|

|

|

|

|

Opinion Going for-profit is the wrong way to fix Ontario’s health-care crisisby David Moscrop -The Washington Post - January 25, 2023There’s no question that Ontario’s public health-care system is strained — to the point of catastrophe. In November, the average stay in the emergency room for admitted patients in the province was 22.4 hours. The Ontario government says the waiting list for surgical procedures tops 200,000. Last fall, patients in one city were left outside in the ambulance bay for hours waiting to be let into the hospital. Nurses are burned out and quitting or considering quitting in droves. These failures are cruel — and can be deadly. But Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s plan to ease the stress by expanding for-profit medical services is the wrong way to fix the problem. Ford’s plan, unveiled on Jan. 16, will move tens of thousands of cataract surgeries, hip and knee replacements, MRIs, CT scans, colonoscopies, and endoscopies out of hospitals and into for-profit and not-for-profit community facilities. Many critics decry it as a step toward the privatization of public care. It’s not quite that. The plan, whose model exists in one form or another in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Quebec, doesn’t require patients to pay for primary care out-of-pocket — medically necessary services will still be publicly funded — and doesn’t allow wealthy patients to skip the line. David Jacobs, president of the Ontario Association of Radiologists, asserts that the plan is “Health Canada compliant” and “not a for-profit, American-style health care expansion in any way, shape or form.” Nevertheless, it will potentially allow half a billion dollars yearly to flow to private, for-profit facilities. As such, it is a financialization of the medical system, opening it to becoming primarily a financial instrument for investors rather than a public good. Institutional investors who enter the sector will aim to maximize their profits. That most likely means either trying to sell more services to patients or running a leaner, no-frills operation. Or both. The data suggest for-profit care is expensive in more ways than one. A report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives suggests the for-profit shift in British Columbia since 2015 hasn’t solved the province’s health-care woes but has led to unlawful extra-billing and a drain on the public purse. In the United Kingdom, for-profit medical outsourcing has led to an increase in deaths, according to a study published in the Lancet. Ontario has its own analogous data regarding long-term care facilities. The province’s for-profit homes, which account for about 58 percent of the total, had more covid-19 deaths per home than not-for-profit homes. A significant concern is the policy changes will cannibalize the public system by luring away doctors, nurses and technicians with the prospect of more money or better hours. Ford has hand-waved about protecting hospitals by requiring community clinics to provide their staffing plans, but there’s no guarantee that will help. Ford also plans to make it easier for health-care workers from outside the province to practice in Ontario, but that just moves the crisis around. Bringing in practitioners from abroad and training new ones, meanwhile, will take time. There are better ways to deal with this crisis. Moving certain procedures out of hospitals is a good idea, says former Ontario deputy health minister Robert Bell, but they should go to not-for-profit facilities. Danyaal Raza, a family physician and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, agrees. Innovation, he says, would be “taking successes from hospital-associated community surgical centers and making that the standard.” In Ontario, these surgery clinics are efficient, specialized and private not-for-profit hospital extensions that perform procedures outside the hospital — outside the pressures of the profit motive. And they have a track record of getting patients looked after sooner rather than later. The government should also drop its appeal to restore Bill 124, which caps pay increases for public sector workers, including nurses, at 1 percent. It was struck down by the courts in November. “Bill 124 has got to go,” says Birgit Umaigba, a clinical nurse specialist who speaks and writes about nursing from the front lines. The bill, she says, is driving nurses into private facilities — or out of the profession. Umaigba also advocates for speeding up the years-long process to get internationally educated nurses into the system. Further, the province could improve its referral systems. Melanie Bechard, a pediatric emergency physician and chair of Canadian Doctors for Medicare, says a system of family doctors referring patients to a centralized pool of specialists “has been proven to significantly reduce wait times across Canada and the world.” Expanding multidisciplinary medical teams can also help, she notes, by providing patients with treatment from different specialists — physiotherapists, mental health professionals, dietitians and others — as they process through the system, sometimes avoiding the need for procedures or surgeries altogether. None of this requires reinventing the wheel. “We have the right tools for success,” Bechard says. “But we need to expand these models.” Ontario’s health-care system needs reform. It does not need more financialization. Instead, the province ought to reinvest in public and not-for-profit care while expanding best practices. In that space, unlike with doctors and nurses, there is no shortage of ideas that work. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/01/25/ontario-health-care-crisis-for-profit-services/ Government Lets Health Plans That Ripped Off Medicare Keep the Moneyby Fred Schulte - Kaiser Health News - January 30, 2023Medicare Advantage plans for seniors dodged a major financial bullet Monday as government officials gave them a reprieve for returning hundreds of millions of dollars or more in government overpayments — some dating back a decade or more. The health insurance industry had long feared the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services would demand repayment of billions of dollars in overcharges the popular health plans received as far back as 2011. But in a surprise action, CMS announced it would require next to nothing from insurers for any excess payments they received from 2011 through 2017. CMS will not impose major penalties until audits for payment years 2018 and beyond are conducted, which have yet to be started. While the decision could cost Medicare plans billions of dollars in the future, it will take years before any penalty comes due. And health plans will be allowed to pocket hundreds of millions of dollars in overcharges and possibly much more for audits before 2018. Exactly how much is not clear because audits as far back as 2011 have yet to be completed. In late 2018, CMS officials said the agency would collect an estimated $650 million in overpayments from 90 Medicare Advantage audits conducted for 2011 through 2013, the most recent ones available. Some analysts calculated overpayments to plans of at least twice that much for the three-year period. CMS is now conducting audits for 2014 and 2015. The estimate for the 2011-13 audits was based on an extrapolation of overpayments found in a sampling of patients at each health plan. In these reviews, auditors examine medical records to confirm whether patients had the diseases for which the government reimbursed health plans to treat. Through the years, those audits — and others conducted by government watchdogs — have found that health plans often cannot document that they deserved extra payments for patients they said were sicker than average. The decision to take earlier audit findings off the table means that CMS has spent tens of millions of dollars conducting audits as far back as 2011 — much more than the government will be able to recoup. In 2018, CMS said it pays $54 million annually to conduct 30 of the audits. Without extrapolation for years 2011-17, CMS won’t come near to recouping that much. CMS Deputy Administrator Dara Corrigan called the final rule a “commonsense approach to oversight.” Corrigan said she did not know how much money would go uncollected from years prior to 2018. Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra said the rule takes “long overdue steps to move in the direction of accountability.” “Going forward, this is good news. We should all be happy that they are doing that [extrapolation],” said former CMS official Ted Doolittle. But he added: “I do wish they were pushing back further [and extrapolating earlier years]. That would seem to be fair game,” he said. David Lipschutz, an attorney with the Center for Medicare Advocacy, said he was still evaluating the rule, but noted: “It is our hope that CMS would use everything within their discretion to recoup overpayments made to Medicare Advantage plans.” He said that “it is unclear if they are using all of their authority.” Mark Miller, who is the executive vice president of health care policy for Arnold Ventures and formerly worked at the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, a congressional advisory board, said extrapolating errors found in medical coding have always been a part of government auditing. “It strikes me as ridiculous to run a sample and find an error rate and then only collect the sample error rate as opposed to what it presents to the entire population or pool of claims,” he said. (KHN receives funding support from Arnold Ventures.) Last week, KHN released details of the 90 audits from 2011-2013, which were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. The audits found about $12 million in net overpayments for the care of 18,090 patients sampled for the three-year period. In all, 71 of the 90 audits uncovered net overpayments, which topped $1,000 per patient on average in 23 audits. CMS paid the remaining plans too little on average, anywhere from $8 to $773 per patient, the records showed. Since 2010, the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services has threatened to crack down on billing abuses in the popular health plans, which now cover more than 30 million Americans. Medicare Advantage, a fast-growing alternative to original Medicare, is run primarily by major insurance companies including Humana, UnitedHealthcare, Centene, and CVS/Aetna. But the industry has succeeded in opposing extrapolation of overpayments, even though the audit tool is widely used to recover overcharges in other parts of