Editor's Note:

The following four articles represent a debate among the proponents of universal health care about the policies and tactics most likely to achieve our common goal. They are worth the time it will take of all advocates for universal healthcare in the US to read and understand them, and to familiarize ourselves with the differing perspectives of all universal healthcare advocates.

"Single Payer" is finally receiving the thought and discussion it deserves, as a serious policy option for the U.S. We should all be prepared to react to all of the arguments expressed in the clippings that follow. We will be hearing a lot about them as we continue the drive toward health care for all.

- SPC

Medicare-for-All Isn’t the Solution for Universal Health Care

by Joshua Holland - The Nation - August 2, 2017

Within the broad Democratic coalition, it’s pretty clear that the discussion of health care has shifted to the left. Mainstream figures like Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, a potential presidential candidate in 2020, are embracing single payer. Representative John Conyers’s Medicare-for-All bill currently has 115 Democratic co-sponsors in the House. And Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer recently said that single payer is now “on the table.” Assuming we have free and fair elections in the future, and Democrats regain power at some point, this is all very good news for single-payer advocates.

But that momentum is tempered by the fact that the activist left, which has a ton of energy at the moment, has for the most part failed to grapple with the difficulties of transitioning to a single-payer system. A common view is that since every other advanced country has a single-payer system, and the advantages of these schemes are pretty clear, the only real obstacles are a lack of imagination, or feckless Democrats and their donors. But the reality is more complicated.

For one thing, a near-consensus has developed around using Medicare to achieve single-payer health care, but Medicare isn’t a single-payer system in the sense that people usually think of it. This year, around a third of all enrollees purchased a private plan under the Medicare Advantage program. These private policies have grown in popularity every year, in part because the field has been tilted against the traditional, government-run program. Medicare Advantage plans must have a cap on out-of-pocket costs, for example, while the public program does not. Around one-in-four Medicare enrollees also purchase some sort of “Medigap” policy to cover out-of-pocket costs and stuff that the program doesn’t cover, and then there are both public and private prescription drug plans.

The array of options can be bewildering—it’s a far cry from the simplicity that single-payer systems promise.

At the same time, Medicare-for-All is really smart politics. Medicare is not only popular, it’s also familiar. Many of us have parents or grandparents who are enrolled in the program. And polls show that a significant majority of Americans now believe that it’s the government’s “responsibility to provide health coverage for all.”

But from a policy standpoint, Medicare-for-All is probably the hardest way to get there. In fact, a number of experts who tout the benefits of single-payer systems say that the Medicare-for-All proposals currently on the table may be virtually impossible to enact. The timing alone would cause serious shocks to the system. Conyers’s House bill would move almost everyone in the country into Medicare within a single year. We don’t know exactly what Bernie Sanders will propose in the Senate, but his 2013 “American Health Security Act” had a two-year transition period. Radically restructuring a sixth of the economy in such short order would be like trying to stop a cruise ship on a dime.

Harold Pollack, a University of Chicago public-health researcher and liberal advocate for universal coverage, says, “There has not yet been a detailed single-payer bill that’s laid out the transitional issues about how to get from here to there. We’ve never actually seen that. Even if you believe everything people say about the cost savings that would result, there are still so many detailed questions about how we should finance this, how we can deal with the shock to the system, and so on.”

Achieving universal coverage—good coverage, not just “access” to emergency-room care—is a winnable fight if we sweat the details in a serious way. If we don’t, we’re just setting ourselves up for failure.

Centrist Democrats will no doubt be one obstacle to universal coverage, but a more fundamental problem is that compelling the entire population to move into Medicare, especially over a relatively short period of time, would invite a massive backlash.

The most important takeaway from recent efforts to reshape our health-care system is that “loss aversion” is probably the central force in health-care politics. That’s the well-established tendency of people to value something they have far more than they might value whatever they might gain if they give it up. This is one big reason that Democrats were shellacked after passing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, and Republicans are now learning the hard way that this fear of loss cuts both ways.

“Remember how much trouble President Obama got into when he said that if you like your insurance you can keep it?” asks Pollack. “For something like 1.6 million people, that promise turned out to be hard to keep. And that created a firestorm.” Those 1.6 million people represented less than 1 percent of the non-elderly population, and most of them lost substandard McPlans which left them vulnerable if they got sick. The ACA extended coverage to almost 10 times as many people, but those who lost their policies nonetheless became the centerpiece of the right’s assault on the law. Trump and other Republicans are still talking about these “victims” of Obamacare to this day.

Under the current Medicare-for-All proposals, we would be forcing over 70 percent of the adult population—including tens of millions of people who have decent coverage from their employer or their union, or the Veteran’s Administration, or the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program—to give up their current insurance for Medicare. Many employer-provided policies cover more than Medicare does, so a lot of people would objectively lose out in the deal.

Some large companies skip the middle man and self-insure their employees—and many offer strong benefits. We’d be killing that form of coverage. If we were to turn Medicare into a single-payer program, as some advocates envision, then we’d also be asking a third of all seniors to give up the heavily subsidized Medicare Advantage plans that they chose to purchase. Consider the political ramifications of that move alone. And because some doctors would decline to participate in a single-payer scheme, which would come with a pay cut for many of them under Medicare reimbursement rates, we couldn’t even promise that if you like your physician you can keep seeing him or her.

Don’t be lulled into complacency by polls purporting to show that single payer is popular—forcing people to move into a new system is all but guaranteed to result in tons of resistance. And that’s not even considering the inevitable attacks from a conservative message machine that turned a little bit of money for voluntary end-of-life counseling into “death panels.” Public opinion is dubious given that nobody’s talking about the difficulties inherent in making such a transition.

It’s true that every other developed country has a universal health-care system, and we should too. But make no mistake: Moving the United States to national health care would be unprecedented, simply because we spend more on this sector than any other country ever has.

“For the most part, these countries were spending maybe 2 or 3 percent of [their economic output] on health care when they set up these systems after World War II,” says Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “Most of them are spending 8 or 9 or maybe 10 percent of their [output] now, and this is 70 years later.”

In 2015, the United States spent 17.8 percent of its output on health care. The highest share ever for an advanced country establishing a universal system was the 9.2 percent that Switzerland spent in 1996, and they set up an Obamacare-like system of heavily regulated and subsidized private insurance. (They also spend more on health care today than anyone but us.)

There’s a common perception that because single-payer systems cost so much less than ours, passing such a scheme here would bring our spending in line with what the rest of the developed world shells out. But while there would be some savings on administrative costs, this gets the causal relationship wrong. Everyone else established their systems when they weren’t spending a lot on health care, and then kept prices down through aggressive cost-controls.

“Bringing costs down is a lot harder than starting low and keeping them from getting high,” says Baker. “We do waste money on [private] insurance, but we also pay basically twice as much for everything. We pay twice as much to doctors. Would single-payer get our doctors to accept half as much in wages? It could, but they won’t go there without a fight. This is a very powerful group. We have 900,000 doctors, all of whom are in the top 2 percent, and many are in the top 1 percent. We pay about twice as much for prescription drugs as other countries. Medical equipment, the whole list. You could get those costs down, but that’s not done magically by saying we’re switching to single payer. You’re going to have fights with all of these powerful interest groups.”

Baker is himself a single-payer advocate, and he’s worked with various groups that advocate for it, but, he says, “I don’t think you can get there overnight. I think you have to talk about doing it piecemeal, step-by-step.”

Single-payer advocates are mostly right about its benefits. These systems are simpler, they cut down on administrative costs, and they cover everyone.

