America's not-so-hidden public health crises

The new year is a good time to issue a report card on the health status of the American people. On every front, I marked the box that says "needs improvement."

I saw something extraordinary in the smart phone videos taken inside the burning Japanese airliner on Tuesday. Despite the dense smoke inside and shooting flames outside, no one panicked. Everyone followed instructions. And every one of the 379 passengers and crew got out alive.

I lived in Japan during the first half of the 1990s while serving as the Chicago Tribune’s chief Asia correspondent. Its economy, which only a few years earlier had been touted as the next world leader, had just suffered through a burst real estate bubble. The country was sliding into a deep recession, which was followed by two decades of no or slow economic growth.

Yet throughout what became known as Japan’s lost decades, unemployment rose only slightly. Its corporations and small businesses retained their employees to the greatest extent possible through reduced hours, hefty government subsidies and a gradual loosening of its “lifetime” employment system.

What did Japan’s frontline managers rely on through both these crises, whether they be flight attendants, government bureaucrats or business leaders? A public whose communal DNA included social solidarity, a social norm that teaches people to respect the lives of their fellow citizens. They seem to understand intuitively that by acting in concert and with purpose, whether it be in an immediate emergency or a long-term economic crisis, they will assure the greatest good for the greatest number.

In my recent review of a new book about our bungled response to the COVID-19 pandemic, I noted that over the past 3 ¾ years, social solidarity has been in short supply in the U.S. While historians can point to instances in American history when social solidarity reigned, it is in remission now.

A sizeable fraction of the American public responded to the COVID-19 public health emergency by pursuing their own agendas. Many individuals preferred preserving their personal freedoms (no masks, no social distancing, no shutdowns, no vaccines) over protecting others. Corporations profiteered. Politicians pandered.

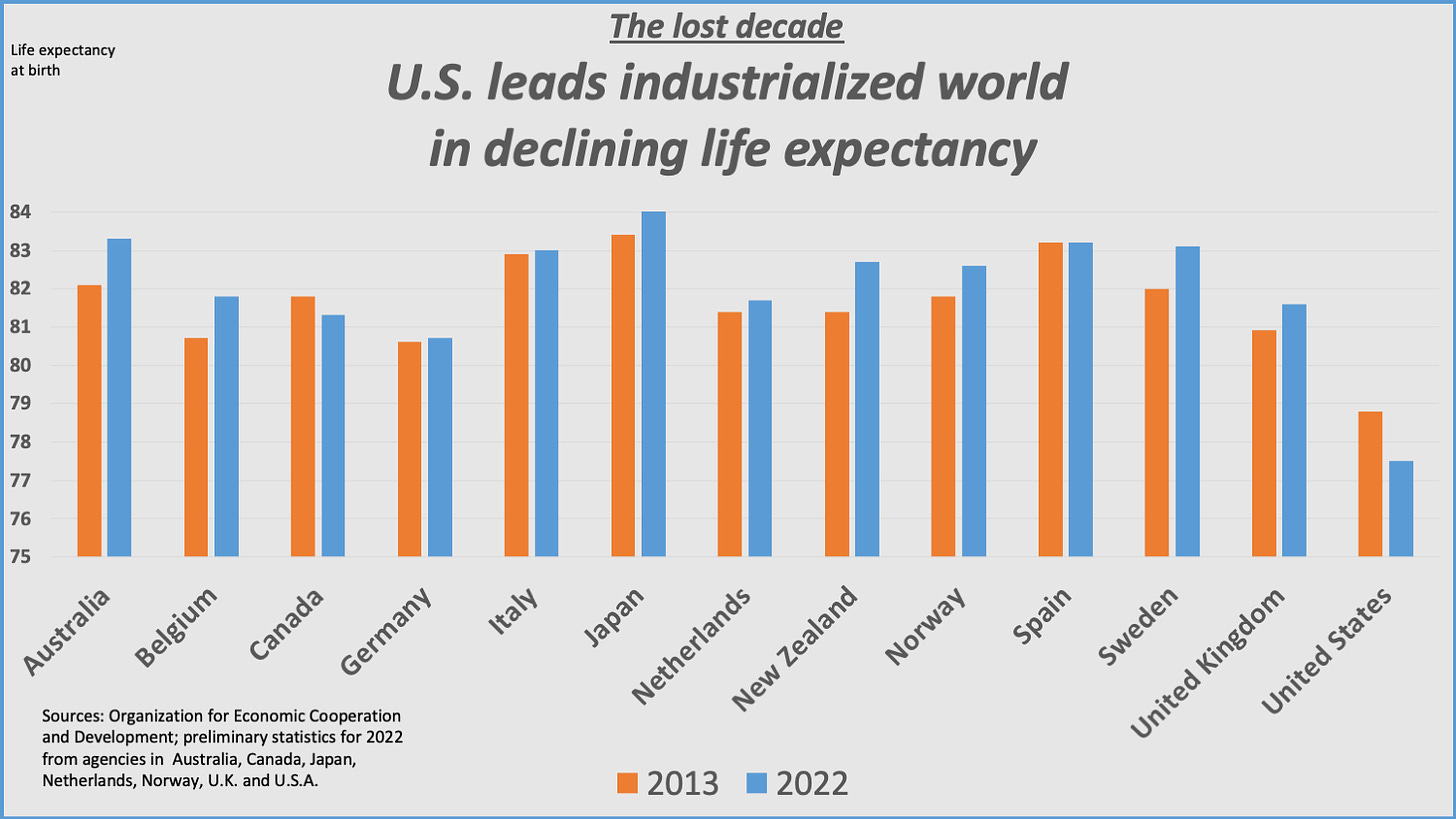

The results are still with us. U.S. longevity, already a laggard among industrialized economies in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, fell much farther than other countries during the pandemic. And it has recovered more slowly, remaining well below pre-pandemic levels (see chart below).

