Editor's Note -

The Country That Wants to ‘Be Average’ vs. Jeff Bezos and His $500 Million Yacht

Why did Rotterdam stand between one of the world’s richest men and his boat? The furious response is rooted in Dutch values.

by David Segal - NYT - July 29, 2022

ROTTERDAM, Netherlands — The image would have been a social media phenomenon: a few thousand citizens of the Netherlands’ second-largest city, standing beside a river and hurling eggs at the gleaming, new 417-foot sailing yacht built for Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and one of the world’s richest men. By the time the boat passed the crowd, it would have been spattered with bright orange yolk, plus at least one very bright spot of red.

“I would have thrown a tomato,” said Stefan Lewis, a former City Council member. “I eat mostly vegan.”

One recent afternoon, Mr. Lewis was standing near the Hef, as the Koningshaven Bridge is affectionately known, and explaining the anger that Mr. Bezos and Oceanco, the maker of the three-masted, $500 million schooner, inspired after making what may have sounded like a fairly benign request. The company asked the local government to briefly dismantle the elevated middle span of the Hef, which is 230 feet tall at its highest point, allowing the vessel to sail down the King’s Harbor channel and out to sea. The whole process would have taken a day or two and Oceanco would have covered the costs.

Also worth noting: The bridge, a lattice of moss-green steel in the shape of a hulking “H,” is not actually used by anyone. It served as a railroad bridge for decades until it was replaced by a tunnel and decommissioned in the early 1990s. It’s been idle ever since.

In sum, the operation would have been fast, free and disrupted nothing. So why the fuss?

“There’s a principle at stake,” said Mr. Lewis, a tall, bearded 37-year-old who was leaning against his bike and toggling during an interview between wry humor and indignation. He then framed the principle with a series of questions. “What can you buy if you have unlimited cash? Can you bend every rule? Can you take apart monuments?”

In late June, the city’s vice mayor reported that Oceanco had withdrawn its request to dismantle the Hef, a retreat that was portrayed as a victory of the masses over a billionaire, though it was much more than that. It was an opportunity to see Dutch and American values in a fiery, head-on collision. The more you know about the Netherlands — with its preference for modesty over extravagance, for the community over the individual, for fitting in rather than standing out — the more it seems as though this kerfuffle was scripted by someone whose goal was to drive people here out of their minds.

The first problem was the astounding wealth of Mr. Bezos.

“The Dutch like to say, ‘Acting normal is crazy enough,’” said Ellen Verkoelen, a City Council member and Rotterdam leader of the 50Plus Party, which works on behalf of pensioners. “And we think that rich people are not acting normal. Here in Holland, we don’t believe that everybody can be rich the way people do in America, where the sky is the limit. We think ‘Be average.’ That’s good enough.”

Ms. Verkoelen was among those who considered Oceanco’s request a reasonable concession to a company in a highly competitive industry. But she heard from dozens of infuriated voters, all of them adamantly opposed. She understood the origins of the fervor, which she illustrated with a story from her childhood.

“When I was about 11 years old, we had an American boy stay with us for a week, an exchange student,” she recalled. “And my mother told him, just make your own sandwich like you do in America. Instead of putting one sausage on his bread, he put on five. My mother was too polite to say anything to him, but to me she said in Dutch, ‘We will never eat like that in this house.’”

At school, Ms. Verkoelen learned from friends that the American children in their homes all ate the same way. They were stunned and a little jealous. At the time, it was said in the Netherlands that putting both butter and cheese on your bread was “the devil’s sandwich.” Choose one, went the thinking. You don’t need both.

Building the earth’s biggest sailing yacht and taking apart a city’s beloved landmark? That’s the devil’s all-you-can-eat buffet.

The streak of austerity in Dutch culture can be traced to Calvinism, say residents, the most popular religious branch of Protestantism here for hundreds of years. It emphasizes virtues like self-discipline, frugality and conscientiousness. Polls suggest that most people in the Netherlands today are not churchgoers, but the norms are embedded, as evidenced by Dutch attitudes toward wealth.

“Calvin teaches that you’re given stewardship over your money, that you have a responsibility to take care of it, which means giving lots of it away, being generous to others,” said James Kennedy, a professor of modern Dutch history at Utrecht University. “Work is a divine calling for which you will be held accountable. It’s considered bad for society and bad for your soul if you spend in ostentatious ways.”

