U.S. government spent more on health care in 2022 than six countries with universal health care combined

By Annalisa Merelli - STAT - December 19, 2023

American taxpayers footed the bill for at least $1.8 trillion in federal and state health care expenditures in 2022 — about 41% of the nearly $4.5 trillion in both public and private health care spending the U.S. recorded last year, according to the annual report released last week by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

On top of that $1.8 trillion, third-party programs, which are often government-funded, and public health programs accounted for another $600 billion in spending.

This means the U.S. government spent more on health care last year than the governments of Germany, the U.K., Italy, Spain, Austria, and France combined spent to provide universal health care coverage to the whole of their population (335 million in total), which is comparable in size to the U.S. population of 331 million.

Between direct public spending and compulsory, tax-driven insurance programs, Germany spent about $380 billion in health care in 2022; France spent around $300 billion, and so did the U.K.; Italy, $147 billion; Spain, $105 billion; and Austria, $43 billion. The total, $1.2 trillion, is about two-thirds of what the U.S. government spent without offering all of its citizens the option of forgoing private insurance.

This isn’t an aberration. The fact that, for many years, more taxpayer dollars have gone to health care in the U.S. than in countries where the health system is actually meant to be taxpayer-funded is central to the argument made by economists Amy Finkelstein and Liran Einav in their recent book, “We’ve Got You Covered: Rebooting American Health Care.”

“We’re already paying as taxpayers for universal basic automatic coverage, we’re just not getting it,” Finkelstein said at the STAT Summit this past October. “We might as well formalize and fund that commitment upfront.” The numbers in this CMS report illustrate their point: The U.S. would not need to raise taxes in order to provide basic universal coverage, since it’s already responsible for picking up a relative majority of the expenses.

Offering universal coverage would cut health care costs for individuals too, according to Finkelstein and Einav. That’s because people would have the choice not to purchase additional private health insurance, thereby avoiding contributions that get deducted from their paychecks as well as out-of-pocket charges. According to the latest CMS data, Americans spent $471 billion on out-of-pocket health expenses in 2022, on top of whatever they were already paying for health care coverage.

Overall, health care spending grew 4% in 2022 from the previous year, accounting for 17.3% of gross domestic product. The increase was largely driven by growth in Medicaid and private health insurance spending.

National advocacy group blames hospital consolidation for Maine’s high health care costs

A national health advocacy group is blaming hospital consolidation in Maine for spurring higher prices at hospitals for patients with private insurance.

But Maine hospital officials say consolidation is not the force driving the prices, and that the explanation lies with the state’s older population and low Medicare reimbursement rates that shift the costs of health care to younger people with private insurance.

Maine’s two biggest hospital systems – MaineHealth and Northern Light Health – have both grown larger over the last 20 years, with formerly independent hospitals joining their networks.

Mid-Coast Hospital in Brunswick and the former Goodall Hospital in Sanford are among the more recent additions to the MaineHealth system, which includes Maine Medical Center in Portland. Mercy Hospital in Portland and Mayo Regional Hospital in Dover-Foxcroft are among the hospitals that in recent years joined Northern Light Health, which includes Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor.

While independent hospitals and other networks remain – including Central Maine Healthcare in Lewiston and MaineGeneral Medical Center in Augusta – MaineHealth and Northern Light dominate the state’s health care market.

“What causes prices to rise uncontrollably, leaving patients subject to thousands of dollars in medical bills? Look no further than consolidation, where dominant hospital systems control markets and set prices as high as they’d like,” said Darbin Wofford, health policy adviser for Third Way, a center-left think tank based in Washington, D.C. Health care reforms are among the topics that Third Way advocates for, including clean energy, reforming gun laws and abortion access, among many other issues.

Third Way is releasing a case study analysis of Maine’s hospital costs on Thursday and provided the Press Herald with an early look at the findings.

In an interview, Wofford said consolidation in states such as Maine tips the scales heavily in favor of hospital networks when negotiating contracts with insurance companies. Those contracts influence the health insurance premiums, deductibles and other costs that people pay.

“Insurance companies can’t say to hospitals, ‘No, we don’t want to take your prices,’ ” Wofford said.

According to the Health Care Cost Institute, the Portland market was the 21st “most concentrated” health care market of 183 markets measured, which means Portland has less hospital choice for patients than much of the country. The Portland market was the only market measured in Maine.

Wofford pointed to hospital prices for private insurers, which are on average 275% of the prices Medicare pays for services, or nearly three times as high. Maine’s average costs are the highest in New England, and far above the national average of 224% of Medicare, it found. Maine’s average costs rank 19th among states. South Carolina is the state with the highest hospital prices for private insurers, at 322% of Medicare prices.

But Dr. Andy Mueller, CEO of MaineHealth, said the explanation for private insurance prices at hospitals has far more to do with Maine’s demographics.

When a higher percentage of the hospital patient mix is insured by Medicare – generally patients 65 and older – that skews hospital prices. Because Medicare’s reimbursements are so low and do not cover hospitals’ actual costs, the difference has to be made up by private insurers, Mueller said.

That’s true of any hospital in the country. But, he said, “we’re the oldest state in the nation.”

OLDEST STATE IN THE NATION

According to the U.S. Census, Maine’s median age is 44.8 years, the oldest in the nation. “That puts a greater burden on those who have commercial insurance to make up the difference,” Mueller said.

Terri Canaan, chief marketing and communications officer for MaineHealth, pointed to an analysis that showed Maine’s Medicare spending per enrollee – which includes hospital and non-hospital spending – is below the national average. The national average is $11,080, while Maine’s spending is $9,159 per enrollee, according to KFF, a national health policy think tank.

Health care costs are influenced by a number of factors, such as the push and pull of health care network contract negotiations with insurers, the health and demographics of the population served, federal and state regulations, and competition among health care providers, among other things.

A Forbes Advisor analysis in 2022 combined 11 key health care cost metrics to try to determine the difference in health care costs by state. By that measurement, Maine has the seventh-highest health care costs in the nation, at $11,505 per person. South Dakota was the most costly in the nation, with $11,736 per capita, while Michigan had the lowest health care costs at $9,524. The analysis includes all health care costs, not just the costs incurred at hospitals or costs paid with private insurance.

Denise McDonough, president of Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield in Maine, said hospital consolidation is one of the factors driving up costs in Maine.

“We have seen significant hospital consolidation in Maine over the years, which has reduced competition, increased costs, and limited access to care – leaving Mainers with less choice,” McDonough said.

Anthem and MaineHealth became embroiled in a public contract dispute in 2022, with Maine Medical Center nearly withdrawing from Anthem’s network in 2023 before an agreement was reached in August 2022. The dispute became public with both sides providing the media with examples of hospital overcharging of patients, and of the insurance company denying needed care.

Both Anthem and MaineHealth officials have claimed that the other side has too much leverage in negotiations.

Mueller, on Wednesday, countered the argument made by Third Way that Maine’s hospitals have leverage over insurers.

“We’re still a ‘mom and pop’ industry in comparison to the consolidation that has happened on the health insurance side,” Mueller said. “These are massive companies, and we are not, relative to (insurers). We are a tiny speck on the wall compared to them.”

REFORMS PROPOSED

Third Way has proposed a number of reforms, including tougher price transparency laws, and laws that they say would help insurers when negotiating with hospital systems.

Maine is debating regulation of facility fees, which can reach hundreds of dollars for patients for just walking into a hospital for care and are often hidden in medical bills and passed onto the patients. After a Press Herald report in 2022 that featured patients complaining about facility fees, the Maine Legislature passed a bill that created a task force, which is studying possible changes to state law.

