Opinion | Joe Biden: My Plan to Extend Medicare for Another Generation

Millions of Americans work their whole life, paying into Medicare with every working day — starting with their first job, even as teenagers. Medicare is more than a government program. It’s the rock-solid guarantee that Americans have counted on to be there for them when they retire.

For decades, I’ve listened to my Republican friends claim that the only way to be serious about preserving Medicare is to cut benefits, including by making it a voucher program worth less and less every year. Some have threatened our economy unless I agree to benefit cuts.

Only in Washington can people claim that they are saving something by destroying it.

The budget I am releasing this week will make the Medicare trust fund solvent beyond 2050 without cutting a penny in benefits. In fact, we can get better value, making sure Americans receive better care for the money they pay into Medicare.

The two biggest health reform bills since the creation of Medicare, both of which will save Medicare hundreds of billions over the decades to come, were signed by President Barack Obama and me.

The Affordable Care Act embraced smart reforms to make our health care system more efficient while improving Medicare coverage for seniors. The Inflation Reduction Act ended the absurd ban on Medicare negotiating lower drug prices, required drug companies to pay rebates to Medicare if they increase prices faster than inflation and capped seniors’ total prescription drug costs — saving seniors up to thousands of dollars a year. These negotiations, combined with the law’s rebates for excessive price hikes, will reduce the deficit by $159 billion.

We have seen a significant slowdown in the growth of health care spending since the Affordable Care Act was passed. In the decade after the A.C.A., Medicare actually spent about $1 trillion less than the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projected before the A.C.A. reforms were in place. In 2009, before the A.C.A., the Medicare trustees projected that Medicare’s trust fund would be exhausted in 2017; their latest projection is 2028. But we should do better than that and extend Medicare’s solvency beyond 2050.

So first, let’s expand on that progress. My budget will build on drug price reforms by strengthening Medicare’s newly established negotiation power, allowing Medicare to negotiate prices for more drugs and bringing drugs into negotiation sooner after they launch. That’s another $200 billion in deficit reduction. We will then take those savings and put them directly into the Medicare trust fund. Lowering drug prices while extending Medicare’s solvency sure makes a lot more sense than cutting benefits.

Second, let’s ask the wealthiest to pay just a little bit more of their fair share, to strengthen Medicare for everyone over the long term. My budget proposes to increase the Medicare tax rate on earned and unearned income above $400,000 to 5 percent from 3.8 percent. As I proposed in the past, my budget will also ensure that the tax that supports Medicare can’t be avoided altogether. This modest increase in Medicare contributions from those with the highest incomes will help keep the Medicare program strong for decades to come. My budget will make sure the money goes directly into the Medicare trust fund, protecting taxpayers’ investment and the future of the program.

When Medicare was passed, the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans didn’t have more than five times the wealth of the bottom 50 percent combined, and it only makes sense that some adjustments be made to reflect that reality today.

Let’s ask them to pay their fair share so that the millions of workers who helped them build that wealth can retire with dignity and the Medicare they paid into. Republican plans that protect billionaires from a penny more in taxes — but won’t protect a retired firefighter’s hard-earned Medicare benefits — are just detached from the reality that hardworking families live with every day.

Add all that up, and my budget will extend the Medicare trust fund for more than another generation, an additional 25 years or more of solvency — beyond 2050. These are common-sense changes that I’m confident an overwhelming majority of Americans support.

MAGA Republicans have a different view. They want to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act. That means they want to take away the power we just gave to Medicare to negotiate for lower prescription drug prices. Get rid of the $35 per month cap for insulin we just got for people on Medicare. And remove the current $2,000 total annual cap for seniors.

If the MAGA Republicans get their way, seniors will pay higher out-of-pocket costs on prescription drugs and insulin, the deficit will be bigger, and Medicare will be weaker. The only winner under their plan will be Big Pharma. That’s not how we extend Medicare’s life for another generation or grow the economy.

This week, I’ll show Americans my full budget vision to invest in America, lower costs, grow the economy and not raise taxes on anyone making under $400,000. I urge my Republican friends in Congress to do the same — and show the American people what they value.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/07/opinion/joe-biden-medicare.html

Opinion The GOP’s epic defeat on health care is laid bare in North Carolina

But in the near-decade since, health-care advocates have painstakingly overcome that opposition, and many of those states have now embraced the expansion. Between this and the failure of years of ACA repeal drives, the GOP has essentially been routed in the Obamacare wars.

The scale of this defeat is evident in big news out of North Carolina, where leaders in the GOP-controlled legislature announced a deal Thursday to accept the expansion. It will require hospitals to pay the state’s minimal contribution to the cost. (The federal government generally funds 90 percent.)

Republicans accepted this deal only after years of ferocious resistance. And this is a tremendous win for advocates and Democrats, because it stands to cover as many as 600,000 poor North Carolinians, in a state that proponents have targeted for years.

The popularity of Medicaid appears to have surprised conservatives, who apparently saw it as an easily targeted big-government program for poor people. The prospect of cuts to Medicare — whose beneficiaries are vocal, organized seniors — presented a well-understood danger. But surely Medicaid cuts wouldn’t matter as much politically.

Reality has shown otherwise. In the past dozen years or so, voters in seven GOP-run or red-leaning holdout states have defied Republican legislatures by voting in referendums to accept the expansion. In a number of others, Republican officials have initiated acceptance through executive actions or legislation. If North Carolina’s legislature passes the new deal, only 10 holdout states will remain.

What’s more, when congressional Republicans tried to repeal the ACA in 2017, which would have taken Medicaid coverage from millions more Americans, they faced an unexpectedly furious public backlash and backed down despite controlling all of Washington.

Today, a remarkable 91.7 million Americans are on Medicaid and its children’s subsidiary, CHIP — more than a quarter of the country’s population. Republicans can’t ignore that any longer.

All of this is creating a strange divide in the GOP between state and national lawmakers.

On the state level, it’s becoming clearer that resisting the expansion is politically untenable, particularly in purplish states. In North Carolina, for instance, the expansion has had overwhelming public support. When the state Senate leader finally accepted the expansion in principle last year, he openly admitted he had fought it long and hard before capitulating to its fundamental financial logic.

“Most red states have come around to the view that the federal money on the table for their low-income residents is too hard to turn your back on,” Larry Levitt, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s executive vice president for health policy, tells us.

Yet back in Washington, congressional Republicans are still looking to cut Medicaid. Some are mulling a plan to cut $2 trillion from Medicaid. And a bloc of 173 House conservatives has proposed to convert Medicaid and CHIP to block grants and reduce their funding by $3.6 trillion over 10 years.

But if an anti-Medicaid stance is becoming untenable in even somewhat red-leaning places — such as North Carolina — it seems likely to hurt broader GOP prospects as a national party position.

Consider what could happen in 2024. As USA Today columnist Jill Lawrence details, most of the main GOP presidential contenders, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley, either opposed the expansion in their states or fought for ACA repeal.

The eventual GOP nominee will surely want to keep the debate over the ACA as abstract as possible. He or she will likely rail that “Obamacare” represents Big Bad Government in some undefined sense while vaguely committing to repeal to keep the base and conservative thought leaders happy.

But the Medicaid expansion in places such as North Carolina will make the stakes a lot more concrete. The repeal vow will threaten the coverage of hundreds of thousands in that state. The expansion would deliver a big lift to struggling rural hospitals there, as it has in other expansion states. These gains will also be threatened.

