"Side Effects" will be performed as an integral part of the upcoming conference on "Challenges to Professionalism in a Time of Change", to be held on June 17 in Portsmouth, N.H. The conference is being sponsored by the associations of health care professionals in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, and is open to the public. For more details and to register for this important conference visit:

http://events.r20.constantcontact.com/register/event?oeidk=a07ee5zr4ri8f7e7d77&llr=w54s6qmab

-SPC

Health-care blues: writer-performer Michael Milligan in the solo show “Mercy Killers” at Taffety Punk Theatre Company. (Marcus Kyd)

Milligan’s health-care monologues give voice to patient and doctor

by Nelson Pressley - Washington Post - May 23, 2017

If you did not know that the American health-care system is complicated — and only a billionaire might be surprised — a first-rate primer is on display in Michael Milligan’s monologues “Mercy Killers” and “Side Effects.” Conveniently, for the next two weeks they’re on view just blocks from Congress at the Capitol Hill Arts Workshop.

In each of these detail-rich 65-minute confessions, presented by the savvy Taffety Punk Theatre Company and performed on alternate nights, Milligan plays likable working men under duress. He’s an Ohio auto mechanic named Joe in “Mercy Killers,” set in 2010, telling a police officer how everything unraveled once his wife got breast cancer and he battled mounting bills and elusive insurance companies. In “Side Effects,” which takes place now, he’s a doctor informing a lawyer friend about a nuisance suit as he battles with assembly-line hospital bureaucracies and, again, elusive insurance companies.

“Americans don’t mind the gulag,” the doctor grouses darkly, “as long as it’s privately run.”

Milligan takes care not to grandstand: no actual Republicans or Democrats were harmed (much) in the making of these plays. His auto mechanic is a Rush Limbaugh listener who believes in paying his own way, and Milligan — a Chicago-based actor with a good rough blue-collar edge in his voice — plays the man without an ounce of condescension. The fact that Joe has a liberal wife makes for some winsome romantic tension, while his junk-food habits and her health-nut streak is obviously ironic.

Anyone can relate to this rugged, earnest character, and anyone who’s faced the shocking costs and inconsistent coverage of serious care will either lean in attentively or slump in brutalized recognition.

Ditto for the doctor in “Side Effects.” He’s practically the same guy, but with a couple details changed: white collar and more educated, but still Middle America and grounded in a rigorous work ethic and fair play. The story arc repeats as this man, too, is crushed by gears that plainly favor neither patients nor doctors but corporate administrators and lawyers. Gallows humor is never far away as these narrators recount their travails; it’s the doctor who makes an equation of MRI, CT and ATM, but both men have a sarcastic bent drawn from depths of frustration and anger.

The dramatic setup feels awkward at first, with Milligan chatting directly to us as if we were the second party in the conversation. But it puts front and center two voices that are too little heard in the health care debate — patients/families and doctors — and Milligan is an engaging, canny actor with a gift for natural behavior and the tics of everyday speech. In both of these real-time spiels on a small, nearly bare stage he vividly shows the deep reluctance of his characters to complain while also building steam around the pressures that drive them to snap.

And boy, do they snap. Milligan has done his research, having toured “Mercy Killers” around the country and now premiering “Side Effects” with Taffety Punk. The data is authoritative; each incident about a treatment or billing code rings true, winding these guys ever tighter until they blow.

We all know that politics is more important than theater, right? But the talk is frequently deeper and better in the theater, where you have to sit, listen and think for an hour or two. Check it out, and reckon with these haggard men before deciding what we ought to do next.

Editor's Note: Here is a link to a great website, with tons of useful information about health care and the debate about health care reform. It's a great way to get yourself up to speed about the ins, outs and controversies about healthcare.

https://obamacarefacts.com/single-payer/

-SPC

Editor's Note: This link is to a now old You-Tube video of an interview with T.R. Reid, author of "The Healing of America". Unfortunately, it's still as relevant now as it was when it was made, but still very much worth watching.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kxNhOBemsic

-SPC

Editor's Note:

The following letter was submitted to the Maine Legislature's Insurance and Financial Services Committee by Lynn Cheney, chairperson of Maine AllCare's Downeast Chapter, following the legislative hearing May 4 on LD 1274, an act that would create a universal healthcare system for the state of Maine.

"Dear IFS Committee member,

On May 4th, your committee worked overtime, hearing testimony from scores of Maine people supporting comprehensive healthcare for all Mainers. You listened as your constituents told about lives devastated because of lack of healthcare. You also listened to how Maine could provide healthcare for all. You heard how publicly financed and privately delivered care for everyone would cost less, save lives and let every Mainer focus on getting well instead of worrying about paying for care. Like in Canada and France and New Zealand, and on and on. Then on May 9th, your committee unanimously recommended a feasibility study for universal health care in Maine. -SPC

Single Payer Success in NY as Medicare-for-All Bill Passes State Assembly

'The New York State Assembly is leading the way with the only kind of healthcare bill that will put people before profits'

by Diedre Fulton - Common Dreams - May 20, 2017

As the momentum behind Medicare-for-All continues to grow nationwide, New York's State Assembly on Tuesday was expected to pass a single-payer healthcare bill that puts the state light years ahead of the regressive GOP in Washington, D.C.

The New York Health Act would afford all state residents access to comprehensive inpatient and outpatient care, primary and preventative care, prescription drugs, behavioral health services, laboratory testing, and rehabilitative care, as well as dental, vision, and hearing coverage. There would be no premiums, deductibles, or co-pays; the plan would be funded through progressively raised taxes, including a surcharge that would be split 80/20 between employers and employees.

As Salon's Amanda Marcotte wrote earlier this month, the legislation's lead sponsor, Assemblyman Richard Gottfried, says "'almost all New Yorkers would pay less than they currently do' because they would be able to replace their current plans with this more affordable state-based plan."

Furthermore, Marcotte reported:

Gerald Friedman, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, agreed. In 2015 he wrote an analysis of the proposed bill and concluded that a single-payer system would save money across the board by reducing health care spending."One [advantage] is that a single-payer plan will allow providers to economize on the costs of handling the billing and insurance-related expenses," Friedman argued.

Previous incarnations of the bill have passed the lower chamber multiple times, only to not be picked up for consideration by the state Senate. This time could be different.

As the Village Voice explained Tuesday:

Currently the bill is only two votes shy of passing in the 63-seat state Senate. It recently picked up the support of the influential Independent Democratic Conference, buoying its number of supporters to 30.A special election on May 23 to fill an assembly seat vacated by now-councilmember Bill Perkins is all but guaranteed to go to real estate developer Brian Benjamin, who has vowed to support the bill, [Senate sponsor Gustavo] Rivera told the Voice. The only hurdles now include the conversion of just one more holdout—the most likely target is Senator Simcha Felder, a Democrat who caucuses with Republicans—plus a small pile of procedural battles. Felder, who told the Guardian in April that he had no position on the bill, did not respond to multiple phone calls and emails from the Voice.

With the fate of the bill now resting with the Senate, proponents like Citizen Action of New York board president Ivette Alfonso on Tuesday urged state senators "to prove once and for all they are with the people and against [President Donald] Trump."

"As the radical right wing in Washington try to disguise a $500 billion dollar tax cut for the super-rich and insurance giants as a healthcare bill, the New York State Assembly is leading the way with the only kind of healthcare bill that will put people before profits, and make healthcare what it should be, a human right," Alfonso said.