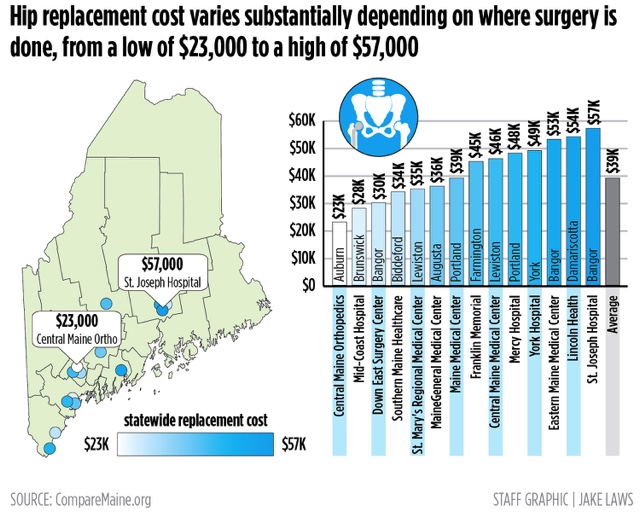

The federal government requires hospitals to disclose prices, but some say the law doesn’t go far enough and lacks an enforcement mechanism. Maine has the CompareMaine.org website, which allows for comparison pricing of some procedures, such as colonoscopies, blood tests and hip replacements.

McDonough, the Anthem president, agrees that more needs to be done, and calls Third Way’s suggestions a “good first step.”

But Mueller, the MaineHealth CEO, said that one of the bills currently under consideration by the Maine Legislature would protect insurers’ ability to reduce costs, such as by giving financial incentives to patients to go to less expensive clinics. MaineHealth does not prevent such cost-saving efforts, he said.

But Mueller said also built into the bill – L.D. 1708 – is a provision that would prevent hospital networks from terminating contracts with insurers.

“The only leverage we have is to terminate a contract,” Mueller said. “We believe we ought to have the ability to terminate an agreement the other party is not living up to.”

McDonough said, “we hope we can continue the conversation about greater transparency and advance legislation to protect members’ access to affordable care.”

Opinion: Physicians like me know our health care system must change

A recent experience as a patient served as a good example of how dysfunctional things can get.

by Scott Schiff-Slater - Portland Press Herald - January 4, 2023

I am a physician with a small family practice in Central Maine, and I love my job.

Our health care system in the U.S. is amazing, and yet it is also dysfunctional, expensive, inefficient and needs to be changed. Let me offer an illustration.

About a month ago at a Maine hospital I had a new type of scan done that can spare people like me from invasive cardiology procedures. That is the great part.

The bad part is that although I have excellent health insurance, and the procedure was fully approved, my out-of-pocket expense was $1,029.84 – well above my $180 co-payment. The reason, I learned, is that I was given one dose of nitroglycerin – we all know what nitroglycerin is, people with angina keep it in their pockets – but this was part of the protocol for the test as it is used to dilate the coronary arteries. If nitroglycerin is purchased at a pharmacy, insurance will cover it. If you don’t have insurance at all, it might be a few dollars. The hospital charge, my out-of-pocket expense for this one dose of nitroglycerin, was $849.84.

I was taken aback, as a consumer and as a physician. After a number of hours of research and many phone calls, I learned that it was considered a “self-administered” medication, so not covered by insurance while in the hospital. The reasons for the charge of $849.84 has to do with our health care system and how it functions, or doesn’t. I want to emphasize that the hospital was just doing what all hospitals in the United States do as they struggle to make ends meet in our current system.

I am hoping to reverse this charge. I’m working with hospital and insurance company employees, all of whom are getting paid for their time, while I do this on my own time. I am a physician who knows the system and can make the appeal. For many Maine families, pursuing the appeal would be challenging and the charge could break the family budget. This is just one example of a problem in our health care system and I know that many readers have similar tales – I hear about them daily from my patients.

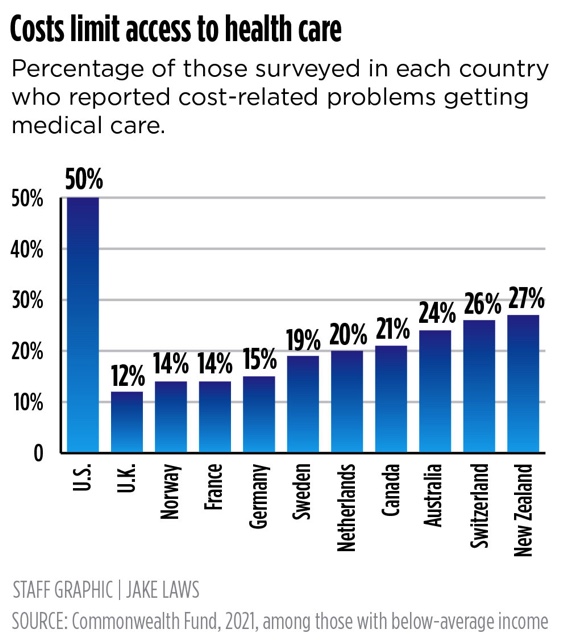

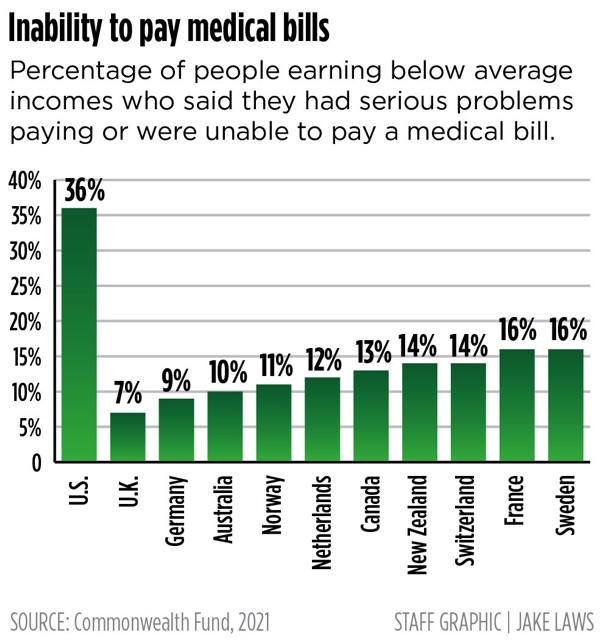

We have some of the best care and yet some of the worst. The United States is by far the most expensive health care system in the world and yet we have health outcomes for this investment that are embarrassing.

As a society, we must respond.

The Maine Medical Association is a professional organization of more than 4,000 Maine physicians, residents and medical students and almost all our members believe that our current health care system does not meet our needs and requires comprehensive change. We do not all agree on how to fix the system, just that it needs to be fixed.

The association has issued a revised statement on reform of the U.S. health care system that reviews the problems we face and offers some principles for change. It is not perfect, but I promise it will make you think. I encourage you to read the statement on the MMA website: www.mainemed.com.

Maine physicians, MMA members and members of other physician organizations urge change. Change can’t happen without more understanding from everyone of the problems, and the potential solutions, and then we’ll need help from our elected officials.

In the meantime, my heart test was OK. I will keep working on fixing that $849.84 charge.

Hidden charges, denied claims: Medical bills leave patients confused, frustrated, helpless

by Joe Lawlor - Portland Press Herald - January 12, 2023

Bill Bartlett received an $813 bill for a routine cardiac stress test that he had been told would cost him $45. Sean Dundon was charged $800 for having his sliced thumb examined and bandaged.

Both patients faced unexpectedly huge expenses for simple medical care because so-called “facility fees” were tacked onto their bills. The fees are just one example of the arcane and complex world of medical billing that so often frustrates and confuses patients.

Patients receive bills bloated by health care providers that overcharge for services and insurance companies that deny claims without explanation. And with little clout to fight back or even negotiate, feeling helpless, they often give up and pay, worn down by a system that is as time-consuming as it is obtuse.

A public, high-stakes battle between Maine’s largest hospital and its dominant insurance carrier has opened a window into the opaque world of medical billing and insurance claims, and it underscores just how powerless consumers are.

The dispute was settled last week, but the disagreement was over money. Maine Medical Center in Portland said Anthem owes it millions of dollars in overdue and unpaid claims, while Anthem contended that Maine Med has overcharged the insurer by millions of dollars. If the standoff had not been resolved, Maine Med would have left Anthem’s provider network in January, upending Maine’s entire health insurance market.

The Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram spent more than three months investigating the byzantine system of medical billing in Maine. The newspaper spoke with dozens of patients who have had billing problems, reviewed their invoices and explanations of benefits, interviewed health care executives and consulted experts in the field. The reporting reveals systemic shortcomings that are not limited to any one medical provider or insurer but are pervasive across the landscape. The Press Herald found that:

• Medical bills are confusing and opaque, and sometimes carry arbitrary and hidden costs, including a common surcharge that hospitals call a “facility fee,” charging hundreds of dollars simply for getting treatment in a hospital.

• Insurance companies deny some claims for reasons that aren’t clear and may never be explained, forcing patients to choose between waging drawn-out fights or paying hefty bills.

• Costs for procedures and insurance coverage vary so widely that even patients who carefully compare prices beforehand can wind up with bills far larger than expected.

• Even though Americans’ access to insurance expanded through the Affordable Care Act, many are still underinsured and subject to massive medical bills they don’t expect and may not be able to pay.

The practice of assessing facility fees – sometimes hiding such fees in other charges – increasingly contributes to some patients’ surprisingly large bills.

It has long been standard practice for hospitals to shift uncompensated costs, such as care for uninsured patients who can’t afford to pay their bills, to patients with insurance.

But with more patients on high-deductible plans – and insurers sometimes refusing to pay or paying only a fraction of their bills – individuals are picking up more of the tab and bearing more of the financial burden.

“The system is broken and is really in need of a major overhaul,” said Dr. Julie Keller Pease, a founding member of Maine AllCare, which advocates for single-payer systems like those in Canada and the United Kingdom.

Still, any efforts to reform or overhaul the system, especially in one small state like Maine, face huge barriers.

HIDDEN FEES

Maine patients are paying hundreds of dollars extra for routine medical tests or procedures simply because the tests are occurring at hospitals. And they may have no idea, because the “facility fees” are not clearly explained and sometimes hidden on their bills.

Bill Bartlett of Kennebunkport said he called his insurance company to check on the price before getting his routine cardiac stress test last November. A few weeks later, the 60-year-old got a bill from York Hospital for the $45 he expected plus $813 for a “facility fee.”

Bartlett only discovered the facility fee because he demanded an explanation. And before he spent months complaining and appealing, his insurance company tried to deny coverage and stick him with the bill.

“This shouldn’t be my problem,” said Bartlett, who appealed the denial. “I did due diligence to determine the cost ahead of time.”

After Bartlett refused for months to pay the bill, Harvard Pilgrim finally paid most of it a few weeks ago, without explanation.

Jean Kolak, a spokeswoman for York Hospital, said that “when a patient receives services at York Hospital, their invoice will include a facility fee.”

“The amount of this fee is created, based on a variety of factors, such as the cost of staff, equipment, technology, medications utilized, supplies and in some clinical care areas, the acuity of the patient,” Kolak said in a statement.

Ann Woloson, executive director of Consumers for Affordable Health Care, a Maine-based advocacy group, said the organization is receiving increasing numbers of complaints about facility fees and may seek legislation to limit when they can be charged and require that patients be warned ahead of time.

“If facility fees are charged, the brunt of those fees should not be on the consumer,” Woloson said.

Al Swallow, chief financial officer for MaineHealth, the hospital network that includes Maine Medical Center and seven other Maine hospitals, said facility fees are an industry standard. They reflect the need for hospitals to cover higher expenses than other medical providers incur, he said.

“Hospital settings have more costs than (outpatient) settings, including the fact that many of the services delivered by hospitals go uncompensated, either because of charitable care or the fact that Medicare and Medicaid do not cover the full cost of care delivered in a hospital,” Swallow said in an email response to questions. “Hospital settings are also more highly regulated, and meeting those standards can add costs to delivering care in those settings.”

DENIED CLAIMS

Patients can be at the mercy of insurance companies that deny claims for services they thought would be covered, and some fight their bills for years, believing that they should not be responsible.

Others just give up and pay, even though they share that belief.

Doni Gallinger of Portland did not give up, despite having claims denied by two insurance companies. But it took years for the 70-year-old to get coverage for mental health therapy.

“There was a very clear intent … to withhold services,” Gallinger said. “That was a very clear objective for them.”

The system is a perplexing mess, even for health care professionals.

Jill Copeland, a mental health therapist in Yarmouth, said she had to learn the ins and outs of how seven insurance companies conduct business in order to get properly reimbursed. If she didn’t have to spend so much time navigating the system, she said she could see 15% to 20% more patients.

“I have waited a very long time to get paid,” Copeland said. “And I am very persistent.”

Getting insurance companies to fix problems related to reimbursements is often difficult.

“My experience has been in general if they get things set up right the first time, it’s likely to keep going right,” Copeland said. “But if something doesn’t go right the first time, it feels like you might as well just give up. You can spend hours and hours and hours on the phone and be given all kinds of promises that it’s fixed and then it still isn’t fixed.”

UNPREDICTABLE PRICES

Patients trying to navigate the health care market find dramatically different prices among medical providers. Many learn the hard way.

In 2021, Alex St. Hilaire of Westbrook got a CT scan on his abdomen at Shields Imaging Center in Brunswick; it cost about $750. The next year he had the same exact scan at Northern Light Mercy Hospital – and it cost him nearly $3,000. With a high-deductible insurance plan, Hilaire is on the hook to pay most of that total. He had no idea charges for the same service could vary so much.

“I was literally in the machine 40 seconds tops, and it cost $3,000,” St. Hilaire said.

High charges are sometimes the result of a hospital rolling in other costs and services, said Christy Jolliff, Northern Light Health’s vice president of enterprise revenue cycle, who was speaking generally, not about St. Hilaire’s bill. If a bill shows $25 for a bottle of aspirin, that fee may actually cover other materials and services.

“We don’t charge for every piece of gauze, every Q-tip that’s being used,” Jolliff said. “Oftentimes, it covers things that don’t get listed at all.”

Why do hospitals charge so much? “Because they can,” said Jim Ward, president and principal of Patient Advocates, a Gray company that works with self-insured employers to lower health care costs.

Large organizations and insurance networks have the power to negotiate with hospitals, Ward said. Individual patients don’t.

Unlike neighborhood restaurants, hospitals generally don’t compete for business with customers. Rather, they are looking to cover many running costs.

“Hospital pricing is not the same as pricing for goods in a retail store in that it is not done looking strictly at what other providers charge,” said Swallow, the MaineHealth executive. “Rather, hospitals start with the premise that they must cover their operating costs – including free care and costs not fully covered by Medicare and Medicaid – and leave enough of an operating margin to weather future adverse events and invest in new technology and infrastructure.”

SHOPPING AROUND

There are ways to reduce the odds of an unexpected bill, but they don’t offer perfect protection.

The state’s seven-year-old CompareMaine website, launched by the Maine Health Data Organization, a state agency, allows patients to compare the costs of procedures like a colonoscopy or a knee replacement. The site reveals widely varying costs across the state – a hip replacement can cost anywhere from $23,000 to $57,000.

But the site doesn’t tell patients what facilities are in network for their insurance companies – information that can dramatically affect their share of costs. And it doesn’t help patients understand how to navigate their coverage plans to control costs. It won’t tell you, for example, that it is sometimes better for patients to meet their annual deductibles before scheduling elective surgery.

In an effort to increase price transparency, the federal government has mandated that hospitals publish the “chargemaster” prices, or list prices, on their websites.

But the chargemaster prices often have little to do with what patients get charged. The list price of repairing a broken wrist may be far different than what the various insurance companies, negotiating with hospitals, have agreed to pay for that surgery.

The bill a patient receives in the mail may be a full three steps removed from the chargemaster prices.

Stephanie DuBois, a spokeswoman for Anthem, said the company encourages its patients to shop around for health care services and call to find out what Anthem will pay.

“We all know a hospital setting can be one of the most expensive places to receive care, which is why at Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield we invest a lot of time and resources into educating consumers about the various choices they have available to them,” DuBois said in a written statement. “Services such as imaging, labs, or prescription drug infusion are available at many non-hospital based facilities that offer consumers a convenient location, a much lower cost, and equal, if not greater, quality.”