All of that won’t be easy for the GOP nominee to navigate in a state that Republicans have been winning lately, but only by very slim margins.

True, the battle is far from entirely won. Enormous populations of Medicaid-eligible uninsured people still remain in big GOP-controlled states such as Florida, Texas and Georgia, with no hope of an expansion anytime soon.

But now, if North Carolina’s expansion goes through, only a fraction of the original holdout states will remain, most with relatively small populations. If you had predicted all this a decade ago, it would have seemed impossibly optimistic and naive.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/03/03/republican-defeat-medicaid-north-carolina/

Millions who rely on Medicaid may be booted from program

As states begin checking eligibility for Medicaid for the first time in three years, as many as 14 million people could lose access.

by Erica Nitschke - Portland Press Herald - February 27, 2023

WASHINGTON — If you get health care coverage through Medicaid, you might be at risk of losing that coverage over the next year.

Roughly 84 million people are covered by the government-sponsored program, which has grown by 20 million people since January 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

But as states begin checking everyone’s eligibility for Medicaid for the first time in three years, as many as 14 million people could lose access to that health care coverage.

A look at why so many people may no longer qualify for the Medicaid program over the next year and what you need to know if you’re one of those people who relies on the program.

WHAT’S HAPPENING TO MEDICAID?

At the beginning of the pandemic, the federal government prohibited states from kicking people off Medicaid, even if they were no longer eligible. Before the pandemic, people would regularly lose their Medicaid coverage if they started making too much money to qualify for the program, gained health care coverage through their employer or moved into a new state.

That all stopped once COVID-19 started spreading across the country.

Over the next year, states will be required to start checking the eligibility again of every person who is on Medicaid. People will have to fill out forms to verify their personal information, including address, income and household size.

WHEN MIGHT I LOSE MY COVERAGE?

That will vary depending on which state you live in; some states are moving faster than others to check eligibility. Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Iowa, New Hampshire, Ohio, Oklahoma and West Virginia are among the states that will begin removing ineligible Medicaid recipients as early as April.

Other states will start taking that step in May, June or July.

Not everyone will be removed from the program all at once. States plan to verify all recipients’ eligibility over periods of nine months to one year.

HOW WILL I BE NOTIFIED IF I’M LOSING COVERAGE?

If you rely on Medicaid for care, it’s important to update your contact information, including home address, phone number and email with the state from which you receive benefits.

States will mail a renewal form to your home. The federal government also requires states to contact you in another way -– by phone, text message or email –- to remind you to fill out the form.

Even if mailed notices reach the right address, they can be set aside and forgotten, said Kate McEvoy, executive director of the nonprofit National Association of Medicaid Directors.

“A text might just grab someone’s attention in a way that would be more accessible,” she said, noting that a quick message also may be less intimidating than a mailed notice.

Most states have already used texting for things such as reminding patients to get a COVID-19 vaccine or about upcoming doctor’s visits. But sending mass texts on Medicaid eligibility will be new, McEvoy said.

You will have at least 30 days to fill out the form. If you do not fill out the form, states will be able to remove you from Medicaid.

WHAT ARE MY OPTIONS IF I’M KICKED OFF MEDICAID?

Many people who will no longer qualify for Medicaid coverage can turn to the Affordable Care Act’s marketplace for coverage, where they’ll find health care coverage options that may cost less than $10 a month.

But the coverage available on the marketplace will still be vastly different from what’s offered through Medicaid. Out-of-pocket expenses and co-pays are often higher. Also, people will need to check if the insurance plans offered through the marketplace will still cover their doctors.

A special enrollment period will open for people who are unenrolled from Medicaid that will start on March 31 and last through July 31, 2024. People who lose Medicaid coverage will have up to 60 days to enroll after losing coverage, according to guidance the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services sent to states last month.

MY CHILDREN ARE ENROLLED IN MEDICAID. WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO THEIR COVERAGE?

More than half of U.S. children receive health care coverage through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Even if you receive a notice that you’re no longer eligible for Medicaid, it’s likely that your child still qualifies for the program or for health care coverage through CHIP, which covers children whose families make too much money qualify for Medicaid but don’t earn enough to afford private health insurance.

Between 80% and 90% percent of children will still be eligible for those programs, according to estimates from the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute’s Center for Children and Families.

“When a parent receives a message that they aren’t eligible anymore, they often assume their child is no longer eligible either,” said Joan Alker, the center’s executive director. “It’s more common to find that the parent is no longer eligible for Medicaid, but the child still is.”

https://www.pressherald.com/2023/02/26/millions-who-rely-on-medicaid-may-be-booted-from-program/ by

They could lose the house — to Medicaid

by Tony Leys - Kaiser Health News - March 1, 2023

PERRY, Iowa — Fran Ruhl's family received a startling letter from the Iowa Department of Human Services four weeks after she died in January 2022.

"Dear FAMILY OF FRANCES RUHL," the letter begins. "We have been informed of the death of the above person, and we wish to express our sincere condolences."

The letter gets right to the point: Iowa's Medicaid program had spent $226,611.35 for Ruhl's health care, and the government was entitled to recoup that money from her estate, including nearly any assets she owned or had a share in. If a spouse or disabled child survived Ruhl, the collection could be delayed until after their death, but the money would still be owed.

The notice said the family had 30 days to respond.

"I said, 'What is this letter for? What is this?'" says Ruhl's daughter, Jen Coghlan.

It seemed bogus, but it was real. Federal law requires all states to have "estate recovery programs," which seek reimbursements for spending under Medicaid, the joint federal and state health insurance program mainly for people with low incomes or disabilities. The recovery efforts collect more than $700 million a year, according to a 2021 report from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, or MACPAC, an agency that advises Congress.

tates have leeway to decide whom to bill and what type of assets to target. Some states collect very little. For example, Hawaii's Medicaid estate recovery program collected just $31,000 in 2019, according to the federal report.

Iowa, whose population is about twice Hawaii's, recovered more than $26 million that year, the report says.

Iowa uses a private contractor to recoup money spent on Medicaid coverage for any participant who was 55 or older or was a resident of a long-term care facility when they died. Even if an Iowan used few health services, the government can bill their estate for what Medicaid spent on premiums for coverage from private insurers known as managed-care organizations.

Supporters say the clawback efforts help ensure people with significant wealth don't take advantage of Medicaid, a program that spends more than $700 billion a year nationally.

Critics say families with resources, including lawyers, often find ways to shield their assets years ahead of time — leaving other families to bear the brunt of estate recoveries. For many, the family home is the most valuable asset, and heirs wind up selling it to settle the Medicaid bill.

For the Ruhl family, that would be an 832-square-foot, steel-sided house that Fran Ruhl and her husband, Henry, bought in 1964. It's in a modest neighborhood in Perry, a central Iowa town of 8,000 people. The county tax assessor estimates it's worth $81,470.

Henry Ruhl, 83, wanted to leave the house to Coghlan, but since his wife was a joint owner, the Medicaid recovery program could claim half the value after his death.

Fran Ruhl, a retired child care worker, was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia, a debilitating brain disorder. Instead of placing her in a nursing home, the family cared for her at home. A case manager from the Area Agency on Aging suggested in 2014 they look into the state's "Elderly Waiver" program to help pay expenses that weren't covered by Medicare and Tricare, the military insurance Henry Ruhl earned during his Iowa National Guard career.

oghlan still has paperwork the family filled out. The form says the application was for people who wanted to get "Title 19 or Medicaid," but then listed "other programs within the Medical Assistance Program," including Elderly Waiver, which the form explains "helps keep people at home and not in a nursing home."