But the term “single-payer” is itself misleading. The truth is that many of the systems we refer to as single-payer are a lot more complicated than we tend to think they are. Canada, for example, finances basic health care through six provincial payers. Its Medicare system provides good, basic coverage, but around two in three Canadians purchase supplemental insurance because it doesn’t cover things like prescription drugs, dental health, or vision care. About 30 percent of all Canadian health care is financed through the private sector.

Most countries have mixed funding schemes that vary in complexity, and the term “single-payer” may be giving some people a false promise. Conyers’s Medicare-for-All bill promises to cover virtually everything while banishing out-of-pocket costs, but no other health-care system offers such expansive benefits. Even people living in Scandinavian social democracies face out-of-pocket expenses: In 2015, the most recent year for OECD data, the Swedes covered 15 percent of their health costs out-of-pocket; in Norway, it was 14 percent and the Finns shelled out 20 percent out-of-pocket.

Most countries with “single-payer” systems rely on some combination of public insurance, various mixes of mandatory and voluntary private insurance (usually tightly regulated), and out-of-pocket expenditures (often with a cap). They offer free coverage for those who can’t afford it, but the exact benefits vary from country-to-country.

Germany’s “single-payer” system has 124 not-for-profit insurers participating in one national exchange. About 10 percent of Germans—the wealthiest ones—opt out of the national system and go fully private, and most of them buy plans from for-profit insurers.

The Dutch system is somewhat like Obamacare in that everyone must purchase insurance for basic services from private insurers. But the similarities end there: Insurers are barred from distributing profits to their shareholders, and a separate, entirely public scheme covers long-term care and other costly services. Premiums are subsidized, but most Dutch people purchase supplemental insurance to cover things like dental care, alternative medicine, contraceptives, and their co-payments.

The French system is often cited as the best in the world, and about a quarter of it is financed through the private sector. The French are mostly covered through nonprofit insurers in a single national pool, but most working people get their policies through their employers. Almost all French citizens either purchase government vouchers to cover things like vision and dental care, or are provided with them gratis if necessary. The system is financed through a complicated mix of general revenues, employer contributions, payroll taxes and taxes on drugs, tobacco, and alcohol.

So the United States isn’t unique because it uses a mix of public and private financing—the big difference, as these OECD data show, is that we rely much more heavily on private insurance than any other wealthy country.

Understanding that other countries’ schemes vary significantly in the details—and that in the United States, the cost of care would remain a serious challenge under any system—should lead to a different conversation among progressives. Rather than making Medicare-for-All a litmus test, we should start from the broader principle that comprehensive health care is a human right that should be guaranteed by the government—make that the litmus test—and then have an open debate about how best to get there. Maybe Medicaid is a better vehicle. Perhaps a long phase-in period to Medicare-for-All might help minimize the inevitable shocks. There are lots of ways to skin this cat.

At a minimum, it’s time to get past the idea that anyone who doesn’t embrace Medicare-for-All, as it’s currently defined, must be some kind of neoliberal hack.

An obvious alternative to moving everyone into Medicare is to simply open up the program and allow individuals and employers to buy into it. We could then subsidize the premiums on a sliding scale. But recent experience with the ACA suggests that this kind of voluntary buy-in won’t cover everyone, or spread out the risk over the entire population.

There are other alternatives, one of which was a popular progressive scheme before Barack Obama tried to tackle health care.

Progressive critics of the ACA are partially correct when they say that Democrats passed a plan that looked similar to “Romneycare” in Massachusetts. In the end, it was at least structurally similar to a scheme originally cooked up by the Heritage Foundation, thanks to a handful of Democrats—led by then-Senator Joseph Lieberman—who killed the public option.

But the sausage-making began well to the left of anything Heritage would ever countenance, modeled in part on Yale political scientist Jacob Hacker’s “Health Care for America” proposal. It would have left employment-based insurance—and Medicare coverage for the elderly—intact, and created a large new Medicare-like public insurance program that would have been far more robust than anything contemplated during the development of the ACA.

Hacker still thinks that, in broad terms, this is the best approach. He calls it “Medicare for More,” and hopes that it would do a better job at containing costs than employer-based insurance. Then, by creating a kind of virtuous cycle, there would be more buy-ins which would ultimately lead to “Medicare for Most.”

“In other countries, you’re basically guaranteed coverage and then they figure out how to pay for it,” he says. “Some of that money may come from you, some will come from your employer and some of it will come from general funds. We don’t have that approach. People who don’t have coverage from their employers have to figure out how to sign up—either for Medicaid, or through the exchanges. Yes, we have a penalty to encourage people to do that, but they still have to navigate this incredibly complex system.”

With Hacker’s program, perhaps to be called Medicare Part E, employers would have a choice of providing their employees with coverage as good as they would get in this big public insurance pool, or buying into the scheme. Premiums would vary based on workers’ incomes.

Hacker says he has various ideas for bringing people who aren’t attached to the labor force into the system. One possibility would be to automatically enroll everyone at birth, and cover them until they have a choice of switching to an employer-based plan. Call it Medicare-for-All-Who-Need-It.

“While the savings would be larger if everyone participated in a single pool, they’d still be significant,” says Hacker.

And maybe there’s a better way still that hasn’t yet been discussed. The fight for a universal health-care system in the United States is now in its 105th year, and if we don’t admit that financing any kind of universal system is going to be especially difficult given how much we spend, or acknowledge the role that loss aversion plays in the politics of reform, then we’re going to fail again the next time we get a shot at it.

Above all, progressives need to learn something from the Republicans’ effort to replace the ACA. They promised that facile slogans like “freedom” and “choice” would magically increase coverage and bring down costs. They were selling snake oil, and one way or the other, it’s going to come back and bite them.

We shouldn’t make promises that we aren’t going to be able to keep. “It’s not going to be easy to do,” Jacob Hacker says, “and anyone who tells you that the most expensive health-care system in the world is going to undergo a sudden shift to highly efficient and low-price medicine has not been studying American medicine.”

Can Medicare for All Succeed?

by Steffie Woolhandler and David U. Himmelstein - The Nation - August 16, 2017

Joshua Holland’s anti–single payer screed (“Medicare for All Isn’t the Solution for Universal Health Care”) is so riddled with misinformation and outright errors that it makes one wonder whether The Nation has laid off its fact-checkers.

Just one example: In arguing the impossibility of a health-care transformation in a high-spending nation, Holland claims that Switzerland’s health expenditures in 1996 amounted to only 5 percent of GDP. The correct figure is 9.2 percent. [Editor’s Note: This has been corrected in Holland’s article.]

He suggests that cost control under single payer requires halving doctors’ incomes, a serious political problem if it were true. But Canadian doctors make about 80 percent what their US counterparts do, and, taking into account their lower educational debt and post-retirement health expenses (more than $250,000 per couple in the United States), they’re about as well off financially as their US counterparts. Moreover, most US single-payer projections foresee increased spending on physician visits once copayments are abolished, and simplified billing would reduce the bite that office overhead takes out of doctors’ take-home pay.

Holland falsely claims that no one has provided guidance on the transition to single payer. We, and our colleagues in Physicians for a National Program have published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, The American Journal of Public Health, and the New England Journal of Medicine several quite detailed proposals laying out transition plans for acute-care financing, long-term care, and quality monitoring; another, on prescription-drug regulation and financing, is in the works. We’ve analyzed in detail the likely shifts in administrative costs and employment, and the federal single-payer legislative proposals include funding for job retraining and placement and income support to transition the million or so insurance and administrative workers who currently do useless bureaucratic work and whose jobs would be eliminated under single payer. While the transition would be disruptive for some administrative workers, it would be simple for hospitals (they’d stop billing for each patient, Band-Aid, and aspirin tablet and instead be paid lump-sum budgets), and a welcome relief for doctors and nurses, who suffer record high burnout rates in the current medical-industrial complex. That’s why recent polls show that around half of doctors favor single payer (and 21,000 of them have joined Physicians for a National Health Program), and National Nurses United, the leading nurses’ union, is the nation’s strongest single-payer proponent.

