The days of full covid coverage are over.

Insurers are restoring deductibles and co-pays,

leaving patients with big bills.

Large insurance companies waived cost-sharing for coronavirus care in 2020, but it has sprung

back in 2021

by Christopher Rowland - Washington Post - September 18, 2021

Now Azar, who earns about $36,000 a year as the director of a preschool at a Baptist church in Georgia, is facing thousands of dollars in medical expenses that she can’t afford.

“I’m very thankful to be home. I am still weak. And I’m just waiting for the bills to come in to know what to do with them,” she said Wednesday, after returning home.

In 2020, as the pandemic took hold, U.S. health insurance companies declared they would cover 100 percent of the costs for covid treatment, waiving co-pays and expensive deductibles for hospital stays that frequently range into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But this year, most insurers have reinstated co-pays and deductibles for covid patients, in many cases even before vaccines became widely available. The companies imposed the costs as industry profits remained strong or grew in 2020, with insurers paying out less to cover elective procedures that hospitals suspended during the crisis.

Now the financial burden of covid is falling unevenly on patients across the country, varying widely by health-care plan and geography, according to a survey of the two largest health plans in every state by the nonprofit and nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation.

If you’re fortunate enough to live in Vermont or New Mexico, for instance, state mandates require insurance companies to cover 100 percent of treatment. But most Americans with covid are now exposed to the uncertainty, confusion and expense of business-as-usual medical billing and insurance practices — joining those with cancer, diabetes and other serious, costly illnesses.

(Insurers continue to waive costs associated with vaccinations and testing, a pandemic benefit the federal government requires.)

A widow with no children, Azar, 57, is part of the unlucky majority. Her experience is a sign of what to expect if covid, as most scientists fear, becomes endemic: a permanent, regular health threat.

The carrier for her employee health insurance, UnitedHealthcare, reinstated patient cost-sharing Jan. 31. That means, because she got sick months later, she could be on the hook for $5,500 in deductibles, co-pays and out-of-network charges this year for her care in a Georgia hospital near her home, including her ICU stay, according to estimates by her family. They anticipate she could face another $5,500 in uncovered expenses next year as her recovery continues.

Bills related to her stay at the out-of-network rehab hospital in Tennessee could climb as high as $10,000 more, her relatives have estimated, but they acknowledged they were uncertain this month what exactly to expect, even after asking UnitedHealthcare and the providers.

“We still don’t know where the numbers will land because the system makes the family wait for the bills,” said Azar’s sister, Rebecca Straub.

UnitedHealthcare declined to comment specifically about Azar’s situation unless she signed a blanket waiver allowing release of all her health records — which she declined.

In general, a person with Azar’s type of plan would have an in-network deductible of $1,500 and an in-network out-of-pocket maximum of $4,000, said UnitedHealthcare spokeswoman Tracey Lempner in an email. Lempner declined to say what a patient’s out-of-network, out-of-state share would be at the Tennessee rehab hospital.

She did not respond directly to a question about why UnitedHealthcare chose Jan. 31 to stop waiving deductibles and co-pays for covid treatment.

“The cost-share waivers were just one piece of our overall response to the covid-19 pandemic,” Lempner said. “We have focused our efforts around helping our members get access to covid-19-related tests, vaccines and treatment, while providing additional support to our clients, care providers and local communities.” UnitedHealthGroup, UnitedHealthcare’s parent company, reported $15.4 billion in profits in 2020, up from $13.8 billion in 2019.

The charges Azar anticipates would be budget-crushers, Straub said. Her relatives are seeking help from the public on a nonprofit patient-fundraising website called Help Hope Live, which says it verifies the circumstances of each patient’s condition with medical providers.

In a Facebook video call from her hospital bed in Chattanooga last week, Azar cited prayer from family and friends for helping her maintain a positive attitude. Although she considers the change in insurance practices unjust for people who get sick this year, she said she harbors no personal animosity toward UnitedHealthcare.