"We are at a critical juncture as Washington considers new laws that would further entrench the insurance business, setting back patient access to quality, affordable care," added Jill Furillo, a registered nurse and executive director of the New York State Nurses Association, which lobbied for the bill.

"But with this vote, the Assembly recognizes that New York is ready to move forward, not backwards, and put in place a system that makes patient need the priority and says no to health insurance gatekeepers," she said. "We salute the Assembly and urge the Senate to do the same."

Trump, Shouting ‘Death Spiral,’ Has Nudged Affordable Care Act Downward

By Robert Pear - NYT - May 20. 2017

WASHINGTON — When Aetna, the health insurance giant, announced this month that it was pulling out of the Affordable Care Act’s insurance exchange in Virginia in 2018, President Trump responded on Twitter: “Death spiral!”

When Humana announced plans to leave all the health law’s marketplaces next year, the president chimed in, “Obamacare continues to fail.”

Left unremarked on was a big reason for the instability: The Trump administration and Congress are rattling the markets.

The administration’s refusal to guarantee payment of subsidies to health insurance companies, the murky outlook for the Affordable Care Act in Congress and doubts about enforcement of the mandate for most people to have insurance are driving up insurance prices for 2018, insurers say in rate requests filed with state officials.

Opponents of President Barack Obama’s signature legislative achievement have made what may be a self-fulfilling prophecy: They repeatedly forecast the collapse of the health law, and then push it along.

Frustrated state officials have ideas for stabilizing the individual insurance market, but they say they cannot figure out where to make their case because they have been bounced from one agency to another in the Trump administration.

“We have trouble discerning who has decision-making authority,” said Julie Mix McPeak, the Tennessee insurance commissioner and president-elect of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, which represents state officials. “We reached out to the Department of Health and Human Services. They referred us to the Office of Management and Budget, which referred us to the Department of Justice. We reached out to the White House Office of Intergovernmental Affairs.”

The Trump administration has sent mixed signals, reflecting an internal debate about whether to stabilize insurance markets or let them deteriorate further. Mr. Trump has said he could cut off the subsidies at any time if he wanted to.

The government may clarify its plans in a legal brief to be filed on Monday with the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Or it could simply ask the court for a three-month extension, prolonging the uncertainty.

State insurance commissioners have joined insurers, hospitals and congressional Democrats in urging the administration to pay “cost-sharing” subsidies, and federal health officials initially indicated that they would do so. But Mr. Trump countermanded them, refusing to make any long-term commitment.

On Thursday, 15 Democratic state attorneys general, led by Xavier Becerra of California and Eric T. Schneiderman of New York, filed a motion to intervene in the case, demanding that the payments continue.

In some ways, the Obama administration shares responsibility with the Trump administration for the current mess, which has huge human, legal and political implications.

Unable to get an explicit appropriation from Congress, the Obama administration went ahead and paid the subsidies, in a way that a federal district judge later found to be unconstitutional. The ambivalence of the Trump administration has further spooked insurers.

The subsidies are paid to insurance companies so they can reduce deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for low-income consumers — seven million people this year.

Continued payment of the subsidies is “critical to the viability and stability” of health insurance markets, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners said in a recent letter to congressional leaders.

“As long as the court case, House v. Price, remains unresolved and federal funding is not assured, carriers will be forced to think twice about participating on the exchanges,” the letter said. “Even if they do decide to participate, state regulators have been informed that the uncertainty of this funding could add a 15 to 20 percent load to the rates.”

Senate Republicans, well aware of the political risks, are seeking short-term solutions for 2018 and 2019, even as they consider big changes in a House-passed bill to repeal and replace major provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

“In order to rescue Americans from collapsing Obamacare exchanges, Republicans are likely going to have to temporarily do some things we may not like, including looking at funding the cost-sharing payments,” said Senator Lamar Alexander, Republican of Tennessee and chairman of the Senate health committee.

At the same time, he said, “Democrats will have to do some things they may not like, including allowing people to use their subsidies to buy insurance outside the Obamacare exchanges” and giving states more power to decide what types of insurance can be sold.

Federal health officials say they want to stabilize insurance markets, and they issued a “market stabilization” rule last month. But the administration has also taken steps that destabilize the market, by creating doubts about subsidy payments to insurers and enforcement of the requirement for people to have insurance under the Affordable Care Act.

Anthem, one of the nation’s largest insurers, has sought rate increases of 24 percent to 38 percent in Connecticut, based on the assumption that the Trump administration will continue paying the subsidies through 2018. If that assumption is wrong, the company said, rate increases could be much higher.

With so much uncertainty, Anthem said, it expects to serve a smaller, sicker group of people next year.

“We are forecasting that the individual market will continue to shrink and that those individuals with greater health care needs will be the most likely to purchase and retain their coverage,” while “healthy members are more likely to drop coverage,” Anthem said in its Connecticut rate request.

But the cost-sharing payments are only part of the problem. Insurers said the Trump administration was also destabilizing insurance markets by indicating that it would loosen enforcement of the mandate for people to have coverage or pay a penalty.

In seeking rate increases that average more than 50 percent in Maryland, CareFirst, the state’s largest insurer, said, “We have assumed that the coverage mandate introduced by A.C.A. will not be enforced in 2018 and that this will have the same impact as repeal.”

“Failure to enforce the individual mandate makes it far more likely that healthier, younger individuals will drop coverage and drive up the cost for everyone else,” said Chet Burrell, the chief executive of CareFirst.

The bill passed by the House this month to repeal the Affordable Care Act would eliminate the cost-sharing subsidies in 2020. The outlook is unclear in the Senate, which is developing its own version of the legislation.

Democrats sought money for cost-sharing subsidies in the omnibus spending bill that Mr. Trump signed on May 5. But the White House refused to go along, sowing doubts about future payments.

“The Trump administration is paying the subsidies, but is trickling them out one month at a time,” as part of a “very cunning’’ strategy to undermine the health care law, said Senator Christopher S. Murphy, Democrat of Connecticut.

In an interview with The Wall Street Journal last month, Mr. Trump threatened to withhold subsidy payments from insurers as a way to induce Democrats to negotiate with him on a replacement for the Affordable Care Act.

If those payments are not made, Mr. Trump said, “Obamacare is gone, just gone.”

The Unfreeing of American Workers

by Paul Krugman - NYT - May 22, 2017

American conservatives love to talk about freedom. Milton Friedman’s famous pro-capitalist book and TV series were titled “Free to Choose.” And the hard-liners in the House pushing for a complete dismantling of Obamacare call themselves the Freedom Caucus.

Well, why not? After all, America is an open society, in which everyone is free to make his or her own choices about where to work and how to live.

Everyone, that is, except the 30 million workers now covered by noncompete agreements, who may find themselves all but unemployable if they quit their current jobs; the 52 million Americans with pre-existing conditions who will be effectively unable to buy individual health insurance, and hence stuck with their current employers, if the Freedom Caucus gets its way; and the millions of Americans burdened down by heavy student and other debt.

The reality is that Americans, especially American workers, don’t feel all that free. The Gallup World Survey asks residents of many countries whether they feel that they have “freedom to make life choices”; the U.S. doesn’t come out looking too good, especially compared with the high freedom grades of European nations with strong social safety nets.

And you can make a strong case that we’re getting less free as time goes by.

Let’s talk first about those noncompete agreements, which were recently the subject of a stunning article in The Times (the latest in a series), plus a report from the Obama administration pushing for limits to the practice.

