You Want Progressive Policies? You Need Progressive Taxes

Foolish federal dithering means states have to step in. Yes, even in the midst of a pandemic.

by By Kitty Richards and

As the coronavirus pandemic — and Congress’s undersize response — wreaks havoc throughout the economy, tax receipts are cratering. This means that state and local governments are facing enormous revenue shortfalls at the exact time they are dealing with large additional demands. So far, states and localities have responded by slashing spending and jobs, with 1.5 million public-sector workers laid off by the end of June.

The federal government, which unlike most states does not have to balance its budget every year, could solve the problem tomorrow by providing fiscal relief to states and localities, like the $1 trillion provided by the HEROES Act that passed the House in May.

But regardless of whether Congress acts, states and localities can bolster their local economies and support their residents by raising taxes on those who have not been hard hit by the recession. This is not only the right thing to do from a humanitarian standpoint, it is sound economics.

Spending cuts are enormously harmful to the people who rely on government services and the public workers who lose their jobs. In a recession, cuts also damage the broader economy, causing layoffs to ripple through the community.

When you fire a teacher, you harm her family and her. But you also harm the local grocery store where she shops, and all the other people and businesses she gives money to.

Using conservative estimates, these ripple effects mean that each dollar of spending the state cuts leads to a drop of at least $1.50 in the gross domestic product, and there are reasons to believe that the drop is as much as $2.50. With state budget shortfalls forecast to approach $300 billion this fiscal year, a spending-cut-only approach to balancing state budgets will cause at least a $450 billion reduction in G.D.P.— more than 2 percent.

Tax increases, especially on high-income people who aren’t living paycheck to paycheck, are much less economically damaging, costing the economy only around 35 cents for every dollar raised. States and localities that raise taxes on the rich to increase spending will create at least $1.15 of economic activity for every dollar raised, and most likely closer to $2.15 or more.

State and local spending never bounced back from the deep cuts made during the Great Recession, with devastating consequences for the U.S. economy. Had federal assistance enabled state and local spending to recover fully, the unemployment rate would have dropped to 4.4 percent in 2013, but instead we didn’t hit that level until 2017.

These spending cuts did not just reduce G.D.P., they left core state services underfunded. Take education. Just before the pandemic, public school systems had two million more students in kindergarten through 12th grade than before the Great Recession, and 77,000 fewer employees to teach them and run their schools. As of mid-May, public-sector layoffs had already surpassed their total for the entire Great Recession. With the school year still going, more than 750,000 K-12 education employees had already lost their jobs.

This at a time when education funding should be expanding. The Trump administration’s failure to control the pandemic has made it impossible in most places to safely open schools at current funding levels, but large budget increases to support smaller class sizes, building retrofits and other innovations could make it possible for kids to attend classes in person rather than on the computer. Instead, many districts are shuttering buildings and laying off teachers and other staff members.

This will have consequences for kids, families and our economy for years to come, and it is also stymying whatever recovery is possible: One in five out-of-work adults has stopped working because of the need to supervise online learning or care for younger children.

Some worry that state residents and businesses can’t afford a tax increase during the pandemic, but the truth is that many can, and it’s easy to target them through progressive taxation. Tens of millions of workers have lost their jobs since the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, but almost half of Americans report that their household has not lost any employment income at all, according to Census Bureau data. That figure jumps to two-thirds for households bringing home more than $200,000 per year.

The current situation is stacked on top of enormous existing inequality, with state and local tax policies that frequently ask the most of those least able to pay. The bottom 20 percent of earners pay, on average, a state and local effective tax rate more than 50 percent higher than that paid by the top one percent.

At the same time, state budget cuts fall disproportionately on those who are hardest hit by the pandemic. Black and Latino Americans have been infected with the coronavirus at three times the rate of whites, and died from the disease twice as often. They have also lost jobs and seen their incomes drop at a higher rate than white Americans, and they are disproportionately affected by public-sector layoffs.

Some will argue that states can’t raise taxes by themselves because of interstate competition, but economic evidence shows that even in boom times progressive state tax increases don’t harm state economies or lead rich people to flee. Now, with education and public health on the chopping block without higher taxes, moving to a low-tax, low-services state is likely to be still less appealing, even for the wealthy: States that institute ruthless cutbacks will prove to be far less attractive places to live.

Economic recovery will require more funding for state and local services. Some steps should be obvious: The 15 states that have not implemented Medicaid expansion, for example, could provide health insurance to millions of Americans, drawing billions of federal dollars into their local economies and over time reducing their overall spending out of local resources. All it would take is a willingness to cover 10 percent of the costs of expansion now.

Some problems will require creativity to solve. For instance, where normal schooling is unsafe, instead of laying off teachers and moving instruction online, school districts could hire more educators, repurpose empty office space and provide all students with the small, contained “learning pods” now favored by the wealthy.