“I got here a year late, huh?” she quipped. “Even though it may not seem fair or seem right, it’s where we are.”

She said her doctors surmised she may have already been exposed to the coronavirus when she received her Johnson & Johnson shot in July.

The lack of uniformity in covid insurance practices across the country this year is striking. In some places, because of differences in health plan policies, covid patients in the same hospitals and in the same ICU units could be facing completely different financial burdens.

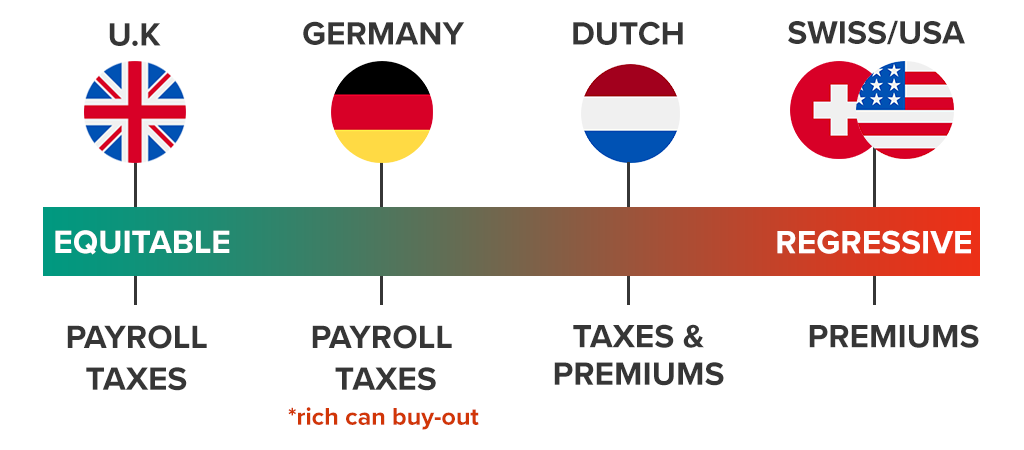

“There was no federal mandate for insurers to cover all the costs for covid treatment. Insurers were doing it voluntarily,” said Krutika Amin, a Kaiser Family Foundation associate director who researchers health insurance practices.

Last year, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 88 percent of people covered by private insurance had their co-pays and deductibles for covid treatment waived. By August 2021, only 28 percent of the two largest plans in each state and D.C. still had the waivers in place, and another 10 percent planned to phase them out by the end of October, the Kaiser survey found. Its survey this year of employer-sponsored plans reflected similar patterns.

“For some people, deductibles can be over $8,000 for a hospital stay,” Amin said. “It will really depend on what plan they have.”

America’s Health Insurance Plans, the industry’s lobbying and trade group, said insurance companies began to reinstate cost-sharing for covid treatment as vaccines became available and in recognition that the coronavirus will be an ongoing health challenge.

“After a year and a half, it’s pretty clear that covid is here to stay, that this is a continuing health condition,” AHIP spokesman David Allen said. “When it comes to treatment, we’re looking at it like we would treat any other health condition.”

The industry says it is not using the return of deductibles as financial incentive for people to get vaccines. To encourage vaccinations, the industry is focused on ``carrots, not sticks,” Allen said, with programs targeting education and making sure no one is billed for receiving vaccines.

In Painesville, Ohio, Becky Calderone, a hairdresser and graphic artist, has been contending with a steady stream of bills and collection notices for seven months, she said, after she and her husband were both stricken with covid in February. Her husband was hospitalized; she was not. Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, which was provided through her spouse’s employer, reimposed patient cost-sharing for covid treatment Jan. 31.

Calderone and her husband did not fit the criteria for early vaccine supplies, which were targeted in January and February toward the elderly. The couple did not get vaccinated until May, well after they got sick.

“We were stuck in this gap," Calderone said. Thirty days after her husband’s release from the hospital, she said, “the bills started coming in like a flood.”