Coghlan says the family didn't realize the program was an offshoot of Medicaid, and the paperwork in her file did not clearly explain the government might seek reimbursement for properly paid benefits.

Some of the Medicaid money went to Coghlan for helping care for her mother. She paid income taxes on those wages, and she says she likely would have declined to accept the money if she'd known the government would try to scoop it back after her mother died.

Iowa Medicaid Director Elizabeth Matney says that in recent years the state added clearer notices about the estate recovery program on forms people fill out when they apply for coverage.

"We do not like families or members being caught off guard," she said in an interview. "I have a lot of sympathy for those people."

Matney says her agency has considered changes to the estate recovery program, and she would not object if the federal government limited the practice. Iowa's Medicaid estate collections topped $30 million in fiscal year 2022, but that represented a sliver of Medicaid spending in Iowa, which is over $6 billion a year. And more than half the money recouped goes back to the federal government, she said.

Matney notes families can apply for "hardship exemptions" to reduce or delay recovery of money from estates. For example, she said, "if doing any type of estate recovery would deny a family of basic necessities, like food, clothing, shelter, or medical care, we think about that."Sumo Group, a private company that runs Iowa's estate recovery program, reported that 40 hardship requests were granted in fiscal 2022, and 15 were denied. The Des Moines company reported collecting money from 3,893 estates that year. Its director, Ben Chatman, declined to comment to KHN. Sumo Group is a subcontractor of a national company, Health Management Systems, which oversees Medicaid estate recoveries in several states. The national company declined to identify which states it serves or discuss its methods. Iowa pays the companies 11% of the proceeds from their estate recovery collections.

The 2021 federal advisory report urged Congress to bar states from collecting from families with meager assets, and to let states opt out of the effort altogether. "The program mainly recovers from estates of modest size, suggesting that individuals with greater means find ways to circumvent estate recovery and raising concerns about equity," the report says.

U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky introduced a bill in 2022 that would end the programs.

The Illinois Democrat says many families are caught unawares by Medicaid estate recovery notices. Their loved ones qualified for Medicaid participation, not realizing it would wind up costing their families later. "It's really a devastating outcome in many cases," she said.

Schakowsky noted some states have tried to avoid the practice. West Virginia sued the federal government in an attempt to overturn the requirement that it collect against Medicaid recipients' estates. That challenge failed.

Schakowsky's bill had no Republican co-sponsors and did not make it out of committee. But she hopes the proposal can move ahead, since every member of Congress has constituents who could be affected: "I think this is the beginning of a very worthy and doable fight."

States can limit their collection practices. For example, Massachusetts implemented changes in 2021 to exempt estates of $25,000 or less. That alone was expected to slash by half the number of targeted estates.

Massachusetts also made other changes, including allowing heirs to keep at least $50,000 of their inheritance if their incomes are less than 400% of the 2022 federal poverty level, or about $54,000 for a single person.

Prior to the changes, Massachusetts reported more than $83 million in Medicaid estate recoveries in 2019, more than any other state, according to the MACPAC report.

Supporters of estate recovery programs say they provide an important safeguard against misuse of Medicaid.

Mark Warshawsky, an economist for the conservative American Enterprise Institute, argues that other states should follow Iowa's lead in aggressively recouping money from estates.

Warshawsky says many other states exclude assets that should be fair game for recovery, including tax-exempt retirement accounts, such as 401(k)s. Those accounts make up the bulk of many seniors' assets, he said, and people should tap the balances to pay for health care before leaning on Medicaid.

Warshawsky says Medicaid is intended as a safety net for Americans who have little money. "It's the absolute essence of the program," he says. "Medicaid is welfare."

People should not be able to shelter their wealth to qualify, he says. Instead, they should be encouraged to save for the possibility they'll need long-term care, or to buy insurance to help cover the costs. Such insurance can be expensive and contain caveats that leave consumers unprotected, so most people decline to buy it. Warshawsky says that's probably because people figure Medicaid will bail them out if need be.

Eric Einhart, a New York lawyer and board member of the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys, says Medicaid is the only major government program that seeks reimbursement from estates for properly paid benefits.

Medicare, the giant federal health program for seniors, covers virtually everyone 65 or older, no matter how much money they have. It does not seek repayments from estates.

"There's a discrimination against what I call 'the wrong type of disease,'" Einhart says. Medicare could spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on hospital treatment for a person with serious heart problems or cancer, and no government representatives would try to recoup the money from the person's estate. But people with other conditions, such as dementia, often need extended nursing home care, which Medicare won't cover. Many such patients wind up on Medicaid, and their estates are billed.

On a recent afternoon, Henry Ruhl and his daughter sat at his kitchen table in Iowa, going over the paperwork and wondering how it would all turn out.

The family found some comfort in learning that the bill for Fran Ruhl's Medicaid expenses will be deferred as long as her husband is alive. He won't be kicked out of his house. And he knows his wife's half of their assets won't add up to anything near the $226,611.35 the government says it spent on her care.

"You can't get — how do you say it?" he asks.

"Blood from a turnip," his daughter replies.

"That's right," he says with a chuckle. "Blood from a turnip."

Consolidations and profiteering: the relentless rise of hospital expenditures

by Peter Arno - Health Care Un-Covered - March 2, 2023

What is driving hospital expenditures higher and higher?

Amidst all the talk of rising health-care costs and profiteering by drug and insurance companies, particularly managed-care firms, the hospital industry remains relatively unexamined by the mainstream media.

This has finally begun to change with recent news of hospital closures, garnishing wages and foisting debt collectors on non-paying patients. But overall, hospitals — which comprise the single largest component of health-care expenditures in the country, accounting for one out of every three health-care dollars — remain relatively unscathed by public opinion.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which track annual health-care costs and project them into the future, reported that hospital expenditures were $1.2 trillion in 2019 and will reach $2.2 trillion in 2030. But if hospital expenditures were to grow at the same rate as the economy (GDP) during this time period, the total would be nearly $2 trillion ($1.96T) lower between 2019 and 2030 according to CMS’s own estimates.

What is driving hospital expenditures higher and higher? There are many contributing factors. These include the dizzying array of wasteful administrative costs embedded in our multi-payer (and multi-price) insurance system. Studies estimate that administrative costs amount to 15-30% of total health-care spending, and that hospitals in conjunction with our polyglot insurance system account for the bulk of that.

Upcoding diagnoses (adding additional diagnosis codes on patient records to garner higher reimbursement) adds billions to the health-care tab. A recent report by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), an independent advisory agency established by Congress, found that between 2007 and 2023, coding intensity, i.e. upcoding, generated nearly $124 billion in excess payments to Medicare Advantage plans.

Overpriced pharmaceuticals also add to hospitals’ bottom line. A recent study found that hospital prices for the top 37 infused cancer drugs averaged 86.2% higher per unit than in physician offices. However, perhaps the single largest driver of rising expenditures has been hospital consolidation through mergers and acquisitions. By 2018, over 95% of metropolitan areas had highly concentrated hospital markets. Moreover, concentrated markets are associated with higher hospital prices — with price increases often exceeding 20% when mergers occur — despite little evidence of quality improvements.