Some states, and their voters, are taking bold action. Oklahoma and Missouri just voted to expand Medicaid by ballot initiative. Arizona voters will decide in November on an ambitious plan to raise more than $900 million a year for education through a 3.5 percent income tax surcharge on the top one percent of Arizonans.

The economic impact of the pandemic is daunting, and it would be better for the federal government to step in. But Americans are living through a catastrophe. They cannot afford for their state and local leaders to abdicate responsibility. States, cities and school districts must require their wealthiest residents to pay higher taxes right now.

The alternative is unacceptable: cutbacks in basic services that will weaken our social fabric and harm our potential for years to come, and a grinding recession that may last for years after the pandemic is brought under control.

Hospitals compete for money, not the people's health. We need to stop this.

by Joshua Freeman - Medicine and Social Justice blog - August 31, 2020

For decades, Santa Fe, NM, had only one hospital. St. Vincent’s was founded 155 years ago by the Sisters of Charity, but was taken over by the national Catholic corporation CHRISTUS in 2008. It’s a pretty good hospital with about 200 beds, for a small city of 85,000. A couple of years ago, the largest health system in New Mexico, Presbyterian, opened another hospital. It is a big building, but has only 30 beds, so its additional contribution is not primarily general inpatient care. Interestingly, while the hospital is on the far southwest side of Santa Fe, its main medical center building is directly across the street from St. Vincent’s. This is obviously not a coincidence, as it is now firmly in the center of the area in which people are accustomed to coming for medical care, establishing itself, at least for outpatient care, as a competitor.

The point that I want to talk about is not hospitals in Santa Fe specifically but rather competition among hospitals in general. This is not a problem in rural areas and small towns where the struggle is, rather, to hang on to their hospitals at all (often with just a very few inpatient beds, and almost invariably losing money). It may not be a big issue for mid-size cities like Santa Fe. It is a huge issue in the major metropolitan areas where most hospitals and doctors are, and where there are the greatest concentrations of patients (the medical term for what in English we call “people”).

In these areas, you will find that almost every big hospital

(or “medical center” or “health system”) has a Cancer Center. And a Heart

Center. Centers for Orthopedic Surgery and Sports Medicine are also big. And in

the last decade Neuroscience centers have joined the ranks of “must-haves” for

each of these centers. Of course, if they deliver babies, they certainly will

have a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. What is wrong with this? Are these not

important, serious diseases that can and do kill a lot of people and need

treatment? Am I advocating against treating, say, cancer?

Not at all. But while there are a lot of people with cancer, it is a finite number. Was the new Cancer Center just opened to a lot of hoopla at St. Elsewhere necessary because there were many cancer patients for whom there was not room in the Cancer Center at Downtown General, opened a few years ago, and now would have an opportunity to receive treatment? Or, just perhaps, is St. E’s hoping to attract many of the patients, and perhaps the doctors, who currently use DG to instead use their new, glitzy, state-of-the-art facility? Is it a simple matter of competition for a limited market?

If we had a medical care system that was based on the health care needs of the population, we wouldn’t have such redundancy of facilities; we would have enough for all the people who need care and not unnecessarily duplicate services. Downtown General might have centers of excellence in cancer and orthopedic sports medicine, while St. Elsewhere might be great for heart and neonatal care. And, since we are fantasizing about a system in which the driving force is the health of the people, let’s throw in primary care and mental health. But that doesn’t happen. And, in our hypothetical city, even with both cancer centers (and perhaps yet another at Doctors Medical Center), there will still be bunch of people who cannot receive care because they have no insurance or their insurance is poor (i.e., they are “underinsured”).

So, in addition to creating excess capacity, which creates major excess cost, competition in medical care services doesn’t meet the needs of all the people. The true driver of the health system, making money, creates at least three major sources of inequity:

- The services are only for the well-insured. Entire groups of poorly-insured people are excluded. The services offered by these special centers may be highly-profitable, but only if they get paid. They don’t make money providing care to poor or uninsured or underinsured people.

- The services offered are those that are highly profitable, and most often this is for particular procedures. Yes, cancer is bad. So is heart disease. But the real reason for these centers is that these conditions are very well reimbursed by insurers, so the hospitals (and doctors) make a lot of money (provided the patients meet criterion #1, of course). For example, while chemotherapy drugs are ridiculously expensive, of course, making money for the pharmaceutical industry, the hospital makes money on the “administration fees” which are far in excess of the actual cost of administration. In addition, the creation of new “centers” are often driven by a single procedure. No one had big “Neuroscience” centers until the procedure for inserting a catheter into a brain artery to pull out a clot was developed. THAT is reimbursed incredibly well! All of a sudden every big hospital needed a “Stroke Center” and started competing (and paying a lot of money for) “stroke doctors” (who might be neurologists, neurosurgeons, or invasive radiologists) who could do this procedure. But poorly reimbursed services? No matter how much the people need them, don’t expect lots of new centers for primary care. Or mental health. Or even general surgery. Essentially, we discriminate not only against those who are poor or uninsured, we discriminate against those who are unlucky enough to have poorly-reimbursed diseases!