INSURANCE GAPS PERSIST

More Americans have health insurance now than ever before because of the Affordable Care Act, which took effect in 2013. Still, about 8 percent of Mainers remain uninsured. And many others are underinsured, with high deductibles or cost-sharing arrangements that shift more of the financial burden onto them.

The proliferation of high-deductible health plans – designed to keep premiums down – means patients are paying a higher share of the bills that come in when they get sick.

While medical bankruptcy is rarer than before the ACA took effect, many patients are saddled with thousands of dollars in bills that they are unable to pay.

Valerie Lawson, 65, of Calais said she was shocked by the $20,000 bill she received when she was temporarily uninsured last winter. She had dropped her insurance because the premiums were so high, and during that lapse she had to go to the emergency room because of hemorrhaging in her colon.

She learned what she owed when she was still weak and recovering at home. “I felt like the floor opened up beneath me, and I fell through,” she said. “I thought, ‘You have to be kidding me.’ I was really gobsmacked.”

Lawson said she gave up fighting what she believed were unfair charges and paid $14,000 to settle the bill because the fight took too much energy, and being uninsured she was in a poor negotiating position with Northern Light Eastern Maine Medical Center. She is now insured again.

But it’s not only people without insurance getting large bills. People who are underinsured – often with high-deductible health plans to keep monthly premium costs low – end up paying high-cost bills.The large number of underinsured people does more than land them with massive bills. It also contributes to inefficiencies in the health care system. The higher costs can make people reluctant to use their health care plans, delaying health services even when they need care, experts say.

“We focus on spending a lot of money later in the development of disease, when we should be focusing on prevention, early diagnosis and treatment,” said Reggie Williams, vice president of the International Health Policy and Practice Innovations program at the Commonwealth Fund, a foundation in New York City that supports health care reforms.

That increases the overall cost of health care and leads to worse health outcomes, such as higher rates of infant and maternal mortality, Williams said.

“The lack of investment we have in the United States before people give birth really impacts the quality of care people have while they are pregnant and postpartum,” Williams said.

REFORMS RESISTED

At the root of the problem is the way health care is financed in the United States. It is a system that is hard to defend, even for hospital administrators and insurance executives.

Yet it persists.

MaineHealth’s president, Dr. Andy Mueller, said the system needs to change, and he wants to enact meaningful reforms that would move payment models away from charging fees for services to paying health care providers for keeping people healthy. Mueller said the financial incentives need to move from volume charging for services to prevention and management of chronic conditions, early diagnosis and treatment – in other words, keeping people out of the hospital.

“We can’t accept the status quo,” said Mueller, who became the leader of Maine’s largest hospital network in 2021. “We need to fundamentally change the way we get paid.”

Mueller agreed that massive reforms would be daunting. But he said MaineHealth expects to launch some pilot programs later this year that could begin to make a difference. Details of the programs – which will require a waiver from the federal Medicaid program – will be released this fall.

“Rest assured, we are working on lots of reforms that will change how we deliver care while increasing affordability,” Mueller said.

But Jim Ward, the Patient Advocates president, said the headwinds against meaningful change are strong.

Any change has the potential to benefit one sector of the industry at the expense of another, and would face powerful resistance. “There’s a very strong established and vested interest in maintaining the status quo,” Ward said.

Some see the solution in a single-payer system – where the government pays for medical care, financed through taxes, eliminating much of the market for insurance companies. It would force hospital networks and other medical providers to accept prices set by the government – as they do with Medicare and Medicaid.

Other countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, France and Spain, and much of the developed world, have instituted single-payer systems or universal coverage.

Liberal politicians and advocates in the United States, such as Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, have long called for a single-payer model, which Sanders describes as “Medicare for all.” Conservatives have opposed the idea, calling it socialized medicine.

Other substantial but less sweeping reforms that are often discussed include lowering the age eligibility for Medicare from 65 to 55 or 50 and giving people a “public option” for health insurance. But action on such fronts does not seem to be on the horizon, and much narrower changes are hard fought.

Even a modest reform that attracted bipartisan support – letting Medicare negotiate prices with drug manufacturers – took decades of advocacy. The Medicare reform, which finally cleared Congress and was signed into law by President Biden last week as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, will also limit annual out-of-pocket prescription costs for Medicare patients to $2,000.

A proposal championed by U.S. Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, would have capped insulin copays at $35 per month. The Inflation Reduction Act that passed Congress included this copay limit for Medicare patients, but not for the rest of the population. Collins and other advocates hope to bring forward a separate bill to pass a broader insulin cap.

Woloson, executive director of Consumers for Affordable Health Care, said it’s difficult to enact reforms that benefit patients given the competing interests of the major players in the market, such as hospitals, insurance companies and drug manufacturers.

“When you adjust something over here, you have to adjust over there,” Woloson said. “The consumer is always left holding the bag. What works best for hospitals or insurance companies might not work for patients.”

Some have tried to reform the system at the state level. Massachusetts launched a system that sharply reduced the rates of the uninsured and inspired the federal Affordable Care Act. In recent years, the state established a health care cost commission, but it has little regulatory power.

Maryland has worked for decades to regulate costs and reduce incentives to over-treat patients. The state regulates and sets hospital prices and places all the hospitals under a single “global budget,” which means the finances for hospitals in Maryland are all lumped into one budget.

But Maryland’s efforts have yielded mixed results, according to recent studies.

Woloson said such efforts are important incremental steps, but they don’t represent substantial progress. “They’re not there yet,” she said.

Maine continues to study the feasibility of reforms. Last year, the state approved the Office of Affordable Health Care, which is studying a number of reform possibilities, including allowing people to “buy” Medicaid coverage, expanding Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program and further increasing subsidies for ACA plans using state dollars.

The reforms, like the Affordable Care Act, tend to focus on expanding access to insurance rather than addressing problems with pricing and out-of-pocket costs.

SINGLE-PAYER A TOUGH SELL

Pease, of Maine AllCare, the advocate for single-payer systems, said anything short of single-payer will always be lacking.

“In single-payer systems like Canada, the doctor sends off the bill for services to the government, and they get paid a few days or few weeks later,” Pease said. “It’s very automatic and removes inefficiencies. Insurance companies just add another layer of bureaucracy, denying payments, requiring prior approval of services. They’re the middleman.”

But no state has enacted a single-payer system, and the political climate does not appear conducive to a national single-payer system. Proposals in recent years to establish single-payer in Maine have stalled out on numerous occasions.

Vermont came close in the early 2010s, but ultimately abandoned it over the complexity of a small state going it alone and the difficulties in a state financing the system.

California is considering a single-payer system, but a bill to create one failed to get a vote in the state assembly this February.

Single-payer also may not be a panacea.

Mueller, the MaineHealth CEO, said that a single-payer system would not necessarily be an improvement. If the government did not put enough money into the system, there could be massive cuts to health care services.

The way it is now, if there are cuts in government-funded Medicare and Medicaid, health care systems have the flexibility to make up for lost revenue by increasing costs to private insurers.

Health care systems would potentially lose that ability under a single-payer system, Mueller said. So, if public funding for a single-payer system was insufficient or inconsistent, it could result in cost-cutting and ultimately a declining quality of health care, he said.

Dan Colacino, vice president of the Maine Association of Health Underwriters, which represents brokers that sell insurance, said the success of a single-payer system would be subject to the push and pull of state budget negotiations.

“It moves the cost of health care from individuals and employers onto the state,” Colacino said. “The increase in taxes would be huge.”

Without meaningful change, Maine patients are largely left to navigate the medical billing maze on their own, learning one painful lesson at a time.

Sean Dundon’s teaching moment came on Christmas Day, when he sliced off a portion of his thumb peeling potatoes. The trip to Northern Light Mercy Hospital for an assessment and a bandage – he didn’t even need stitches – cost him about $300 for the actual treatment and another $500 for a hospital facility fee he had to use his deductible to pay.

Dundon said the system is “intentionally obfuscating and confusing” and it shouldn’t be. “If there had been a sign on the wall that said there was a facility fee, I would have gone home, dressed it myself and gone (somewhere else) the next day.”