The report card

I am going to start this new year with an overview of the status of key public health indicators – a report card, if you will, on where we stand as a nation. It is a useful exercise because, as the Japanese taught us during our own years of industrial decline (after they learned it from an American industrial engineer named Edward Deming), you cannot improve what you do not measure.

Deming and the Japanese also taught us that the best way to achieve higher quality and better products is by making steady small improvements in both processes and products. This applies just as much to health care as it does to industrial and commercial activities.

A report card on public health sets the baseline for where we are. It also points us in the direction of where we need to go.

The current report card is damning. Our baseline is low. The distance to catch up with peer nations is far. The path upward begins with making steady small improvements.

Subject: Longevity

The decline in U.S. life expectancy compared to peer nations began long before the pandemic. In 1980, the year Ronald Reagan won the presidency, the U.S. was only two years behind Japan, then as now the country with the longest average lifespan. Today the gap is five years.

Digging beneath the surface of that single data point reveals an even more disturbing reality. People living in white, wealthier communities have a life expectancy that is not much different than those found in western European nations (though still behind Japan). People living in low-income neighborhoods of any color and Black middle-class neighborhoods often lag far behind. And people living in low-income Black neighborhoods have a life expectancy that is more than a dozen years behind white areas that are only a few miles away.

The racial gap began to shrink during the Obama administration. But the pandemic worsened the disparities. Between 2019 and 2021, the first two years of the pandemic, life expectancy fell 6.6 years in native American communities. Black and Hispanic life expectancy fell 4.0 and 4.2 years, respectively. Native American life expectancy is now 65.2 years, over 11 years less than white people. Blacks can expect to lead lives that are six years shorter on average.

Putting the U.S. on the upward path toward parity will require addressing the social conditions that drive ill-health. Food, housing and income insecurity are just as prevalent in the largely white, de-industrialized towns of middle America as they are in inner cities, even though a larger share of minority populations live under those conditions.

Programs that address the social determinants of health don’t have to be race-based to have a disproportionately larger impact on improving the lives and life expectancy of minority communities. For an excellent discussion of this point, and an introduction to the work of William Julius Wilson, whose books The Declining Significance of Race, The Truly Disadvantaged and When Work Disappears greatly influenced my own thinking in the 1980s and 1990s, read yesterday’s post by Matt Yglesias on Substack.

Subject: Infant Mortality

The nation’s infant mortality rate had been falling steadily for more than two decades – until last year. According to a CDC report released last November, there were 5.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2022, up from 5.44 deaths the previous year. That’s nearly 21,000 dead babies, lost either in childbirth or the first year of life.

But those decades of gradual improvement did not match other countries. Internationally, the U.S. ranked 12th highest in infant mortality among the 44 countries tracked by the OECD. We’re only slightly ahead of Bulgaria, but do worse than both Russia and the People’s Republic of China.

As Dr. Elizabeth Cherot, CEO of the March of Dimes, told the AP: This first uptick in years “underscores that our failure to better support moms before, during, and after birth is among the factors contributing to poor infant health outcomes.”

Subject: Obesity

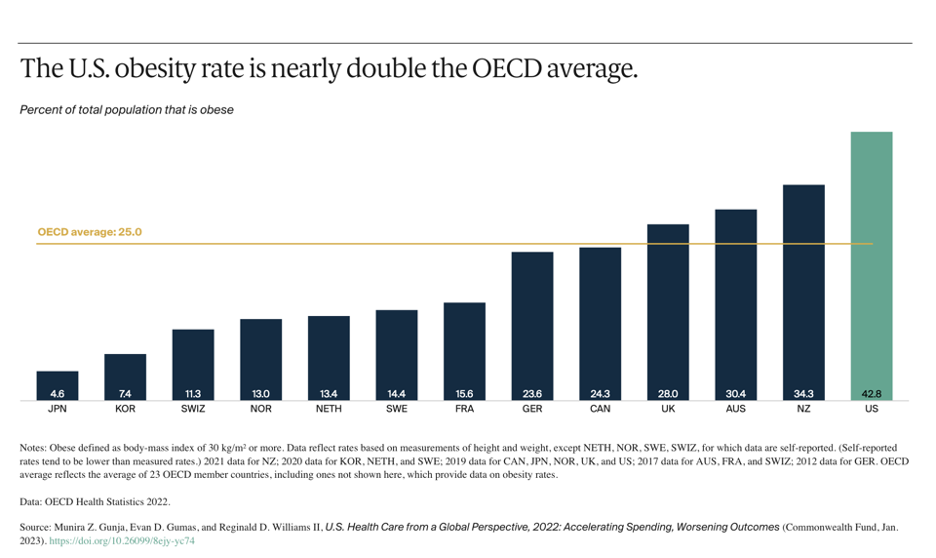

America’s collective waistline has been expanding for a long time. Obesity prevalence rose to 42.8% of the population in 2021, up from 30.5% two decades earlier. Severe obesity nearly doubled during that period and now hobbles 1 in every 11 Americans.