Most egregiously, Holland misrepresents the single-payer legislation that’s actually been proposed, citing Medicare’s deficiencies to smear reform proposals. As the title of John Conyers’s bill HR676, the Expanded & Improved Medicare for All Act, makes clear, that legislation would upgrade Medicare coverage, eliminating copayments and deductibles, and fix its other flaws. Holland suggests that, since many Medicare recipients supplement their coverage with private policies, such legislation would boost out-of-pocket costs for millions who currently have employer-paid coverage or Medigap policies. In fact, virtually no one would face increased copayments or deductibles under HR 676 (or Bernie Sanders’s forthcoming legislation, or the many state bills), although wealthy Americans’ taxes would rise. And few people would complain about being freed from insurers’ narrow provider networks; not one of the Medicare Advantage plans, without out-of-pocket benefits, covers care at New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Under single payer patients could, as in Canada, choose any hospital or doctor.

Holland’s scare-mongering about the chaos likely to ensue during a transition to single payer echoes The Wall Street Journal’s dire predictions of “patient pileups” and other disasters at the dawn of Medicare in 1965. It didn’t happen then and wouldn’t happen now. Medicare, sans computers, enrolled 18.9 million seniors (displacing private insurance for many of them) within 11 months of its passage.

The real enemies of single payer aren’t the disgruntled patients or doctors whom Holland features but the insurance and pharmaceutical firms that he barely mentions. That powerful opposition is the real problem we have to overcome, not the imagined chaos of the transition or the phony fear that patients would revolt against better coverage.

JOSHUA HOLLAND REPLIES

Himmelstein and Woolhandler aren’t alone in accusing me of dishonestly failing to note that Representative John Conyers’s Medicare-for-All bill would “fix” the current program’s “flaws,” including the fact that Medicare is not currently structured as a single-payer program. But I wrote quite clearly that, “if we were to turn Medicare into a single-payer program, as some advocates envision, then we’d also be asking a third of all seniors to give up the heavily subsidized Medicare Advantage plans that they chose to purchase. Consider the political ramifications of that move alone.”

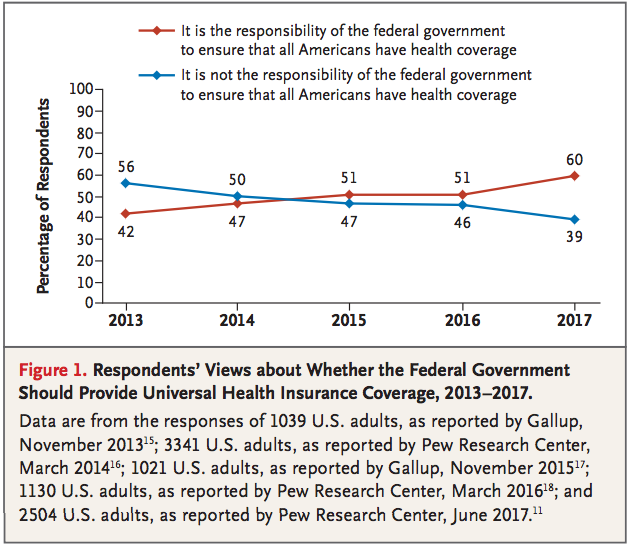

Like other critics, Ida Hellander simply wishes away what I see as the central issue of loss aversion, citing a 2009 blog post by Kip Sullivan which asserts that “two-thirds of Americans support Medicare-for-all.” Sullivan cites a number of conflicting polls conducted in the early 2000s. We have more recent indications of how the American public feels about government involvement in health-care provision now, seven years after the Affordable Care Act was enacted: Pew’s oft-cited poll from June of this year found that, while a record high 60 percent of respondents say that it’s the government’s responsibility to cover everyone, only 33 percent said that should be accomplished through a “single national government program,” and the remainder offered that it should be done through a mix of public and private programs or were unsure.

Loss aversion is a very well documented phenomenon, and it is entirely irrational. In one famous study, one set of participants were given $50 and offered a choice between keeping $30 or taking a 50/50 all-or-nothing bet. Another group were offered the same terms, but this time the choice was phrased as losing $20 or taking the bet. Just changing the wording from “keeping $30” to “losing $20” resulted in a significant increase in those willing to roll the dice—such is our distaste for losing something we have.

Status-quo bias is another very real, and not entirely rational phenomenon—people tend to wary of change, especially sudden or radical change. And of course, the next debate over health-care reform won’t be conducted honestly, as we’ve seen from the opposition to the Affordable Care Act. It’s telling in that arguing that “implementation is the easy part of health reform,” Dr. Hellander cites the experience of Taiwan, which in 1994 was a country of 21 million that was still transitioning from a military dictatorship and spent 5 percent of its GDP on health care.

Unfortunately, these writers and other critics confirm my worry that a single, extremely difficult route to universal coverage is fast becoming a litmus test for progressives. All have attempted to excommunicate me from the left, framing my piece as part of an attack, perhaps a concerted one, on single payer by “liberal” opponents. The reality is that I have long been, and will continue to be, an advocate of establishing a universal health-care system that might be called “single payer.” But I continue to think that rapidly moving much of the population into a single program—without first either creating a model at the state level or delivering some tangible benefits through more modest Medicare expansions—is a recipe for failure.

To the editors:

Liberals have created a new single-payer bogeyman to justify their renewed pursuit of failed incremental policies for health reform, as in Joshua Holland’s recent article. It used to be that single payer was not “politically feasible.” Now, according to the likes of Holland, Harold Pollack, and Dean Baker, the problem is that single-payer advocates haven’t worked out a plan to “implement” single payer, or the “brass tacks.”

In fact, implementation is the easy part of health reform. The Canada Health Act is less than 14 pages long, and is only that long because it is also printed in French. Taiwan, which had 40 percent of its population uninsured, installed a universal single-payer system ahead of schedule in less than a year in 1995. The ease of adoption of the American Medicare program also bodes well for single payer, as Holland admits. Indeed, nearly every implementation issue Holland raises is already addressed in the Physicians Proposal for Single Payer National Health Insurance (2015) and Representative John Conyers’s bill, HR 676, the “gold standard” for single-payer legislation.

The “single payer” envisioned in these proposals is not today’s Medicare, of course, but an improved version of Medicare, with more comprehensive benefits, and greater ability to control costs. HR 676 may not specify an exact financing plan, but gives specific enough parameters so that whatever financing plan is adopted (one possible plan is here) it will shift the burden from the sick and poor to the healthy and wealthy, and make care free at the point of delivery. Private employers only pay a paltry 20 percent of the current health care tab, which can be recouped with a small payroll tax or tax on corporate revenues (as recently proposed by Robert Pollin for California). According to a study by David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler in the American Journal of Public Health, taxes already fund over 64 percent of health care in the United States, so moving to a publicly-funded plan is a shift, not a radical change.

Holland asserts that physicians will have to be paid less under single payer, which is false. There are many advantages to a single-payer system, not least of which is the saving of $500 billion annually currently wasted on insurance overhead and excess provider bureaucracy—more than enough money to cover the extra costs of clinical care for the uninsured and underinsured, and to eliminate copays and deductibles for everyone, without cutting physician pay. Having said that, the single payer system will have the ability to shift more funding towards primary care over time, which would help with both access and costs down the road.

Bizarrely, Holland tries to revive Jacob Hacker’s discredited proposal for a “public option” that would compete with private insurers. The premise for Hacker’s proposal is that Americans are “stubbornly attached,” in Hacker’s words, to employer-based insurance and don’t want to give it up, refuted by Kip Sullivan in this blog post. But polls show that over two-thirds of Americans favor Medicare for All. Adding one more insurance company to our fragmented and failing health system will not cover everyone or control costs.