There are billionaires in the Netherlands and a huge pay gap between chief executives and employees. Statista, a research firm, reported that for every dollar earned by an average worker, C.E.O.s earned $171. (The figure is $265 in the United States, the widest gap of any country.) The difference is that the rich in the Netherlands don’t flaunt it, just as the powerful don’t highlight their cachet. The Dutch once ran one of the world’s largest empires but there’s a certain pride here that the prime minister of the country rides a bicycle to pay visits to the king — yes, the Netherlands has a royal family, which is also relatively low-key — and locks the bicycle outside the palace.

There’s a premium on equality that has survived the country’s struggles to assimilate immigrants and a gentrification boom that is pricing the middle- and working-class out of cities. An ethos endures that nobody is any better than anyone else, or deserves more, and it stems from an unignorable geographic fact. Roughly one-third of the Netherlands is below sea level and citizens for centuries have had little choice but to band together to create an infrastructure of dikes and drainage systems to remain alive.

“The Netherlands is built on cooperation,” said Paul van de Laar, a professor of history at Erasmus University. “There were constant threats of disaster from the 15th and 16th century. Protestants and Catholics knew that to survive, they could not quarrel too much.”

Chip in. Blend in. Help others. These are among the highest ideals of the Netherlands. Does this sound like a country eager to cut some slack to a man with $140 billion and a $500 million boat?

It didn’t help that Dutch critics of Mr. Bezos believe that employees at Amazon are underpaid, which, given his fortune, strikes them as not just grotesquely unfair but immoral. “He doesn’t pay his taxes,” is a common refrain in this city, and it doesn’t mean that Mr. Bezos is considered a tax cheat. It means that he isn’t fighting inequality by sharing his money, an obligation that transcends the tax code.

(Emails to Amazon were not returned. Mr. Bezos did not respond to a ProPublica article last year, based on leaked Internal Revenue Service files, that showed he paid a tiny percent of his fortune in federal income taxes, using perfectly legal methods.)

The Rotterdam vs. Bezos brawl first made international headlines in February, when news broke that Oceanco had been granted city approval to briefly take apart the middle of the Hef. (The cost of this operation was never made public.) The assent had come from a civil servant who apparently didn’t see the harm. An uproar ensued.

“I thought it was a joke,” said Mr. Lewis, who learned about the permission on Facebook from incredulous friends. “So I called the vice mayor’s office and asked, ‘Is this for real?’ And they said, ‘We don’t know anything about this.’ It wasn’t on their radar. It took them a day to get back to me.”

When word of the accommodation reached the public, fuming residents became a staple of local TV news and a Facebook group formed to organize that mass egg pelting. (“Dismantling the Hef for Jeff Bezos’ latest toy? Come throw eggs…”) One aggrieved council member soon likened the masts of the yacht to a giant middle finger, pointed at the city.

Oceanco, which employs more than 300 people, has not spoken publicly about its decision to rescind its Hef request and did not respond to an email for comment. News reports stated that the company was concerned about threats against employees and about vandalism.

It’s unclear how the yacht, now known as Y721, will be completed. In February, the City Council’s municipality liaison, Marcel Walravens, was quoted in the media saying that it was impractical to float the mast-less yacht to another location and finish it there.

To Professor van de Laar, the real villain in this tale is not Oceanco or Mr. Bezos, who probably had never heard of the Hef. It’s the City Council, which completely misunderstood the depth of feelings about the bridge and bungled the messaging about its decision.

“Emotions are important,” he said. “The council didn’t grasp that, which is incredibly stupid.”

The issue wasn’t just this particular billionaire and this particular yacht. It was this particular bridge. To outsiders, the Hef looks like an ungainly industrial workhorse that no longer works.

That’s not what locals see. When opened in 1927 it was considered an architectural marvel, one celebrated by the Dutch documentarian Joris Ivens, in his 1928 film “The Bridge.”

“There are poems about the Hef,” said Arij De Boode, co-author of “The Hef: Biography of a Railroad Bridge.” “Anyone who makes a movie about Rotterdam includes the Hef. It’s more than a bridge.”

Rotterdam is one of the few European cities in which nearly all the buildings, both commercial and residential, are new because the place was bombed to devastating effect by the Nazis in World War II. It turned this into a city of the future, always looking ahead, tearing down whatever doesn’t work or isn’t needed.

Except for the Hef. It has become the city’s most recognizable landmark. After the war, it became a symbol of resilience and to locals of an older generation, the Hef is a rare link to the past.