In their own words: Nine Mainers talk about their medical billing nightmares

To get a clearer understanding of the medical billing frustrations that affect so many people, we invited readers to share their billing and insurance problems with us. More than 100 people did. Here are nine of their stories.

BRIAN AND EVELYN ROACH

Evelyn Roach of Gray gave birth to her first child in October.

Eamon was born six weeks premature and needed to stay in Maine Medical Center’s neonatal intensive care unit for about two months. While he’s now healthy and at home, Roach and her husband, Brian, spent months fearing they would wind up hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt for their new baby’s medical care.

The couple brought Eamon home Dec. 31. They had set aside money for the pregnancy and birth because they have a high-deductible insurance plan and expected out-of-pocket costs totaling a few thousand dollars. But shortly after bringing the baby home, the couple got letters from her insurance company stating their claims were denied and that they would be on the hook for the full cost of his care: $360,000.

She and her husband made numerous calls to Anthem and MaineHealth, the parent organization of Maine Med. She said they never got a clear answer about why the claim was denied.

“It’s a massive amount of money. It’s almost incomprehensible,” Brian Roach said while still trying to get answers in May. “How would we go about paying for this?”

“No one (ever) said this is wrong and you won’t be charged for it,” Evelyn Roach said.

Finally, in June they got a bill from Anthem in Maine showing they didn’t owe any money. They had already met their out-of-pocket deductible of $6,600 earlier in 2021.

“We were so relieved,” Evelyn Roach said shortly after receiving the news. “It was adding unnecessary stress to an already stressful situation.”

But they still do not know why the claim was initially denied.

“It’s unclear to me what happened,” Evelyn Roach said. “Whenever I spoke with someone, they were always kind and trying to be helpful, but I could tell no one really could tell me what was going on.”

She said they notified the insurance within a week of Eamon being born that he was being added to her insurance policy, meeting that insurance requirement.

Evelyn and Brian have different insurance policies through their employers, so they think this may have been an effort by Anthem of Maine – Evelyn’s policy – to get Anthem of Illinois – Brian’s insurance coverage – to cover the birth. But no one has confirmed that.

Evelyn Roach said the experience made her feel helpless.

“Eamon needed to be in the hospital after he was born, and we shouldn’t have had this hanging over our heads,” she said. “Why was this so stressful and confusing?”

ALEX ST. HILAIRE

Alex St. Hilaire needed a CT scan twice in the past two years for abdominal pain he was experiencing.

The tests were identical. In both cases the 31-year-old’s symptoms turned out to be false alarms. But the two bills he received were starkly different.

In February 2021, St. Hilaire went to Shields Imaging in Brunswick for a CT scan and ended up with a bill of $742. Because he has a high-deductible health insurance plan, St. Hilaire knew he was going to pay the bulk of the cost, and the bill was in the ballpark of what he was expecting.

In February 2022, the Westbrook resident needed another scan. He was having difficulty scheduling one, so he asked his doctor’s office to give him other places to try. He was referred to Northern Light Mercy Hospital in Portland, where he went for the same CT abdominal scan conducted at Shields Imaging the previous year.

The cost: $2,900.

“I was expecting $600 to $700. I was not expecting $3,000,” St. Hilaire said. With the high-deductible plan, he was on the hook for most of the money, although he was able to get a discount to $2,500 by immediately paying in full.

All for a procedure that took less than five minutes.

“I remember the tech saying, ‘All right, done.’ I was literally in the machine 40 seconds tops, and it cost $3,000,” St. Hilaire said. “It didn’t ruin my year, but certainly I could have done something else with that money.”

St. Hilaire said it doesn’t make any sense that the same procedure could have such wildly different costs.

It’s a painful lesson learned by countless health care consumers in the U.S., where all kinds of medical costs vary widely for the same procedures. In Maine, for example, a hip replacement can cost $30,000 in one hospital and $60,000 in another.

“Why are we paying crazy bills like this?” he said.

ED LATHAM

When Ed Latham experienced chest pains in May, he checked himself into Northern Light Maine Coast Hospital in Ellsworth for observation.

The 53-year-old had three previous heart attacks, so he relied upon his cardiac surgeon’s “strong recommendation” that he be hospitalized for observation and tests. Latham said he was concerned about whether insurance would cover his six-day hospital stay, but he wasn’t going to go against his doctor’s recommendation.

“I understand their thinking of it’s better to be safe than sorry,” said Latham, who lives in Milbridge. “They didn’t want me walking out of the hospital and dropping dead on the street a few blocks away.”

Latham’s heart was OK, and he was released. A few weeks later he got a letter from his insurance company stating that the claim for his hospital stay would be denied and not covered. There was no explanation. After months of waiting, he received a few bills from the hospital totaling hundreds of dollars, but Latham said he has no idea if he’s getting more bills and could be on the hook for thousands in payments.

Latham said he called the hospital’s billing department, and they told him that it will likely be worked out between the hospital and Anthem, his insurance carrier. But in the meantime, the possibility that he could owe thousands continues to weigh on him – he still has not been told how much the bill could be.

“Why am I involved in this at all?” Latham said. “They shouldn’t be putting me in the middle of a dispute between the hospital and the insurance company about what is payable and not payable.”

Latham said the entire situation is alarming.

“The insurance company is essentially saying it is logical to go against your doctor’s wishes for their financial considerations,” Latham said.

DAVID SANBORN

Once a year David Sanborn of South Berwick gets an endoscopy for his throat to make sure a pre-cancerous condition doesn’t return.

And every year he has to fight with his insurance company over the bill.

His medical provider is in the insurance company’s network, but his doctor sends the biopsy to an out-of-network lab. His insurance company, Cigna, has billed him for the entire cost of the lab work – $4,300 – every year.

“Every single time it’s been a different problem, and every time they are trying to stick me with a lab bill,” Sanborn said. “Their policies are consistently changing. It’s aggravating. It’s a procedure I am going to need next year and the year after that and for the rest of my life. It should be paid.”

So far, the 46-year-old has been able to eventually get the cost covered. But he said it’s infuriating to have to go through the hassle every time.

Sanborn said he could have his doctor seek a different lab, but doesn’t want to compromise on his care.

“When my doctor decides this is the best lab to send the sample to, I’m not inclined to argue with my doctor,” he said. “He’s the expert.”

DONI GALLINGER

Doni Gallinger fought for years with two insurance companies over coverage for mental health services.

When the 70-year-old enrolled in Medicare five years ago, she also purchased insurance that provided supplemental coverage for mental health. Gallinger said she was assured that her therapist – Jill Copeland, a licensed clinical professional counselor – would be included in her insurance plan.

Nevertheless, Gallinger said, the companies denied the claims.

“They just wouldn’t bloody do it. They just wouldn’t,” she said.

Gallinger said she ended up having to pay $1,500 out-of-pocket before her mental health services were finally covered, but she spent many hours on the phone and writing letters to get the service covered. The hold-up was over the fact that standard Medicare does not reimburse for counseling by an LCPC even though her supplemental insurance plan was supposed to.

“The only answer I would ever get is that, ‘We won’t cover it because Medicare doesn’t,'” said Gallinger, who wrote letters to Sen. Angus King and to Rep. Chellie Pingree to put pressure on the insurance companies. “There was a very clear intent … to withhold services. That was a very clear objective for them.”

The only reason she eventually broke through and got it covered was by being extremely persistent with letters and appeals. In one May 2019 letter to Aetna, Gallinger was so frustrated that she wrote: “(May) God forgive you for harassing people with health problems, rather than giving them the services they have contracted and paid for.”

Gallinger, who lives in Portland, said that in all the time she has dealt with insurance companies, “they don’t ever seem to make mistakes where there’s a benefit in your favor.”

She lived in Canada as a young woman and remembers learning about how the U.S. system was so different from the simpler Canadian system, which covers people without sending them into medical bankruptcy.

“When I was in Canada, we always watched in horror what was happening in the U.S. (with the health care system),” Gallinger said. “We wondered why they put up with it. The system is barbaric.”

SIMONNE MALINE

Simonne Maline has osteoarthritis in both knees. She uses walking sticks to get around, and for more than a decade she has relied on periodic injection treatments to keep the pain manageable and avoid surgery.