Calderone described navigating a bureaucratic odyssey of emails and appeals with Anthem as well as contact with state insurance regulators. Now she is receiving letters “up the wazoo” from collections agencies. Anthem agreed to waive her husband’s deductibles, she said, but the bills from various providers are still inexplicably arriving. Her deductibles remain in place, she said, but she has not been told why.

Calderone said the financial hardships may mount even further. The couple has a new insurance company now, because her husband changed jobs, so they will have to meet another set of deductibles and co-pays this year as they battle long-hauler covid symptoms, including irregular heartbeats and chronic fatigue, she said.

Anthem did not respond to requests for comment specifically about Calderone’s claims. A spokesman said Calderone would need to sign a waiver to release medical information. Calderone declined.

In a general statement, the company said its waivers last year were one of a number of steps it took to help its members manage the impacts of the virus.

“These waivers ended in January as we all had gained a better understanding of the virus, and people and communities became more familiar with best practices and protocols for limiting COVID-19 exposure and spread,” the company said in a statement. “Also, at this time vaccines, which are proven to be the safest and most effective way to protect oneself from COVID-19, were starting to become readily available.”

Anthem took in $4.6 billion in profits in 2020, compared to $4.8 billion in 2019.

The reintroduction of cost-sharing mainly affects people with private or employer-based insurance. Patients with no insurance can have 100 percent of their expenses covered by the federal government, under a special program set up by the government for the pandemic, with hospitals reimbursed for care at Medicare rates.

Covid patients with Medicaid, the government plan for lower-income people that is paid for by states and the federal government, continue to be protected from cost-sharing, insurance specialists said. Patients on Medicare, the federal plan for the elderly, could face out-of-pocket costs if they do not have supplemental insurance.

For large commercial plans, the pandemic created an unusual dynamic in 2020. Hospitals stopped performing elective procedures, because of the risk of infection and because they were overwhelmed in many communities, so insurance companies had to pay out fewer claims.

“Insurers may have also wanted to be sympathetic toward pains patients, and some may have also feared the possibility of a federal mandate to provide care free-of-charge to COVID-19 patients, so they voluntarily waived these costs for at least some period of time during the pandemic,” the Kaiser Family Foundation report said.

Nationally, covid hospitalizations under insurance contracts on average cost $29,000, or $156,000 for a patient with oxygen levels so low that they require a ventilator and ICU treatment, according to data gathered by the national independent nonprofit FAIR Health.

“Insurers wanted to encourage people to get treatment. And this was something that, almost more than any illnesses and health conditions, was something that you have no control over,'' said Jack Hoadley, research professor emeritus at the Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms. “The insurers probably had a sense that there was a moral obligation to not put patients on the spot for this kind of thing.”

Insurance companies participating in Affordable Care Act marketplaces also faced the prospect of having to pay rebates to the government if their profit ratios exceeded certain levels.

The calculus in place in 2020 changed with the advent of vaccines, which now makes most hospitalizations preventable, Hoadley said.

In some cases, the patchwork of policies and plans is creating stark differences in circumstances for individual patients in the same facility.

Hospitals along the Connecticut River, the border between Vermont and New Hampshire, draw patients from both states. Vermont health plans are waiving deductibles and co-pays into 2022. In New Hampshire, where Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield has a dominant presence, insurance companies have reinstated cost-sharing.

Marvin Mallek, a doctor who treats covid patients from both sides of the river at Springfield Hospital in Vermont, said New Hampshire covid patients are now facing business as usual from insurers, suffering the same sort of financial stress that routinely affects patients with cancer, heart disease and other serious ailments.

“The inhumanity of our health-care system and the tragedies it creates will now resume and will now cover this one group that was exempted,'' he said. “The U.S. health-care system is sort of like a game of musical chairs where there are not enough chairs, and some people are going to get hurt and devastated financially.”

Hospitals also are in the position of having to resume billings and collections for individuals who may have been laid off because of the pandemic or been too sick to work, experts said.