Noncompete agreements were originally supposed to be about protecting trade secrets, and therefore helping to promote innovation and investment in job training. Suppose that a company trying to build a better mousetrap hires a new mousetrap engineer. Her employment contract might very well include a clause preventing her from leaving a few months later for a job with a rival pest-control firm, since she could be taking crucial in-house information with her. And that’s perfectly reasonable.

At this point, however, almost one in five American employees is subject to some kind of noncompete clause. There can’t be that many workers in possession of valuable trade secrets, especially when many of these workers are in relatively low-paying jobs. For example, one prominent case involved Jimmy John’s, a sandwich chain, basically trying to ban its former franchisees from working for other sandwich makers.

Furthermore, the terms of the clauses are often defined ridiculously widely. It’s as if our hypothetical mousetrap engineer were prohibited from seeking employment with any other manufacturing firm, or in any occupation that makes use of her engineering skills.

At this point, in other words, noncompete clauses are in many cases less about protecting trade secrets than they are about tying workers to their current employers, unable to bargain for better wages or quit to take better jobs.

This shouldn’t be happening in America, and to be fair some politicians in both parties have been speaking up about the need for change (although few expect the Trump administration to follow up on the Obama administration’s reform push). But there’s another aspect of declining worker freedom that is very much a partisan issue: health care.

Until 2014, there was basically only one way Americans under 65 with pre-existing conditions could get health insurance: by finding an employer willing to offer coverage. Some employers were in fact willing to do so. Why? Because there were major tax advantages — premiums aren’t counted as taxable income — but to get those advantages employer plans must offer the same coverage to every employee, regardless of medical history.

But what if you wanted to change jobs, or start your own business? Too bad: you were basically stuck (and I knew quite a few people in that position).

Then Obamacare went into effect, guaranteeing affordable care even to those with pre-existing medical conditions. This was a hugely liberating change for millions. Even if you didn’t immediately take advantage of the new program to strike out on your own, the fact was that now you could.

But maybe not for much longer. Trumpcare — the American Health Care Act — would drastically reduce protections for Americans with pre-existing conditions. And even if that bill never becomes law, the Trump administration is effectively sabotaging individual insurance markets, so that in many cases Americans who lose employer coverage will have no place to turn — which will in turn tie those who do have such coverage to their current employers.

You might say, with only a bit of hyperbole, that workers in America, supposedly the land of the free, are actually creeping along the road to serfdom, yoked to corporate employers the way Russian peasants were once tied to their masters’ land. And the people pushing them down that road are the very people who cry “freedom” the loudest.

A Vital Drug Runs Low, Though Its Base Ingredient Is in Many Kitchens

by Katie Thomas - NYT - May 21, 2017

Hospitals around the country are scrambling to stockpile vials of a critical drug — even postponing operations or putting off chemotherapy treatments — because the country’s only two suppliers have run out.

The medicine? Sodium bicarbonate solution. Yes, baking soda.

Sodium bicarbonate is the simplest of drugs — its base ingredient, after all, is found in most kitchen cabinets — but it is vitally important for all kinds of patients whose blood has become too acidic. It is found on emergency crash carts and is used in open-heart surgery and as an antidote to certain poisons. Patients whose organs are failing are given the drug, and it is used in some types of chemotherapy. A little sodium bicarbonate can even take the sting out of getting stitches.

“As I talk to colleagues around the country, this is really a problem we’re all struggling with right now,” said Mark Sullivan, the head of pharmacy operations at Vanderbilt University Hospital and Clinics in Nashville.

Hospitals have been struggling with a dwindling supply of the medicine for months — one of the suppliers, Pfizer, has said that it had a problem with an outside supplier but that the situation worsened a few weeks ago. Pfizer and the other manufacturer, Amphastar, have said they don’t know precisely when the problem will be fixed, but it will not be before June for some forms of the drug, and in August or later for other formulations.

The shortage of sodium bicarbonate solution is only the latest example of an inexpensive hospital staple’s supply dwindling to a critical level. In recent years, hundreds of generic injectable drugs have become scarce, vexing hospital administrators and government officials, who have called on the manufacturers to give better notice when they are about to run short.

Without an abundant supply of sodium bicarbonate, some hospitals are postponing elective procedures or making difficult decisions about which patients merit the drug. At Providence Hospital in Mobile, Ala., supplies ran so low a few weeks ago that Gino Agnelly, the head pharmacist, embarked on a desperate scavenger hunt, culling vials from the 50 crash carts that were stowed around the hospital.

Mr. Agnelly said he had been getting by with a supply of about 175 vials when a patient with a heart problem suddenly needed 35 of them.

He called a meeting of doctors and administrators, and they came to a difficult conclusion: They would need to postpone the seven open-heart operations that were scheduled for the next week. One critically ill patient was sent to a hospital across town because his surgery could not be delayed, Mr. Agnelly said.

Pfizer sent an emergency shipment a few days later, but the continuing shortage has forced Mr. Agnelly to make hard choices.

“Does the immediate need of a patient outweigh the expected need of a patient?” he asked. “It’s a medical and ethical question that goes beyond anything I’ve had to experience before.”

Erin Fox, a drug shortage expert at the University of Utah, said unexpected shortfalls of critical medicines had become routine. In 2014, a shortage of saline solution — salt water — sent hospitals into a similar panic. This is not even the first time that the supply of sodium bicarbonate has run out. The last shortage occurred in 2012.

“It is unbelievably frustrating,” Ms. Fox said. “It makes me so mad that we are out of these really basic lifesaving medications.”

Mr. Sullivan, of Vanderbilt, said the shortages typically occurred with cheaper, “bread-and-butter” hospital drugs, leading him to question whether manufacturers were investing enough in the production process needed to make a reliable supply.

“The specialty, high-dollar medicines — I don’t ever seem to see them experiencing shortages with those products,” he said.

The situation with sodium bicarbonate solution appears to have begun in February when Pfizer, the main supplier, announced it was in short supply, Ms. Fox said. A spike in demand then led Amphastar to run low. Now, even less-than-ideal alternatives to sodium bicarbonate, such as sodium acetate, are difficult to obtain.

Kuldip Patel, the associate chief pharmacy officer at Duke University Hospital in North Carolina, said he had become accustomed to the juggling act required when an old standby was suddenly unavailable.

“It’s not like we haven’t been here before,” he said.

Mr. Patel said the problem had worsened just after Pfizer went from shipping its generic injectable products from five regional warehouses to one national distribution center, part of a reorganization after its acquisition of the drugmaker Hospira.

“That’s when it all derailed,” he said.

A spokesman for Pfizer said the shortage of sodium bicarbonate was not related to the change in distribution, but was due to a manufacturing delay caused by an outside supplier. The spokesman, Thomas Biegi, said the delay had not been caused by a problem with the supplier of the raw ingredient, sodium bicarbonate, but he added that he could not divulge further details, citing confidentiality agreements.

Regardless of the reason, Mr. Patel said, drug companies should do a better job of creating contingency plans for keeping vital drugs in supply, especially during transitions.

“In situations like this, where a major manufacturer is buying out another major manufacturer of critically needed drugs, there has to be a detailed backup plan in case things don’t go smoothly,” Mr. Patel said.

Mr. Biegi said Pfizer was working hard to fix the problem. “Pfizer has a dedicated team focused on working with suppliers to address this and have already taken several steps to expedite supply recovery of this drug,” he said.

Andrea Fischer, a spokeswoman for the Food and Drug Administration, said companies were asked to notify the agency of problems, but “there are no requirements that firms keep emergency supplies or that they stock up prior to any changes they make.”

She said the agency was in close contact with the companies and “exploring all possible solutions to this critical shortage, including temporary importation, to help with this shortage until it’s resolved.”