Now, however, the 56-year-old is so far unable to get the same treatment that has helped her in the past because it may not be covered by her plan.

“It’s discouraging and frustrating and makes me angry that my life is limited because of insurance and money,” said Maline, who lives in Winthrop. “And it’s not even based on science. It boggles my mind. Life shouldn’t have to be this hard to get care.”

Maline said her insurance company turned her down two years ago when she requested SynVisc-One injections. She is being required to try another treatment first before her doctor can request the SynVisc-One injections again, and it’s not clear another request would succeed.

She fell on the concrete floor in her garage last fall, further aggravating her left knee. The treatment injects a gel that lubricates the knee. The company’s website says some insurance plans will cover the procedure, while others won’t.

The cost of a SynVisc-One is about $1,000 to $2,000 plus the cost of a health professional to give the injection. It’s far less than the $30,000 or higher price of knee surgery, which she said she will likely need if she can’t get the treatments.

The injections – which she has undergone three times in the past 15 or so years – have provided years of pain relief and mobility. But in recent years insurance companies have balked at paying for the treatments because it’s ineffective in some cases.

“I have a proven history of the treatments working for me, so this should be the first line of defense for me,” said Maline, who happens to be executive director of the nonprofit Consumer Council System of Maine, which advocates for improvements in public policy for mental health services.

Instead, she will have to try cortisone shots that, based on past experience, she believes will not work. If the gel injections are not approved after that, she will have to wait more than six months for knee surgery.

And not only would a knee replacement surgery be more costly for the system, but the recovery time from surgery would mean she could not care for her husband, who uses a wheelchair and is disabled from a brain injury. Knee surgery for Maline would mean her husband would need to go to a nursing home.

Maline also has about $25,000 in medical debt as a breast cancer survivor and needing three surgeries related to her cancer and other medical problems. For three years in a row, she hit her $7,000 out-of-pocket maximum with her insurance plans. So even though she’s insured, it’s put her into debt.

“When you look at what you have to pay out of pocket, it becomes a huge financial burden that becomes insurmountable,” Maline said.

VALERIE LAWSON

Valerie Lawson said she knew she was rolling the dice in early 2021 when she chose to be without health insurance temporarily.

At age 64 and only a year away from qualifying for Medicare, she could no longer afford to pay her health insurance premiums through the Affordable Care Act. A few weeks later, the Biden administration increased subsidies for middle-class people like Lawson nearing retirement age, and she quickly signed back up.

But during the month that she was uninsured, Lawson experienced hemorrhaging in her colon and had to be hospitalized at Northern Light Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor. Her condition didn’t require surgery, but the bill for a two-day hospital stay totaled $21,000.

“When I first heard the total amount on the phone, I felt like the floor opened up beneath me, and I fell through. I thought, ‘You have to be kidding me.’ I was really gobsmacked,” said Lawson, who lives in the Washington County town of Robbinston.

So Lawson – still weak from her hospital stay – took it upon herself to examine every aspect of her bill, to see what could be challenged.

“It was exhausting,” she said. “I was still quite ill. I couldn’t even stand up for 5 minutes at a time, I was so weak.”

She looked over the charges and found they were consistently higher than the official “chargemaster” prices published on the hospital’s website. The chargemaster prices are the initial price set by the hospital, but they are often different than the charges negotiated with individual insurance companies. In one case, an iron IV infusion to help speed her recovery cost more than $3,000, when the chargemaster price indicated it should have been only about $50.

“If I had known how much that was going to cost me, I would have said, ‘No, thank you, I’ll have a steak at home,” Lawson said. She said Northern Light never gave her a reason for the price.

The hospital offered her a 25 percent discount on the overall bill, which she took, and is now paying off about $14,000.

While Lawson now qualifies for Medicare – and with supplemental insurance shouldn’t have to worry about getting socked with any more giant bills – she said the money she spent means that she will have to delay her retirement from her work in website design.

“You really go through the wringer when this happens,” Lawson said. “It just grinds you down, just no way out of it. I eventually just gave up.”

SEAN DUNDON

Christmas 2021 started painfully for Sean Dundon.

He was at home in Portland doing some morning food prep. “The first slice of peeling potatoes, I sliced a portion of my finger off,” he said.

Dundon, 54, said he wanted to make sure it wasn’t a serious injury, so he went to the Northern Light Mercy Hospital Emergency Department in Portland. He said he would have gone to an urgent care center but they were all closed for the holiday.

“They gave me Lidocaine (anesthetic), cleaned out the wound, wrapped it up and sent me home in half an hour,” Dundon said. He didn’t need stitches.

“I came home and opened presents and thought, ‘This was great.'”

The bill arrived a few weeks later: $800, which included a $510 “facility fee” for using the hospital on top of about $300 in charges for the assessment and treatment.

“If there had been a sign on the wall that said there was a facility fee, I would have gone home, dressed it myself and gone (somewhere else) the next day,” Dundon said.

A facility fee is charged by health care providers to cover the expense of the overall services in the building, but insurance companies will often pay only a fraction of the fee, leaving patients on the hook for the bulk of the cost.

Dundon said he tried to appeal and negotiate a lower bill but was unsuccessful. With a high-deductible insurance plan, he had to pay the entire cost himself.

“They are basically admitting they are gouging me,” Dundon said. “It is intentionally obfuscating and confusing.”

BILL BARTLETT

Bill Bartlett’s doctor recommended he get a routine cardiac stress test.

So the 60-year-old from Kennebunkport called his insurance company in advance to find out how much it would cost, giving them the name of the York Hospital-affiliated doctor’s office to make sure it was in-network and wouldn’t cost too much.

The answer: He would be responsible for $45.

It sounded reasonable, so Bartlett went for the test at York Hospital in November. The test did not show any problems with his heart.

When he got the bill in February, it was for $858 – $45 for the stress test plus $813 that was tacked on for reasons that weren’t clearly explained.

When he asked what the $813 was for, Bartlett said his insurance company, Harvard Pilgrim, told him it was a hospital facility fee, an add-on because the test occurred in a hospital. And he was told the insurance plan doesn’t cover most of the facility fee. The total facility fee was $924. Harvard Pilgrim paid $111, and the $813 balance was charged to Bartlett. After months of back-and-forth, Harvard Pilgrim paid the bill, without explanation, in late July.

Bartlett said when he initially called to complain about the charge, hospital officials were at first vague about the $813 but later confirmed that it was a facility fee.

“When a patient receives services at York Hospital, their invoice will include a facility fee,” said Jean Kolak, a spokeswoman for York Hospital, in a statement to the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram.

“The amount of this fee is created, based on a variety of factors, such as the cost of staff, equipment, technology, medications utilized, supplies and in some clinical care areas, the acuity of the patient,” Kolak said. “Additionally, in cases where the physician/provider is employed directly by York Hospital, a separate professional fee will also be charged.”

Kolak said the cost of the cardiac stress test and all other services at the hospital are built into the facility fee, so it is incorrect to say the stress test cost $45.

Bartlett said he thinks he should have been told about the total cost when he called the insurance company to ask about the price.

“If I’m interested in buying a car, you don’t say, ‘How much are the tires?’ No, you’re asking what the whole price of the car is,” Bartlett said. “Harvard Pilgrim quoted me the price. Any additional costs are on them (York Hospital).”

Kolak said “payments for services are based on contracted rates with each payer” and that according to the contract with the insurance companies, and in the case with Medicare or Medicaid patients “we cannot waive patient responsibility” for charges.

The hospital offered to give him a payment plan, but Bartlett balked.

“Why should I go on a payment plan for something I don’t owe?” Bartlett said.

Bartlett refused to pay, and an initial appeal to Harvard Pilgrim was rejected before being paid in late July without explanation.

“They have these charges that are invisible to consumers,” Bartlett said. “This shouldn’t be my problem, I did my due diligence ahead of time to determine the cost. It’s not like I have some exotic disease. They should know what this is going to cost.”

Bartlett said that had he not been semi-retired and in good health, he may not have had the time and energy to fight the bill.