“If you ever wanted a study in differential treatment, this is it,” said Ray Berry, chief executive officer of his own company, Health Business Solutions, in Cooper City, Fla., and a member of the North Broward Hospital board. “You can have people in beds right next to each other, and one can pay $3,000 and one can pay nothing. … The folks who do pay it are going to get sticker shock.”

Their Baby Died in the Hospital. Then Came the $257,000 Bill.

A New York family had good health insurance. But the bills for their daughter’s care started showing up and kept coming.

Brittany Giroux Lane and her husband, Clayton, are still caught in a billing dispute between hospital and insurer after the death of their daughter in 2019.

by Sarah Kliff - NYT - September 21, 2021

Brittany Giroux Lane gave birth to her daughter, Alexandra, a few days before Christmas in 2018. The baby had dark eyes and longish legs. She had also arrived about 13 weeks early, and weighed just two pounds.

Alexandra initially thrived in the neonatal intensive care unit at Mount Sinai West. Ms. Lane, 35, recalls the nurses describing her daughter as a “rock star” because she grew so quickly. But her condition rapidly worsened after an infection, and Alexandra died early on the morning of Jan. 15 at 25 days old.

A flurry of small medical bills from neonatologists and pediatricians quickly followed. Ms. Lane struggled to get her breast pump covered by insurance because, in the midst of a preterm birth, she hadn’t gone through the health plan's prior approval process.

Last summer, Ms. Lane started receiving debt collection notices. The letters, sent by the health plan Cigna, said she owed the insurer over $257,000 for the bills it accidentally covered for Alexandra’s care after Ms. Lane switched health insurers.

Ms. Lane was flummoxed: It was Cigna that had received the initial bill for care and had paid Mount Sinai West. Now, Cigna was seeking the money it had overpaid the hospital by turning to the patient.

“For them, it’s just business, but for us it means constantly going through the trauma of reliving our daughter’s death,” said Clayton Lane, Alexandra’s father and Ms. Lane’s husband. “It means facing threats of financial ruin. It’s so unjust and infuriating.”

Medical billing experts who reviewed the case described it as a dispute between a large hospital and a large insurer, with the patient stuck in the middle. The experts say such cases are not frequent but speak to the wider lack of predictability in American medical billing, with patients often having little idea what their care will cost until a bill turns up in the mail months later.

Congress passed a ban on surprise medical bills last year, which will go into effect in 2022. It outlaws a certain type of surprise bill: those that patients receive from an out-of-network provider unexpectedly involved in their care. There are plenty of other types of bills that surprise patients, such as those received by the Lanes, that are likely to persist.

The Lanes describe the process of fighting their surprise bill as frustrating and Kafkaesque. They have spent hours on the phone, sent dozens of emails, and filed complaints with regulatory agencies in two states.

“The letters mean I’m constantly reliving the day, and that is such a hard space to be in,” Ms. Lane said. “I feel so frustrated that the hospital is making decisions about their own bottom line that influence our potential future, and the memory of our child.”

“This patient had no control over what was paid, and she has no control over whether it gets returned,” said Susan Null, a medical billing expert with the firm Systemedic Inc. “Sometimes things like this might be done to motivate the patient to contact the hospital, to get them to release the funds.”

Americans are familiar with medical debt: About 18 percent of them have an outstanding bill from a hospital, doctor or other type of provider in the health system. But most do not expect to get collection notices for bills that were already paid by their health plan.

Courtney Jones, a senior case manager with the Patient Advocate Foundation, described working on cases in which patients have received similar collection notices for bills that the insurer, not the patient, was responsible for covering. It usually happens with large medical bills, as with the Lanes, in which the insurer and hospital both have more at stake.

“They use it as a tactic to put some pressure on the medical facility to refund the money,” Ms. Jones said.

In a response to questions from The New York Times, Cigna said it “regrets” the letters and, in light of the Lanes’ experience, was now reviewing how it communicates with patients in such cases.