Ms. Fischer said the agency had recently made progress in preventing supply problems. In 2011, it tracked 251 new shortages, an all-time high. But by 2016, she said, there were only 23 new shortages. Currently, more than 50 drugs are classified as being in shortage on the F.D.A. website.

“Unfortunately,” she said, “not all shortages can be prevented.”

The shortage problem has been traced to a confluence of factors, ranging from problems with suppliers of the raw ingredients to trouble at the aging facilities where many of the most inexpensive generics are made. Consolidation in the industry has also reduced the number of companies producing certain drugs, so that when one company has a problem, the other quickly runs out as well.

Ms. Fischer said the F.D.A. gave the approval process a priority status when a company wanted to enter a market that was in short supply.

Some large hospitals, such as Duke, house so-called compounding pharmacies, which can make custom batches of generics like sodium bicarbonate. Mr. Patel said that Duke was in the process of doing just that, but that setting up the process took time. The solution must be pure and sterile because it is injected into the bloodstream.

At Providence Hospital in Mobile, Mr. Agnelly said he was so desperate that he had done an internet search to investigate if he could safely mix his own batch with some baking soda and water. The hospital does not have a compounding pharmacy.

He discovered just one research paper, dating to 1947, when doctors did exactly that during World War II.

“This is not new technology. These are not expensive materials,” Mr. Agnelly said, adding that he quickly abandoned the idea. “It’s not what you would expect in the First World.”

The Health 202: Trump is behaving to insurers like a commitment-phone

by Page Winfield Cunningham - The Washington Post - May 22, 217

President Trump is playing coy with insurers who want an “I do” from him on getting billions of dollars of extra subsidy payments for low-income people under the Affordable Care Act. The insurers are threatening to break up with the Obamacare marketplaces without a long-term commitment from his administration that they’ll get the money.

Late last week, the White House told us that it will pony up in May. But it isn’t committing to making any of the payments beyond this month. A spokesman told me that no final decisions have yet been made, and all options are on the table.

But what insurers need is certainty as they price their plans for next year and try to decide whether they’ll even be able to afford selling ACA marketplace coverage at all – not for Trump to put them on a month-to-month subsidy payment plan.

(A quick explanation of what we’re talking about here. These federal subsidies are different from the tax credits to help people pay their monthly premium for Obamacare marketplace plans. Known as cost-sharing reductions, the payments reimburse insurers for discounting to low-income people the extra costs associated with a plan – such as a co-payment for a prescription drug. Insurers must provide the discounts, even if they’re not reimbursed by the feds.)

Today is a key date in the saga. The Trump administration must indicate to the U.S. Court of Appeals in D.C. how it wants to handle an ongoing lawsuit over the subsidy payments. The Health 202 (and many in Washington, for that matter) will be watching closely, because things could go a number of different ways.

It's also the beginning of what's likely to be a wild week in health-care politics on Capitol Hill. The Congressional Budget Office is expected to release its score of the latest House health measure (rumors are that will happen Wednesday), which will reveal whether the bill saves enough money to be considered under special budget rules designed to subject it to a simple-majority vote in the Senate. This score will be used to decide whether the American Health Care Act complies with overall rules allowing it to be considered under "reconciliation."

But back to the subsidies. Most of the scenarios regarding them don’t look great for insurers or the stability of the marketplaces where the insurer exits and rate hikes of last year may be even more pronounced next year. There’s been a cascade of bad news in the past month, including Aetna’s announcement that it’s withdrawing completely and early insurer requests in Connecticut, Maryland, Virginia and New York to hike rates dramatically.

Trump, who has gleefully predicted an eventual demise for President Obama’s health-care law, is in a strange predicament. A court has ruled that the federal government can’t pay out the subsidies without permission from Congress – and last month, Congress refused to allocate the funds.

So now things are up to him, and there are some indications he doesn't want to make the payments. Trump told aides last Tuesday that he wants to end them because he doesn't gain anything by continuing them, according to a report from Politico. "Why the hell would we?" he said, according to an adviser. Trump has also made statements in the past few months indicating he's on the fence, like when he suggested to The Economist he could stop paying them when he wanted to.

Here are a few ways this all could play out and what it would mean for insurers:

--Worst-case for insurers: The administration drops the appeal. This causes the most chaos for insurers, since the original ruling would stand and Trump couldn’t legally fund the payments without consent from Congress.

--Best-case for insurers: The administration continues the appeal begun by the Obama administration. While they’d still have long-term uncertainty, Trump could keep making the payments in the short-term. And it would be difficult for him to stop them because that would undercut his legal position.

--Not great for insurers: The administration asks the court for more time to figure out its next moves and the judge grants it. Insurers are stuck in limbo for the next few months with no more certainty about whether they’ll get the payments long-term.

--Maybe okay for insurers: The administration asks the court for more time and the judge says no. Insurers get resolution sooner because the administration is forced to come back in a short time frame with a decision.

Let’s be clear: The Obamacare marketplaces in some states are likely headed for deep trouble, even with these subsidy payments. But without them, the road ahead gets even steeper for insurers, who would have to eat the losses or otherwise massively hike premiums (some estimates have said by 19 percent).

If you look at the whole pie of federal payments that marketplace insurers are expecting this year (that includes billions of dollars for premiums), the cost-sharing subsidies comprise a pretty big slice – about $7 billion, or 15 percent of all subsidies. So losing out on those payments could seriously hurt plans, jeopardizing the ability of potentially millions of Americans to get health coverage under Trump’s watch.

It will be fascinating to watch how Trump moves on this. If his administration appeals the court’s ruling, it puts the Republican-run White House at odds with the Republican-led House (when the House originally filed the lawsuit several years ago, it was against the Obama administration). But if the administration allows the ruling to stand, Trump couldn’t legally pay out the subsidies, dealing a huge blow to insurers in the Obamcare marketplaces.

We'll be watching.

Is big government bad for freedom, civil society, and happiness?

by Lane Kentworthy - The Good Society - May, 2017

Public goods, services, and transfers boost living standards, reduce insecurity, improve health, and equalize opportunity.1 But in the course of achieving these valuable goals, do government programs impinge on freedom, weaken civil society, and reduce happiness?

Critics of modern government often assert that they do. “The state can gravely threaten the space for private life,” says Yuval Levin. “It can do so,” he explains, “by invading that space and attempting to fill it, and by collapsing that space under the weight of government’s sheer size, scope, and cost. Both dangers have grown grave and alarming in our time.”2 Several decades earlier, Milton and Rose Friedman warned of a “major evil” of public social programs: “their effect on the fabric of our society. They weaken the family … and limit our freedom.”3

FREEDOM

Because they are funded mainly by taxes, government programs restrict people’s ability to do what they wish with their income, and in this sense government plainly does reduce freedom.4 By how much? Figure 1 shows effective tax rates in the United States for households at various points along the pretax income distribution. An “effective tax rate” is calculated as taxes paid divided by pretax income. Americans with pretax incomes in the bottom fifth pay, on average, about 20% of their income in taxes. Those with incomes in the middle pay about 27%. Those at the top (in the top 1%) pay about 33%. Whether this constitutes a significant curtailment of freedom is in the eye of the beholder.