- The third great inequity is obviously geographic. If you live in a major metropolitan area, and are well-insured, you can have your choice of which hospital is the best for your problem. You consult US News, ask your friends, read the ads. But if you are in a small town or rural area far from such a city, it’s a long trip. And not worth making if you don’t have the money.

What can and should we do? In the long term, we need to eliminate the motivation of hospitals to compete for profitable services by putting them on a global budget, which is what is done in Canada as part of their single-payer health care system, called (interestingly) Medicare. And, of course, we need to cover everyone so there are no people left out because they are poor and uninsured, a universal health insurance system, not “cover more” but “cover everybody”. And by long term, I mean as soon as possible.

In the mid-term, we must change policies to much less dramatically favor certain procedures at the expense of others. Pay more for mental health and primary care. Pay less for cancer drug administration and sucking clots out of brain arteries. Stop making it so much more profitable to do knee surgery than gall bladder surgery. The availability for any kind of procedure should be based on the need for it, not how well it is highly reimbursed. That is a totally backward motivation, and dangerous to our health. This can actually be done by federal policy simply by changing how (US) Medicare values and pays for services. Because Medicare is the largest payer, it sets the market rate. Private insurers may pay more, but it is always “multiples of Medicare”; the ratio of what is paid for one medical service relative to another is set by the federal government.

And while we’re at it, let’s eliminate the universal tax-breaks “non-profit” hospitals get for anything that they do, which are mostly things that will make them money! As evil in many other ways as for-profit hospitals are, they are at least required to pay taxes, and go to the capital markets for capital expansion. No donations to a hospital should be tax-deductible if they are going to be used for a money-making scheme. Again, in Canada capital budgets are separate from operating costs. A hospital is not motivated to increase its operating profit so it can expand and build, to better compete with others. It must apply for additional capital funds, which will only be available if they serve a health need.

In fact, this is something we can do in the near term. As citizens and donors, we can demand that the next opulent fund-raising gala for our local hospital is not for the purpose of expanding money-making services, but rather to expand those services to those who cannot currently access them. The money raised should be earmarked only for, say, providing cancer care at our great cancer center to uninsured people. That would be something for which tax-deductibility is justified.

It is outrageous that our health system in the US is structured to maximize money-making and not health. But as in so much else in our society, those making the money have a lot of it to use to exert their clout. It is going to take a massive national effort by the people to make the changes that we need to have.

https://medicinesocialjustice.blogspot.com/2020/08/hospitals-compete-for-money-not-peoples.html

Trump Program to Cover Uninsured Covid-19 Patients Falls Short of Promise

Some patients are still receiving staggering bills. Others don’t qualify because conditions other than Covid-19 were their primary diagnosis.

by Abby Goodnough - NYT - August 29, 2020

WASHINGTON — Marilyn Cortez, a retired cafeteria worker in Houston with no health insurance, spent much of July in the hospital with Covid-19. When she finally returned home, she received a $36,000 bill that compounded the stress of her illness.

Then someone from the hospital, Houston Methodist, called and told her not to worry — President Trump had paid it.

But then another bill arrived, for twice as much.

Ms. Cortez’s care is supposed to be covered under a program Mr. Trump announced this spring as the coronavirus pandemic was taking hold — a time when millions of people were losing their health insurance and the administration was doubling down on trying to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, the law that had expanded coverage to more than 20 million people.

“This should alleviate any concern uninsured Americans may have about seeking the coronavirus treatment,” Mr. Trump said in April about the program, which is supposed to cover testing and treatment for uninsured people with Covid-19, using money from the federal coronavirus relief package passed by Congress.

The program has drawn little attention since, but a review by The New York Times of payments made through it, as well as interviews with hospital executives, patients and health policy researchers who have examined the payments, suggest the quickly concocted plan has not lived up to its promise. It has caused confusion at participating hospitals, which in some cases have mistakenly billed patients like Ms. Cortez who should be covered by it. Few patients seem to know the program exists, so they don’t question the charges. And some hospitals and other medical providers have chosen not to participate in the program, which bars them from seeking any payment from patients whose bills they submit to it.

Large numbers of patients have also been disqualified because Covid-19 has to be the primary diagnosis for a case to be covered (unless the patient is pregnant). Since hospitalized Covid patients often have other serious medical conditions, many have other primary diagnoses. At Jackson Health in Miami, for example, only 60 percent of uninsured Covid-19 patients had decisively met the requirements to have their charges covered under the program as of late July, a spokeswoman said.