While we must pay closer attention to hospitals’ role in rising health expenditures, it is the entire health-care system that requires radical transformation because it is working (as designed) to extract private profits (called “surplus'' in the case of nonprofit hospitals). As Don Berwick recently wrote in JAMA, “…kleptocapitalist behaviors that raise prices, salaries, market power, and government payment to extreme levels hurt patients and families, vulnerable institutions, governmental programs, small and large businesses, and workforce morale.”

byBIG INSURANCE 2022: Revenues reached $1.25 trillion thanks to sucking billions out of the pharmacy supply chain – and taxpayers' pockets

Analysis of the 2022 financial statements of UnitedHealth Group, CVS/Aetna, Cigna, Elevance, Humana, Centene, and Molina

by Wendell Potter - HEALTH CARE un-covered - February 27, 2023

HIGHLIGHTS

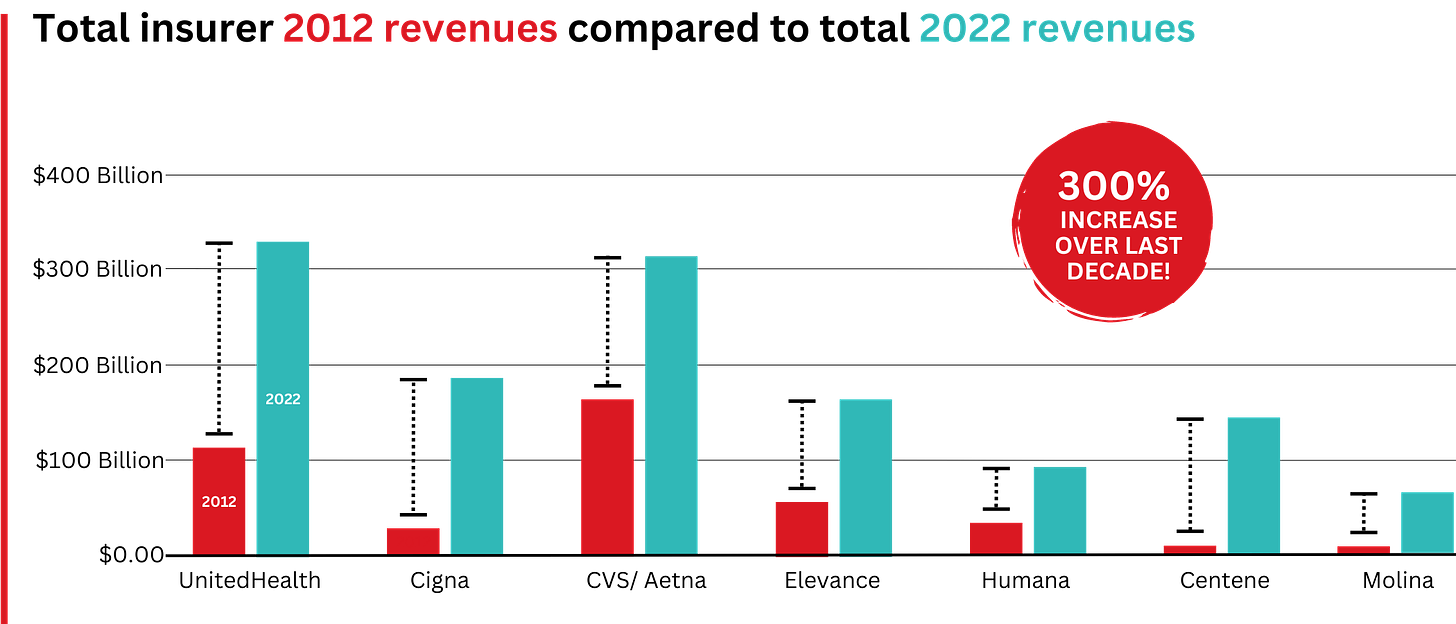

Big Insurance revenues and profits have increased by 300% and 287% respectively since 2012 due to explosive growth in the companies’ pharmacy benefit management (PBM) businesses and the Medicare replacement plans they call Medicare Advantage.