After the Lanes filed a complaint to a state regulator, Cigna sent them a letter stating they would no longer receive similar letters. “We empathize with the pain and confusion this experience has caused for Mr. and Ms. Lane,” it said in a statement. “We are working with our vendor to ensure this doesn’t happen again to the Lanes or any other customer.”

Ms. Lane received the first collection notice about 18 months after her daughter’s death. Her family had switched health plans in the middle of Alexandra’s hospital stay because of a change in employment.

The day Ms. Lane went into labor with Alexandra was supposed to be her last day at the first job, before starting a new position a few weeks later.

“I was terrified of getting hit with a massive bill, so even while I was in labor I was updating my insurance with Mount Sinai,” Ms. Lane recalled.

The hospital appeared to have both insurance plans on file — Cigna for 2018 coverage, and UnitedHealthcare for 2019. But Cigna accidentally covered the entire bill, overpaying $257,000 for the baby’s care in January that should have been paid by UnitedHealthcare.

A Mount Sinai representative told the Lanes that UnitedHealthcare did in fact pay the bill — meaning the bill was paid twice — but that did not resolve what appears to be a wider issue that Mount Sinai has with Cigna.

When Ms. Lane received the first collection notice, she contacted the hospital. A patient services representative apologized and, over email, wrote that “Cigna is going to receive back” the overpayment. The third-party contractor that sent the letter, on Cigna’s behalf, also told her the matter would be settled within days.

“I was supposed to get a confirmation; I didn’t, but I was exhausted and I didn’t follow up,” she said.

She realized the refund never happened when another collection notice arrived this summer, in early July. When she reached out to the hospital agan, a top executive said she did not know when the refund would be released.

“I can’t give you a response about the refund due to Cigna as it is being discussed as part of a larger settlement agreement that is ongoing,” Gail Spiro, Mount Sinai’s assistant vice president for patient financial services, wrote in an Aug. 10 email. “I apologize again for how long it’s taken to get you what you need.”

In a statement, Mount Sinai West said: “It is normal business practice to reconcile accounts with insurers in this manner. It is not typical for an insurer to pursue a patient in this way.”

The Lanes have also had several phone calls with Cigna and ultimately filed a complaint with the insurance department in California, where their Cigna health plan was registered.

“Getting another letter was completely disruptive to our lives and our healing,” Mr. Lane said. “It meant a lot of tears.”

In a response to that complaint, Cigna sent the Lanes a letter stating the notices were sent in error by a third party vendor called HMS, which the insurer uses to monitor overpayments to hospitals. The letters were meant only to “inform” the family about the continuing dispute with Mount Sinai, the Cigna letter said.

The notices that the Lanes received both informed them of the debt and asked them to “pay in full” within 30 days, using a slip at the bottom of the letter meant to be sent back with payment.

HMS declined to comment for this article, citing its patient privacy practices. The Lanes have requested that Mount Sinai and Cigna provide statements on letterhead that the family does not owe this debt. No such letter has yet been provided, although Mount Sinai says it will issue one in coming weeks.

The Lanes said it was difficult to reconcile the kind and loving care their daughter received in the neonatal intensive care unit with the billing experience that followed.

“She died surrounded by people who cared for her so lovingly and wonderfully,” she said. “We continue to support the NICU directly, so we can help families that are there.”

Since Alexandra’s death, the Lanes have donated supplies to the Mount Sinai West neonatal unit, including infant rockers; books about caring for premature babies; and a camera with a photo printer (taking baby pictures can be hard, they learned; phones are often not allowed because of hygiene concerns). The family is also now welcoming a new addition: They are adopting a baby boy.

“He’s six weeks now, and we’re definitely falling in love,” Ms. Lane said. “There are a lot of firsts, though, that should be seconds — the first time he smiled was a first for him, but should have been a second for us. There is a lot of joy, but also a lot of secondary loss, and a lot of thinking of Alexandra.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/21/upshot/hospital-bills-baby-death.html

This Lab Charges $380 for a Covid Test. Is That What Congress Had in Mind?