Proposals for incremental reform to “fix” rather than “repeal” the ACA are now on the congressional agenda, but much more fundamental reform is needed. If Congress passed single payer today, we could implement it within a year and save tens of thousands of lives. Time to get to work.

Ida Hellander, MD

Ida Hellander, MD, is a former executive director and director of national health policy (1992–2017) at Physicians for a National Health Program.

Medicare for All Should Be a Litmus Test

by Adam Gaffney - The Jacobin - August 10, 2017

Fresh off a victory against Trumpcare, health care activists are now looking hopefully towards the future. Already there has been significant progress: within the Democratic Party “Medicare for All” has now achieved a level of support and enthusiasm unprecedented in recent memory.

Yet even as a broad spectrum of progressives coalesces around the cause, others are warning that we should be pressing on the brakes, not the throttle. Joshua Holland penned a piece in the Nation making this case just last week, and Paul Krugman made many similar points in his New York Times column on Monday.

Both argue that single payer should not be a “litmus test” for progressive candidates. They’re sorely mistaken.

Let’s begin with Holland’s arguments as to why Medicare for All may not be the best solution to our health care woes. Holland opens by asserting that while advocates want to use Medicare as the model for single payer universal health care, “Medicare isn’t a single-payer system in the sense that people usually think of it.” After all, he correctly notes, Medicare is partially privatized (via Medicare Advantage plans run by private insurers, as well as in the privatized design of its drug benefit). In addition, because Medicare imposes out-of-pocket expenses on enrollees (for example, co-payments and deductibles) and fails to cover some services, many enrollees purchase supplementary coverage (“Medigap” plans).

“The array of options,” Holland writes, “can be bewildering — it’s a far cry from the simplicity that single-payer systems promise.”

Indeed it is! Which is precisely why prominent single-payer proposals discard these flawed elements. Medicare Advantage primarily functions as a siphon from the public purse to insurance company coffers, and Medicare’s out-of-pocket payments squeeze many seniors. Both are unnecessary. Both should be nixed.

There seems to be some confusion here between what we might call “Currently Existing Medicare for All,” which basically nobody is proposing, and what advocates mean when they speak of “Medicare for All.” But there shouldn’t be: you don’t have to read Conyers’s bill to know that its title is not the “Medicare-for-All Act,” but rather the “Expanded and Improved Medicare-for-All Act.” Holland clearly understands this (he mentions later in his piece that Conyers’s legislation lacks cost-sharing and includes comprehensive benefits), but for the most part he fails to incorporate it into his analysis, leading him to erroneous conclusions.

Consider, for instance, a second point that Holland and Krugman raise: the disruptive impact that single payer could have for those who are already insured through their employer. Krugman believes that problems might arise when the “156 million people who currently get insurance through their employers, and are largely satisfied with their coverage,” switch to single payer. Holland is even more fretful about the political impact of such “loss aversion,” arguing that the portion of the population that enjoys decent employer-sponsored plans may not be thrilled at the idea of being shepherded into Medicare.

“Many employer-provided policies cover more than Medicare does,” he notes, “so a lot of people would objectively lose out in the deal.”

But would they? Again: all major single-payer proposals go beyond Medicare, eliminating cost-sharing and covering a more comprehensive array of health care benefits.

What differentiates the small-bore approaches that Holland and Krugman support from the deeper reform that single-payer advocates propose is that the latter is designed to improve health care for everybody, not just to make sure the uninsured get some form of coverage. After all, despite the talk about people wanting to keep their good employer-sponsored plans, in 2016 29 percent of covered workers had a high-deductible health plan (up from 4 percent in 2006), while the dollar value of workers’ deductibles has shot up by 300 percent since 2006.

Workers also often face copayments and coinsurance (a percent of the cost of the health care service paid out of pocket) for doctors’ visits, hospitalizations, tests, and drugs. And such payments are generally much higher under the non-group private plans purchased on or off the Obamacare exchanges. Many also have to deal with shifting — and often narrow — networks of doctors and hospitals, to the great detriment of doctor-patient relationships and continuity of care, not to mention choice and equal access.

In short, Holland’s point about “loss aversion” misses the mark by a mile: who would resent exchanging a limited network, high-deductible private insurance plan for a public plan that provided first-dollar comprehensive coverage without networks, and which could never be taken away?

Holland doubles down on this point, however, and brings up a related concern. He suggests that because some doctors might not take part in the national health program, “we couldn’t even promise that if you like your physician you can keep seeing him or her.” Yet a single-payer system would be the only game in town: while a tiny percentage of physicians might cater to the rich with boutique concierge practices, we can safely predict that the vast majority of physicians would participate in the national health program.

Why? Well, consider that even today (when there are alternative forms of insurance), some 93 percent of primary care doctors who see adults accept Medicare — essentially the same percent as those who accept private insurance. This rate would presumably be even higher under Medicare for All. Canadian physicians, after all, do quite well under the country’s single-payer system. And to ensure the same held true in the US, we could subsidize the educational costs of health care workers who participate in the national health program, as the latest proposal from Physicians for a National Health Program recommends.

Holland is on firmer ground when he moves to the issue of overall health care spending. While single payer would produce administrative savings, he’s right to note that we can’t reverse history: implementing Medicare for All wouldn’t suddenly bring US health care expenditures in line with those of single-payer countries. But so what? It doesn’t need to.

International examples strongly indicate that, at the very least, single payer should be no more expensive (in terms of overall national health spending) than what we have today. And what single-payer advocates are really arguing is not that we will soon be spending the same percentage of GDP on health care as Canada, but rather that by eliminating the enormous waste of the extractive and useless private health insurance apparatus and slashing drug prices (among other efficiencies), we will generate the savings we need to create the system we want: one in which everybody has first dollar coverage and equitable health care access.

But might there be a third, less disruptive, alternative to the status quo and single payer?

On the one hand, many other systems don’t actually do the sorts of things that single-payer advocates are calling for in the US (this is Holland’s point); on the other, single payer is not the only international example worth considering (a point that both Holland and Krugman stress).

Holland, for instance, notes that US single-payer proposals go beyond Canadian Medicare, which doesn’t cover prescription drugs or dental and eye care, causing many to buy supplementary insurance plans. This is true, yet it only reinforces the argument for a better single-payer system here. Canadian Medicare should cover those things; the fact that it doesn’t is one flaw of that overall superior system. One study, for instance, found that among eleven high-income nations, Canada was surpassed only by the US in the proportion of residents aged fifty-five and over who didn’t take medications because of cost. Not surprisingly, progressives in Canada are pushing for universal drug coverage.

Pointing out other single-payer systems’ shortcomings, then, is hardly a knock against a proposal for a more comprehensive single-payer system here.

In other respects, however, it’s not clear that single-payer advocates are asking for much more. Holland asserts, for instance, that “no other health care system offers such expansive benefits” as Conyers’s Medicare-for-All bill, which eliminates out-of-pocket costs for all health care services. While it is true that most systems have some form of (rather limited) cost-sharing, this is both unnecessary, and not universally the case, as Holland seems to suggest. There are no co-payments (much less deductibles) for doctor visits or hospitalizations in Canada or the United Kingdom. And in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, prescription drugs are free for all.

The second and larger point that Krugman and Holland stress is that some European nations have more of a mixed private-public model, and thus that single payer is not the only option. “There are lots of ways to skin this cat,” Holland writes. But while it is true that every health system is something of a snowflake, the best European examples share some key similarities. What we call single payer is basically national health insurance, which despite some (mostly unnecessary) organizational heterogeneity and complexities is what basically exists in countries like Australia, Canada, and (for the most part) France. The United Kingdom also has a single-payer system, albeit coupled with a more socialized delivery system: nationalized hospitals.