the Medicare program. That has happened despite dozens of audits, investigations, and whistleblower lawsuits alleging that Medicare Advantage overcharges cost taxpayers billions of dollars a year. Corrigan said Monday that CMS expected to collect $479 million from overpayments in 2018, the first year of extrapolation. Over the next decade, it could recoup $4.7 billion, she said. Medicare Advantage plans also face potentially hundreds of millions of dollars in clawbacks from a set of unrelated audits conducted by the Health and Human Services inspector general. The audits include an April 2021 review alleging that a Humana Medicare Advantage plan in Florida had overcharged the government by nearly $200 million in 2015. Carolyn Kapustij, the Office of the Inspector General’s senior adviser for managed care, said the agency has conducted 17 such audits that found widespread payment errors — on average 69% for some medical diagnoses. In these cases, the health plans “did not have the necessary support [for these conditions] in the medical records, which has caused overpayments.” “Although the MA organizations usually disagreed with us, they almost always had little disagreement with our finding that their diagnoses were not supported,” she said. While CMS has taken years to conduct the Medicare Advantage audits, it also has faced criticism for permitting lengthy appeals that can drag on for years. These delays have drawn sharp criticism from the Government Accountability Office, the watchdog arm of Congress. Leslie Gordon, an acting director of the GAO health team, said that until CMS speeds up the process, it “will fail to recover improper payments of hundreds of millions of dollars annually.” KHN senior correspondent Phil Galewitz contributed to this report. Bill would extend MaineCare health coverage to all low-income noncitizensby Randy Billings - Portland Press Herald - January 25, 2023House Speaker Rachel Talbot Ross, D-Portland, has proposed a bill that would give low-income noncitizens access to public health benefits through the state’s MaineCare program. The proposal is likely to draw opposition from Republicans, who have proposed rolling back welfare benefits. Talbot Ross sponsored a similar bill in the last legislative session, but it died in committee after Gov. Janet Mills included a more limited expansion in her supplemental budget that extended MaineCare benefits to pregnant women and people under the age of 21, regardless of citizenship. Other noncitizens were excluded. Talbot Ross said in a written statement provided by a spokesperson that expanding health coverage to all noncitizen residents is both an economic and moral imperative to ensure all Mainers are treated fairly. She said adequate and affordable health care is a “basic fundamental human right.” “Regular, predictable medical treatment is proven to ensure folks can go to work, get to school and take care of their families,” she said. “My legislation seeks to remove barriers, improve outcomes and ensure that all people be treated with dignity and compassion – regardless of how long they have lived in Maine.” Advocates say that preventive care is less expensive than emergency care and ensuring that all Maine workers, including noncitizens who have work permits, is vitally important, especially amid the state’s workforce shortage. Democrats controlled both legislative chambers last session, plus the Blaine House, and could have passed the bill without Republican support. But such a move would have been fodder for Republicans during an election year in which Democrats were facing national headwinds. Neither Talbot Ross, nor spokespeople for Mills, responded to questions about why MaineCare was expanded only to pregnant mothers and those under the age of 21. The Office of Family Independence in the Department of Health and Human Services testified neither for nor against last session’s bill. The governor’s office did not respond to a request for Mills’ position on Talbot Ross’ new bill, L.D. 199. House and Senate Republican leaders said Tuesday that they had not seen the text of the bill, which has been printed but not yet referred to a committee. Instead, they advocated for national immigration reforms, including making it easier for some noncitizens to work and provide for themselves and their families. “I don’t think our caucus is going to be generally supportive of this idea,” said Senate Minority Leader Trey Stewart, R-Presque Isle, adding that he hasn’t yet spoken to members. “I’m all for a safety net for those that need it, but that safety net in Maine has become a hammock and we need to move away from that model.” House Minority Leader Billy Bob Faulkingham, R-Winter Harbor, predicted that his caucus would be skeptical about such a bill. But Faulkingham said he looked forward to reviewing it to see if it was “sensible and compassionate” and affordable. It’s unclear how much the expansion would cost. Last session, Talbot Ross estimated that it would cost nearly $8 million, a sum that also included expansions that ended up being in the governor’s budget. Forty states have federal options to cover lawfully residing children or pregnant women, or provide prenatal care regardless of immigration status, or use state funds to cover certain immigrants, according to the National Immigration