“I often wonder how many times medical providers send these bills out, and get a check back because nobody’s going to argue or spend the time to fight it?” Bartlett said.

America has a life expectancy crisis. But it’s not a political priority.

by Dan Diamond - Washington Post - December 28, 2023

The commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration had an urgent message last winter for his colleagues, brandishing data that life expectancy in the United States had fallen again — the biggest two-year decline in a century.

Robert Califf’s warning, summarized by three people with knowledge of the conversations, boiled down to this:

Americans’ life expectancy is going the wrong way. We’re the top health officials in the country. If we don’t fix this, who will?

A year after Califf’s dire warnings, Americans’ life expectancy decline remains a pressing public health problem — but not a political priority.

President Biden has not mentioned it in his remarks, according to a review of public statements; his Republican challengers have scarcely invoked it, either. In a survey of all 100 sitting senators, fewer than half acknowledged it was a public health problem. While recent federal data suggests that life expectancy ticked up in 2022, a partial rebound from the ravages of the coronavirus pandemic, no national strategy exists to reverse a years-long slide that has left the United States trailing peers, such as Canada and Germany, and rivals, such as China.

“I wish that life expectancy or health span were a fundamental political issue in the 2024 presidential campaign,” said Dave A. Chokshi, a physician and public health professor who formerly served as health commissioner of New York. “We’re not living the healthiest lives that we possibly could.”

The Washington Post spoke with more than 100 public health experts, lawmakers and senior health officials, including 29 across the past three presidential administrations, who described the challenges of attempting to turn around the nation’s declining life expectancy. Those challenges include siloed operations that make it hard for public and private-sector officials to coordinate their efforts, a health-care payment system that does not reward preventive care and White House turnover that can interrupt national strategies.

Many suggested the nation needed an effort that would transcend political administrations and inspire decades of commitment, with some comparing the goal of improving life expectancy to the United States’ original moonshot.

“We’re no longer an America that talks about building a national highway system or sending a man to the moon, and yet it’s that kind of reach and ambition that we need to have to tackle the declining longevity problem,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).

Experts, officials and lawmakers acknowledged that a political pledge to reverse the nation’s life expectancy slide could quickly backfire, given the need to focus on long-term goals that might not be reflected in short-term progress reports. A politician attempting to improve life expectancy could be out of office by the time improvements were detected.

“Politicians, in general, haven’t wanted to engage on this because it feels kind of squishy and the solutions don’t seem clear,” said Ashish Jha, the dean of Brown University’s public health school who this year stepped down as the White House’s coordinator of the national covid response.

In an interview, Califf confirmed he’d urged colleagues in “so many” meetings to take action on America’s eroding life expectancy.

The trend is “quite alarming,” the FDA commissioner said, sitting in his office in White Oak, Md., where he oversees the nearly $7 billion agency that regulates drugs, food and other common products used by Americans. “All of the leaders within the [Department of Health and Human Services] I’ve talked with about this.”

White House officials said the president and his team were focused on combating the “drivers” of life expectancy declines, pointing to efforts to reduce drug overdoses, create an office to prevent gun violence and other initiatives. A senior health official in the Biden administration said pledging to improve life expectancy itself “would have to be viewed as something for a legacy.”

“Maybe a second-term priority for Biden,” said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to speak frankly about internal White House operations.

No single reason explains why America’s life expectancy has declined, with chronic disease, poor nutrition, insufficient access to care and political decisions all linked to premature deaths. There also is no single strategy to turn it around — and no agreement on how to do it. Some public health leaders and policymakers have called for sweeping reforms to how the health-care system operates, while others home in on discrete factors such as lethal drug overdoses, which have spiked in recent years and received considerable attention but are not solely responsible for the decline in life expectancy.

The paralysis over how to address the nation’s declining life expectancy extends to Congress, where a handful of lawmakers — mostly Democrats — have repeatedly portrayed the slide as a crisis, but most other lawmakers have said little or nothing.

“We don’t talk about life expectancy, because it just makes it clear what kind of failed system we currently have,” said Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), who has repeatedly warned about the rise in premature deaths, including organizing a July 2021 Senate hearing on the issue. Just 11 of the panel’s 18 senators attended, several only briefly; just five asked questions.

“I talk to other senators about life expectancy data and watch their eyes glaze over,” Warren said.

The Post submitted questions about life expectancy to all 100 sitting senators, sending emails, placing calls and making visits to their offices. Forty-eight senators — including 35 Democrats, 11 Republicans and two Independents — said they agreed that declining life expectancy was a problem. Many of those lawmakers pointed to their own legislation intended to combat opioid misuse and address conditions such as cancer and other factors linked to causes of premature death. All told, the 48 senators cited more than 130 separate bills focused on health-care issues.

Despite the flurry of legislation, the nation’s progress on life expectancy has stalled, with the United States increasingly falling behind other nations well before the pandemic. No senator has crafted a bill specifically intended to improve life expectancy or create goals for health leaders to reach.

Lawmakers have also worked at cross purposes, with Republicans fighting Democrats’ efforts to enact legislation linked to gains in life expectancy, including efforts to expand access to health coverage and curb access to guns. Sen. John Neely Kennedy (R-La.), whose state had the third-worst life expectancy in 2020, about 73 years, recently suggested that life expectancy would even go up for young Americans.

“I mean, the life expectancy of the average American right now is about 77 years old. For people who are in their 20s, their life expectancy will probably be 85 to 90,” Kennedy said on “Fox News Sunday” in March. His office did not respond to requests for comment.

Other Republican senators or their staff suggested they did not have a view on the issue because the senator did not sit on a relevant committee.

Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.) has “no jurisdiction over this issue,” his office wrote in response to questions about whether Moran had views on declining life expectancy. Moran, who sits on the Senate panel that determines funding for health agencies, has cast votes on numerous health-care matters, including repeatedly voting to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

In the absence of national solutions, some officials pointed to local efforts such as a new initiative in New York, which has repeatedly pioneered public health improvements later copied across the country. City leaders in November pledged to raise New Yorkers’ life expectancy to a record 83 years, saying a coordinated approach could prevent premature deaths. Ashwin Vasan, the city’s health commissioner, testified in front of the city council, urging members to pass a law requiring the city’s health commissioner — including his successors — to work toward shared public health goals.

“This is a test for government. And I really am hopeful that New York City can pass that test,” Vasan said after his testimony, standing outside New York’s city hall.

‘Further and further behind’

Life expectancy in the United States was once a source of national pride — a reflection of civic improvements, medical advances and other investments that set the nation apart from other countries.

“The future of human longevity, especially for Americans, seems bright indeed,” then-Sen. Larry Craig (R-Idaho) proclaimed at a 2003 congressional hearing, where expert witnesses listed scientific and technological breakthroughs that they expected would soon push U.S. life expectancy past 80 years.

But even the most optimistic expert at the panel warned that America’s prospects could dim. James Vaupel, director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, urged federal officials to immediately prioritize a “real mystery”: the emerging international gap in life expectancy.

“The United States is doing so well on so many fronts, but it’s falling further and further behind on this critically important [measure], life itself,” Vaupel warned the Senate panel, imploring officials to “really start worrying about this.”

It would take about a decade before Vaupel’s warning was heeded. Policymakers instead were focused on a more urgent political priority related to life expectancy: the growing cost of having so many older Americans seeking services through programs such as Medicare and Social Security.

So when the Obama administration and congressional Democrats hammered out legislation that would become the Affordable Care Act — the sweeping 2010 law that expanded health coverage to millions of Americans and made other changes to the health system — there was little fear life expectancy would decline.

Bob Kocher, a venture capitalist who worked in the Obama White House as a health-care and economic aide, said one reason the crafters of the Affordable Care Act were so intent on “bending the curve” on health spending “was our belief that life expectancy was going to keep going up for the foreseeable future.”

By 2013, public health experts had begun issuing more prominent warnings about life expectancy, pointing to the rising number of opioid overdoses, suicides and other preventable deaths. Senior officials across the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations said they were aware of those concerns but that their focus was on improving discrete factors linked to life expectancy, not on the overall number.