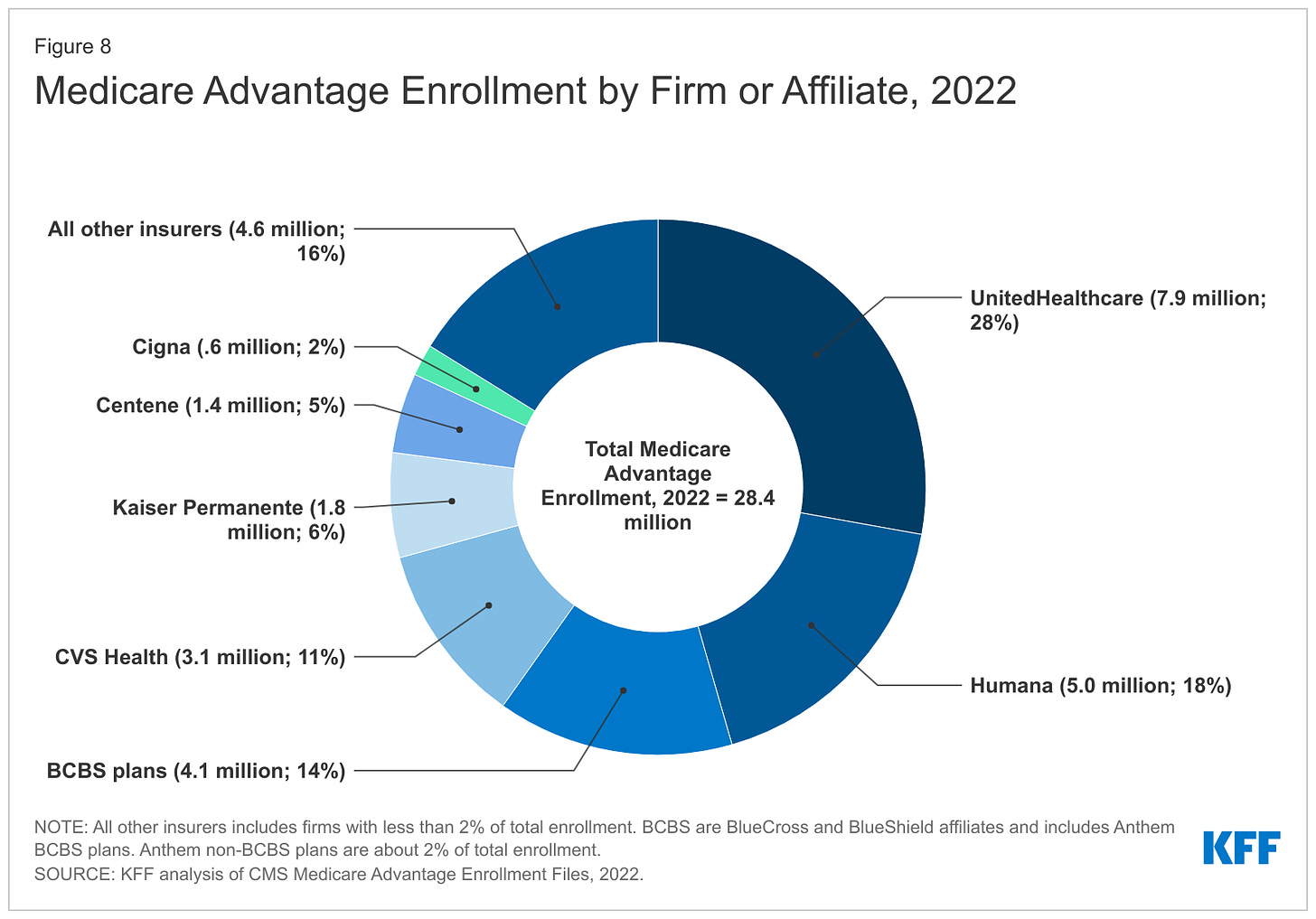

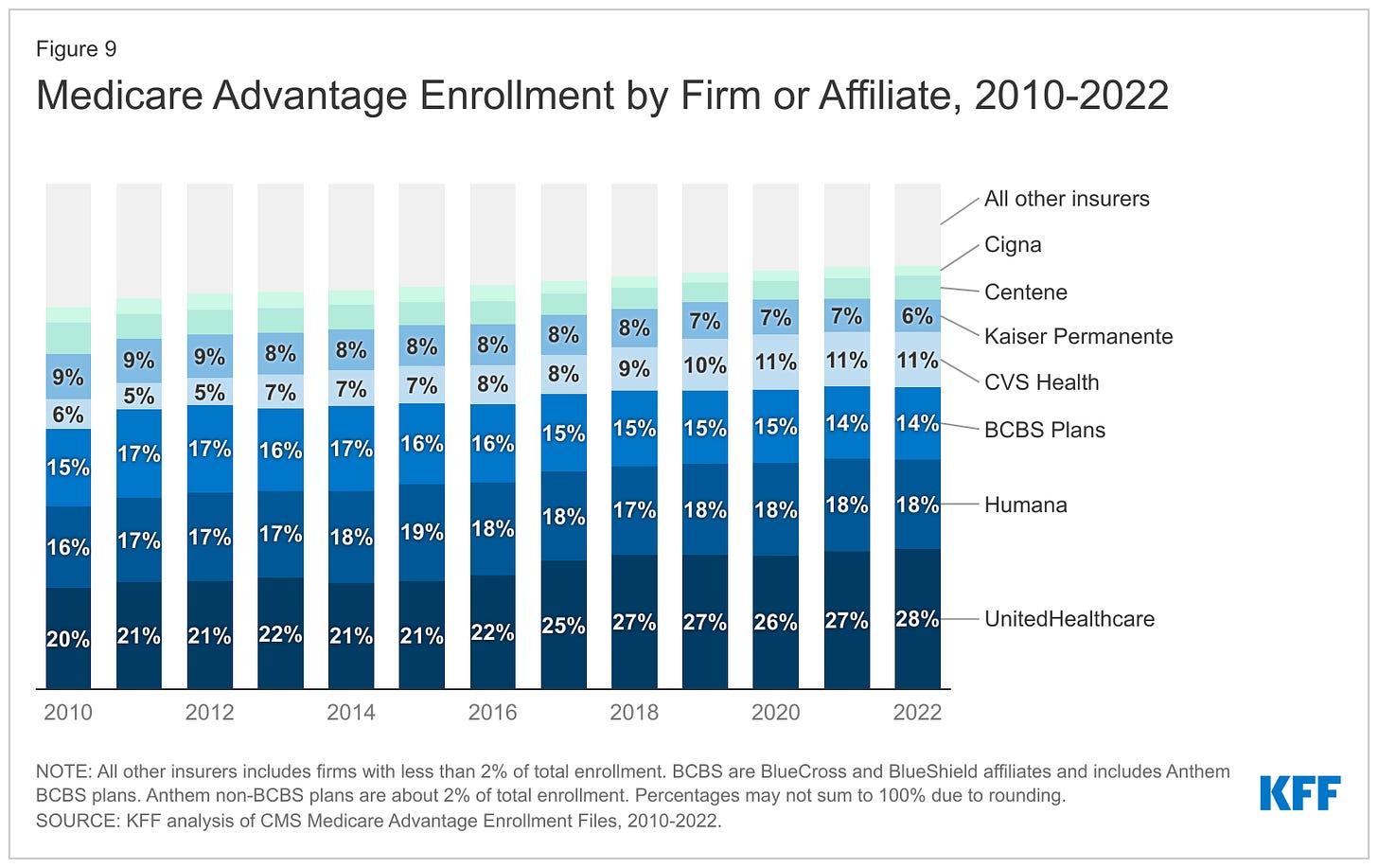

The for-profits now control more than 80% of the national PBM market and more than 70% of the Medicare Advantage market.

In 2022, Big Insurance revenues reached $1.25 trillion and profits soared to $69.3 billion.

That's a 300% increase in revenue and a 287% increase in profits from 2012, when revenue was $412.9 billion and profits were $24 billion.

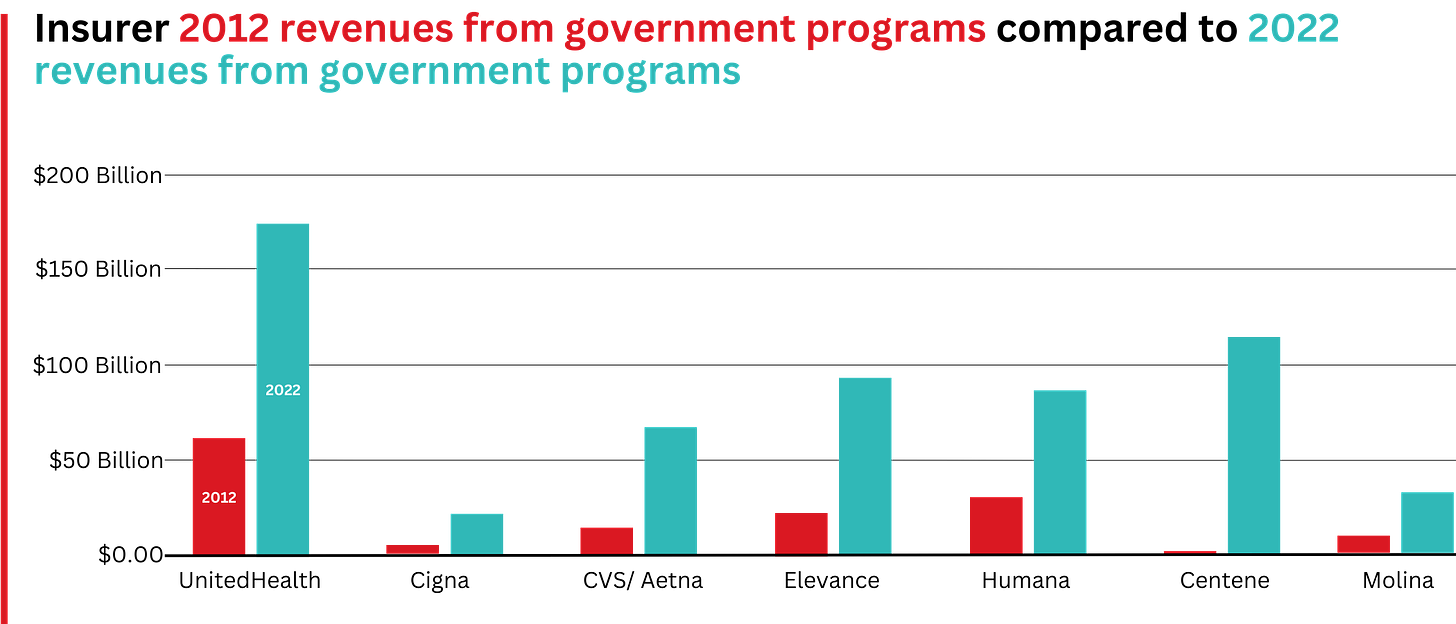

What has changed dramatically over the decade is that the big insurers are now getting far more of their revenues from the pharmaceutical supply chain and from taxpayers as they have moved aggressively into government programs. This is especially true of Humana, Centene, and Molina, which now get, respectively, 85%, 88%, and 94% of their health-plan revenues from government programs.