Law Center. But it’s unclear how many states cover all noncitizens who would otherwise qualify for Medicaid. Maine provided public health benefits to noncitizens up until 2011, when former Republican Gov. Paul LePage successfully eliminated their eligibility. Kathy Kilrain del Rio, advocacy and program director for Maine Equal Justice, which is part of a coalition advocating for the legislation, said the bill would essentially restore those benefits that were eliminated under LePage, giving noncitizens access to preventive health services, such as regular doctor’s visits and medication. PROMOTING PREVENTIVE CARE Under the current system, noncitizens often allow their conditions to deteriorate to the point where they either go to the emergency room for care, or die, Kilrain del Rio said. That can leave serious health problems, like cancer or diabetes, undiagnosed, she said. “It’s better to have people have access to preventive care so that conditions can be caught early and treated often in relatively simple ways rather than have them escalate to the point where people have to go to emergency rooms,” she said. “That’s a much more expensive way to treat problems.” Mufalo Chitam, executive director of the Maine Immigrant’s Rights Coalition, said the bill is needed now more than ever, because of the growing number of asylum seekers who are coming to Maine. For most of last year, Chitam said her organization helped organize health clinics twice a week for asylum seekers staying at the Howard Johnson in South Portland. Those clinics highlighted not only the need for preventive care, with people suffering from the effects of untreated diabetes, eye and ear problems, bone fractures, infections and other injuries sustained on their long journey to the U.S., but also follow-up care, she said. In one case, Chitam said, a mother of two teenage children was diagnosed with cancer and died. “By the time she was being seen as an emergency it was way too late,” Chitam said. “It’s really a matter of life and death.” BILLS TO TIGHTEN ELIGIBILITY Sen. Eric Brakey, R-Auburn, has submitted several bills that would tighten welfare eligibility. He said the U.S. cannot have “open borders and (a) welfare state.” “I think a lot of Maine taxpayers want to make sure the social safety net is going to folks who paid into the system,” Brakey said. Rep. Deqa Dhalac, D-South Portland, is one of the bill’s eight co-sponsors. She said health coverage would relieve the burden on asylum seekers and other noncitizens as they pursue their asylum claims and gain access to work permits, so they can contribute to society. Even noncitizens who do work – such as in home health care or hotels and restaurants – are not always guaranteed access to health care. “As a social worker, I think it’s our responsibility as human beings in general to take care of our communities, our neighbors, and these are some of the people that are really doing a lot of work,” she said. “They don’t want handouts. They want to work. They want to contribute to the economy or just the country as well as the state, and we’re just providing a small stipend for their health and well being.”

Top challenges of 2022, No. 5: Loss of trust in physicians by Medical Economics Staff

Editor's Note: The past year has been one of the most challenging on record for U.S. physicians. After the lockdowns and telehealth surge of 2020, the year 2021 has been strange. Although things went back to “normal” in that most practices resumed seeing patients in person, the COVID-19 pandemic and its challenges remain. As we do each year, Medical Economics® surveyed our audience to find out what the big challenges were. By far, the top answer was “administrative burdens” including staffing, prior authorizations and electronic health records (EHRs). We decided to take a closer look at what these burdens entail, to help physicians get ready for whatever challenges 2022 will bring. Here's number five. Doctors often complain that, like the late comedian Rodney Dangerfield, they “don’t get no respect.” But when it comes to respect and trust, medicine and its practitioners fare better than many other aspects of American society. In a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 74% of respondents said they had a “mostly positive” view of medical doctors. By contrast, only 35% said they had a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence that elected officials will act in the public’s best interest, and 46% said the same of business leaders. Still, trust in physicians has been declining. In a 2017 Sermo survey, 87% of doctors said patients trust them less than they did a decade earlier. The trend is especially pronounced among younger Americans. A November 2021 Morning Consult survey found that 74% of baby boomers trust the health care system “some” or “a lot,” but that number drops to 44% among members of Generation Z — those born between the late 1990s and early 2010s. What has caused this erosion of trust in doctors, and medicine generally? In part, experts say, it reflects Americans’ ongoing loss of faith in all institutions that began with the Vietnam War and Watergate. But there are also reasons specific to medicine. Probably the biggest of these is the limited time primary care doctors working for large hospital systems — now