Critics say the stopgap program is among the strongest evidence that Mr. Trump and his party have no vision for improving health coverage, and instead promote piecemeal solutions, even in a national health crisis. Mr. Trump had promised a plan to replace the Affordable Care Act by the beginning of August, but none has been announced and he and other Republicans barely mentioned health policy in their national convention last week.

For now, as tens of thousands of new coronavirus cases are reported each day in the United States — and as Democrats eagerly frame the election as a referendum on Mr. Trump’s handling of the pandemic and his efforts to wipe out the health law in the Supreme Court — the Covid-19 Uninsured Program is his best offer.

“This is not the way you deal with uninsured people during a public health emergency,” said Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health law and policy at George Washington University.

Image

The program has clearly paid what, in many cases, would be staggering and unaffordable bills for thousands of Covid-19 patients. In addition to hospital care, it covers outpatient visits, ambulance rides, medical equipment, skilled nursing home care and even future Covid vaccines for the uninsured, “subject to available funding.” It does not cover prescriptions once patients leave the hospital, or treatment of underlying chronic conditions that make many more vulnerable to the virus.

Health care providers in all 50 states had been reimbursed a total of $851 million from the fund as of last week — $267 million for testing and $584 million for treatment— with hospitals in Texas and New Jersey receiving the most.

But the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan research organization, has estimated that hospital costs alone for uninsured coronavirus patients could reach between $13.9 billion and $41.8 billion, far more than what the program has paid out so far.

“The claims have just been so much smaller than anyone would have expected,” said Molly Smith, vice president for coverage and state issues forum at the American Hospital Association. “One thing we’ve heard a fair amount of is just serious backlogs and delays. But probably a lot of claims aren’t getting into the system at all because our members have determined they don’t qualify.”

The hospital association says that some hospitals have reported not submitting a substantial number of claims for their uninsured, with estimates ranging from 40 to 70 percent, because Covid-19 was not ruled their primary diagnosis.

“Either hospitals code inconsistent with ICD-10 rules,” said Tom Nickels, an executive vice president of the hospital association, referring to the diagnostic codes that hospitals use for billing, “or they don’t get paid even though the patient is clearly getting treated for Covid.”

Coronavirus Schools Briefing: The pandemic is upending education. Get the latest news and tips as students go back to school.

Harris Health, a two-hospital public system in Houston, did not bill the federal fund for 80 percent of the roughly 1,300 uninsured Covid-19 patients it had treated through mid-July because many of them also had other medical problems — most often, sepsis, an overwhelming reaction to infection that causes blood-pressure loss and organ failure. In other cases, “an underlying health condition was the primary reason for hospitalization, but was exacerbated by the Covid-19 disease,” Bryan McLeod, a spokesman, said.

Nationally, the total average charge for uninsured Covid- patients requiring a hospital stay is $73,300, according to FAIR Health, a health care cost database, although they may be able to negotiate a lower amount.

Reimbursements have varied widely with few obvious explanations; New Jersey providers, for example, have received $72 million in Covid treatment claims while those in neighboring New York have received half as much. Providers in hard-hit Texas and Florida, states that have not expanded Medicaid to cover more poor adults, have received $144 million and $53 million for treatment, respectively.

“It’s just not clear to me what’s going on,” said Jennifer Tolbert, director of state health reform at the Kaiser Family Foundation, who has looked closely at the program and its claims database.

Despite its limitations, some hospital executives said they liked the program because it paid Medicare rates, which are considerably higher than those for Medicaid, the government health insurance program for the poor, or any normal funding they would receive for charity care.

“This was a really progressive policy we were really surprised by, frankly,” said Dr. Shereef Elnahal, the chief executive of University Hospital in Newark, N.J., which has received $8.2 million for treating 787 uninsured patients with Covid, about a third of its coronavirus patients.

Unlike previous administrations during public health emergencies, Mr. Trump’s has not encouraged even temporary expansions of Medicaid — except for limited Covid testing — in states where the program covers few poor adults. It also declined to broadly reopen enrollment for Affordable Care Act plans once the pandemic began, although people who lose job-based coverage can enroll.

“You’re seeing a clash between enhancing Medicaid to allow it to cover the uninsured, versus providing a fixed amount of bailout money for providers who can figure out how to get to it,” Professor Rosenbaum said.

Gideon health care plan targets Big Pharma and Insurance, doesn’t include Medicare for All

by Alyce McFadden - Maine Beacon - August 31, 2020Calling access to affordable healthcare a “basic human right,” Maine House Speaker Sara Gideon last week unveiled her senate campaign’s health care agenda, which includes support for a public option but falls short of endorsing Medicare for All.

The agenda, announced Aug. 25, contains six broad categories for policy reform, including expanding access to rural healthcare, fighting the opioid crisis and protecting reproductive rights.

The Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act figures as a centerpiece and critical starting point for Gideon’s agenda. The plan is “Democratic orthodoxy,” as the Bangor Daily News put it, and aligns with many of the policies endorsed by other democratic candidates in races across the country, including Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden.

If implemented, the public option Gideon lays out would allow Americans to choose between buying into Medicare or remaining with their private insurer.

For Phil Caper, executive committee member of Maine AllCare, public option plans like the one Gideon proposes have the potential to help people afford critical medical care, and can even serve as a bridge to a single-payer system.

“It could be a step in the right direction, or it could also be a way to kick the can down the road,” Caper said

Reducing the cost of prescription drugs

Gideon’s agenda advocates for making “pay-for-delay” agreements between drug manufacturers illegal, a regulation that would bolster market competition and lower the cost of prescription drugs.

These controversial agreements occur when the manufacturer of a certain drug pays its competitors not to develop a lower-cost alternative medication. According to a Federal Trade Commission study, the practice costs American health care consumers $3.5 billion in extraneous health care costs each year.

Ann Woloson, executive director of Maine Consumers for Affordable Healthcare (MCAH), praised this provision of Gideon’s agenda and said if implemented, it would have a ripple effect on the general affordability of healthcare.

“The fact that she’s serious about getting rid of pay-for-delay means she’s serious about getting generic drugs to people sooner,” Woloson said. “And if people get the affordable medications they need sooner, it’s less likely they will need to be hospitalized, which would make healthcare generally less expensive.”

The agenda also proposes allowing Medicare to negotiate prescription drug prices, a reform that is extremely popular among Maine voters. An August memo by Data for Progress found that 70 percent of voters in Maine are more likely to cast their ballot for a candidate who supports legislation to allow Medicare to work with drug companies to lower prescription costs.

In general, Mainers on both sides of the aisle are likely to support a public option that negotiates prices with drug companies. According to a Data for Progress poll, 73 percent of surveyed voters reported they would support a candidate who endorsed a public insurance option that negotiates with drug companies to lower prices. A majority — 66 percent — of Republicans said they would also support such a proposal.

The reforms Gideon proposes would be a blow for pharmaceutical corporations and the agenda blames the drug industry’s political might and extensive lobbying efforts for establishing “the status quo of our healthcare system.”

“She’s serious about taking on tough issues and going against the pharma industry, which isn’t easy,” Woloson said.

Sen. Susan Collins has faced sharp criticism for accepting significant contributions from the pharmaceutical industry. Over the course of her career, Collins has taken hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations from industry-linked PACs and individuals, including from the Sackler family, owners of opioid makers Purdue Pharma, which has admitted to misleading the public about the dangers of Oxycontin, and from drug company Eli Lilly, which has dramatically hiked the price of insulin and faces a class action lawsuit for its alleged price gouging.

Contrasting records

Democrats have criticized Collins’ legislative record on health care policy.

Although Collins cast a deciding vote in 2017 to save the Affordable Care Act, that vote came after multiple votes to repeal the law. She later lent critical support for the Republican tax plan in December 2017 that fundamentally weakened the ACA. Health care advocates say that this vote set the stage for a legal argument that the entire program is unconstitutional.

“Gideon has provided more specificity than [Collins] has at least, and she’s been in office for what, 20 years?” Caper said.

From Woloson’s perspective, Gideon’s record in Augusta gives credence to her promises of reform.

“In our opinion, it is quite comprehensive and bold,” Woloson said of the agenda. “I think she is quite serious and sincere about doing what she can to improve access and affordability.”

In 2019, Gideon co-sponsored legislation with Rep. Troy Jackson (D-Allagash) to make it easier to import inexpensive generic drugs to Maine from Canada, a program she would look to expand on a federal level. Gideon and Jackson also passed a bill to create the Maine Prescription Drug Affordability Board to monitor and help regulate the cost of prescription drugs.

Gideon tenure as Speaker included the implementation of Maine’s expanded Medicaid program, which she support and which has provided health insurance for almost 60,000 Maine residents. Gov. Janet Mills completed the expansion mandated through a 2017 referendum when she took office in 2019.

Plan doesn’t ‘fix the foundation’

Gideon does not endorse Medicare for All or universal single-payer health care, the legislative solution backed by most progressive Democrats and introduced most recently in bills by Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wa.) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.).

Universal health care program is broadly popular among Maine Democratic voters—a CNN exit poll of voters in the Democratic primary in March found that 69 percent supported the program.

Gideon’s more moderate public option plan places her on the right of Maine’s congressional representatives, Rep. Jared Golden and Rep. Chellie Pingree, who both co-sponsored Jayapal’s house bill in 2019.

Another candidate for the senate seat, Green Independent Lisa Savage, has made Medicare for All a central plank of her campaign.