Other nations admittedly have more complex systems. Making sense of the basic nature of Germany’s system, for instance, has been called something of a “puzzle,” yet its not-for-profit system of highly regulated statutory sickness funds — jointly run by labor and employers — barely resembles the Obamacare system, and might better be seen as a decentralized form of national health insurance.

Then there is the Dutch example, often cited by those who find the incremental road appealing. However, though it is true that in 2006 the Dutch transitioned toward a somewhat more market-oriented, Switzerland-like, “managed competition” model, its system remains tightly regulated well beyond the Obamacare system; more importantly, evidence suggests that the managed competition makeover wasn’t particularly helpful, and indeed may have had a dubious impact in terms of equity and efficiency. As Kieke Okma, Theodore Marmor, and Jonathan Oberlander concluded in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011:

The Dutch experience provides a cautionary tale about the place of private insurance competition . . . The idea that the Dutch reforms provide a successful model for US Medicare to emulate is bizarre. The Dutch case in fact underscores the pitfalls of the casual use (and misuse) of international experience in US health care reform debates.

Two final, key points: first, it is not clear that transitioning to a more complicated public-private model that turns insurers into nonprofit, highly regulated funds will be more politically feasible in the US than going all the way to national health insurance. The industry will fight both to the death. And second, hybrid models — like those in the Netherlands and Switzerland — are less efficient than fully public ones. If first-dollar comprehensive universal health care under single-payer produces some new costs (and it will), achieving such a system would only be that much more expensive, and perhaps truly unaffordable, when implemented within the framework — and subordinated to the interests of — the bloated private insurance industry.

In reality, neither Holland nor Krugman are recommending we adopt the Dutch model. What is it, then, that the Medicare-for-All naysayers are actually promoting in place of single payer?

Krugman mentions that the public option should be strongly considered, but that otherwise progressives should basically abandon health care reform and move on to other things. Holland, for his part, more explicitly discusses an ambitious public-option-like program drawn from political scientist Jacob Hacker, which he calls “Medicare-for-All-Who-Need-It.” But here’s the thing about both: they would not, if achieved, deliver the benefits that Medicare-for-All proponents are fighting for.

This is not simply about different ways to skin a given cat, as Holland writes, but about which particular cat we intend to skin (with due apologies to cat lovers). Single-payer advocates’ aims are admittedly ambitious, yet also quite clear: we want to eliminate uninsurance and underinsurance, and create a right to equitable, comprehensive, first-dollar health care for everyone in the country, as soon as possible. And our proposals (e.g., the Conyers bill) would achieve those goals if implemented.

The more incremental reform proposals wouldn’t. As I’ve written recently, adding a public option to the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces would — according to the Congressional Budget Office — fail to even reduce the number of uninsured. And the admittedly far more robust Medicare for Some that Holland seems to favor would — even if it nearly eliminated uninsurance (hardly a certainty) — fail to remedy the US health care system’s other fundamental flaws.

What would it do for the growing ranks of the underinsured, including workers with employer plans who are being squeezed by rising deductibles and soaring drug costs? What would it do for those insured under Medicare, who lack access to important services like dental care, or who face cost-sharing that takes a sledgehammer to their finances? What would it do for drug prices on the national level? And how would it create the system-wide savings needed to achieve the comprehensive, first-dollar system single-payer proponents are struggling for?

Critiques like Holland and Krugman’s therefore crumble at the most basic level. With Improved and Expanded Medicare for All, we are aiming to improve health care for all — which is precisely what makes our project so politically potent, and hence possible: it is a universal program that, by giving something to nearly everybody, is designed to bring together the admittedly enormous coalition required to win it.

Those with Medicaid would retain their (often) broad benefits, but would enjoy equity of access. They’d be able to go to the same doctors and hospitals as everybody else, and perhaps more importantly, not worry about losing coverage as soon as they receive a tiny raise. Those insured by their employers (or via the Obamacare exchanges) would see their deductibles melt away, their networks expand, and the fear of losing coverage disappear forever. Those with Medicare could stop using scant household funds to buy supplementary “Medigap” plans, and would have their teeth cared for. And none of us would need to worry about getting dropped from our health coverage — or facing a medical bill, much less a medical bankruptcy — until the end of our days.

Sound good? It would be. Seem bold? Absolutely, but other nations show that it’s possible. Should Medicare for All be a litmus test? Damn right.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/08/medicare-for-all-health-care-obamacare-single-payer

The Nation Reader Comments

Don McCanne says:

August 17, 2017, submitted at 11:13 am

Since Joshua Holland has had both the first and last word, this addendum is appropriate.

Holland mentions loss aversion and status quo bias and offers the example of some seniors giving up their Medicare Advantage plans, but that would not be all that bad. The proposed Medicare-for-All benefits would be greater, and patients would have free choice of their physicians and hospitals instead of being limited to the provider networks of the insurer. Also, Medicare Advantage plans have been wasting taxpayer dollars through favorable selection (marketing to the lower-cost healthier beneficiaries) and by gaming risk adjustment, not to mention diverting taxpayer funds to passive investors.

Holland seems to dismiss the evidence of a surge in support for single payer by citing the Pew poll reporting that only 33 percent supported “a single national government program.” If he had checked the topline of the Pew poll he would find that only 60 percent were asked this question. The 33 percent was the portion of the total population polled, including those not asked the question, but it was 55 percent of those who were asked - a number closer to other polls on single payer. (Yes, they had filtered out the remaining based on a question about government responsibility for making sure all Americans had coverage, but that is not dissimilar to earlier poll results showing that Americans support the Affordable Care Act but oppose Obamacare. It is a glitch that limits the interpretation of the results.)

But the fundamental problem presented by Holland, Baker, Pollack, Hacker and others is that they support a universal, public health care financing program, regardless of the single payer label, yet they insist on taking at least two steps over the chasm. There is no dispute about policy. Single payer is much more effective, efficient, equitable and affordable than other comprehensive models, except for a national health service. The debate seems to be over negotiating the political barriers to reform.

In supporting various incremental reforms, they would leave in place the most expensive and least efficient model of financing health care - our current fragmented, dysfunctional multi-payer system composed of a multitude of private and public programs.

Once you get down to designing a public option or modifying Medicare for individual purchase, you end up with only one or two more options in our dysfunctional market of private plans. You gain almost none of the efficiencies of a single payer system, and you can be sure that the insurers will be there to see that the design will prevent “unfair competition” by the public insurer (ironic considering that their gaming has given their private Medicare Advantage plans an unfair financial advantage over the traditional Medicare program, at taxpayer expense).

Holland, Pelosi and many others suggest that we enact single payer on a state level first, but that would require comprehensive federal legislation to free up funds to be used by states - simple waivers will not do it since they are very limited by law in what they can accomplish. Also there is risk that conservative state administrations would not provide a program that would adequately serve their residents (think of the refusal to accept federal funds for Medicaid).

The single payer policies are the moral imperative - affordable health care for absolutely everyone. Incremental measures leave the current botched up policies in place. Instead of trying to compromise on policy, we need to fix the politics. Hopefully Holland and the rest will work with us on that.

Don McCanne, MD is senior health policy fellow for Physicians for a National Health Program.

An astonishing change in how Americans think about government-run health care

by Sarah Cliff - VOX - August 16, 2017

For the past few years, pollsters have asked about a thousand or so Americans the same question: Does the government have an obligation to ensure all Americans have health care?

They've found a remarkable shift, with Americans swinging sharply toward the belief that the government ought to play a very large role in the health care system.