When there was talk decades ago of tearing it down, residents protested. It was declared a national monument in 2000 and underwent a three-year restoration that ended in 2017. Today, the Hef stands as a triumph of function over form that no longer functions, a monolith that can’t be altered, even temporarily — no matter who asks, no matter the price.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/29/business/bezos-yacht-rotterdam.html

The Debt Crisis That Sick Americans Can’t Avoid

by Elizabeth Rosenthal - Kaiser Health News - August 2, 2022

President Joe Biden’s campaign promise to cancel student debt for the first $10,000 owed on federal college loans has raised debate about the fairness of such lending programs. While just over half of Americans surveyed in a June poll supported forgiving that much debt incurred for higher education, 82% said that making college more affordable was their preferred approach.

But little public attention has been focused on what is — statistically, at least — a bigger, broader debt crisis in our country: An estimated 100 million people in the U.S., or 41% of all adults, have health care debt, compared with 42 million who have student debt.

The millions under the weight of medical debt deserve help, both because medical debt is a uniquely unfair form of predatory lending and because of its devastating ripple effects on American families.

Unlike college tuition or other kinds of debt, outlays for medical treatments are generally not something we can consider in advance and decide — yes or no — to take on. They are thrust upon us by illness, accident, and bad luck. Medical treatment generally has no predictable upfront price and there is no cap on what we might owe. And, given our health system’s prices, the amount can be more than the value of the family home if incurred for a hospital stay.

When it was time for my kids to choose a college, I knew in advance almost exactly what it would cost. We could decide which of the different tuitions was “worth it.” We made a plan to pay the amount using bank accounts, money saved in college savings plans, some financial aid, a student job, and some money loaned by a grandparent. (Yes, we had enough resources to make a financially considered choice.)

Think about how different educational debts are from those incurred in health care. In one case, profiled by KHN, the parents of twins, who were born at 30 weeks, faced out-of-pocket bills of about $80,000 stemming from charges in neonatal intensive care and other care that insurance didn’t cover. In another case, a couple ended up owing $250,000 when one spouse went to the emergency room with an intestinal obstruction that required multiple surgeries. They had to declare bankruptcy and lost their home. Even smaller bills lead to trashed credit ratings, cashing in retirement accounts, and taking on second jobs; in surveys, half of adults in the U.S. say they don’t have the cash to pay an unexpected $500 medical bill.

In “taking on” medical debt, patients sign only the sort of vague financial agreement that has become ubiquitous in American health care: “I agree to pay for charges my insurance doesn’t cover,” presented on the stack of forms to sign on arrival at an emergency room or a doctor’s office. But no one can fully consider options or say “no” to care while in pain or medical distress or even properly agree to pay an unknown amount.

Student debt causes hardships because it hits people who’ve just started careers, with salaries at the bottom of the pay scale, forcing them to delay life choices, like purchasing a home or starting a family. But medical debt often comes with all that plus medical woes: In a KFF poll, 1 in 7 people with health care debt said they’d been denied care by a provider because of unpaid bills. Sometimes a bill for as little as a few hundred dollars can turn into a collections nightmare.

Already, the federal government is stepping in to assist student loan borrowers. It has paused student debt payments during the pandemic, and the Biden administration has announced that it would forgive student debt for tens of thousands of public sector workers. Late last year, the Department of Education announced that it would no longer contract with outside debt collectors but would instead deal with loan defaults and potential defaults itself to better “support borrowers.”

Medical debt collection has typically been outsourced to aggressive private agents and the for-profit medical debt collection industry; there are few guardrails. Recently, consumer credit reporting agencies have said they will no longer put small medical debts on credit reports and remove medical debts that have been paid. For many people, that will take years. Some 18% of Americans with health care debt said they never expect to be able to pay off their debt.

The irony here is that medical debt is sometimes discharged in bulk by charities, like RIP Medical Debt and church groups, which will pay pennies on the dollar to make patients’ outstanding medical debt disappear. The absurdity of this fix was shown when the comedian John Oliver, in a late-night stunt, cleared $15 million of Americans’ debt after buying it for $60,000.

But medical debt isn’t a joke and now harms a broad swath of Americans. The government could act in the short term to relieve this uniquely American form of suffering by buying the debts for a modest price. And then, it needs to tackle the underlying cause: a health care system that denies millions of people adequate care while still being the most expensive in the world.

Our View: The number of uninsured Americans is at an all-time low. Let’s keep it that way

If Congress doesn't act, then millions of Americans could lose health coverage at the end of the year.

The expansion of Medicaid in Maine was billed as a way to get health coverage to more vulnerable residents. Nearly four years later, it’s living up to that promise.