“What was already a simmering healthcare crisis has been brought to a rolling boil by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Savage in a statement this April. “The pandemic has exposed the crisis in the U.S. healthcare system and the urgent need for an improved Medicare for All health insurance system to ensure that all U.S. residents are able to get medical care when they get sick, with no exceptions.”

For Caper, Gideon’s plan is “incrementalist.” It makes positive changes to a broken system, but does not change the system’s overall structure.

“It’s like you have a house that’s slowly sinking into mud because the foundation is rotting,” Caper said. “No matter what you do to the house itself, it’s not going to solve the problem unless you fix the foundation.”

The public option — which would exist alongside for-profit private insurance companies and healthcare providers — would be like fixing the house and ignoring the foundation, according to Caper.

“We have to have a fundamentally different health care system, which means turning it into a public good rather than a commodity,” Caper said.

Prognosis for Rural Hospitals Worsens With Pandemic

by Sarah Jane Tribble - Kaiser Health News - August 26, 2020

Jerome Antone said he is one of the lucky ones.

After becoming ill with COVID-19, Antone was hospitalized only 65 miles away from his small Alabama town. He is the mayor of Georgiana — population 1,700.

“It hit our rural community so rabid,” Antone said. The town’s hospital closed last year. If hospitals in nearby communities don’t have beds available, “you may have to go four or five hours away.”

As COVID-19 continues to spread, an increasing number of rural communities find themselves without their hospital or on the brink of losing already cash-strapped facilities.

Eighteen rural hospitals closed last year and the first three months of 2020 were “really big months,” said Mark Holmes, director of the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Many of the losses are in Southern states like Florida and Texas. More than 170 rural hospitals have closed nationwide since 2005, according to data collected by the Sheps Center.

It’s a dangerous scenario. “We know that a closure leads to higher mortality pretty quickly” among the populations served, said Holmes, who is also a professor at UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. “That’s pretty clear.”

One 2019 study found that death rates in the surrounding communities increase nearly 6% after a rural hospital closes — and that’s when there’s not a pandemic.

Add to that what is known about the coronavirus: People who are obese or live with diabetes, hypertension, asthma and other underlying health issues are more susceptible to COVID-19. Rural areas tend to have higher rates of these conditions. And rural residents are more likely to be older, sicker and poorer than those in urban areas. All this leaves rural communities particularly vulnerable to the coronavirus.

Congress approved billions in federal relief funds for health care providers. Initially, federal officials based what a hospital would get on its Medicare payments, but by late April they heeded criticism and carved out funds for rural hospitals and COVID-19 hot spots. Rural hospitals leapt at the chance to shore up already-negative budgets and prepare for the pandemic.

The funds “helped rural hospitals with the immediate storm,” said Dr. Don Williamson, president of the Alabama Hospital Association. Nearly 80% of Alabama’s rural hospitals began the year with negative balance sheets and about eight days’ worth of cash on hand.

Before the pandemic hit this year, hundreds of rural hospitals “were just trying to keep their doors open,” said Maggie Elehwany, vice president of government affairs with the National Rural Health Association. Then, an estimated 70% of their income stopped as patients avoided the emergency room, doctor’s appointments and elective surgeries.

“It was devastating,” Elehwany said.

Paul Taylor, chief executive of a 25-bed critical access hospital and outpatient clinics in northwestern Arkansas, accepted millions in grants and loan money Congress approved this spring, largely through the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act.

“For us, this was survival money and we spent it already,” Taylor said. With those funds, Ozarks Community Hospital increased surge capacity, expanding from 25 beds to 50 beds, adding negative pressure rooms and buying six ventilators. Taylor also ramped up COVID-19 testing at his hospital and clinics, located near some meat-processing plants.

Throughout June and July, Ozarks tested 1,000 patients a day and reported a 20% positive rate. The rate dropped to 16.9% in late July. But patients continue to avoid routine care.

Taylor said revenue is still constrained and he does not know how he will pay back $8 million that he borrowed from Medicare. The program allowed hospitals to borrow against future payments from the federal government, but stipulated that repayment would begin within 120 days.

For Taylor, this seems impossible. Medicare makes up 40% of Ozarks’ income. And he has to pay the loan back before he gets any more payments from Medicare. He’s hoping to refinance the hospital’s mortgage.

“If I get no relief and they take the money … we won’t still be open,” Taylor said. Ozarks provides 625 jobs and serves an area with a population of about 75,000.

There are 1,300 small critical access hospitals like Ozarks in rural America and, of those, 859 took advantage of the Medicare loans, sending about $3.1 billion into the local communities. But many rural communities have not yet experienced a surge in coronavirus cases — national leaders fear it will come as part of a new phase.

“There are pockets of rural America who say, ‘We haven’t seen a single COVID patient yet and we do not believe it’s real,’” Taylor said. “They will get hit sooner or later.”