the majority — can spend with patients. Bioethicist Stephen Post, Ph.D., told Medical Economics® in 2018 that many hospital systems, where the majority of primary care physicians now practice, require doctors to see an average of eight patients in 30 minutes. “Given that pace, it’s extremely difficult to build trust and create meaningful relationships,” Post said. Compounding the problem, patients often do not stay with the same doctor long enough to establish trust; doctors leave (or are dropped from) insurance networks, or employers change insurance carriers in search of lower costs. Another contributor to eroding trust is the ready availability of medical and wellness information, as well as information and ratings for health care providers, on the internet and via social media. A 2015 Medical Economics® article noted that about 5% of all Google searches were health-related and the percentage has almost certainly grown since then. “We’ve seen an explosion in the kind of information that ordinary people can access about their own health and from sources like medical journals and the results of clinical trials,” author and patient engagement consultant Jan Oldenburg told Medical Economics® in 2019. Oldenburg and other experts say that although this “patient empowerment” lets patients become more actively involved in their health and wellness, it also means they are less likely to unquestioningly trust a physician’s diagnosis or follow a treatment plan than were patients in the era before the internet. Patients’ confidence in their care providers is further weakened by skyrocketing care costs. Although doctors are not primarily responsible for the problem, they often bear the brunt of patient anger. Eighty-seven percent of physician respondents to a 2016 Medical Economics® survey said their practices were encountering more angry patients than a year or two earlier, and 56% said financial issues were the main cause of patient anger. Among some patients, that anger takes the form of believing their doctor is recommending unnecessary tests or procedures to earn more money. Of course, for large groups within American society — especially people of color — mistrust of doctors and the health care system is longstanding and frequently justified. A 2003 Institute of Medicine report on racial and ethnic disparities in health care found evidence that “stereotyping, biases and uncertainty on the part of health care providers can all contribute to unequal treatment.” Moreover, the report said, White clinicians who do not believe they are prejudiced “typically demonstrate unconscious implicit negative racial attitudes and stereotypes.” Many public health experts believe this distrust among members of the Black and Hispanic communities contributed to their initial reluctance to get COVID-19 vaccines as compared with White people (although the gap has since narrowed). Establishing — or rebuilding — trust with patients is not easy, especially given the time and financial constraints most doctors face. Nevertheless, it is possible. The process starts with maximizing the time available to spend with patients by, for example, delegating to staff members tasks that reduce time for doctor-patient interactions. Then use the time to listen. “Let patients talk about the personal aspects of their illness, then add an affirming comment like ‘That must be very difficult,’” Post advises. Dhruv Khullar, M.D., M.P.P., a New York City internist and author of a New York Times article about trust, reminds doctors that they can no longer expect trust automatically, but “if we work hard to demonstrate that we’re trustworthy, patients will come to trust us over time.”

Emailing Your Doctor May Carry a FeeMore hospitals and medical practices have begun charging for doctors’ responses to patient queries, depending on the level of medical advice. by Benjamin Ryan _ NYT - January 24, 2023 To Nina McCollum, Cleveland Clinic’s decision to begin billing for some email correspondence between patients and doctors “was a slap in the face.” She has relied on electronic communications to help care for her ailing 80-year-old mother, Penny Cooke, who is in need of specialized psychiatric treatment from the clinic. “Every 15 or 20 dollars matters, because her money is running out,” she said. Electronic health communications and telemedicine have exploded in recent years, fueled by the coronavirus pandemic and relaxed federal rules on billing for these types of care. In turn, a growing number of health care organizations, including some of the nation’s major hospital systems like Cleveland Clinic, doctors’ practices and other groups, have begun charging fees for some responses to more time-intensive patient queries via secure electronic portals like MyChart. Cleveland Clinic said that its email volume had doubled since 2019. But it added that since the billing program began in November, fees had been charged for responses to less than 1 percent of the roughly 110,000 emails a week its providers received. “Billing a patient’s health insurance supports the necessary decision-making and time commitment of our physicians and other advanced professional providers,” said Angela Smith, a spokeswoman for the clinic. But a new study shows that the fees, which some institutions say range from a co-payment of as