stay afloat. House Republicans passed a bill last month to replace the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare. As is, the Congressional Budget Office estimates, it would leave 23 million more Americans uninsured in 2026 than under the ACA. Even a law just resembling the bill is likely to raise the cost of health care for older and sicker Americans and for those with preexisting conditions, bolstering the medical crowdfunding business.

The industry still represents just a fraction of the hundreds of billions of dollars Americans pay annually out of pocket for health care, said Saper. Medical crowdfunding is "highly, highly scalable and has a ton of runway," he said. "The growth rate of the industry is showing that this can absolutely be an impactful safety net for a lot of individuals and communities to help each other."

The remarkably named Producing a Worthy Illness: Personal Crowdfunding Amidst Financial Crisis, a study published this year by the University of Washington/Bothell, offers a striking perspective on some of those communities. Personal medical campaigns on GoFundMe were likelier to come from people living in states that chose not to expand Medicaid under the ACA, preliminary results of the study showed. Fifty-four percent of 200 randomly sampled campaigns last year came from those states, though they are home to just 39 percent of the U.S. population. Trumpcare would sharply curtail Obamacare's expansion of Medicaid.

"We had a huge number of campaigns from Texas, which is often recognized as the state where it's most difficult to qualify for Medicaid and other public insurance," Professor Nora Kenworthy, co-author of the study, said. "A lot of the campaigns are really using GoFundMe as a safety net," asking for "help with lost wages, help getting basic health-care services and support."

Most medical crowdfunding campaigns are a far cry from Taylor Swift's $50,000 gift on GoFundMe to a young girl with aggressive leukemia, or $1 million in donations for a mother whose cancer returned when she was pregnant with quadruplets. "Often, funds people are raising are for a huge range of costs that go along with care, like travel to the place where you will get care, because insurance doesn't really cover that," said Indiegogo's senior director of social innovation, Breanna DiGiammarino. In the future, more fundraisers will likely seek to cover premiums and deductibles rather than the cost of care itself, she said.

"Crowdfunding is being treated a little like crowd-insurance now," said Daryl Hatton, CEO of Canada-based crowdfunding platform FundRazr.

Yet crowdfunding's business model is a poor fit for the gargantuan, mundane, never-ending health-care costs of many online campaigners. Some get just 10 to 20 percent of what they ask for, said Jeremy Snyder, a health sciences professor at Simon Fraser University in Canada, where the need remains even with a national health-care system. Snyder's research, which includes analysis of ethical issues raised by medical crowdfunding, has focused on people seeking funding for cancer treatments on Canadian crowdfunding sites.

And, of course, in the U.S. as in Canada, some campaigners get less than that, or nothing at all. Slightly more than one in 10 health-related online campaigns reached their goal in the NerdWallet report. The Bothell study found that 90 percent of the 200 GoFundMe campaigns didn't reach their goal, and that, on average, fundraisers got 40 percent of what they asked for. That doesn't sound like much of a fix to Snyder.

"Is this something that is going to be a solution to a lack of health insurance?" he said. "Absolutely not."

One reason for the discouraging statistics is that while most of the campaigns are ordinary—and no less urgent for it—it is often the extraordinary ones that do best.

“The more dramatic the need, the more successful" the fundraiser, said Adrienne Gonzalez, who follows the industry as the creator of GoFraudMe.com, a site that exposes fraudulent campaigns on GoFundMe.

Among the "most active" campaigns featured on generosity.com on May 30 were one to help pay for treatments for a man diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia and one for a woman struggling to cover "co-pays, travel expenses, food, lodging, essentials" as she tends to her 19-year-old daughter, who is scheduled for a kidney transplant. A third solicited funds for a woman without insurance who had been struck by lightning.

Those appeals are very different from that of an ice hockey player who had broken her collarbone in a game and started a campaign on generosity.com. She asked for $1,500 to help cover her $1,000 deductible and other costs, including being sidelined from her landscaping job for at least six weeks. Over a month, she raised $252 from seven people, or 17 percent of her goal. It was something.

“ ‘I need help with my deductible’—they are not going to be very successful,” said Gonzalez, who believes crowdfunding has done a lot of good but presents "this whole socioeconomic problem" because "you almost have to be a marketing guru" to create a successful campaign.

The Bothell researchers noticed a bias among donors toward funding solvable problems. "Injections that cost $10,000 every six months are a more solvable problem than a campaign for a family citing a litany of challenges, like utility bills that aren't being paid because the family is paying for health care," said Professor Lauren Berliner, Kenworthy's co-author on the study. Media and digital savvy play a big part in attracting donations. The campaigns with hashtags, images, and flashy elements got the most financial support, the study found.

"Most campaigns are paid for by friends, and friends of friends," said Hatton of FundRazr. "A lot of it has to do with the strength of your social network," as people you helped now dip into a "karma bank" and help you. People with fewer financial resources may not have been able to build up that goodwill and may not have that wide and deep a social network to call on, he said.

Then there was the woman in her 30s who walked into a free clinic where Dr. Edward Weisbart, who chairs the Missouri chapter of Physicians for a National Health Program, volunteers. She was with her mother, appeared unable to speak, and had a "peculiar affect, like a crazed wild animal," he said. It turned out she had lived for years with seizures every two to three days until she found a medication that had cut the frequency to once every two months. When she visited Weisbart, she had lost her insurance and had 10 days of medication left.

"Her inarticulate state was not a consequence of the seizures," Weisbart said. "It was terror over what her life would be like if she couldn't get the medication." Once he explained that the clinic could mail her the drug and that it would cost $40 instead of $1,500, "she transformed into this normal, lucid, almost friendly person," he said. "But she could never have used crowdfunding, because she was literally beside herself."

Hatton is seeing more "fatigue" around crowdfunding efforts. Weisbart observed that "when you get your first request, you probably give a high amount. But as you get besieged and realize how common these requests are, donations will go down. We can't keep on giving to everyone who asks."

One site keeping its distance is Kickstarter, where donors fund creative projects.

"If we had personal health-care campaigns, it could create a strange moral equivalency," said Justin Kazmark, the company's vice president of communications. "If you see documentary filmmakers trying to get $10,000 for a film alongside a project for someone whose dog needs dental surgery, or for disaster relief, it changes the mindset and frames the whole thing differently."

No comments:

Post a Comment