Obesity is a major risk factor for heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and kidney disease, which are half of the 10 leading causes of death in the U.S. The rate of diabetes, which is the disease most directly related to obesity, grew from 10% to 13% of the population in the past two decades. A third of adults have elevated blood sugar levels and are classified as pre-diabetic.

The CDC estimates the U.S. health care system spends $173 billion a year treating the medical conditions caused by obesity. Each obese individual incurs annual medical costs that are $1,861 higher than people with a healthy weight.

The medical research establishment, drug and device companies, patient advocacy groups and the press pay enormous attention to developing new treatments for each of these obesity-related diseases. The same is true for treating obesity itself. On any given day, I can read at least one article about the new weight loss pills or bariatric surgery.

Almost no attention is paid to obesity’s underlying causes. Americans today are living sedentary, screen-focused lives, both at home and at work. Many schools have cut or reduced physical education requirements. Few corporations offer mid-day physical activity breaks or gym membership benefits.

Fewer and fewer jobs involve intense physical activity. More and more farmers, truck drivers, machine tenders, office workers, and call center operators spend their working hours sitting, and then return home to do the same thing.

Our food and restaurant systems produce and market an inordinate amount of junk food, sugar-laced drinks and calorie- and carbohydrate-dense meals. Daily calorie intake has fallen slightly in recent years but is still 20% higher than the average American diet of 1960. The government’s agricultural programs subsidize the crops that fuel that unhealthy diet, not to mention feeding the cattle, pigs and chickens that not only lard our diets with artery-clogging saturated fats but despoil the environment.

No president since JFK has made physical fitness a national priority. Two recent presidents – Donald Trump and Bill Clinton – were significantly overweight and used their time in the bully pulpit to make a public display of their unhealthy eating habits. Meanwhile, Congress does nothing to redraw the nation’s skewed agricultural support programs, which are subsidizing the nation’s farmers to produce unhealthy food.

The government does require chain eateries to list calorie counts on menu items. But it doesn’t appear to have embarrassed anyone into changing their offerings or the choices made by their customers. Would you like sprinkles on that Mocha Cookie Crumble Frappuccino (590 calories)?

Subject: Unintentional Injuries and Violence

As the COVID-19 pandemic wanes, unintentional injuries will once again become the third leading cause of death in the U.S. after heart disease and cancer. Accidental poisoning (including opioid overdoses), motor vehicle accidents, drownings and falls killed over 224,000 Americans in 2021, the highest number ever. Poisoning deaths accounted for nearly half the total.