Figure 1. Effective tax rates in the United States

Taxes paid as a share of pretax income. The tax rates are averages for the following groups: p0-20, p40-60, p60-80, p80-90, p90-95, p95-99, p100 (top 1%). Includes all types of taxes (personal and corporate income, payroll, property, sales, excise, estate, other) at all levels of government (federal, state, local). The data are for 2015. Data source: Citizens for Tax Justice, “Who Pays Taxes in America in 2015?,” using data from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Taxes paid as a share of pretax income. The tax rates are averages for the following groups: p0-20, p40-60, p60-80, p80-90, p90-95, p95-99, p100 (top 1%). Includes all types of taxes (personal and corporate income, payroll, property, sales, excise, estate, other) at all levels of government (federal, state, local). The data are for 2015. Data source: Citizens for Tax Justice, “Who Pays Taxes in America in 2015?,” using data from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

The more interesting question is whether government impinges on freedom in other respects. Three are of particular interest.

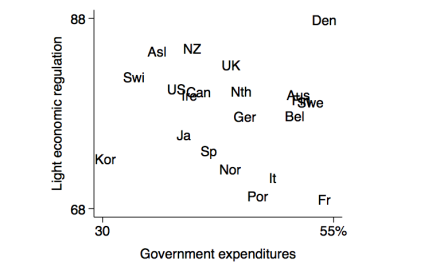

It is sometimes assumed that a government overseeing an expansive and generous set of public social programs will inevitably also exert a heavy regulatory hand, limiting the freedom of firms and workers to make decisions in pursuit of their interests.5 Figure 2 shows that, among the world’s rich longstanding-democratic nations, that assumption is wrong. On the vertical axis is each country’s average score for five types of “economic freedom” — the absence of heavy regulation — according to the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. On the horizontal axis is government spending as a share of GDP. Higher-spending nations don’t tend to be heavier regulators.

Figure 2. Government size and light economic regulation

Light economic regulation: average score for business freedom, labor freedom, trade freedom, investment freedom, and financial freedom. Scale is 0 to 100. The data are for 2016. Data source: Heritage Foundation, heritage.org/index. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average over 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.11.

Light economic regulation: average score for business freedom, labor freedom, trade freedom, investment freedom, and financial freedom. Scale is 0 to 100. The data are for 2016. Data source: Heritage Foundation, heritage.org/index. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average over 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.11.

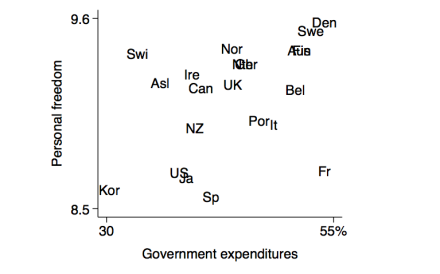

What about freedoms for ordinary individuals? Does a big-taxing and -spending government reduce our ability to pursue the kind of life we wish to lead? The Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, has assembled a “personal freedom index” that measures legal protection, security, freedom of movement, freedom of religion, freedom of association, assembly, and civil society, freedom of expression, and freedom in relationships. Figure 3 suggests no incompatibility between big government and individual liberty.

Figure 3. Government size and personal freedom

Personal freedom: average score for legal protection, security, freedom of movement, freedom of religion, freedom of association, assembly, and civil society, freedom of expression, and freedom in relationships. Scale is 0 to 10. 2012. Data source: Ian Vasquez and Tanja Porcnik, The Human Freedom Index, Cato Institute, 2015, table 2. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average over 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.40.

Personal freedom: average score for legal protection, security, freedom of movement, freedom of religion, freedom of association, assembly, and civil society, freedom of expression, and freedom in relationships. Scale is 0 to 10. 2012. Data source: Ian Vasquez and Tanja Porcnik, The Human Freedom Index, Cato Institute, 2015, table 2. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average over 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.40.

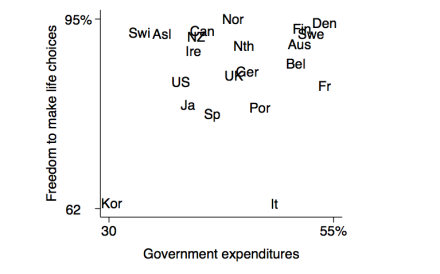

An additional source of information about freedom is public opinion surveys. Since 2005 the Gallup World Poll has asked a representative sample of adults in various countries whether they are satisfied or dissatisfied with their freedom to choose what they do with their life. The vertical axis in figure 4 shows the share responding “satisfied” in each country. As the figure reveals, citizens in countries with heavier government expenditure totals aren’t more likely to see their lives as constrained or limited.

Figure 4. Government size and freedom to make life choices

Freedom to make life choices: share responding “satisfied” to the question “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?” Data source: Gallup World Poll, via the World Happiness Report 2017, online appendix. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Average over 2000-2014. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.22.

Freedom to make life choices: share responding “satisfied” to the question “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?” Data source: Gallup World Poll, via the World Happiness Report 2017, online appendix. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Average over 2000-2014. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.22.

Indeed, government programs often enhance freedom. Anu Partanen’s comparison of her native Finland with her adopted country, the United States, highlights this point. Partanen finds that many Americans don’t have access to high-quality, affordable health insurance, child care, housing in good school districts, college, and senior care. This, she points out, diminishes not only Americans’ security but also their freedom6:

“Most people, including myself, assumed that part of what made the United States a great country, and such an exceptional one, was that you could live your life relatively unencumbered by the downside of a traditional, old-fashioned society: dependency on the people you happened to be stuck with. In America you had the liberty to express your individuality and choose your own community. This would allow you to interact with family, neighbors, and fellow citizens on the basis of who you were, rather than on what you were obligated to do or expected to be according to old-fashioned thinking. The longer I lived in America … the more puzzled I grew. For it was exactly those key benefits of modernity — freedom, personal independence, and opportunity — that seemed, from my outsider’s perspective, in a thousand small ways to be surprisingly missing from American life today…. In order to compete and to survive, the Americans I encountered and read about were … beholden to their spouses, parents, children, colleagues, and bosses in ways that constrained their own liberty.”

CIVIL SOCIETY

Another worry about big government is that it will erode or discourage intermediary institutions such as families, voluntary organizations, and perhaps even friendship bonds.

One view about how this plays out is offered by Charles Murray, who links it to happiness7:

“Happiness consists of lasting and justified satisfaction with life as a whole…. Once you start to think through the kinds of accomplishments that lead people to reach old age satisfied with who they have been and what they have done, you will find (…) that the accomplishments you have in mind have three things in common. First, the source of satisfaction involves something important. We can get pleasure from trivial things, but pleasure is different from deep satisfaction. Second, the source of satisfaction has involved effort, probably over an extended period of time. The cliche ‘Nothing worth having comes easily’ is true. Third, some level of personal responsibility for the outcome is essential….“When the government intervenes to help, whether in the European welfare state or in America’s more diluted version, it not only diminishes our responsibility for the desired outcome, it enfeebles the institutions through which people live satisfying lives. There is no way for clever planners to avoid it. Marriage is a strong and vital institution not because the day-to-day work of raising children and being a good spouse is so much fun, but because the family has responsibility for doing important things that won’t get done unless the family does them. Communities are strong and vital not because it’s so much fun to respond to our neighbors’ needs, but because the community has the responsibility for doing important things that won’t get done unless the community does them…. When the government says it will take some of the trouble out of doing the things that families and communities evolved to do, it inevitably takes some of the action away from families and communities….“Europe has proved that countries with enfeebled family, vocation, community, and faith can still be pleasant places to live. I am delighted when I get a chance to go to Stockholm or Paris. When I get there, the people don’t seem to be groaning under the yoke of an oppressive system. On the contrary, there’s a lot to like about day-to-day life in the advanced welfare states of western Europe. They are great places to visit. But the view of life that has taken root in those same countries is problematic. It seems to go something like this: The purpose of life is to while away the time between birth and death as pleasantly as possible, and the purpose of government is to make it as easy as possible to while away the time as pleasantly as possible — the Europe Syndrome.“Europe’s short workweeks and frequent vacations are one symptom of the syndrome. The idea of work as a means of self-actualization has faded. The view of work as a necessary evil, interfering with the higher good of leisure, dominates. To have to go out to look for a job or to have to risk being fired from a job are seen as terrible impositions. The precipitous decline of marriage, far greater in Europe than in the United States, is another symptom. What is the point of a lifetime commitment when the state will act as surrogate spouse when it comes to paying the bills? The decline of fertility to far below replacement is another symptom. Children are seen as a burden that the state must help shoulder, and even then they’re a lot of trouble that distract from things that are more fun.”