The two biggest drivers are their fast-growing pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), the relatively new and little-known middleman between patients and pharmaceutical drug manufacturers, and the privately owned and operated Medicare replacement plans they market as Medicare Advantage.

With the exception of Humana, Centene, and Molina, most of the companies that constitute Big Insurance continue to make substantial amounts of money selling policies and services in what they refer to as their commercial businesses – to individuals, families, and employers – but the seven companies’ commercial revenue grew just 260%, or $176 billion, over 10 years (from $110.4 billion to $287.1 billion). While that’s significant, profitable growth in the commercial sector has become a major challenge for big insurers – so much so that Humana just last week announced it is exiting the employer-sponsored health-insurance marketplace entirely.

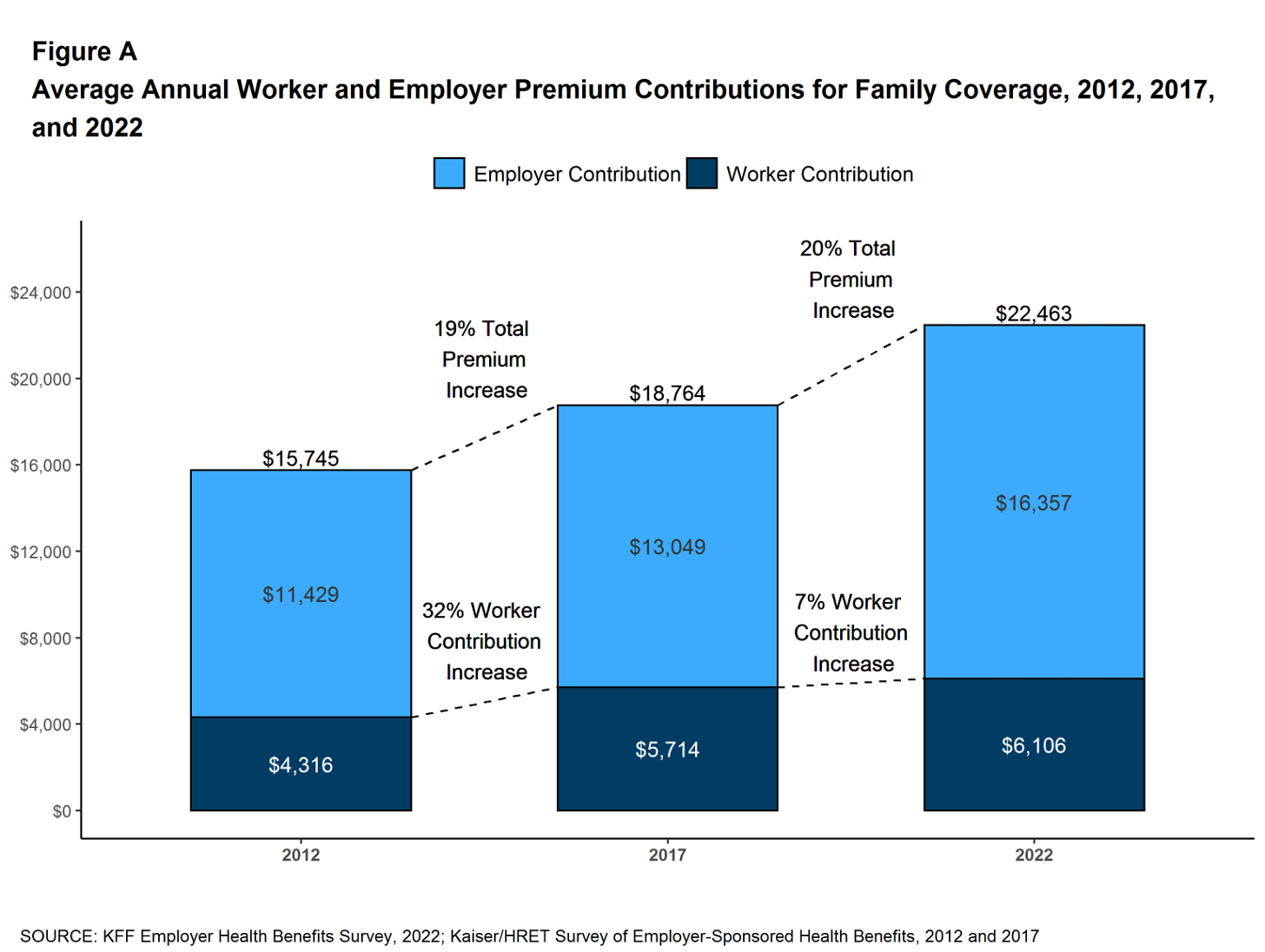

The insurers’ commercial businesses have stagnated because small businesses – which employ nearly half of the nation’s workers – are increasingly being priced out of the health insurance market. Most small businesses can no longer afford the premiums. The average premium for an employer-sponsored family plan – not including out-of-pocket requirements – was $22,463 in 2022, up 43% since 2012, which has contributed to the decades-long decline in the percentage of U.S. employers offering coverage to their workers. The percentage of U.S. employers providing some level of health benefits to their workers dropped from 69% to 51% between 1999 and 2022 – including a dramatic 8% decrease last year alone. Growth in this category is largely the result of insurers “stealing market share” from each other or from smaller competitors. As a consequence of this segment’s relative stagnation, PBMs and government programs have become the new cash cows for Big Insurance.

PBM HIGHLIGHTS

Cigna now gets far more revenue from its PBM than from its health plans. CVS gets more revenue from its PBM than from either Aetna’s health plans or its nearly 10,000 retail stores.

UnitedHealth has the biggest share of both the PBM and Medicare markets and, through numerous acquisitions of physician practices, is now the largest U.S. employer of doctors.

PBMs are middlemen companies that manage prescription drug benefits for health insurers, Medicare Part D drug plans, employers, and, in some cases, unions. As the Commonwealth Fund has noted:

PBMs have a significant behind-the-scenes impact in determining total drug costs for insurers, shaping patients’ access to medications, and determining how much pharmacies are paid.

The Commonwealth Fund went on to say that PBMs have faced growing scrutiny about their role in rising prescription drug costs and spending. A big reason for the scrutiny – by Congress, state lawmakers and now also by the FTC – is that the biggest PBMs are now owned by Big Insurance. Through mergers and acquisitions in recent years, three of the seven for-profit insurers – Cigna, CVS/Aetna, and UnitedHealth – now control 80% of the U.S. pharmacy benefits market. They determine which drugs will be listed in each of their formularies (lists of drugs they will “cover” based on secret deals they negotiate with pharmaceutical companies) and how much patients will have to pay out of their own pockets at the pharmacy counter – in many cases hundreds or thousands of dollars – before their coverage kicks in. The PBMs also “steer” health-plan enrollees to their preferred or owned pharmacies (and, increasingly, away from independent pharmacists), thereby capturing even more of what we spend on our prescription medications.

Ten years ago, PBMs contributed relatively little to the three companies’ revenues and profits. But since then, the rapid growth of PBMs has transformed all of the companies. The combined revenues from their PBM business units increased 250% between 2012 and 2022, from $196.7 billion to $492.4 billion.

The PBM profit growth at the three companies over the past decade was even more dramatic than revenue growth. Collectively, their PBM profits increased 438%, from $6.3 billion in 2012 to $27.6 billion in 2022.