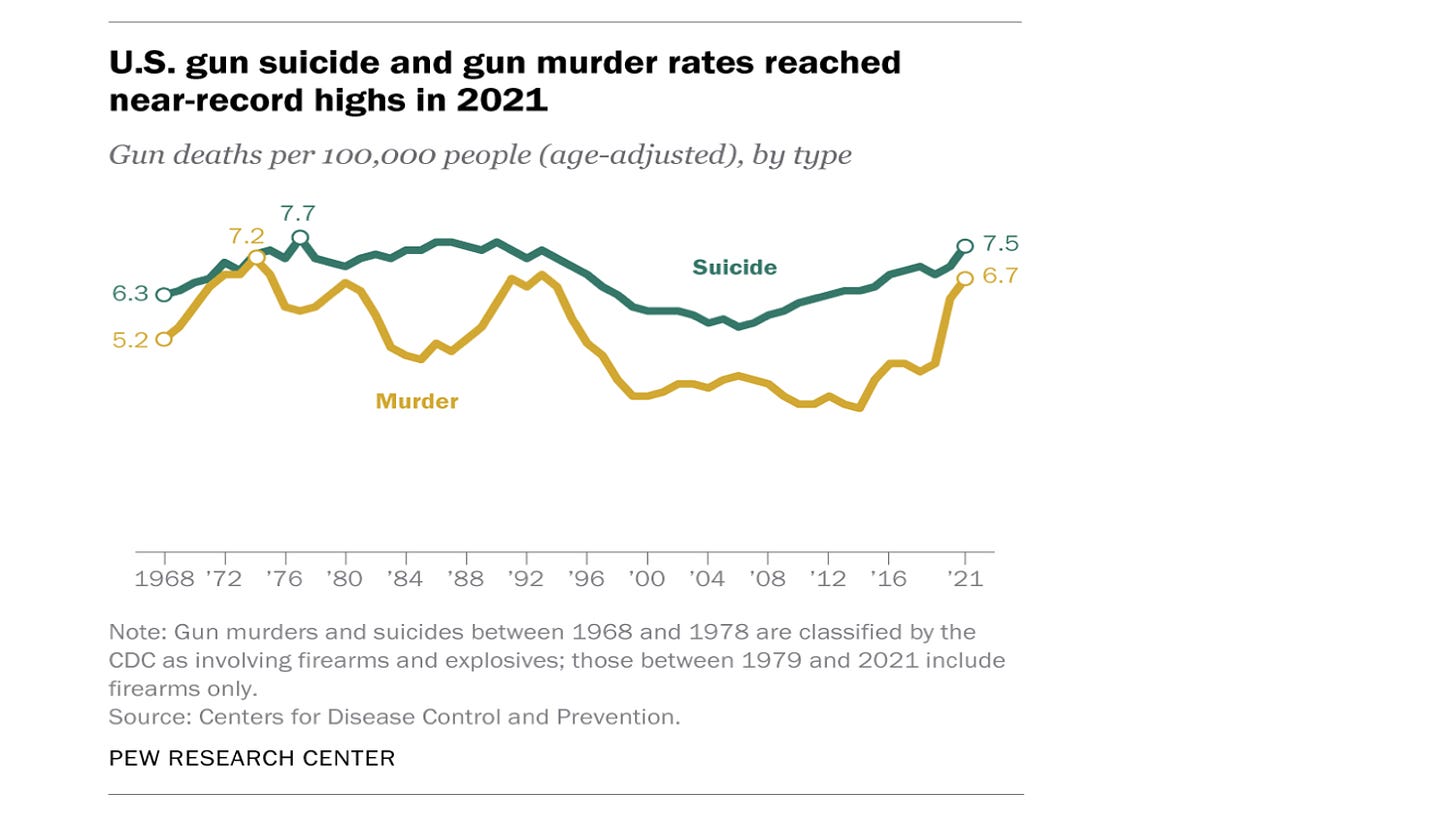

While opioid overdose deaths have leveled off in recent years at about 17,000 annually, the same can’t be said for victims of gun violence, which took 48,830 lives in 2021. More than half of those deaths were self-inflicted. Another 43% were murders. Just 537 deaths or 1% of the total involved law enforcement officers.

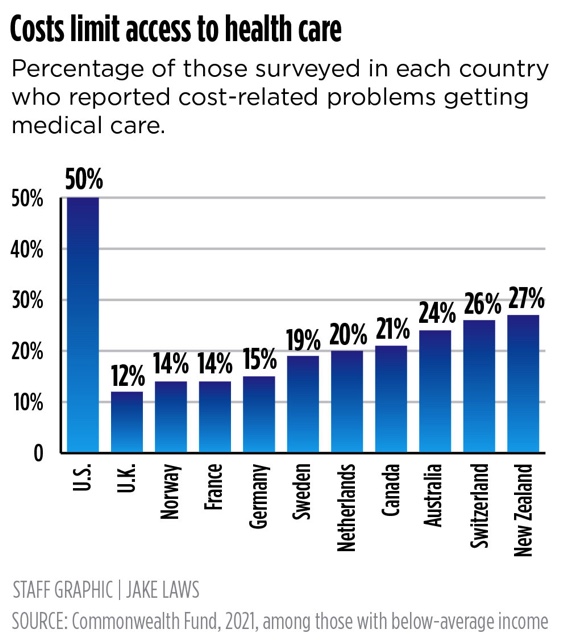

The U.S. has the highest suicide rate among all high-income countries in the OECD. Our rate is double that of the U.K., according to the Commonwealth Fund. One simple fact accounts for this dubious distinction. Nearly 8 in 10 suicide attempts here involve a gun, which is nearly always fatal. Self-administered drug overdoses – the preferred method in countries where guns are not so prevalent – are much less likely to succeed.

Much can be done to lower the accidental death rate in the U.S. First and foremost, something has to be done about the proliferation of guns in our society. It is tragic that our politicians can’t bring themselves to reinstate the assault weapons ban, whose removal in 2004 enabled a growing number of ideologically motivated or deranged killers to murder dozens of people in a single incident. If Congress can’t even do that, what hope is there of doing something about the proliferation of handguns, which have driven the murder and suicide rates to levels not seen since the mid-1970s?

The path forward

We’re at the beginning of an election year. I predict none of the issues outlined here will be given serious attention by either the campaigns or the media. In the years just prior to the outbreak of the pandemic in February 2020, economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case called attention to the “deaths of despair” – the opioids overdoses, suicides, alcoholism and gun violence deaths – that are ravaging so many communities and lowering life expectancy in the U.S.

Heard much about that lately? In a way, it’s odd that we haven’t because these are the social conditions that laid the groundwork for the rise of the Trump-led mob that now controls the Republican Party.

In the coming months, epidemiologists at the CDC, whose work this report card uses, will give us new data from which to measure progress from this baseline. Will 2024’s reports mark the start of a turnaround? I doubt it.

No interest, much less help, will be coming from Washington or the campaign trail. The headlines will be dominated by the atrocities and war crimes perpetrated by Israel in its war against Hamas, which provoked the conflict with the worst mass killing in Israeli history; Russia’s merciless invasion of Ukraine, which seems to be escalating daily; the rise and looming triumph of an openly authoritarian and extra-legal movement within the Republican Party; the divisions within the Democratic Party; and the media’s endless and mindless horse race coverage of the polls and primaries ahead of an election where American democracy faces its gravest existential threat since the Civil War.