Specifically, the percentage of Americans who think the government has an obligation to ensure coverage to all citizens has risen from 42 percent in 2013 to 60 percent in 2017.

New England Journal of Medicine

New England Journal of Medicine

An 18-point swing in just four years is a remarkably fast change in the world of public policy polling.

"When we reviewed everything, nothing else in our data was close to 18 points," says Harvard's Robert Blendon, who published the data in today's New England Medical Journal.

To put that in context: Although much fanfare has been made out of improving views of the health care law, when Blendon averaged together national polling, he found the law's favorability ratings had only risen 5 percentage points.

Blendon attributes the change in attitudes to Americans thinking through the consequences of repealing the Affordable Care Act, resulting in millions losing coverage. The question didn't ask about Obamacare specifically, a highly polarizing law. Instead, it asked generally about the government's role in providing coverage.

"People have not fallen in love with the ACA," Blendon says. "What they fell in love with was the idea that the federal government can't drop 30 million people from coverage all at once, that there was a responsibility for universal coverage."

His article also finds that government health programs, like Medicaid, generally poll better than the expansion of private coverage through insurance subsidies.

Most Republican voters say they do not want to cut the number of people covered through Medicaid, the public program that provides health insurance to low-income Americans. But most Republicans were open to cutting subsidies for private insurance.

"Medicaid emerged out of this debate with an awful lot of sympathy," Blendon says. "The majority of every group we looked at did not want to see the number of people covered by the program cut."

For me, Blendon's findings (and the chart above, in particular) do a lot to explain why Republicans have so far failed to deliver on their promises to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

It's not just the fact that millions of Americans now rely on the law and its programs for coverage. And it's not the rise in Obamacare's popularity, which has been relatively meager.

It's also a fundamental shift in attitudes that has happened after the Affordable Care Act passed, where Americans became more accepting of a larger role for the government in health care. For all the attacks on the health law as a "government takeover" of health care, this polling suggests voters are kind of okay with that.

Health Care in New York

by Richard Gottfried - NYT - August 16, 2017

To the Editor:

Re “How to Repair the Health Law (It’s Tricky but Not Impossible)” (front page, July 30):

The basic flaw in the Affordable Care Act is that it leaves us in the hands of insurance companies. That means rising premiums and deductibles, restricted provider networks and high out-of-network charges; huge multiple administrative bureaucracies and profits; and the costs that doctors and hospitals incur for dealing with them.

We should start with a basic principle: No American should be denied health care or suffer financially trying to pay for it. What makes that “tricky” — and forces health policy into contortions — is insisting on taking care of insurance companies and their hefty costs and finances.

The one way to provide all of us with health care and financial security that is most practical and least expensive is to take insurance companies out of the picture and enact improved Medicare for all.

Washington seems a long way from doing that. But progressive states like New York can create state universal public health coverage.

RICHARD N. GOTTFRIED, NEW YORK

The writer is chairman of the New York State Assembly Health Committee and the sponsor of the New York Health Act (A. 4738) to establish a single-payer system in New York.

It shouldn't take generous

strangers to help patients cope with drug prices

by David Lazarus - LA Times - August 18, 2017

The inherent goodness of people was made clear this week when a pair of readers offered to pay for a 75-year-old Encino man’s prescription meds after the drug maker imposed a $1,100 deductible to be eligible for financial assistance.

Meanwhile, the warped priorities of our for-profit healthcare industry once again tumbled into the open as the drug company in question, Eli Lilly & Co., responded to this demonstration of humanitarian fellowship with a shrug of its corporate shoulders.

Call me a starry-eyed optimist, but I had a notion that Lilly, shamed by this act of generosity, would have bent its own arbitrary rules and waived the deductible for a cash-strapped senior.

Instead, the company dug in its heels and refused to even take the money, insisting that it be spent instead at a drugstore before Lilly’s financial assistance would resume.

I wrote on Tuesday about Ed Wright, who for 14 years has received the growth hormone Humatrope from Lilly free of charge under the company’s Lilly Cares program. Most drug makers offer such assistance for eligible patients, typically people on fixed incomes who have chronic medical conditions.

This year, Lilly imposed a requirement that most program participants spend $1,100 on prescription drugs before being eligible for the company’s largesse. Steven Stapleton, president of the Lilly Cares Foundation, explained to me in a statement that the company wanted to “balance all the criteria for the program.”

Whatever that means.

What it meant for Wright, though, was that he’d no longer be able to afford his medication, which even with Medicare can cost about $700 a month. He told me he’d started rationing his doses and expected to run out within a few weeks.

Shortly after the column appeared, Ventura resident Karen O’Neil, 71, contacted me to say she’d be willing to pay the $1,100 on Wright’s behalf.

“I could very easily be in the same boat,” she said, adding that she felt moved to do something after reading about Wright “taking half-doses because he can’t get his medication.”

I was contacted as well by Richard Geringer, 66, an Aliso Viejo lawyer who also was willing to pony up the $1,100. He said he was motivated by the fact that he too relies on a costly medication for his own condition, ulcerative colitis, which he described as “like having a million little volcanoes” in his intestines.

“I’m fortunate that Medicare covers my treatment,” Geringer told me. “When I read about Mr. Wright, I thought, ‘This isn’t good.’”

After I informed Wright about the offers of financial assistance, he called Lilly Cares to ask if he could arrange for the money to be sent to the drug maker so he could resume his Humatrope doses.

Wright told me they turned him down flat, insisting that he had to go out and spend $1,100 at drugstores before Lilly Cares would care again.

Stapleton, the Lilly Cares Foundation president, said in a second statement that the program “cannot be involved in connecting a patient with a donor,” which seems beside the point considering that it’s me, not the foundation, doing the connecting.

He also said that Medicare beneficiaries such as Wright are required to spend $1,100 “on any prescription drug made by any manufacturer to be eligible for free Lilly medicine for the rest of the year.”

I asked a Lilly Cares service rep why the company is so determined to have people spend money on any drug from any manufacturer. What’s the benefit to Lilly, except to maintain the drug-market status quo? The rep said she had no answer to that question.

Jason Doctor, an associate professor at USC’s School of Pharmacy, said it appeared that Lilly had made it pointlessly difficult for a person in need to receive the company’s aid.

“It seems fair to say that their patient-assistance program is not working well for people who can’t afford drugs,” he said.

The obvious workaround here is for O’Neil and Geringer to give Wright enough to purchase a couple of doses of Humatrope, thus qualifying him once again for Lilly’s assistance. I’m now setting that up.

But it’s all so unnecessary. The only thing that has been accomplished is that Lilly has goosed its sales a little higher while still enjoying the pretense of being a good corporate citizen. (The company receives a healthy tax write-off for its Lilly Cares program.)

Actually, what’s also been accomplished, thanks to O’Neil and Geringer, is recognition that there are decent people out there ready to help someone in need, no strings attached.

Drug companies point to their patient-assistance programs as evidence that their hearts are in the right place.

The Lilly Cares website says that “it's important to us to make sure that those who can benefit from these medicines have access to them.”

I don’t want to imply that Lilly isn’t doing good by making millions of dollars worth of meds available to people who couldn’t otherwise afford them.

But there’s another road they and other drug companies could take: charging reasonable prices to begin with.

O’Neil put it best: “It’s great that we can help one person. But there are thousands and thousands of others out there.”

And not enough Good Samaritans to go around.

Bills for $25 or less mistakenly sent to collection agency by MaineGeneral

by Betty Adams - Kennebec Journal - August 11, 2017

AUGUSTA — MaineGeneral Medical Center apologized Friday to about 9,700 patients who received letters from a collection agency before they had even gotten statements from the hospital on their balances – all of which were $25 or less.