little as $3 to a charge of $35 to $100, may be discouraging at least a small percentage of patients from getting medical advice via email. Some doctors say they are caught in the middle of the debate over the fees, and others raised concerns about the effects that the charges might have on health equity and access to care. Dr. Eve Rittenberg, an internist in women’s health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, examined the effects of medical correspondence with patients in a study that found that female practitioners shouldered a greater communications burden. “The volume of messaging combined with the expectation of quick turnaround is very stressful,” Dr. Rittenberg said. She recalled one day when she took her teenage daughter to the doctor but was distracted by responding to patient messages on her phone. She recently reduced her clinic schedule — and took a commensurate pay cut — to free up a few hours outside of office visits to cope with other tasks like patient messages. The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services first introduced Medicare billing codes in 2019 that allowed providers to seek reimbursement for writing messages through secure portals. The pandemic prompted the agency to broaden coverage for telemedicine and hospitals significantly expanded its overall use. The federal rules state that a billable message must be in response to a patient inquiry and require at least five minutes of time, effectively making it a virtual visit. Private insurers have widely followed Medicare’s lead, reimbursing health care practices for physicians’ emails, and may charge patients a co-pay. For several major hospital systems across the country, the increase in email fees has opened up a new revenue stream. Blue Cross Blue Shield said some of its state and regional plans reimburse for doctor emails. But David Merritt, a senior vice president for policy and advocacy for the insurer, expressed concern that the ability “to charge patients for what often should be routine email follow-up could easily be viewed and abused as a new revenue stream.” According to the Cleveland Clinic, Medicaid patients are not charged. Medicare beneficiaries without a supplemental health plan would owe a co-pay between $3 and $8. The clinic’s maximum charge, hitting those with high deductibles on private insurance plans or without coverage, would be $33 to $50 for each exchange. Ms. McCollum and other clinic patients are given the option of avoiding such fees by choosing to discontinue a query or request an appointment instead. Ms. McCollum kept on emailing on behalf of her mother: “I said, ‘Yes,’ because I need to reach her doctor.” She added, “It’s maddening.” Not all patient-doctor exchanges carry fees. Emails for simpler concerns largely remain free, including for prescription refills, appointment scheduling and follow-up care. According to several hospital systems and insurers, electronic communications that could prompt a bill would address, for example, medication changes, a new medical issue or symptom or shifts in long-term health conditions. Providers may only bill a patient once a week. Nearly a dozen of the nation’s largest hospital systems said they charged fees for some of their providers’ emails to patients or have started pilot programs, in response to an informal survey by The New York Times. In addition to Cleveland Clinic, this includes Houston Methodist; NorthShore University HealthSystem, Lurie Children’s, and Northwestern Medicine in Illinois; Ohio State University; Lehigh Valley Health Network in Pennsylvania; Oregon Health & Science University; University of California, San Francisco and U.C. San Diego; and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Other major hospitals are closely watching those at the vanguard of this new billing practice, according to A Jay Holmgren, an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at U.C.S.F. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) permits doctors to send unencrypted emails or texts if they caution patients about the risks of unsecure channels. But to protect patient privacy, prevent hacking and comply with other HIPAA requirements, most health care companies and organizations discourage the use of anything other than the encrypted portals like MyChart that have become ubiquitous over the past decade. Hospital officials note that while young people may be the most tech-savvy and wedded to app-based correspondence, they are usually healthier and less apt to keep in touch with their doctors. “In my own experience, most messages come from individuals in their 50s and 60s, likely because they are sufficiently familiar with technology to learn how to use messaging and are starting to have increasing needs, whether screening or illness-related,” said Dr. Daniel R. Murphy, an internist and chief quality officer at Baylor Medicine in Houston, which does not currently bill for emails. Before the pandemic, Dr. Murphy found in his research that primary care doctors spent about an hour a day managing their inbox. But a recent study led by Dr. Holmgren of data from Epic, a dominant electronic health records company, showed that the rate of patient emails to providers had increased by more than 50 percent in the last three years. “We’re at an inflection point with