This is a plausible hypothesis (or set of hypotheses). Let’s start with family. It’s conceivable that by reducing the need to have a partner to help with the breadwinning and childrearing, government services and transfers will cause fewer people to commit to long-term family relationships. But if so, we might expect family to have weakened considerably when universal K-12 schooling (kindergarten, elementary, and secondary) was established, and that didn’t happen. Still, perhaps adding paid parental leave, child care, preschool, a child allowance, and other government supports has pushed the big-government countries past the tipping point.

What do the cross-country data tell us? Marriage isn’t a helpful indicator here. The institution has fallen out of favor in many western European countries, but that doesn’t necessarily mean there are fewer long-term relationships. A better measure is the share of children living in a home with two parents. Figure 5 has this on the vertical axis, with government expenditures as a share of GDP on the horizontal axis. According to this measure, family isn’t weaker in countries with bigger governments.

Figure 5. Government size and two-parent households

Children in two-parent households: share of children age 0 to 14 who live in a household with both a mother and father. 2014. Data source: OECD Family Database, table SF1.3.A. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.12.

Children in two-parent households: share of children age 0 to 14 who live in a household with both a mother and father. 2014. Data source: OECD Family Database, table SF1.3.A. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.12.

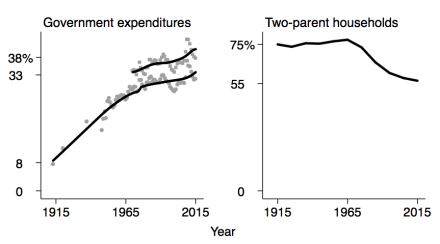

For the United States, we have data going back to the early twentieth century for a comparable measure — the share of children living with both of their biological parents at age 16 (and thus likely throughout their childhood). Figure 6 shows the over-time pattern, along with that for government expenditures as a share of GDP. Government size increased steadily from the early 1900s until the mid-1960s. Since then it has continued to grow, but at a much slower pace. During the years in which government size was increasing, the share of children growing up with both parents held steady at about 75%. In the mid-1960s it began to decline, falling to about 55% in the 2010s.

This isn’t what we would expect to observe if big government is a major contributor to family decline. It’s conceivable that government size reached a tipping point around 1960 or 1965, sending family stability on a downward path thereafter even though there was little additional rise in government expenditures. But it seems unlikely that the United States reached such a tipping point given that many countries with bigger governments have more two-parent households (figure 5).

Figure 6. Government size and two-parent households in the United States

Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: federal, state, and local. The lines are loess curves. Data sources the lower line: for pre-1948, Vito Tanzi, Government versus Markets, Cambridge University Press, 2011, table 1.1; for 1948ff, Economic Report of the President, various years. Data source for the upper line: OECD. Two-parent households: share of children living with both biological parents at age 16. Decade averages. Data source: General Social Survey, sda.berkeley.edu, series family16.

Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: federal, state, and local. The lines are loess curves. Data sources the lower line: for pre-1948, Vito Tanzi, Government versus Markets, Cambridge University Press, 2011, table 1.1; for 1948ff, Economic Report of the President, various years. Data source for the upper line: OECD. Two-parent households: share of children living with both biological parents at age 16. Decade averages. Data source: General Social Survey, sda.berkeley.edu, series family16.

Have people in big-government countries stopped having kids? According to Murray, expansive and generous public social programs foster a culture in which children are seen as a burden and a distraction from the fun things in life. This too turns out to be wrong, as figure 7 shows. Across the rich democratic countries, there is no association between government size and fertility.

Figure 7. Government size and fertility

Fertility rate: average number of children born per woman. 2014. Data source: OECD Family Database, chart SF2.1.A. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.21.

Fertility rate: average number of children born per woman. 2014. Data source: OECD Family Database, chart SF2.1.A. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.21.

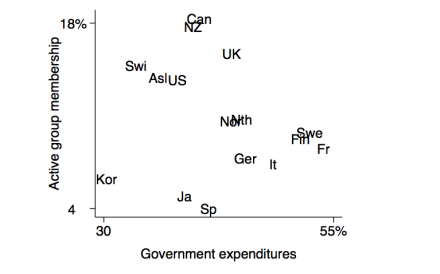

What about participation in voluntary organizations? Yuval Levin contends that “progressive social policy … has sought to make civil society less essential by assigning to the state many of the roles formerly played by religious congregations, civic associations, fraternal groups, and charities, especially in providing help to the poor.”8 Historically, Americans have been prolific participators.9 Is that because the United States has fewer and stingier public insurance programs than most other affluent countries? In figure 8 we see a negative association across the rich countries between government spending and the share of adults who say they are an active member of a civic group or organization, but the association is quite weak.

Consider the United States and Sweden, two countries that contrast sharply in the expansiveness and generosity of their public insurance programs. If big government has the effect of quashing or crowding out civic engagement, we ought to observe significantly more participation in civic groups by Americans than by Swedes. The World Values Survey asks about active membership in eight types of groups: religious, sports-recreation, art-music-education, charitable, professional, labor union, environmental, and consumer. Each country has been surveyed three times over the past two decades. It turns out the difference between the two countries is fairly small. When we average across these eight types of groups, 10% of Swedes say they are active members compared to 14% of Americans. And that small difference owes heavily to religious groups, with only 6% of Swedes reporting active membership compared to 36% of Americans.

Figure 8. Government size and civic engagement

Active group membership: share of adults who say they are an active member of a civic group or organization. Average for eight types of organization: religious, sports-recreation, art-music-education, charitable, professional, labor union, environmental, consumer. Question: “Now I am going to read off a list of voluntary organizations. For each organization, could you tell me whether you are an active member, an inactive member, or not a member of that type of organization?” The data are for 2005-2014. Data source: World Values Survey, worldvaluessurvey.org. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia. The correlation is -.21.

Active group membership: share of adults who say they are an active member of a civic group or organization. Average for eight types of organization: religious, sports-recreation, art-music-education, charitable, professional, labor union, environmental, consumer. Question: “Now I am going to read off a list of voluntary organizations. For each organization, could you tell me whether you are an active member, an inactive member, or not a member of that type of organization?” The data are for 2005-2014. Data source: World Values Survey, worldvaluessurvey.org. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia. The correlation is -.21.

Robert Putnam has compiled data on membership rates in 32 national chapter-based associations that existed throughout much of the twentieth century in the United States. Figure 9 shows that the era when government expanded the most sharply, between 1915 and 1965, was also was the heyday of rising civic participation. The subsequent decline of civic engagement occurred during a period when government size increased much more slowly.