The deteriorating health of the American people doesn’t stand much chance of breaking into the public’s consciousness in the face of these escalating crises. Yet people who care about public health must soldier on, doing what they can to make small incremental improvements. Here’s hoping the new year will see progress on every front.

GoozNews is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Private equity firms are gnawing away at U.S. health care

Not long ago, a colleague of mine sold his small cardiology practice to a private equity firm. He had started his practice in Florida nearly two decades ago, and when a purchaser first came knocking, he turned them away. He loved his independence.

But soon, he was persuaded to hand over the keys for two reasons: The price he was getting was very good, and he was happy to outsource the headache of running the business (managing billing, making sure there was adequate coverage for nights and weekends, etc.).

My colleague is not alone. The number of private equity firms has exploded in health care in recent years, spending hundreds of billions of dollars to buy physician practices, hospitals, laboratories and nursing homes. It’s a trend that should have everyone’s attention, from politicians to patients, because it can significantly increase costs, reduce access and even threaten patient safety.

At first, little changed after my colleague sold his practice. He drove to the same office and cared for the same patients. He went home unworried about who was on call or whether they were getting the billing right.

But over time, he started noticing small changes — the gentle nudge to bill more intensively for visits, to send more patients to the hospital for additional tests. Then, he noticed more profound changes: His practice stopped accepting a major insurer in the area (the private equity firm negotiating the contract couldn’t come to terms with the insurer), shutting out some of his long-standing patients.

This is happening across the country. First, private-equity-managed providers become more “efficient,” with fewer employees and more streamlined processes. Efficiency is not necessarily a bad thing; a lot of health-care organizations are run poorly. But what often follows is more aggressive billing and more requirements for patients to get tests done and the like, driving up health-care costs.

These firms often thumb their noses at consumer-protection regulations. Recently, the Federal Trade Commission accused the firm Welsh Carson of buying up small- and medium-sized anesthesia practices in Texas to gain so much market power it could charge insurers monopolistic prices, which are, in the end, paid by the employers and employees, not insurance companies.

There is also evidence that private equity acquisitions are affecting patient care. A study published in JAMA examined more than 50 hospitals that had been bought out and found that they saw a 25 percent increase in adverse events, such as hospital-acquired infections or falls, than non-private equity-owned hospitals.

Why would an acquisition from a private equity firm lead to more adverse health outcomes? After all, the doctors and nurses likely haven’t changed. Well, two key things drive safety in hospitals: The first is staffing levels (particularly nursing), and the second is detailed patient safety protocols and processes to prevent errors. Both cost money, and it is not a stretch to connect cuts in staffing and a reduced focus on patient safety with an increased risk of harm for patients.

Is it time to ban private equity in health care? No. Private equity is as much of a symptom of the health-care industry’s woes as it is a cause. There are other bad actors as well, including large health systems and others who are buying up physician practices and driving up prices. Lots of hospitals are failing to attend to patient safety, even without the involvement of private equity. So a ban, while attractive, would likely not solve the problem.

Instead, we need a three-pronged approach: First, we need more robust enforcement of antitrust rules to make market consolidation and monopoly pricing less attractive. This would reduce the incentive of private equity firms to buy up these practices and save consumers money.

Second, regulators — particularly Medicare — need to provide a lot more oversight over private equity acquisitions and similar purchases of health-care practices. This should include making sure these transactions don’t raise prices or affect quality of care.

Finally, we need real action on patient safety. Tens of thousands of Americans are dying needlessly in hospitals from preventable infections, medication errors and other causes. While health care has made strides in reducing errors, that progress is uneven. Medicare and other payers — as well as regulators — need to be far more forceful in ensuring that providers don’t shirk their duty to keep patients safe. This is especially true of private-equity-owned practices, but it extends beyond them as well.

My colleague who sold his practice to private equity has mixed feelings about what happened. While his life got simpler, he worries he can’t deliver the same quality care he did before. Policymakers should be worried, too. Without greater enforcement of antitrust rules and oversight of providers, our health-care system will become even more expensive and quality of care will deteriorate. Our country can’t afford that.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/01/10/private-equity-health-care-costs-acquisitions/

FDA to allow Florida to import prescription drugs from Canada

by Daniel Gilbert - Washington Post - January 5, 2024

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a Florida program that sets the stage for the state being able to import certain prescription drugs from Canada at a lower cost, the agency said Friday.

The FDA’s decision came in response to a proposal from Florida, under a law that allows states or Indian tribes to import prescription drugs from Canada if it reduces costs to American consumers without creating other health and safety risks.

“The FDA is committed to working with states and Indian tribes that seek to develop successful section 804 importation proposals,” Robert M. Califf, FDA’s commissioner, said in a statement. “These proposals must demonstrate the programs would result in significant cost savings to consumers without adding risk of exposure to unsafe or ineffective drugs.”