messaging,” Dr. Holmgren said. “How are we going to deliver care in the future as we continuously move away from all care being a discrete visit?” Many doctors and their assistants have little time during work hours for replying to patients. Doctors find themselves attending to such demands during “pajama time” before bed, according to Dr. Anthony Cheng, an associate professor of family medicine at Oregon Health & Science. “We know that this is a contributor to burnout,” Dr. Rittenberg said. “Burnout and resulting attrition in physicians’ work is becoming a crisis in our medical system.” Dr. Rittenberg teamed up with her husband, Jeffrey B. Liebman, an economist at the Harvard Kennedy School, to study electronic health record responsibilities among primary care doctors at Brigham. In an article published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in January 2022, they reported that female doctors spent more time responding to messages and received more messages from both patients and staff members than their male colleagues. This difference, they surmised, could help explain greater burnout rates among women in medicine. Some doctors have reported examples of patients who communicate too frequently or insistently through the online portal. “People now have the expectation that these communications are like texts and that they should get a response right away,” Dr. Rittenberg said. But, she said she empathized with what might be driving such patients’ insistent inquiries: pandemic-era malaise. “People are very anxious and worried and isolated, and the doctor offers a connection,” she said. Attaching a monetary fee to doctor-patient emails may be a step toward recognition of the value of this particular practice. But the addition of another bill has primed simmering resentments among some Americans, who are experiencing “pandemic fatigue” and have strained household budgets because of inflation, including higher health care costs. Ms. McCollum, a marketing writer, has been trying to raise extra cash to help cover her mother’s care by selling some of Ms. Cooke’s belongings online. “It’s been a tough year and I don’t need the clinic making it any worse,” she added. Dr. Kedar Mate, chief executive at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, a nonprofit in Boston, said charging for providers’ emails amounted to “a very complicated and slippery slope” and that it could exacerbate health inequities. “Increasing levels of communication and interactions with patients is a good thing,” Dr. Mate said. “And I worry about disincentivizing that by creating a financial barrier.” Caitlin Donovan, senior director of the Patient Advocate Foundation, said that even a small co-pay could prove alienating to people living paycheck to paycheck. “We write a lot of $5 checks in this organization,” she said, referring to subsidies for co-pays and other out-of-pocket medical expenses. Others pointed out that when a severe physician shortage left patients waiting months to see a specialist, exchanging messages was a time-efficient way to bridge those gaps. “It’s really been a win-win for our physicians and our patients,” said LeTesha Montgomery, senior vice president for system patient access at Houston Methodist, which rolled out a full billing plan beginning in September. “So, it actually helped us increase access for our patients,” she said. Some patients view billing for a provider’s time and expertise as only fair and a good use of their own time, as well. Kacie Lewis, 29, is among those who manage their health concerns electronically. Until recently, her Aetna insurance coverage had a high deductible, through her work as a product manager at a health care company. And since late 2021, she said, she had been billed $32 for each of three email threads, seeking treatments for psoriasis, eczema and a yeast infection from providers at Novant Health in Charlotte, N.C. “Time is money,” Ms. Lewis said. “And to be able to submit something super simple and communicate with your doctor over email is much better than driving 20 minutes one way, 20 minutes back the other way and potentially sitting in the waiting room.” In a paper published on Jan. 6 in JAMA, Dr. Holmgren and his colleagues reported that after U.C.S.F. Health started its email billing in November 2021, there was a slight drop in the number of patient emails to providers. The researchers suggested that might have been the result of patients’ reluctance to be charged a fee. In the first year, U.C.S.F. billed for 13,000 message threads, or about 1.5 percent of 900,000 threads and more than three million messages, according to the study. (Other hospitals told The Times they billed for no greater than 2 percent of threads.) From about $20 from Medicare and Medicaid and $75 from commercial insurers per bill, the email fees generated $470,000, compared with the system’s $5.6 billion in 2021 revenues. “This will hopefully be revenue-neutral,” Dr. Holmgren said. “We are not intending to make this a profitable enterprise.” Critics argue that billing for a small fraction of emails is not likely to reduce physician burnout substantially unless hospitals also set aside workday hours for patient queries and reward clinicians for those efforts. U.C.S.F. has begun giving “productivity points,” a metric used for compensation, for doctors’ correspondence. Jack Resneck Jr., president of the American Medical Association, said he supported insurance coverage for emailing as a way to adjust health care models to fast-changing times. “How do we reinvent the physician’s day and the care delivery system to actually recognize and support the broad array of ways that we deliver care?” Dr. Resneck asked. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/24/health/emails-billing-doctors-patients.html