Insurers say it’s price-gouging, but a law left an opening for some labs to charge any price they wished.

by Sarah Kliff - NYT - September 26, 2021

At the drugstore, a rapid Covid test usually costs less than $20.

Across the country, over a dozen testing sites owned by the start-up company GS Labs regularly bill $380.

There’s a reason they can. When Congress tried to ensure that Americans wouldn’t have to pay for coronavirus testing, it required insurers to pay certain laboratories whatever “cash price” they listed online for the tests, with no limit on what that might be.

GS Labs’s high prices and growing presence — it has performed a half-million rapid tests since the pandemic’s start, and still runs thousands daily — show how the government’s longstanding reluctance to play a role in health prices has hampered its attempt to protect consumers. As a result, Americans could ultimately pay some of the cost of expensive coronavirus tests in the form of higher insurance premiums.

Many health insurers have refused to pay GS Labs’ fees, some contending that the laboratory is price-gouging during a public health crisis. A Blue Cross plan in Missouri has sued GS Labs over its prices, seeking a ruling that would void $10.9 million in outstanding claims.

In court last month, the insurer claimed that the fees were “disaster profiteering,” and in violation of public policy.

Omaha-based GS Labs contends the exact opposite: that it has public policy on its side, pointing to the CARES Act passed in 2020. “Insurers are obligated to pay cash price, unless we come to a negotiated rate,” said Christopher Erickson, a partner at GS Labs.

The requirement that insurers pay the cash price applies only to out-of-network laboratories, meaning those that have not negotiated a price with the insurer. There are signs other laboratories may be acting like GS Labs: A study published this summer by America’s Health Insurance Plans, the trade association that represents insurers, found that the share of coronavirus tests conducted at out-of-network facilities rose to 27 percent from 21 percent between April 2020 and March 2021.

It found that the average price for a coronavirus test at an in-network facility was $130, a figure that includes both rapid tests and the more widely used, and more expensive, PCR tests. About half of out-of-network providers are charging at least $50 more than that.

The $380 cash price is posted on the GS Labs website. In legal documents, it has said that it pays “approximately $20” for the rapid test itself. Mr. Erickson says the high price reflects the “premium service” they provide patients, as well as the $37 million in start-up costs associated with building their laboratory network in less than a year.

“You can book 15 minutes out with us on any given day, and get your results in 15 to 20 minutes,” Mr. Erickson said, pointing to the scarcity of testing at many drugstores. “We have a nursing hotline where you can get your results interpreted. Our pricing is one of the most expensive in the nation because we have the best service in the nation.”

Health policy experts who reviewed the GS Labs prices said that, even with the company’s investment in its service, it was hard to understand why their tests should cost eight times the Medicare rate of $41.

“This is not like neurosurgery where you might want to pay a premium for someone to have years of experience,” said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown who has studied coronavirus testing prices.

Even though she felt its price was exceptionally high, Ms. Corlette and other experts said GS Labs had strong legal grounds to continue charging it because of how Congress wrote the CARES Act. “Whatever price the lab puts on their public-facing website, that is what has to be paid,” she said. “I don’t read a whole lot of wiggle room in it.”

GS Labs is owned by City+Ventures, a real estate and investment firm. It started its first testing site last October and, at its peak, operated 30 locations across the country.

As it began increasing testing last year, it inquired about becoming an in-network provider, offering what it described as “substantial discounts” in return for reliable and prompt payments. The company declined to specify the exact size of its discount, but said that insurers generally rejected its proposals.

GS Labs said it felt insurers were hostile to its new operation. Some sent their members explanation-of-benefit documents, showing that the claim had been denied and that the patient might have to pay the full amount.

GS Labs says it does not pursue fees directly from patients, which would violate federal law, and says those mailings were a tactic to turn customers against its business.

“They try to paint us in a bad light when they’re the ones not following federal law,” said Kirk Thompson, another GS Labs partner. “Insurers have made a decision to ignore their obligations or justify not following the CARES Act.”