Before Florida can import drugs from Canada, it has to submit information for FDA’s review and approval regarding the specific drugs it seeks. Florida, in turn, will be responsible for ensuring the integrity of the supply chain, reporting when patients have bad reactions to drugs and complying with recalls.

The Florida governor’s office didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

The New York Times first reported the FDA’s decision.

The FDA’s move comes at a time of intense focus by the Biden administration to tackle the high price of prescription drugs, and as major players in the pharmaceutical industry are also shifting their strategies in an aim to make drugs more affordable and accessible.

Eli Lilly said Thursday that it would provide its popular weight-loss and diabetes drugs directly to patients through a telehealth service, an uncommon move for a drugmaker, in a bid to make it easier for patients to access its medicines. CVS said last month that it plans to revamp drug pricing at its vast network of pharmacies starting in 2025, a shift that industry analysts said could have far-reaching effects on what consumers pay for prescriptions at the counter.

The Biden administration, too, has launched various efforts to tame the high cost of prescription drugs, from studying new models to lower costs for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, to the Federal Trade Commission adopting a more aggressive posture on pharmaceutical mergers. The administration’s biggest such push is the Inflation Reduction Act, which will set a maximum price for how much drugmakers are reimbursed for certain drugs through Medicare.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/01/05/fda-florida-prescription-drugs-canada/

A Factory in Maine Proves ‘Made in America’ Is Still Possible

by Rachel Slade - NYT - January 5, 2023

Growing up, my parents drove my brothers and me around in lumbering Fords and ungainly Oldsmobiles until one fateful day in the summer of 1980, when my dad showed up in a brand new, all-beige VW Rabbit. It was a completely foreign thing, something from the future, a compact — perish the thought — German automobile. Buying a European car was now OK, my dad made a point of telling us, because this one was made in the U.S.A.

I inherited my father’s “made in the U.S.A.” credo, obsessively hunting for labels, flipping over plates and chairs and turning clothes inside out to find a country of origin. Which is how, over the ensuing decades, I became exquisitely aware that much of the stuff I bought was no longer made in the U.S.A. Everything from my Gap sweatshirts in the ’90s to my clunky desktop in the early aughts, and eventually to my refrigerator and dishwasher, was made elsewhere.

What happened to manufacturing in America and the environmental and economic consequences of offshoring — companies sending their manufacturing abroad — is a story we think we know. The demise of American production seems inevitable, the result of the rise of globalization and free trade. But now we are learning that the precipitous decline was the result of a steady, concerted, decades-long effort among power brokers to wrest the economy from a worker-dependent model to one where skilled workers are expendable. Corporate executives sold free trade to policymakers as a way to lower consumer pricing, but the human and political costs of offshoring were high.

By 2020, bringing back manufacturing to America seemed pointless, like investing in rotary phones. But when Covid shut down the country in March of that year, Americans were confronted by empty supermarket shelves. Later, the larger, more chronic impact of the pandemic was deeply felt in industries that relied on expansive, complex international supply chains.

That summer, I met Ben and Whitney Waxman, husband-and-wife co-founders of American Roots, who had been making all-U.S.-sourced clothing like hoodies and quarter-zips in Westbrook, just outside of Portland, Maine, since 2015. When the country hit pause, the Waxmans worried that demand for their wares would dry up. Without revenue to pay the rent on their factory space and their workers’ salaries, they knew that they’d lose their company in a few months.

To avoid that fate, they could make things the country desperately needed: masks and face shields. So the Waxmans asked their workers if they would be willing to return if they did all they could to make the factory safe. It was a big ask — vaccines were still a year away and information about how the virus spread was limited. In spite of the risks, every single employee said yes, energized by the idea that they could make a real difference at a moment of crisis.

The Waxmans shut down their factory to retool it for safe mask production. By that summer, they nearly quintupled their staff from 30 to 140-plus workers who were cranking out tens of thousands of American Roots’ custom-designed face masks for emergency workers and employees across the country.

Ben and Whitney had founded their company with a mission: to prove that capitalism and labor can work together to create community, good jobs and great products. They chose apparel making because it was fairly easy to get into and all components could be sourced domestically. All they needed was a few sewing machines and an army of workers willing to show up day after day. For these reasons, apparel manufacturing was one of the first industries to get offshored when tariffs were dropped following the signing of NAFTA in 1992. As a Maine native, Ben believed he was bringing back that lost industry — the state had once been a textile powerhouse — and through his mother, who had founded a locally sourced blanket and cape business, he had connections to get them started.

I needed to know how the Waxmans made the whole thing work. But first, their company had to survive the pandemic. I followed them through the fall of 2020, as demand for American-made masks dried up when imported masks began flooding in again. That year, they tripled their annual revenue, hitting $3.6 million. I was with them through 2021, as they returned to the hard work of rebuilding their hoodie business. They struggled to find buyers for their apparel in a wildly uncertain time, forced to shrink their labor force to 45 while just clearing $2 million in revenue.

I spent time on the shop floor and in the homes of their dedicated workers, many of whom are new Americans, who, with their families, had fled untenable, dangerous situations in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Angola and other countries, and had found themselves in Maine, eager to build new lives there.