As a result of this fast growth, more than half (52%) of three companies’ profits in 2022 came from their PBM business units: Cigna’s Evernorth, CVS/Aetna’s Caremark, and UnitedHealth’s Optum. Cigna now gets far more revenue and profits from its PBM than from its health plans. And CVS gets more revenue from its PBM than from either Aetna’s health plans or its nearly 10,000 retail stores. (The companies’ business units that include their PBMs have also moved aggressively in recent years into health-care delivery through acquisitions of physician practices, clinics, dialysis centers, and other facilities. Notably, UnitedHealth Group is now the largest U.S. employer of physicians.)

GOVERNMENT PROGRAMS HIGHLIGHTS

More than 90% of health-plan revenues at three of the companies come from government programs as they continue to privatize both Medicare and Medicaid, through Medicare Advantage in particular.

Enrollment in government-funded programs increased by 261% in 10 years; by contrast commercial enrollment increased by just 10% over the past decade.

Commercial enrollment actually declined at both UnitedHealth and Humana.

85% of Humana’s health-plan members are in government-funded programs; at Centene, it is 88%, and at Molina, it is 94%.

The big insurers now manage most states’ Medicaid programs – and make billions of dollars for shareholders doing so – but most of the insurers have found that selling their privately operated Medicare replacement plans is even more financially rewarding for their shareholders.

This is especially apparent when you see that the Big Seven’s combined revenues from taxpayer-supported programs grew 500%, from $116.3 billion in 2012 to $577 billion in 2022.

These numbers should be of interest to the Biden administration and members of Congress, many of whom are calling for much greater scrutiny of the Medicare Advantage program. Numerous media and government reports have shown that the federal government is overpaying private insurers billions of dollars a year, largely because of loopholes in laws and regulations that enable them to get more taxpayer dollars by claiming their enrollees are sicker than they really are. The companies also make aggressive use of prior authorization, largely unknown in traditional Medicare, to avoid paying for doctor-ordered care and medications.

In addition to their focus on Medicare and Medicaid, the companies also profit from the generous subsidies the government pays insurers to reduce the premiums they charge individuals and families who do not qualify for either Medicare or Medicaid or who work for an employer that does not offer subsidized coverage. But many people enrolled in those types of plans – primarily through the health insurance “marketplaces” established by the Affordable Care Act – cannot afford the deductibles and other out-of-pocket requirements they must pay before their insurers will begin paying their medical claims.

Changes in health-plan enrollment over the past decade show how dramatic this shift has been. Between 2012 and 2022, enrollment in the companies’ private commercial plans increased by 10%, from 85.1 million in 2012 to 93.8 million in 2022.

By comparison, growth in enrollment in taxpayer-supported government programs increased 261%, from 27 million in 2012 to 70.4 million in 2022.

Within that category, Medicare Advantage enrollment among the Big Seven increased 252%, from 7.8 million in 2012 to 19.7 million in 2022.

Nationwide, enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans increased to 28.4 million in 2022 (and to 30 million this year). That means that the Big Seven for-profit companies control more than 70% of the Medicare Advantage market.

The remaining growth in the government segment occurred in the Medicaid programs that a subset of the Big Seven (UnitedHealth, Elevance, Centene, and Molina in particular) manages for several states.

27.5 million people remain uninsured in the United States. Up to 14 million more will lose their Medicaid coverage once the pandemic emergency period ends later this year.

100 million of us – almost one of every three people in this country – now have medical debt.

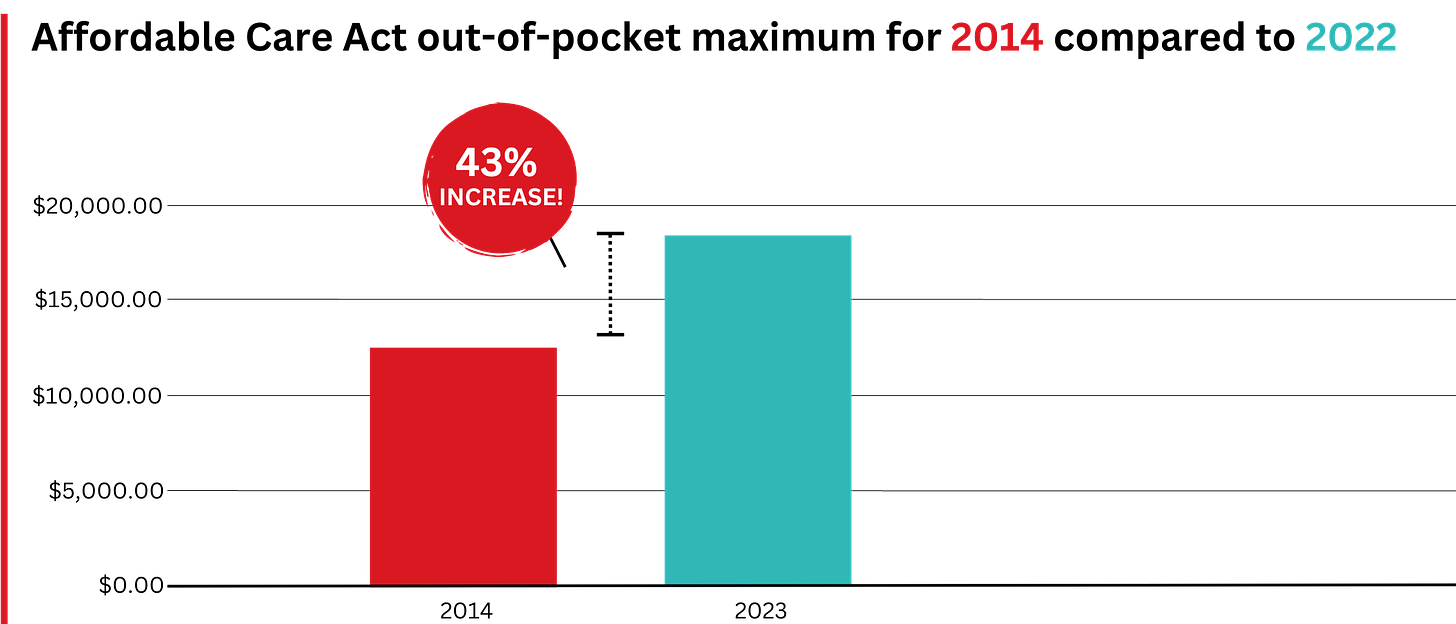

In 2023, U.S. families can be on the hook for up to $18,200 in out-of-pocket requirements before their coverage kicks in, up 43% since 2014 when it was $12,700.

44% of people in the United States who purchased coverage through the individual market and (ACA) marketplaces were underinsured or functionally uninsured.

46% of those surveyed said they had skipped or delayed care because of the cost.

42% said they had problems paying medical bills or were paying off medical debt.

Half (49%) said they would be unable to pay an unexpected medical bill within 30 days, including 68% of adults with low income, 69% of Black adults, and 63% of Latino/Hispanic adults.

In 2021, about $650 million, or about one-third of all funds raised by GoFundMe, went to medical campaigns. That’s not surprising when you realize that in the United States, even people with insurance all too often feel they have no choice but to beg for money from strangers to get the care they or a loved one needs.

62% of bankruptcies are related to medical costs.