“A technical error occurred leading to a file transfer of bills of $25 and less going to The Thomas Agency,” MaineGeneral spokeswoman Joy McKenna said in an email Thursday. “The bills are for services provided at MaineGeneral within the past year.”

Patients who owe $25 or less received letters from The Thomas Agency, a debt collector with offices in Portland and Brewer, in the past week.

The letters, dated July 31, say that the bills can be paid by credit card or by mail to a Portland post office box, and include a notice that unless The Thomas Agency is notified within 30 days, it will assume the debt is valid.

On Friday, MaineGeneral Health Chief Financial Officer Terry Brann issued an apology on behalf of the health care system.

“We have isolated the cause for the error and are implementing corrections to ensure this does not happen again in the future,” he said in an email. “Patients’ credit ratings are not impacted by this occurrence. We apologize for the confusion caused by these letters.”

Will Lund, superintendent of the Maine Bureau of Consumer Credit Protection, said that while his office has not received consumer complaints about the recent letters, “Most medical providers try to make sure a bill gets to a patient before it gets to a debt collection agency.”

He also noted that medical bills are payable when services are provided, as most health care facilities indicate in their offices. He also said he did not anticipate that information about the debts would be forwarded immediately to credit reporting companies. Lund attributed that to three factors in what he termed “the nature of medical debt.”

“There’s the uncertainty caused by the insurance process,” he said. “Hospitals are notorious about having old addresses on file; collectors are much better about finding where we are now. Many of us are responsible for bills that aren’t even our own. Parents generally agree to pay the bills of minors. If the parents are divorced or separated, the bills could come as a surprise to one parent or the other.”

MaineGeneral Medical Center operates under MaineGeneral Health, which recently ended its last fiscal year in the red.

To help shore up the system’s finances, administrators eliminated about $5.4 million in recurring expenses for supplies, contracts and other costs. And for the last two pay periods of the fiscal year in June, they cut the earned time off that employees see on their paychecks.

People with concerns about receiving a collection letter can call the numbers on the letter – 772-4659 or (800) 639-2408 – which go to The Thomas Agency, or they can call MaineGeneral’s customer support at 872-4680 or toll-free at (877) 255-4680.

Health Insurers Get More Time to Calculate Increases for 2018

by Robert Pear - NYT - August 13, 2017

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration is giving health insurance companies more time to calculate price increases for 2018 because of uncertainty caused by the president’s threat to cut off crucial subsidies paid to insurers on behalf of millions of low-income people.

Federal health officials said the deadline for insurers to file their rate requests would be extended by nearly three weeks, to Sept. 5.

The extension was announced in a memorandum that insurers received on Friday from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which runs the federal insurance marketplace and regulates insurers under the Affordable Care Act.

It was the clearest evidence to date that the politics of health care in Washington could disrupt planning for 2018. Insurers are struggling to decide whether to participate in the marketplace next year and, if so, how much to charge.

In addition to the usual price increases to keep up with medical inflation, many insurers are demanding higher rates because of the possibility that President Trump might take away the subsidies known as cost-sharing reduction payments. The subsidies compensate insurers for reducing deductibles, co-payments and other out-of-pocket medical costs for low-income people.

Mr. Trump has repeatedly threatened to cut off the payments as a way to force Democrats to negotiate over the future of the Affordable Care Act.

The president can stop the payments because a federal judge ruled last year that the Obama administration had been illegally making the payments in the absence of a law explicitly providing money for the purpose. The Obama administration appealed the ruling, and the payments continue from month to month, with permission from the court. But Mr. Trump could drop the appeal and stop the payments at any time.

In its latest bulletin, the Trump administration said that many state insurance commissioners had allowed insurers to increase rates for 2018 to account for the “uncompensated liability” that they might face for the cost-sharing reductions.

The amount of the increases varies, but many insurers say that prices will be 15 to 20 percent higher next year because they do not know if they will receive the subsidies they are anticipating.

The future of the subsidies has been uncertain since Republican efforts to repeal major provisions of the Affordable Care Act collapsed last month in the Senate, where three Republicans joined all Democrats in voting down a proposal drafted by the majority leader, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky. Mr. Trump chided Mr. McConnell for the failure and urged him to keep trying.

The impasse is already taking a toll.

“Planning and pricing for A.C.A.-compliant health plans has become increasingly difficult due to a shrinking and deteriorating individual market, as well as continual changes and uncertainty in federal operations, rules and guidance, including cost-sharing reduction subsidies,” one of the nation’s largest insurers, Anthem, said last week in explaining its decision to curtail its participation in the individual market in Nevada and Virginia.

Congress could reduce the uncertainty and stabilize insurance markets by providing money for the cost-sharing subsidies — a step supported by doctors, hospitals, insurers, consumer groups, the United States Chamber of Commerce and the influential chairmen of three congressional committees: Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee and Representatives Kevin Brady of Texas and Greg Walden of Oregon, all Republicans.

Some lawmakers, however, want to offset the cost of the subsidies, estimated at $7 billion to $10 billion next year, perhaps by cutting other health programs. Moreover, many Republicans criticize the subsidies as a bailout for insurers and say they will not provide the funds unless Congress also takes steps to reduce insurance costs and cut back federal regulation of the industry.

Lawmakers plan to return from their summer recess on Sept. 5, so they will not provide any definitive guidance before insurers file their rates on the same day.

How Donald Trump Is Driving Up Health Insurance Premiums

by Steve Rattner - NYT - August 15, 2017

Health insurance premiums for 2018 are on the rise for many, and for that, most of the blame falls squarely on the shoulders of President Trump.

In recent days, a bevy of insurers have announced significant increases for Americans who purchase their coverage on the exchanges: a minimum of 12.5 percent by Covered California, 34 percent by Anthem in Kentucky and 43.5 percent by Medica in Iowa, to name just a few.

Still more hikes may come from these insurers and others, who cite uncertainty around the Affordable Care Act as the principal culprit in this disturbing trend.

Reinforcing these developments is an analysis by Charles Gaba of acasignups.net, who projected that at the moment, average premium increases next year are likely to total around 29 percent.

Of that, just 8 percentage points will result from medical inflation, and 2 percentage points will stem from the reinstatement of an Obamacare health insurance tax; the balance will be related to the uncertainty that Mr. Trump has created around key pieces of Obamacare.

The largest portion of the total — about 15 percentage points — is connected to the potential demise of the cost-sharing reductions (known as C.S.R.s), payments made by the government to insurers to help cover out-of-pocket costs like co-pays and deductibles that lower-income Americans can’t afford.

(The Congressional Budget Office said on Tuesday that premiums for the most popular health insurance plans would rise by 20 percent next year, and federal budget deficits would increase by $194 billion in the coming decade, if Mr. Trump ends the subsidies.)

Those subsidies, which were created by the Obama health care legislation and which benefit seven million Americans, have been in limbo since House Republicans sued in 2014, contending that they needed to be appropriated by Congress, which wasn’t going to happen as long as Republicans controlled each chamber.

Conservatives won the first round in court, but that decision was stayed pending appeal, allowing both the Obama and Trump administrations to continue to make the monthly payments.

President Trump has threatened to end the subsidies but has yet to take definitive action. A decision was promised by Aug. 4, but Mr. Trump decamped to his New Jersey golf resort with nary a word about C.S.R.s.

As a result, many of the insurance companies that have already announced their increases have either baked in increases assuming loss of the subsidies or say that they will impose further hikes if the subsidies are not continued.

The silence around the C.S.R.s is consistent with the new administration’s overall approach to the A.C.A.: continually badmouthing it and taking small steps to undermine it without unleashing a full-force assault.

Even without “repeal and replace” legislation emerging from Congress — an unlikely event at this point — the administration has enormous authority to shape the functioning of the A.C.A.