Now, it’s up to Congress to protect those benefits, as well as others that have led to a historic, healthy drop in the number of uninsured Americans.

According to a new federal report, the number of uninsured low-income Mainers fell nearly 5 percentage points, from 21.3 percent to 16.5 percent, between 2018 and 2020.

The drop came following Gov. Mills’ executive order to expand Medicaid – or MaineCare, as it’s called here – which she signed on her first day in office, Jan. 3, 2019.

Expansion was enabled under the Affordable Care Act, and Maine voters had approved it at the polls in 2017. But its implementation was blocked by then-Gov. Paul LePage, who was a longtime opponent of the measure, saying it would threaten to put the state in “red ink.”

As we near the end of Mills’ first term, the state’s finances are more than fine.

And as of late last year, more than 80,000 Mainers had enrolled as part of Medicaid expansion, giving Maine the third-highest drop in uninsured low-income residents of any state in that time period.

The same is happening across the country, as other holdouts from Medicaid expansion finally put the program in place. The federal public health emergency rolled out in response to COVID-19 blocked states from dropping anyone off Medicaid, too, keeping the rolls high.

Additionally, the American Rescue Plan passed last year by Congress included enhanced subsidies for coverage through the ACA exchanges, helping to fuel record enrollment.

Together, all of it put the national uninsured rate at an all-time low: 8 percent as the first quarter of the year, with 5.2 million Americans gaining coverage since 2020.

What’s more, the rate of uninsured children, which increased in 2019 and 2020, fell too.

The uninsured rate, one of the main targets of the ACA, was around 15 percent when that federal legislation passed in 2010. Now it’s almost half that.

That’s a lot more people who are enjoying the benefits of health coverage. Access to Medicaid expansion, federal researchers found, was associated with lower out-of-pocket spending and improvements in primary and preventative care.

That’s the good news. The bad news is, millions of them could lose coverage if Congress doesn’t act.

The enhanced subsidies run out at the end of the year. According to a report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, that could force 3 million people to lose coverage. Others will see price hikes, or opt to narrow their coverage in order to save money.

The federal public health emergency also runs out this year, and states will again be allowed to determine who is eligible for Medicaid– and who isn’t. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates the change will cause 13 percent of enrollees to lose coverage. That’s millions of Americans.

Congress needs to extend the ACA subsidies past this year, which would also help any Medicaid recipients who get dropped from the program once the public health emergency lapses. States should do whatever they can to help people navigate their health coverage options, so that they don’t lose benefits they’re entitled to.

A decade ago, the number of uninsured Americans was a five-alarm crisis. Since then, millions have gained the benefits of health coverage. It’s no time to go back now.

About That Health Graph You Saw Online ...

"They'd Just as Soon Kill You as Look at You"

Absolute Zero: A Newsletter from Richard (RJ) Eskow - August 3, 2022

When I was growing up in the Rust Belt, there was a phrase people would use to describe an unusually vicious or cold-blooded kid in the neighborhood (and there were a few). “He’d just as soon kill you as look at you,” they would say.

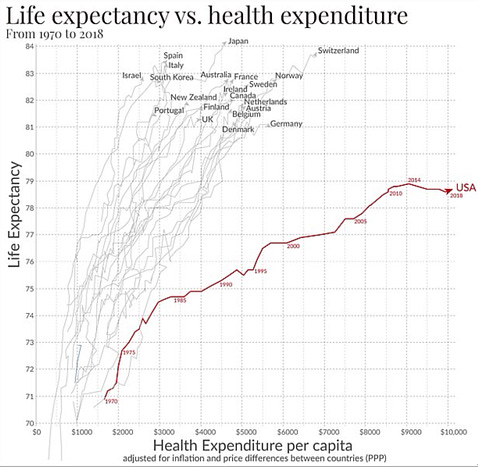

I thought of that phrase when a graph went around recently on left-leaning social media comparing life expectancy and health care costs in the United States with those in other industrialized countries. It went viral, even though the information it contained has been widely discussed for years. That’s the power of a well-crafted image.

Why are our costs so much higher and our health care outcomes so much worse? There are a number of reasons, but the most important one is: our health financing system is sociopathic. That’s not hyperbole. Ours is a system that would, quite literally, “just as soon kill you as look at you.”

The graph can be seen above. A little digging revealed that this image was produced by Max Roser, who runs a website called Our World in Data (ourworldindata.org).

About this graph:

It doesn’t include the disabilities, loss of productivity, economic stagnation, and poor quality of life created our inferior health system.