Insurers describe the interactions differently. They say they are doing their best, within the bounds of federal law, to protect patients from unnecessary high fees that will ultimately drive up premiums.

UPMC Health Plan in Pittsburgh first became aware of GS Labs when it saw an unusual pattern on its claims: The vast majority included a rapid antigen test alongside a Covid antibody test. Of all claims the health plan received from any laboratory with this combination of billing codes, it said 91 percent came from GS Labs.

“There is very little reason to order both of those tests on the same day,” said Stephen Perkins, the health plan’s chief medical officer. “They serve very different purposes, and they would not be systematically ordered as a result of suspected Covid exposure.”

The health plan saw this as evidence that GS Labs was gaming the CARES Act: Insurers are required to fully cover antigen and antibody tests. “The CARES Act governs what we can and can’t do, and we can’t refuse to pay for the double billing,” he said.

GS Labs says that it offers patients a “menu of tests,” and that the patient chooses which ones to get.

The UPMC health plan has decided, however, to challenge GS Labs pricing in other ways. At one point, the plan’s legal staff noticed the laboratory advertised a 70 percent coupon available to cash-pay patients, which would bring the price down to $114. The coupon has since been removed from the GS Labs website.

“We told GS Labs that we believed that was their cash price, and that is what we are now paying them,” said Sheryl Kashuba, the plan’s chief legal officer.

Evan White, general counsel at City+Ventures, said his company was still evaluating “next steps” with the health plan. “We are by no means content with what they have self-imposed as their rate,” he said.

What actually counts as the GS Labs cash price — and whether insurers will ultimately have to pay it — may be settled in Congress or the courts.

In July, Blue Cross Blue Shield Kansas City argued in a lawsuit against GS Labs that the discounted price sometimes offered to patients who cover the test themselves — the $114 fee that UPMC Health Plan also discovered — is the company’s actual cash price.

“GS Labs knowingly and willfully executed a scheme or artifice to defraud health insurers and plans by posting a sham cash price,” the health plan said in its legal brief, “and then demanding that group health plans and insurers pay those same sham cash prices.”

GS Labs has responded that just because it gave discounts to some patients, that does not mean insurers are “entitled to pay only a small fraction of the published cash price.” It has countersued the Blue Cross plan, contending the plan must pay nearly $10 million for 34,621 outstanding claims.

Congress, legislating quickly amid a health crisis in 2020 and settling on policies that would be easy to roll out, did not use the formula it recently adopted to pass legislation against surprise billing: mandate that insurers and medical providers settle price differences via an outside arbitrator.

Senator Tina Smith, Democrat of Minnesota, proposed a bill in July that would cap coronavirus test reimbursement to twice the Medicare reimbursement rate. For rapid tests, that would be about $80.

In introducing her legislation, Senator Smith cited The Times’s reporting on high-priced tests as evidence for why such a change was needed.

“If these labs are going to take advantage of this situation, and charge whatever the market will bear, that pushes us into putting a limit on the cash price to stop the price gouging that is hurting consumers,” she said in an interview.

It’s unclear whether that legislation could become part of the reconciliation package that Congress is debating. There may be a hesitance to act: Legislators are tackling larger health care proposals, and they may expect the issue of testing fees to resolve on its own when the pandemic ends.

“Everyone keeps thinking we’re almost done, and this provision of the CARES Act only lasts as long as the public health emergency,” said Loren Adler, associate director of the U.S.C.-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy.

GS Labs plans to continue expanding, as demand for rapid testing remains robust. It does not see the Biden administration’s plan of widespread in-home rapid testing as an obstacle to its growth. It now operates 16 testing sites, and has plans to open two more soon. When those open, its cash price will remain the same.

“We’re very reasonable people, but our cash price is a true cash price for any insurer that does not want to negotiate,” Mr. Thompson of GS Labs said.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/26/upshot/cost-of-covid-rapid-test-prices.html