As Tom Price, the secretary of health and human services, has said repeatedly, there are 1,442 places in the existing law that provide him with some measure of discretion in how the act is implemented.

For example, the Internal Revenue Service said this year that it would start accepting tax returns even if the filer has not confirmed having insurance or submitting the penalty.

Around the same time, the new team pulled advertising designed to encourage enrollments, causing sign-ups for 2017 to fall modestly short of expectations, especially among younger and healthier Americans, who are much more likely to wait until the last minute to enroll.

More recently, the administration canceled contracts with two companies that helped Americans in 18 cities find plans.

All of these actions — and more — could amount to undermining the individual mandate, a step that Mr. Gaba says would add another 4 percentage points to 2018 premium increases.

At the same time, some steps toward preparing for the next enrollment period are proceeding normally, such as an annual meeting in June with “navigators” who guide consumers in their choices of plans.

In addition, the Trump team has been allocating funds to states with weak exchange markets to encourage insurers to continue to provide coverage.

But what else the administration will or won’t do as the November opening of the enrollment period approaches remains a mystery.

Asked last week by The Washington Post to clarify, a spokeswoman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would say only, “As open enrollment approaches, we are evaluating how to best serve the American people who access coverage on HealthCare.gov.”

An hour later, the spokeswoman, Jane Norris, tried to withdraw the statement and refused to comment further. Ms. Norris’s office did not respond at all to my inquiry.

A bipartisan group of senators is trying to draft legislation to stabilize Obamacare. But with Congress gone, any new laws will come too late for the Sept. 5 deadline for setting 2018 premiums.

So it well may be up to Mr. Trump to decide, in effect, the fate of the exchanges, which supply about 12 million Americans with their coverage. With final premium increase decisions due soon, even inaction could be devastating.

As the president has acknowledged on occasion and as public opinion polls confirm, the failure of Congress to pass any legislation means that the new administration “owns” the health care issue politically. Continuing to let it flounder in the twilight zone will be damaging not only to Mr. Trump’s political health but more important, to the health of millions of Americans who deserve better.

Trump Threat to Obamacare Would Send Premiums and Deficits Higher

by Robert Pear and Thomas Kaplan - NYT - August 15, 2017

WASHINGTON — Premiums for the most popular health insurance plans would shoot up 20 percent next year, and federal budget deficits would increase by $194 billion in the coming decade, if President Trump carried out his threat to end certain subsidies paid to insurance companies under the Affordable Care Act, the Congressional Budget Office said Tuesday.

The subsidies reimburse insurers for reducing deductibles, co-payments and other out-of-pocket costs that low-income people pay when they visit doctors, fill prescriptions or receive care in hospitals.

Even before efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act collapsed in the Senate last month, Mr. Trump began threatening to stop paying the subsidies, known as cost-sharing reductions. He said the health care law would “implode” and Democrats would have no choice but to negotiate a replacement plan. Mr. Trump described his strategy as, “Let Obamacare implode, then deal.”

Those threats continue, though the Trump administration has paid the subsidies each month.

The nonpartisan budget office has now quantified the cost of the threats and potentially handed Democrats a weapon to force Congress and the administration to keep the money flowing.

“Try to wriggle out of his responsibilities as he might, the C.B.O. report makes clear that if President Trump refuses to make these payments, he will be responsible for American families paying more for less care,” the Senate Democratic leader, Chuck Schumer of New York, said. “He’s the president and the ball is in his court — American families await his action.”

If Mr. Trump stops payment of the subsidies, the budget office said, insurers will increase premiums for midlevel “silver plans,” and the government will incur additional costs because, under the Affordable Care Act, it also provides financial assistance to low-income people to help them pay those premiums.

Insurers in some states would withdraw from the market because of “substantial uncertainty” about the effects of the cutoff, the budget office said. About 5 percent of the nation’s population would have no insurers in the individual insurance market next year without the subsidies, it said. By contrast, if the subsidies are paid, fewer than one-half of 1 percent of people would be in such areas, the report said.

The federal government helps pay premiums for low-income people by providing them with tax credits, which generally insulate them from insurance price increases.

“Gross premiums for silver plans offered through the marketplaces would be 20 percent higher in 2018 and 25 percent higher by 2020 — boosting the amount of premium tax credits according to the statutory formula” in the Affordable Care Act, the budget office said.

The budget office does not foresee much change in the number of people who are uninsured if the cost-sharing subsidies are halted. “The number of people uninsured would be slightly higher in 2018 but slightly lower starting in 2020,” it said.

A White House spokesman, Ninio Fetalvo, said Tuesday that “no final decisions” had been made regarding the subsidy payments.

“Regardless of what this flawed report says, Obamacare will continue to fail with or without a federal bailout,” Mr. Fetalvo said. “Premiums are accelerating, enrollment is declining, and millions are seeing their options dwindling. This disastrous law has devastated the middle class and must be repealed and replaced.”

The dispute over the subsidy payments dates to 2014, when House Republicans filed a lawsuit asserting that the Obama administration was paying the subsidies illegally because Congress had never appropriated money for them. Last year, a federal judge agreed. The judge ordered a halt to the payments but suspended the order to allow the government to appeal. The case is pending before the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

The Trump administration has been providing funds for cost-sharing subsidies month-to-month, with no commitment to pay for the remainder of this year, much less for 2018.

The budget office study was requested by the House Democratic leader, Nancy Pelosi of California, and the House Democratic whip, Steny H. Hoyer of Maryland. “If he follows through with his threats,’’ Ms. Pelosi said on Tuesday, “President Trump will be single-handedly responsible for raising premiums across America by 25 percent, exploding the deficit by nearly $200 billion, and creating more bare counties” without insurers.

Mr. Trump and some Republicans in Congress call the payments a bailout for insurance companies. But under the Affordable Care Act, insurers are required to provide the discounts to low-income people, who they say are the real beneficiaries.

Ending the cost-sharing subsidies would confound the expectations on which the current marketplace is based. People with incomes from 200 percent to 400 percent of the poverty level (roughly $23,750 to $47,500 a year for an individual) could get larger tax credits and could use them to buy more robust plans covering a larger share of their medical expenses, the budget office said.

Thus, for example, a 40-year-old with income of $34,000 would pay about $3,350 a year — after tax credits — for a “silver plan” in 2026, but could get a more generous gold plan for several hundred dollars less, the budget office said. In other words, for some consumers, gold plans could be cheaper than silver plans.

“As a result,” the budget office said, “more people would purchase plans in the marketplaces than would have otherwise, and fewer people would purchase employment-based health insurance — reducing the number of uninsured people, on net, in most years.”

About six million people are receiving the cost-sharing subsidies, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. Terminating those subsidies would save the government $8 billion next year and a total of $118 billion through 2026, the budget office said. But those savings would be swamped by the increased cost of premium tax credits, it said.

Doctors, hospitals, insurers, consumer groups and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce have all urged Mr. Trump to continue paying the cost-sharing subsidies. Senator Lamar Alexander, Republican of Tennessee and the chairman of the Senate health committee, has said he plans to hold hearings next month, with a view toward producing bipartisan legislation that would stabilize insurance markets and provide money for the subsidies.

“Without these payments, Americans may not have access to or be able to afford health insurance next year because of dramatic individual insurance premium increases in the individual market,” Mr. Alexander said on Tuesday.

“When the house is on fire, you put out the fire, and Congress should work quickly in September to pass limited, bipartisan legislation that funds cost-sharing payments for 2018 and gives states more flexibility to offer lower-cost plans,” he said.

Doctor Shortage Under Obamacare? It Didn’t Happen

by Austin Frakt - NYT - August 14, 2017