While I was learning about the ups and downs of the textile and apparel industry, I was also introduced to labor history. Ben Waxman had spent a decade at the A.F.L.-C.I.O., the largest federation of unions in the country, representing 12.5 million workers, working closely with President Richard Trumka. During that time, he witnessed the impact of offshoring with his own eyes, standing shoulder to shoulder with factory men and women as their livelihoods were shipped abroad and their pensions dwindled.

Haunted by what Ben had seen, he and Whitney made sure their employees were unionized from the get-go, that their workers earned a living wage, and received health insurance, vacation time, and sick leave to care for themselves and their families. “Our company’s economic philosophy is ‘Profit over greed,’ ” he told me. “We have to make a profit, but it will never be at the expense of our workers, our values or our products.” In that way, the Waxmans were well positioned to attract and retain a work force in a tight labor market.

Since founding American Roots, Ben and Whitney have helped to lift families out of poverty by offering a pathway to the middle class through manufacturing. And they’re not alone. Small manufacturing shops across the country are doing just that at this very moment.

What I learned, however, is that what the Waxmans are doing is almost impossible. The deck is stacked against them. Every day is a struggle. Sourcing American-made components — cotton fleece, zippers, drawstrings, buttons — is a constant issue, because the apparel industry has shrunk considerably. Finding and training workers requires a huge investment in time and resources. Like many business founders in America, the Waxmans are also constantly searching for the kind of deep-pocketed financing deal that will allow them to build enough inventory to relieve them from the stress of made-to-order manufacturing.

The good news is that there are still people making things in the United States. In fact, American-made goods account for 24 percent of the G.D.P. More than 15 million people worked in domestic manufacturing in 2022, many in small shops across the country, producing everything from zippers to socks to textiles to, well, anything you can imagine.

It has taken us a long time to fully absorb the loss of manufacturing on a cultural level. Fortunately, these days, “made in the U.S.A.,” which for so long felt like an archaic rallying cry, more cynical than a comprehensive movement, offers Americans much more than the return of manufacturing jobs. After years of ceding the actual making of the things we use to other countries, the self-sufficiency and innovation that could come with bringing production home cannot be overstated.

During this presidential election year, there will be a lot of talk about American-made. The administration’s four-year agenda has been geared toward rebuilding our capability to manufacture high-tech products, while Republicans are appealing to their base of disenfranchised voters whose lives were affected when manufacturing went overseas.

But what do manufacturers really need to build a resilient domestic supply chain? Topping their wish list is universal health care, which would unburden small manufacturers of approximately $17,000 per worker with a family per year, allowing American companies to compete with foreign producers, especially the technologically advanced European factories which are attracting high-end brands looking to make quality products closer to home.

But we also need to talk about formulating a new industrial policy, just as Alexander Hamilton and George Washington did at the moment of the country’s founding. A manufacturing-first agenda, one not just focused on green energy production and chip manufacturing, would funnel government resources toward policies that manufacturers need to remain robust. That includes job-training programs, transportation infrastructure, research and development funding, sectorwide coordination and financing support in every industry. The policy would also take a hard look at tariffs and intellectual property laws to protect American innovation, and encompass broad, clear guidelines for collective bargaining and environmental standards.

Shifting this country back to making things requires cleareyed policy that would stimulate all kinds of production that would, in turn, lift up those abandoned by the new tech and service economy. But there are so many additional benefits. Manufacturing jobs pay better than average and require less education for entry than many other industries. Apprentices learn their craft by doing. Manufacturing also offers diverse opportunities for people who aren’t so inclined to sit in front of a computer eight hours a day. We’ll need programmers, machinists, inspectors, thinkers, inventors, tinkerers: people who enjoy building things and working closely with machines that move and learn.

Further, domestic manufacturing would stimulate innovation. Inventive thinking doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It usually comes after much trial and error, with designers and makers working side by side. In other words, proximity promotes innovation. Pharmaceuticals start with bench research in a lab. Polar fleece — a game-changing synthetic fabric designed to be lightweight yet warm, even when wet — was the result of a collaboration between Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, a Maine native, and a family-owned mill in Massachusetts. The first Apple Macintosh computer, with its user-friendly, intuitive operating system, was built by people experimenting with hardware and software until they arrived at something absolutely revolutionary.

And sometimes you don’t even know what you’re looking for until you’re deep in the process of making. While building equipment to launch Americans into space, NASA engineers contributed to the early development or invention of early LEDs, CAT scans, modern water purification systems, and the computer mouse.

In telling the American Roots story, I found that the most difficult part was finding an ending because manufacturing never ends, unless your company fails. In 2022, American Roots rebranded while the Waxmans hunted for deeper sources of financing that would help them scale up. They hit the $3 million mark in revenue that year and survived the highs and lows of 2023. As we step into 2024, Ben and Whitney Waxman and their team are still manufacturing rock-solid hoodies with heavy metal zippers — made in L.A. — big enough to grab with a pair of welders gloves.