Even as we spend about $4.5 trillion on health care a year, Americans are now dying younger than people in other wealthy countries. Life expectancy in the United States actually decreased by 2.8 years between 2014 and 2021, erasing all gains since 1996, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

BOTTOM LINE: The companies that comprise Big Insurance are vastly different from what they were just 10 years ago, but policymakers, regulators, employers, and the media have so far shown scant interest in putting their business practices under the microscope. Changes in federal law, including the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, which created the lucrative Medicare Advantage market, and the Affordable Care Act of 2010, which gave insurers the green light to increase out-of-pocket requirements annually and restrict access to care in other ways, opened the Treasury and Medicare Trust Fund to Big Insurance. In addition, regulators have allowed almost all of their proposed acquisitions to go forward, which has created the behemoths they are today. CVS/Health is now the 4th largest company on the Fortune 500 list of American companies. UnitedHealth Group is now No. 5 – and all the others are climbing toward the top 10.

d to Email AlertsDr. Arthur Smolensky, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity's intrusion into ERs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ER patients were seen in ERs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ER has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ER on their own, he said.

"Most of us didn't go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are," Smolensky said. "We want to take care of patients."

"I Guess We're the First Guinea Pigs for Our ER"

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ER where Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor's supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

"I guess we're the first guinea pigs for our ER," he said. "If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there's only one doctor there. … We need to be prepared."

Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master's degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ER visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in ERs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged ERs to employ "the least expensive resource" and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision's website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a "concept guide" that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company's profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

Two firms dominate the ER staffing industry: TeamHealth, bought by private equity firm Blackstone in 2016, and Envision Healthcare, bought by KKR in 2018. Trying to undercut these staffing giants is American Physician Partners, a rapidly expanding company that runs ERs in at least 17 states and is 50% owned by private equity firm BBH Capital Partners.

These staffing companies have been among the most aggressive in replacing doctors to cut costs, said Dr. Robert McNamara, a founder of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University.

"It's a relatively simple equation," McNamara said. "Their No. 1 expense is the board-certified emergency physician. So they are going to want to keep that expense as low as possible."

Not everyone sees the trend of private equity in ER staffing in a negative light. Jennifer Orozco, president of the American Academy of Physician Associates, which represents physician assistants, said even if the change — to use more nonphysician providers — is driven by the staffing firms' desire to make more money, patients are still well served by a team approach that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

"Though I see that shift, it's not about profits at the end of the day," Orozco said. "It's about the patient."

The "shift" is nearly invisible to patients because hospitals rarely promote branding from their ER staffing firms and there is little public documentation of private equity investments.

Dr. Arthur Smolensky, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity's intrusion into ERs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ER patients were seen in ERs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ER has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ER on their own, he said.

"Most of us didn't go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are," Smolensky said. "We want to take care of patients."

"I Guess We're the First Guinea Pigs for Our ER"

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ER where Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor's supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

"I guess we're the first guinea pigs for our ER," he said. "If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there's only one doctor there. … We need to be prepared."

Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master's degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ER visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in ERs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged ERs to employ "the least expensive resource" and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision's website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a "concept guide" that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company's profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

Medical debt affects millions, and advocates push IRS, consumer agency for relief

Dozens of advocates for patients and consumers, citing widespread harm caused by medical debt, are pushing the Biden administration to take more aggressive steps to protect Americans from medical bills and debt collectors.

In letters to the IRS and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the groups call for new federal rules that among other things would prohibit debt for medically necessary care from appearing on consumer credit reports.

Advocates also want the federal government to bar nonprofit hospitals from selling patient debt or denying medical care to people with past-due bills, practices that remain widespread across the U.S., KHN found.

And the groups are pressing the IRS to crack down on nonprofit hospital systems that withhold financial assistance from low-income patients or make aid cumbersome to get, another common obstacle KHN documented.

"Every day people are having to make choices about housing and clothing and food because of medical debt," says Emily Stewart, executive director of Community Catalyst, a Boston nonprofit leading the effort. "It's really urgent the Biden administration take action to put protections in place."

Among the more than 50 groups supporting the initiative are national advocates such as the National Consumer Law Center, the Arthritis Foundation, and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Nationwide, 100 million people have health care debt, according to a KHN-NPR investigation, which has documented a crisis that is driving Americans from their homes, draining their savings, and preventing millions from accessing care they need.

While some of the debt appears on credit reports, much of it is hidden elsewhere as credit card balances, loans from relatives, or payment plans to hospitals and other medical providers.

The scale of this problem and its toll have spurred several national and state efforts.

Last spring, the White House directed federal agencies to work on relieving medical debts for veterans and to stop considering medical debt in evaluating eligibility for some federally backed mortgages.

California, Colorado, Maryland, New York, and other states have enacted new laws to expand consumer protections and require hospitals within their borders to increase financial aid. And the three largest credit agencies — Equifax, Experian, and Transunion — said they would stop including some medical debt on credit reports as of last July.

But many consumer and patient advocates say the actions, while important, still leave millions of Americans vulnerable to financial ruin if they become ill or injured. "It is critical that the CFPB take additional action," the groups write to the federal agency created in 2010 to bolster oversight of consumer financial products.

The major credit rating companies, for example, agreed to exclude only debts that have been paid off and unpaid debts of less than $500. Patients with larger medical bills they can't pay may still see their credit scores drop.

The groups also are asking the CFPB to eliminate deferred interest on medical credit cards. This arrangement is common for vendors such as CareCredit, whose loans carry no interest at first but can exceed 25% if patients don't pay off the loan in time.

Collection industry officials have lobbied against broader restrictions on credit reporting, saying limits would take away an important tool that hospitals, physicians' offices, and other medical providers need to collect their money and stay in business.

"We appreciate the challenges, but a broad ban on credit reporting could have some unintended consequences," said Jack Brown III, president of Florida-based Gulf Coast Collection Bureau, citing the prospect of struggling hospitals and other providers closing, which would reduce care options.

Brown, a past president of ACA International, the collection industry's leading trade association, warned that more medical providers would also start demanding upfront payment, putting additional pressure on patients.

To further protect patients from out-of-pocket costs like these, many advocates say hospitals, particularly those that are exempt from taxes because they are supposed to serve the community, must make financial aid more accessible, a key demand in the group's letters. "For too long, nonprofit hospitals have not been behaving like nonprofits," said Liz Coyle, executive director of the nonprofit Georgia Watch.

Charity care is offered at most U.S. hospitals. And nonprofit medical systems must provide aid as a condition of being tax-exempt. But at many medical centers, information about this assistance is difficult or impossible to find.

Standards also vary widely, with aid at some hospitals limited to patients with income as low as $13,590 a year. At other hospitals, people making five or six times that much can get assistance.

The result is widespread confusion that has left countless patients who should have been eligible for aid with large bills instead. A 2019 KHN analysis of hospital tax filings found that nearly half of nonprofit medical systems were billing patients with incomes low enough to qualify for charity care.

The groups are asking the IRS to issue rules that would set common standards for charity care and a uniform application across nonprofit hospitals. (Current regulations for charity care do not apply to for-profit or public hospitals.)

The advocates also want the federal agency to strengthen limits on how much nonprofit hospitals can charge and to curtail aggressive collection tactics such as foreclosing on patients' homes or denying or deferring medical care.

More than two-thirds of hospitals sue patients or take other legal action against them, such as garnishing wages or placing liens on property, according to a recent KHN investigation. A quarter sell patients' debts to debt collectors, who in turn can pursue patients for years for unpaid bills. About 1 in 5 deny nonemergency care to people with outstanding debt.

"Charitable institutions, which have other methods of collection available to them, should not be permitted to withhold needed medical care as a means to pressure patients to pay," the groups wrote.

No comments:

Post a Comment