Figure 9. Government size and civic engagement in the United States

Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: federal, state, and local. The lines are loess curves. Data sources the lower line: for pre-1948, Vito Tanzi, Government versus Markets, Cambridge University Press, 2011, table 1.1; for 1948ff, Economic Report of the President, various years. Data source for the upper line: OECD. Organization membership: includes the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, 4-H, League of Women Voters, Knights of Columbus, Rotary, Elks, Kiwanis, Jaycees, Optimists, American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the NAACP, B’nai B’rith, Grange, Red Cross, and more. Data source: Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Simon and Schuster, 2000, figure 8.

Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: federal, state, and local. The lines are loess curves. Data sources the lower line: for pre-1948, Vito Tanzi, Government versus Markets, Cambridge University Press, 2011, table 1.1; for 1948ff, Economic Report of the President, various years. Data source for the upper line: OECD. Organization membership: includes the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, 4-H, League of Women Voters, Knights of Columbus, Rotary, Elks, Kiwanis, Jaycees, Optimists, American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the NAACP, B’nai B’rith, Grange, Red Cross, and more. Data source: Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Simon and Schuster, 2000, figure 8.

Government programs surely have some effect of reducing participation in voluntary groups and organizations. But that effect looks unlikely to be very large.

Even if modern big government does crowd out some intermediary organizations, it’s worth asking whether that is bad. Consider safety and property protection. This can be provided by voluntary intermediary organizations, such as local militias. But it’s done more effectively and fairly (because rules assure that everyone gets access to the service, the accused have rights, and so on) by a government police force. Similarly, voluntary “savings clubs” might help to address the problem of people setting too little aside for retirement. But it’s much more effective and efficient to create a government pension program such as Social Security. The point here isn’t that public programs are always better. In some instances they are, and in others they aren’t. The point is that we shouldn’t fetishize civic engagement. Less of it isn’t always a societal loss.

What about family and groups as a source of social support? Yuval Levin suggests that “As the national government grows more centralized, and takes over the work otherwise performed by mediating institutions — from families and communities to local governments and charities — individuals become increasingly atomized.”10 One measure comes from the Gallup World Poll, which regularly asks “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?” The comparative pattern, shown in figure 10, suggests no adverse impact of big government.

Figure 10. Government size and social support

Social support: share responding yes to the question “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?” Average over 2005-2016. Data source: Gallup World Poll, via the World Happiness Report 2017, online appendix. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.22 (excluding South Korea).

Social support: share responding yes to the question “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?” Average over 2005-2016. Data source: Gallup World Poll, via the World Happiness Report 2017, online appendix. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.22 (excluding South Korea).

According to Levin, in the United States “we have set loose a scourge of loneliness and isolation,” partly as a consequence of government expansion and its purported impact on civil society.11 Yet the most thorough look at available data on isolation and loneliness in the US, by Claude Fischer, concludes that neither has in fact increased.12

HAPPINESS

In Charles Murray’s view, big government tends to reduce happiness. According to the hypothesis, this happens partly via a weakening of families and civil society. As we’ve just seen, the evidence doesn’t support this worry.

Another potential pathway is employment. In European nations with cushy welfare states, says Murray, “the idea of work as a means of self-actualization has faded. The view of work as a necessary evil, interfering with the higher good of leisure, dominates. To have to go out to look for a job or to have to risk being fired from a job are seen as terrible impositions.” Here too the data say otherwise. Figure 11 suggests no association between the size of government and the share of the working-age population in paid employment.13

Figure 11. Government size and employment

Employment rate: employed persons age 25-64 as a share of the population age 25-64. The data are for 2015. Data source: OECD. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.13.

Employment rate: employed persons age 25-64 as a share of the population age 25-64. The data are for 2015. Data source: OECD. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average for 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is -.13.

So Murray’s hypothesized pathways through which big government might reduce happiness — family, civil society, employment — don’t pan out in the real world. Is there, however, a direct effect? If government supports and cushions take too much of the struggle out of life, perhaps we’ll feel too little sense of accomplishment to be genuinely happy.

The first thing to note here is that where government has made life easier, that usually has been a good thing. Think of protection of life and property, clean water, clean air, sewage and trash removal, roads, parks, and schooling, among many others. Second, technological advance and private enterprise have done as much as government, and probably a good bit more, to take the trouble out of life. Few of us any longer grow or hunt our food, make our clothes, build the house we live in, and so on. Nor do we have to walk or ride a horse to get to work, wash clothes and dishes by hand, or go to a library to get answers to important questions.

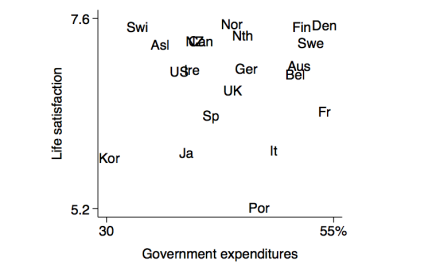

Still, it’s conceivable that there is a point beyond which happiness might decline because government makes life too easy. Have existing countries reached such a point? Figure 12 suggests they haven’t. The average level of life satisfaction tends to be as high in big-government countries, such as the Nordics, as in those with medium-size governments, such as Switzerland and the United States.14

Figure 12. Government size and life satisfaction

Life satisfaction: average score. Scale is 0 to 10. Question: “Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” Average over 2014-2016. Data source: Gallup World Poll, via the World Happiness Report 2017, online appendix. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average over 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.10.

Life satisfaction: average score. Scale is 0 to 10. Question: “Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” Average over 2014-2016. Data source: Gallup World Poll, via the World Happiness Report 2017, online appendix. Government expenditures: share of GDP. Includes all levels of government: national, regional, local. Average over 2000-2014. Data source: OECD. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The correlation is +.10.

SUMMARY

Do the gains from government goods, services, and transfers come at the cost of reduced freedom, weakened civil society, and diminished happiness? The experience of the world’s affluent democratic countries suggests that, at least so far, the answer is no.

A Global Health Scorecard Finds U.S. Lacking

by Donald McNeil - NYT - May 22, 2017

Over the last 25 years, China, Ethiopia, the Maldive Islands, Peru, South Korea and Turkey had the greatest improvements in “deaths avoidable through health care at their economic level,” a complex but intriguing new measure of global mortalitydescribed last week in the Lancet.

By that standard, the United States improved slightly over the same period, 1990 to 2015. But the American ranking is still so low that it’s “an embarrassment, especially considering the U.S. spends $9,000 per person on health care annually,” said the report’s chief author, Dr. Christopher J. L. Murray, director of the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, created by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Elected officials now struggling to reform American health care, Dr. Murray added, “should take a look at where the U.S. is falling short.”

The new measure takes into account at how well each country — whether rich or poor — fared at preventing deaths that could be avoided by applying known medical interventions. (The metric thus excludes many deaths from epidemics, smoking, obesity, guns, car accidents and so on.)

The report further judged countries relative to how rich they were and how much richer they became from 1990 to 2015. (Some regions, like Latin America, Eastern Europe and parts of Asia, became much wealthier. Africa did not, but its health care delivery benefited from donated vaccines and AIDS drugs, for example.)

Poor countries were judged based on how well they did at simple things, like vaccinating against diphtheria or curing pneumonia. Middle-income countries had to meet higher standards, like successful surgeries for appendicitis and hernia, or treatment for epilepsy and birth problems.

And wealthy countries were judged on all those, plus success at treating breast, colon and skin cancer, diabetes, heart disease and so on.

The highest-ranked countries, besides tiny Andorra, the winner, were Iceland, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway and Australia. The lowest in the rankings were the Central African Republic, Afghanistan and Somalia.