Across the country, the loss of patients and increased spending required to fight and prepare for the coronavirus was “like a knife cutting into a hospital’s blood supply,” said Ge Bai, associate professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Bai said the way the federal government reimbursed small rural hospitals through federal programs like Medicare before the pandemic was faulty and inefficient. “They are too weak to survive,” she said.

In rural Texas about two hours from Dallas, Titus Regional Medical Center chief executive Terry Scoggin cut staff and furloughed workers even as his rural hospital faced down the pandemic. Titus Regional lost about $4 million last fiscal year and broke even each of the three years before that.

Scoggin said he did not cut from his clinical staff, though. Titus is now facing its second surge of the virus in the community. “The last seven days, we’ve been testing 30% positive,” he said, including the case of his father, who contracted it at a nursing home and survived.

“It’s personal and this is real,” Scoggin said. “You know the people who are infected. You know the people who are passing away.”

Of his roughly 700 employees, 48 have tested positive for the virus and one has died. They are short on testing kits, medication and supplies.

“Right now the staff is strained,” Scoggin said. “I’ve been blown away by their selflessness and unbelievable spirit. We’re resilient, we’re nimble, and we will make it. We don’t have a choice.”

https://khn.org/news/rural-hospital-closures-worsen-with-pandemic/

Column: Trump hasn’t done anything to bring down drug costs. You’re paying the price

by Michael Hiltzik - LA Times - August 31, 2020

If the Republican National Convention is any guide, you’re going to be hearing a lot in the next two months about how President Trump has brought down drug prices.

“Now, I’m really doing it,” Trump said on Day 1 of the RNC last week.

It wasn’t the first time he patted himself on the back for fighting Big Pharma.

“Drug prices are coming down, first time in 51 years because of my administration,” he said in May 2019.

None of this is true, as has been pointed out in recent days by economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Kevin Drum of Mother Jones, and over the longer term by hard data compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Drug prices are coming down, first time in 51 years because of my administration.

President Trump, lying about his work on drug prices

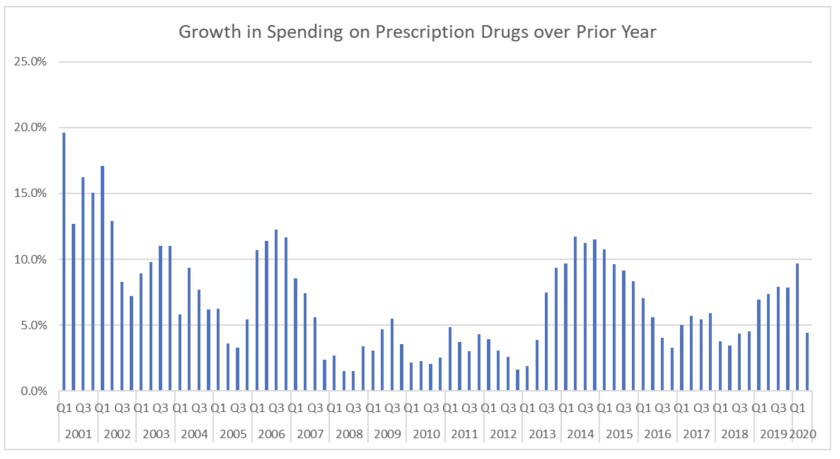

The truth is that prescription drug spending in the U.S. has risen almost inexorably throughout Trump’s term, generally at a faster pace than during President Obama’s first term and toward the end of his second term.

The pace of increase dropped sharply in the second quarter this year ended June 30, but that’s an artifact of the pandemic, during which many Americans have deferred routine doctor visits. But drug spending increased nevertheless, by 4.1% over the same quarter a year ago.

Prescription drug spending reached an annual rate of $497.8 billion in the first quarter, up by about 21.7% from the $409.1-billion annual rate in the first quarter of 2017, the start of the Trump presidency.

In sum, Trump hasn’t done anything to rein in drug prices. He has obscured that fact with his usual miasma of misrepresentation and misstatements, abetted by a drug industry that has been happy to go along with the subterfuge.

No one should be surprised at the lack of progress.

Trump’s secretary of health and human services, Alex Azar, is a former lobbyist for the drug company Eli Lilly and a former president of its U.S. operations. During his tenure at Lilly, the company tripled the price of its top-selling insulin product and was fined by Mexico for colluding to fix prices that the government paid for insulin.

Let’s start with Trump’s most recent claim, and work backward.

Trump’s convention reference was to a sheaf of executive orders he signed July 24.

One of the four orders would forbid drug company rebates on drugs for Medicare members to go to pharmacy benefit managers or health plans that negotiate discounts. Instead, the rebates would have to be passed on to the enrollees themselves.