It doesn’t break out the vast disparities in American healthcare outcomes by race or class.

It ends in 2018, so it doesn’t include the more than one million people who have died so far from Covid-19 in this country, much less those who died elsewhere.

Nor does it include the billions of dollars the government directed to private pharmaceutical companies and other vendors during the pandemic, only to have them overcharge us for the products they then developed at public expense.

And remember: when we talk about longevity, we’re not just talking about people losing the last few years of life,. That’s tragic enough. But infant and child mortality bring down the curve, too, as does premature death at all ages.

Racial Disparities

During the decades covered by this graph, Black infant mortality rates were 2.5 times that of Whites. Race is a longtime predictor of health outcomes. These statistics, which I prepared for Bernie Sanders before a Baltimore speech in 2016, are all too representative of Black America’s experience:

If you're born in Baltimore's poorest neighborhood, your life expectancy is almost 20 years shorter than if you're born in its richest neighborhood.

15 Baltimore neighborhoods have lower life expectancies than North Korea. Two of them have higher infant mortality than Palestine’s West Bank.

Baltimore teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19 face poorer health conditions and a worse economic outlook than those in economically distressed cities in Nigeria, India, China, and South Africa, according to a 2015 report from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Here's another statistic: Black children are seven to ten times more likely to die of asthma than white children. That’s one I take personally, since I nearly died of asthma myself as a child (despite being white) and it’s a terrible way to go.

I could muster more facts and figures, but you get the idea. The racialized nature of the American healthcare system – which is instrumentalized through economic discrimination – both disables and kills. That’s why, since the arrival of Covid-19, age-adjusted statistics show that Black Americans have been especially hard hit, with death rates that are approximately 67% higher than those of Whites and approximately 2.2 times higher than those of the group with the lowest adjusted death rates (Asian Americans).

Class Kills

White America is catching up, at least its poorer neighborhoods. “Deaths of despair” – suicide, opioid addiction, and alcoholism – were ravaging lower-income White American men even before the pandemic, contributing to the USA’s declining life expectancy (as seen in the graph above).

A paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) showed that living in an area with high economic inequality was, like race, a strong predictor of Covid deaths. In 2020, nearly 46,000 people in the United States killed themselves. White men, who make up 30 percent of the population, committed 70 percent of the suicides.

Class is a killer.

Indifferent to Suffering

Our healthcare system is the most direct killer of all. It is designed to be indifferent to human suffering, to life and death. To this system, it doesn’t matter whether a person lives or dies as long as it gets paid. That’s why our healthcare costs are so high, even though our life expectancy is so low.

Medical providers and institutions get paid for the services they provide, whether you live or die. The more services they provide, the more money they make. Health insurers operate under an even more perverse set of incentives. Their rates are based on the overall volume of services expected, which they then mark up. Their business practices are designed to shift as much cost as possible to the patient, while at the same time restricting the patient’s freedom to choose. They drive patients to providers who accept the insurance company’s low rates and agree to its restrictive rules about medical care.

That system is designed to be expensive. Let’s say you’re paying for a plan with a $5,000 deductible. As Sarah Kliff and Josh Katz documented for the New York Times, a colonoscopy at the University of Mississippi Medical Center will cost you $1,463 with a Cigna plan and $2,144 with an Aetna plan. If, on the other hand, you have no insurance at all, that colonoscopy will cost you “only” $782.

Kliff also reported on the case of a couple whose baby died while in the hospital. Although they had insurance through Cigna, the couple subsequently received a bill for $257,000 in what was described as “a dispute between a large hospital and a large insurer, with the patient stuck in the middle.” This system is indifferent to the trauma it inflicts on patients or their survivors.

It's About the Incentives

Outcomes are also a matter of indifference. People are billed, no matter what happens. One study found that the average cost of treating accidents in the United States with fatal outcomes is $6,880 if the patient dies in the emergency room and $41,570 if they die in the hospital.

Some historians claim that ancient court physicians in Asia were paid for every month their patients remained healthy. That may or may not be a myth. What is definitely not a myth is that, in many publicly-funded health systems worldwide, health professionals are paid by salary and not by volume, while hospitals are given a fixed (or “global”) budget to provide care. That creates less of an incentive for “churning” patients and more of an incentive to focus on patient care.

That’s the kind of system we should have. Instead, we have a system where they charge $2,144 for a colonoscopy and $41,570 for an unsuccessful treatment. That’s a system where they’d just as soon kill you as look at you. It doesn’t matter. They make money either way.

No comments:

Post a Comment