“Every meeting at the VA was about ‘life expectancy,’ but I can’t tell you we put charts on the wall of ‘what’s the life expectancy of a veteran,’” said Robert A. McDonald, secretary of veterans affairs under President Barack Obama.

The nation’s current top health official, Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, told The Post he’s acutely aware of the life expectancy decline, calling it the “byproduct of some very serious problems” such as gun violence and drug overdoses. But he downplayed the need for a national strategy, saying there was no reason to declare a public health emergency as he has done with the coronavirus and opioid deaths, adding his agency lacked the power to reverse the trend.

“We are so disjointed as a health system in the country,” Becerra said, suggesting that the responsibility to address life expectancy fell on “many of us,” including state health directors.

While Biden hasn’t directly addressed declining life expectancy, some of his rivals have invoked it on the campaign trail.

“We used to think that life expectancy was just going to keep going up, and that’s just not been the case,” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) said in a CNBC interview in August, linking the decline to the pandemic, drug overdoses and other causes that began years ago. The DeSantis campaign did not respond to a request for comment about how the Florida governor would reverse the trend if elected president.

“If we had regulatory agencies that were actually interested in looking at data, we would be trying to figure out why the all-cause mortality [for Americans] has increased,” Robert F. Kennedy Jr., running as an independent in the 2024 campaign, said in an interview with The Post this summer. “These aren’t covid deaths.”

Political commentator Matthew Yglesias has repeatedly urged politicians to focus on life expectancy, saying that America’s decline reveals systemic problems that leave the country at risk. “Tackling America’s weirdly short life expectancy should be a priority,” Yglesias wrote in one 2022 post.

Although Yglesias has fans within the Biden administration who have sought his counsel after he has written about traffic safety and crime, his appeals on life expectancy haven’t led to similar invitations.

“I think it winds up being a harder topic for politicians to get their heads around,” he said, noting the array of factors that span agencies and administrations.

Califf said he’s keenly aware of his agency’s limits when confronting life expectancy.

FDA is one of the nation’s most powerful regulatory bodies — its staff often tout that they oversee about 20 cents of every dollar spent by U.S. consumers — and Califf is pursuing initiatives, such as banning menthol cigarettes and improving access to generic drugs, that fall in his agency’s purview. But FDA can’t control how hospitals and doctors get paid. It can’t craft legislation, such as curbing access to firearms.

“The highest cause of death in children is guns. That’s a fact,” Califf said. “That’s not something FDA can do something about.”

‘It’s a hard sell’

In Congress, a handful of members have insisted that lawmakers must focus on life expectancy, saying it’s a core responsibility.

“Sometimes, we may, in the midst of our work, lose sight of the big picture … to create a nation in which the people in the United States can live long, healthy, happy and productive life,” Sanders said at the 2021 Senate hearing he convened on lagging life expectancy.

There is a notable partisan split in how members of Congress view life expectancy and whether they say urgent action is needed. Just 11 of the Senate’s 49 Republicans told The Post they believed that declining life expectancy was a public health problem.

The lawmakers who portray the recent decline as a crisis are often Democrats from states with the highest life expectancy — such as Massachusetts (79 years in 2020, according to federal data) and Vermont (78.8 years). Meanwhile, GOP lawmakers representing some of the states with the lowest life expectancy — Mississippi (71.9 years), West Virginia (72.8 years) and Kentucky (73.5 years) — declined to comment or did not respond to repeated questions about whether the issue represents a public health problem.

“It’s a hard sell with senators who live in some of the lowest longevity states. And it breaks my heart,” Warren said.

A further complication: Senators concerned about declining life expectancy offer radically different prescriptions for fixing it.

Alabama Sen. Tommy Tuberville — one of the few Republicans whose office said he was “deeply concerned about this trend” — linked America’s decline to drug overdoses, suicides and alcoholism.

“The facts show clearly that this is being driven largely by an increase in deaths of despair, with fentanyl overdoses being the leading cause of death for Americans 18 to 45,” Tuberville spokesman Steven Stafford said in a statement, pointing to legislation to improve mental health funding and secure the Southern border.

In comparison, Sanders has repeatedly called for sweeping reforms, insisting in an interview that “a failed health-care system is tied into a corrupt political system dominated by enormously powerful corporate interests.”

Even Democrats in neighboring states offered significantly different diagnoses. In the eyes of Rhode Island Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D), the No. 1 cause of America’s life expectancy problem is clear: broken payment incentives for doctors and hospitals.

But Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) traced the life expectancy decline to loneliness.

“Americans are just much less physically and spiritually healthy than they have been in a long time,” said Murphy, who has proposed a bill to create a White House office of social connection.

Ten senators singled out the burden of chronic disease, echoing The Post’s own review, which found that among people younger than 65, chronic illness erases more than twice as many years of life as all the overdoses, homicides, suicides and car accidents combined.

New York’s state of mind

In New York, officials are trying to put a framework around those often abstract challenges. Vasan urged the City Council in November to support HealthyNYC, his agency’s initiative backed by Mayor Eric Adams (D) that seeks to avert about 7,300 premature deaths by 2030.

“We want New Yorkers to experience more birthdays, weddings and graduations, more holidays and holy days, more life lived,” Vasan told the lawmakers, citing targets for reducing chronic diseases, cancers and other drivers of premature death. Council members are considering legislation to ensure that future leaders stick to the commitments — a suddenly urgent need with Adams embroiled in a fundraising scandal.

“We wanted this to be something that outlives us, that actually helps people,” said Lynn Schulman, chair of the City Council’s health committee.

Vasan and Schulman said HealthyNYC can be a template for other cities — the latest effort in New York’s long history of trying to tackle life expectancy. Under former mayor Mike Bloomberg, the city raised cigarette taxes, banned smoking in workplaces and attempted to limit sale of large sugary drinks. When Bloomberg left office in 2013, New Yorkers’ projected life expectancy was 81.1 years — more than two years longer than the national average — compared with 77.9 years when he took office in 2001.

“If you want to live longer, you could move to New York — or just vote for me,” Bloomberg said in a speech to Democratic voters during his short-lived 2020 presidential campaign. (Public health experts have cautioned that it may take decades to fully understand the link between Bloomberg’s initiatives and longer life expectancy.)

But Bloomberg’s efforts provoked backlash from food-makers, industry groups and some elected officials. Even as New York took steps a decade ago to limit salt and soda consumption, GOP lawmakers in other states crafted legislation to prevent their own local leaders from taking similar steps.

The Bloomberg legacy “is not a torch anyone has really wanted to carry,” said Yglesias, warning that the former mayor’s public heath agenda would be politically difficult to replicate elsewhere. “Conservatives really don’t like it. … I think it’s fallen out of style on the left as well.”

Sanders, who has spent years pushing for sweeping changes to America’s health system and economy, said Washington’s work to boost life expectancy could begin with a simple framing device.

“The administration, the Congress should have upon their wall, a chart which says … ‘What’s our life expectancy now [and] how do we get up to the rest of the world?’” Sanders said. He pointed to Norway’s life expectancy of more than 83 years. “That should be our goal.”

Dan Keating contributed to this report.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2023/12/28/life-expectancy-no-political-response/

Another Blow for the National Health Service in England: A Doctors’ Strike

by Mark Landler - NYT - January 3, 2024

The young doctors’ walkout is planned for six days — their longest action yet — and could result in numerous canceled medical visits and surgical procedures.

Thousands of young doctors walked off the job in England on Wednesday, dealing another blow to the country’s already-reeling National Health Service and raising concerns about a cascade of canceled medical appointments and surgeries.

The strike, which started at 7 a.m. and was scheduled to last six days, would be the longest labor action yet by the doctors, who have been clashing with the government over wages and work conditions since December 2022. It comes at an especially difficult moment for the health service, when the flu and other illnesses are filling up emergency rooms, outpatient clinics and other medical facilities.

The junior doctors — qualified physicians who are still in clinical training — have been seeking a 35 percent wage increase, which they say is needed to counteract a more than 25 percent cut in real wages since 2008.

The government has settled pay disputes with nurses and ambulance workers, but its standoff with the union that represents the young doctors has been particularly intractable.