And my dad? He now drives a Subaru Outback, proudly made in Lafayette, Ind.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/05/opinion/american-manufacturing-apparel-clothing.html

|

|

|

|

‘Giving us oxygen’: Italy turns to Cuba to help revive ailing health systemAngela Giuffrida in Polistena - The Guardian - January 16, 2024 In the operating theatre at a hospital in Calabria, Asbel Díaz Fonseca and his team are preparing to perform abdominal surgery on a man in his sixties. They deliberate over which medical technique to use – the French or US model – before deciding on the latter. But their main topic of pre-op conversation is food, namely which pizza is best: Neapolitan or Calabrian. There are subtle differences between the two, they say, but with a Neapolitan medic in the room, diplomacy prevails and they conclude that both types taste as good as each other. This may not sound out of the ordinary for Italian chitchat, but Fonseca is not a local man. He has worked at the Santa Maria degli Ungheresi hospital in Polistena, a town surrounded by mountains in the southern Italian region, for a year. But he is originally from Cuba. The 38-year-old surgeon is among the hundreds of health workers from the Caribbean island brought in to fill a drastic shortage of doctors across Calabria, one of the poorest regions in western Europe. “The main principles of our training are solidarity and humanity,” said Fonseca. “We take our skills to countries in need, especially where the health system is suffering. Italy has good doctors and all the right technology, but is lacking professionals in many specialties.” Two nationwide strikes in December brought the myriad issues blighting Italy’s healthcare system to the fore. Spurred by government proposals to reduce pensions, the 24-hour strikes reignited the debate over gruelling shift patterns and poor pay amid an exodus of staff. The coronavirus pandemic was the catalyst for many to leave; more than 11,000 health workers have left the public system since 2021. Italian medics were frontline heroes when the country became the first in Europe to be engulfed by Covid-19. However, the fines issued to some for flouting overtime rules during the pandemic were a reflection of how quickly their efforts were forgotten. Stressed medical professionals are now either retiring early, switching to the private sector, or seeking better opportunities abroad. In Italy’s poorer south, the public health system had endured neglect for years before the pandemic, with severe cost-cutting leading to the closure of dozens of hospitals. The mafia and political corruption have also taken their toll on services. Polistena has a population of almost 10,000, but its hospital, one of the last surviving in the area, serves 200,000 people in towns across neighbouring provinces. To remedy the problem, Calabria’s regional government called on Cuba, famous worldwide for dispatching medical brigades to assist with saving lives, most often during times of humanitarian calamity. The pandemic paved the way for the first missions to otherwise prosperous European countries – specifically to Bergamo, the northern Italian province that experienced one of the deadliest outbreaks of Covid-19, and Andorra. Portugal has also recently sought Cuban reinforcements after suffering shortages. Almost 500 health workers from Cuba, covering all specialisms, are now scattered across hospitals in Calabria. Eighteen are in Polistena. The Cuban assistance was initially met with scepticism from the Italian health workers. “They didn’t like it,” said Francesca Liotta, the director of Santa Maria degli Ungheresi hospital. But that changed once the Cuban medics learned the Italian language and got to know their colleagues, bringing a fresh wave of energy to the hospital team. “They have the kind of enthusiasm I remember having when I started my career,” said Liotta, who is close to retiring. “I always say this: they are giving us oxygen.” The Guardian visited Polistena after a holiday weekend during which the hospital, a building in desperate need of modernisation, was busy dealing with emergency operations after an increase in road accidents. Internet problems were also causing delays in registering patients. “It’s relentless,” said Liotta. “You fix one problem, and then something else breaks.” This is Fonseca’s first mission in Europe. A surgeon with 10 years’ experience, he has been dispatched on postings around the globe, including two years in Mauritania. The overseas brigades generate huge revenues for Cuba’s communist government, making it a crucial economic lifeline for the country. The missions are also a way of increasing Havana’s soft power. However, Fonseca rejects critics who say health workers are being exploited in order to fill the regime’s coffers. “This is a total lie,” he said. “There is no obligation for us to do this. We are here because we want to be here. We also learn from the experiences. It is a two-way exchange.” To date, the initiative in Calabria has proven to be so effective that it has been extended until at least 2025. Eduardo Gongora, 36, works in the emergency unit and has just signed a new one-year contract. “The most satisfying thing is working alongside our Calabrian colleagues. They have a similar warmth to Cubans and have been very welcoming,” he said. The medics from Cuba have similarly been embraced by residents in Polistena, using downtime to go to the gym, trek in the mountains or let off steam in the karaoke bar. “Some of us do enjoy a little singing,” said Saidy Gallegos Pérez, a physiatrist (rehabilitation medicine) who has opted to spend another year in the town. Roberto Occhiuto, the rightwing president of the Calabrian region, was criticised when he first broached the idea of calling in Cuban reinforcements. “But the experiment has been positive,” he said. “It’s not me saying it, but the Italian doctors who are working with Cubans, and the Calabrian patients. “I knew that Cuban medicine was one of the best in the world and today the same people who criticised me are clamouring for more Caribbean medicine.” But for Liotta, who still frets over being able to fill the hospital shift schedule with an adequate number of staff, a longer-term cure is needed. “There are just not enough people going into the public system,” she said. “I look at the young ones, and they are well prepared, but exhausted. The Cubans have helped revive the team spirit, but I worry about what will happen after 2025.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/16/italy-calabria-cuban-doctors-public-health-system

|