The United States ranked 35th. It ranked worse than many of its peers in curing pneumonia, lymphoma and skin cancer, in managing diabetes and heart disease and in medical mistakes and malpractice.

Some countries, including India, Indonesia and South Africa, got relatively worse at saving their citizens from death even as they got richer.

The price tag on universal health care is in, and it’s bigger than California’s budget

by Angela Hart - Sacramento Bee - May 22, 2017

'Don't wait for them. You lead' on health care, nurses' leader tells rally 1:38

RoseAnn DeMoro, executive director of the California Nurses Association, told hundreds of nurses and health care advocates gathered for a rally at the Capitol that Democrats need to support a public-funded universal health care system in California. Angela Hart ahart@sacbee.com

The price tag is in: It would cost $400 billion to remake California’s health insurance marketplace and create a publicly funded universal heath care system, according to a state financial analysis released Monday.

California would have to find an additional $200 billion per year, including in new tax revenues, to create a so-called “single-payer” system, the analysis by the Senate Appropriations Committee found. The estimate assumes the state would retain the existing $200 billion in local, state and federal funding it currently receives to offset the total $400 billion price tag.

The cost analysis is seen as the biggest hurdle to creating a universal system, proposed by Sens. Ricardo Lara, D-Bell Gardens, and Toni Atkins, D-San Diego.

It remains a long-shot bid. Steep projected costs have derailed efforts over the past two decades to establish such a health care system in California. The cost is higher than the $180 billion in proposed general fund and special fund spending for the budget year beginning July 1.

Employers currently spend between $100 billion to $150 billion per year, which could be available to help offset total costs, according to the analysis. Under that scenario, total new spending to implement the system would be between $50 billion and $100 billion per year.

“Health care spending is growing faster than the overall economy ... yet we do not have better health outcomes and we cover fewer people,” Lara said at Monday’s appropriations hearing. “Given this picture of increasing costs, health care inefficiencies and the uncertainty created by Congress, it is critical that California chart our own path.”

The idea behind Senate Bill 562 is to overhaul California’s insurance marketplace, reduce overall health care costs and expand coverage to everyone in the state regardless of immigration status or ability to pay. Instead of private insurers, state government would be the “single payer” for everyone’s health care through a new payroll taxing structure, similar to the way Medicare operates.

Lara and Atkins say they are driven by the belief that health care is a human right and should be guaranteed to everyone, similar to public services like safe roads and clean drinking water. They seek to rein in rising health care costs by lowering administrative expenses, reducing expensive emergency room visits, and eliminating insurance company profits and executive salaries.

In addition to covering undocumented people, Lara said the goal is to expand health access to people who, even with insurance, may skip doctor visits or stretch out medications due to high copays and deductibles.

“Doctors and hospitals would no longer need to negotiate rates and deal with insurance companies to seek reimbursement,” Lara said.

Insurance groups, health plans and Kaiser Permanente are against the bill. Industry representatives say California should focus on improving the Affordable Care Act. Business groups, including the California Chamber of Commerce, have deemed the bill a “job-killer.”

“A single-payer system is massively, if not prohibitively expensive,” said Nick Louizos, vice president of legislative affairs for the California Association of Health Plans.

“It will cost employers and taxpayers billions of dollars and result in significant loss of jobs in the state,” the Chamber of Commerce said in its opposition letter.

Underlying the debate is uncertainty at the federal level over what President Donald Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress will do with Obamacare. The House Republican bill advanced earlier this month would dismantle it by removing its foundation – the individual mandate that requires everyone to have coverage or pay a tax penalty.

Republican-led efforts to repeal and replace Obamacare is fueling political support for the bill, Atkins said at a universal health care rally this past weekend in Sacramento hosted by the California Nurses Association, a co-sponsor.

“This is a high-ticket expense ... We have to figure out how to cover everyone and work on addressing the costs in the long-term – that’s our challenge,” Atkins said. “I’m optimistic.”

The bill has to get approval on the Senate floor by June 2 to advance to the Assembly. A financing plan is underway, which could suggest diverting money employers pay for workers’ compensation insurance to a state-run coverage system.

Lara said he believes California can and should play a prominent role in improving people’s lives.

“We can do better,” he said.

Trump’s Budget Cuts Deeply Into Medicaid and Anti-Poverty Efforts

by Julie Hirschfeld Davis - NYT - May 22, 2017

WASHINGTON — President Trump plans to unveil on Tuesday a $4.1 trillion budget for 2018 that would cut deeply into programs for the poor, from health care and food stamps to student loans and disability payments, laying out an austere vision for reordering the nation’s priorities.

The document, grandly titled “A New Foundation for American Greatness,” encapsulates much of the “America first” message that powered Mr. Trump’s campaign. It calls for an increase in military spending of 10 percent and spending more than $2.6 billion for border security — including $1.6 billion to begin work on a wall on the border with Mexico — as well as huge tax reductions and an improbable promise of 3 percent economic growth.

The wildly optimistic projections balance Mr. Trump’s budget, at least on paper, even though the proposal makes no changes to Social Security’s retirement program or Medicare, the two largest drivers of the nation’s debt.

To compensate, the package contains deep cuts in entitlement programs that would hit hardest many of the economically strained voters who propelled the president into office. Over the next decade, it calls for slashing more than $800 billion from Medicaid, the federal health program for the poor, while slicing $192 billion from nutritional assistance and $272 billion over all from welfare programs. And domestic programs outside of military and homeland security whose budgets are determined annually by Congress would also take a hit, their funding falling by $57 billion, or 10.6 percent.

The plan would cut by more than $72 billion the disability benefits upon which millions of Americans rely. It would eliminate loan programs that subsidize college education for the poor and those who take jobs in government or nonprofit organizations.

Mr. Trump’s advisers portrayed the steep reductions as necessary to balance the nation’s budget while sparing taxpayers from shouldering the burden of programs that do not work well.

“This is, I think, the first time in a long time that an administration has written a budget through the eyes of the people who are actually paying the taxes,” said Mick Mulvaney, Mr. Trump’s budget director.

“We’re not going to measure our success by how much money we spend, but by how many people we actually help,” Mr. Mulvaney said as he outlined the proposal at the White House on Monday before its formal presentation on Tuesday to Congress.

Among its innovations: Mr. Trump proposes saving $40 billion over a decade by barring undocumented immigrants from collecting the child and dependent care tax credit. He has also requested $19 billion over 10 years for a new program, spearheaded by his daughter and senior adviser Ivanka Trump, to provide six weeks of paid leave to new parents. The budget also includes a broad prohibition against money for entities that provide abortions, including Planned Parenthood, blocking them from receiving any federal health funding

The release of the document, an annual ritual in Washington that usually constitutes a marquee event for a new president working to promote his vision, unfolded under unusual circumstances. Mr. Trump is out of the country for his first foreign trip, and his administration is enduring a near-daily drumbeat of revelations about the investigation into his campaign’s possible links with Russia.

The president’s absence, which his aides dismissed as a mere coincidence of the calendar, seemed to highlight the haphazard way in which his White House has approached its dealings with Congress. It is just as much a sign of Mr. Trump’s lack of enthusiasm for the policy detail and message discipline that is required to marshal support to enact politically challenging changes.

“If the president is distancing himself from the budget, why on earth would Republicans rally around tough choices that would have to be made?” said Robert L. Bixby, the executive director of the Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan organization that promotes deficit reduction. “If you want to make the political case for the budget — and the budget is ultimately a political document — you really need the president to do it. So, it does seem bizarre that the president is out of the country.”