The problem with such a rule, the Congressional Budget Office has pointed out, is that it would drive Medicare premiums higher.

For many members, especially those who use few prescriptions or drugs without large rebates, the increase in premiums would outstrip the savings from the rule. In other words, the rule would impose higher costs on members and on the federal government, which subsidizes Medicare premiums.

Trump’s executive order mandates that implementing the rule can’t increase federal spending, Medicare premiums or total out-of-pocket costs. But that just means the rule would be impossible to implement.

A second order would require government-sponsored dispensaries, generally in rural areas, to make insulin and epinephrine available to low-income patients without health insurance or with high co-pays. But those dispensaries already offer those drugs effectively for free to patients under the poverty line, so the rule’s impact would be minimal.

A third order would allow more Americans to import drugs from Canada, where the prices on many pharmaceuticals are lower than in the U.S. But there’s no guarantee that American buyers can access those lower prices, since Canada and the drug companies have made clear they’ll take steps to protect their own markets.

Then there’s the fourth order, which Trump called “the granddaddy of them all.”

It’s also the murkiest. Purportedly, it would tie Medicare prices for certain drugs to the best prices obtained in some foreign countries, a concept known as most-favored-nation status. But the rule would apply only to drugs administered in doctors’ offices, such as intravenous cancer drugs, not to prescription drugs bought from a pharmacy.

The full text of this order hasn’t been released. Trump originally said he would hold it back until Aug. 24 to give Big Pharma a chance to stave it off by coming up with “something that will substantially reduce drug prices.”

He said he had scheduled a meeting with drug executives for July 28 to hear their views, but that never happened. As my colleague David Lazarus reported on the deadline day, the industry eventually came up with a counter-offer to cut Medicare prices on some doctor-administered drugs by 10%. This wouldn’t even qualify as a “modest proposal.”

The rate of growth in prescription spending has picked up since Trump took office.

(Center for Economic and Policy Research)

Basically, then, Trump’s trumpeted executive orders amounted to a smidgen more than nothing. That extended the pattern of Trump action on drug prices seen from the inception.

It will be remembered that Trump launched his drive on drug prices in 2018 by ostensibly jawboning Big Pharma into rolling back price hikes imposed as of July 1. “Great news for the American people,” he crowed on Twitter.

Sadly, no. As we observed at the time, this was nothing but a sop to Trump. The giant drug company Pfizer, for example, made clear that it wasn’t “rolling back” any increases — it was “deferring” them — temporarily.

“The company will return these prices to their pre-July 1 levels as soon as technically possible,” the company said.

Merck, to take another example, said it would lower the price of its hepatitis C treatment Zepatier by 60% and cut prices on six other drugs by 10%. Merck also pledged to not increase the average net price of its overall product portfolio by more than the inflation rate annually.

This was another head-fake. Zepatier was an also-ran among hepatitis C cures, with sales so low by the first quarter of 2018 that Merck listed its U.S. sales in its quarterly disclosures as zero. The other six drugs faced stiff competition from generic versions, and by some estimates accounted for less than 0.1% of Merck’s $40 billion in annual sales.

Merck’s pledge to hold the average net price of its portfolio to the inflation rate opened the door to its imposing steep price hikes on the drugs that mattered to its bottom line, while cutting prices on drugs that didn’t matter.

Anyway, as soon as everyone’s attention shifted elsewhere, the drug companies rolled back the “rollbacks.” By December, Pfizer and Merck said they were moving ahead with price increases.

While this was going on, Trump, Big Pharma and Senate Republicans were stifling a proposal that really could have achieved something. This was a measure sponsored by House Democrats in 2019 and named after Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.), a long-term foe of high drug prices.

The measure would require Medicare to negotiate prices for at least 25 of the most-prescribed drugs every year, starting in 2021, for Part D, the Medicare prescription program. The target drugs would be drawn from the list of 125 drugs with the highest spending in Part D and the commercial market.

The negotiated price couldn’t be higher than 120% of the average cost for the given drug in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom. Most critically, the proposal would impose a stiff excise tax of as much as 95% on companies that refused to negotiate. That would keep them at the table.

Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) declared the bill dead on arrival. “Socialist price controls will do a lot of left-wing damage to the healthcare system,” he said.

See how this works? Trump and the GOP are all-in on proposals that aren’t serious and won’t work, but erect a brick wall against those with potential.

The result is that the drug industry sits back as the money rolls in, at your expense. Economist Baker observes that spending on prescription drugs actually increased “somewhat more rapidly under Trump than Obama-Biden, rising at a 6.3% annual rate under Trump compared to a 5.5% rate under Obama-Biden.” (He didn’t count the most recent quarter, affected by the pandemic.)

That won’t keep Trump from continuing to claim that he has held Big Pharma to account. But it should keep you from believing him.

No comments:

Post a Comment