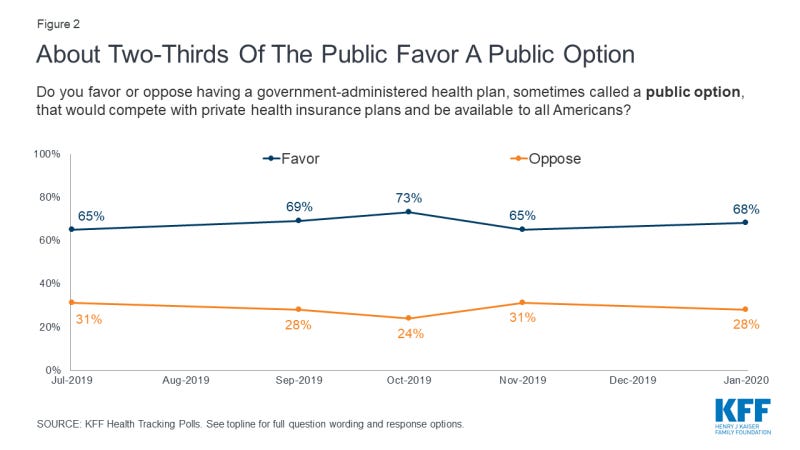

Democrats are from .gov, Republicans are from .com: Prognosis for a public option open to all in U.S. healthcareA team of researchers led by Adrianna McIntyre finds deep ideological fissures beneath apparent broad support for a public optionby Andrew Sprung - NYT - January 28, 2023In polling about U.S. healthcare, the prospect of a “public option” for health insurance, open to all Americans regardless of whether they have access to employer-sponsored insurance, generally scores high. Here is the top-line response to a Kaiser Family Foundation tracking poll conducted in January 2020: Looking beneath the hood of that apparent relative consensus, a research team led by Adrianna McIntyre of Harvard’s Chan School of Public Health conducted a poll in November/December 2020 that probed attitudes toward government that underlie responses to health reforms including a public option — specifically, a Medicare buy-in for people under age 65. The researchers published an analysis* in Milbank Quarterly this month. While top-line results were similar to KFF’s, the researchers note:

These divisions make the authors skeptical as to the prospects of establishing a public option, especially given the powerful industry interests that view the public option as a threat either to their existence in current form (insurers) or to the commercial payer gravy train (providers). They posit that consolidation within the healthcare industry in recent years “may actually make industry actors more formidable foes to health reforms that they view as detrimental to their interests than they had been in 2009.” McIntyre et al. suggest that the political divide underlying apparent strong top-line support makes it unlikely that a reform of this kind can pass with bipartisan support, which until the Obama years was widely considered essential for transformative legislation. On the other hand, citing Democrats’ 2022 passage on a party-line vote (with a razor-thin majority) of legislation empowering Medicare to negotiate select drug prices, the authors allow that a broadly available public option might ultimately become law on a similar basis. This paper’s exposure of “wide partisan attitude gaps…under a surface of broad support” is illuminating. In a way, though, it seems to me that a public option open on an affordable basis to all who want or need is at least conceptually aligned with a political reality in which, with respect to a public option,

With a very large caveat, it’s possible to read the history and current state of Medicare as evidence that a hybrid system can (and does) exist that offers some satisfaction to both the Democratic and Republican propensities outlined above. Medicare provides one benefit of “public” ownership that all enrollees — and all taxpayers— benefit from: effective government control over provider payment rates (albeit with arguably excessive provider input). For those who choose traditional, fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare (e.g., those who can afford or have access to employer-subsidized Medigap), “public” FFS Medicare offers two other powerful benefits: near-unlimited choice of providers, and freedom from the sometimes onerous restrictions of managed care (prior authorization requirements and more frequent coverage denials or limitations, e.g. in post-acute care in particular). On the Republican side of the equation, our national infatuation with markets has led to an almost insane proliferation of choice among private options — e.g., of an average of 39 Medicare Advantage plans, or, on the “public option” side, a similarly baffling array of Part D prescription drug plans and Medigap plans, which are all private. The caveat: policy choices have tilted the field so heavily toward Medicare Advantage that the equipoise outlined above is an endangered species. Those policy choices include failing to plug major holes in FFS Medicare coverage — chiefly the lack of a cap on out-of-pocket expenses — and payment formulas generous enough to MA plans to enable them to offer almost irresistible advantages to non-affluent enrollees who lack subsidized access to Medigap or who are not low-income and asset-poor enough to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. More than 60% of MA plan enrollees pay no more than the statutory Part B premium for coverage that includes a cap on out-of-pocket costs, a Part D plan, and ancillary services. That means their premiums are typically less than half of the combined premiums of Medicare Parts B and D plus Medigap. MA plans also offer ancillary services, usually including at least limited dental, vision and hearing coverage, that MedPAC values at $2,000 per enrollee per year. Those lower up-front costs and extra benefits are offered in exchange for higher out-of-pocket costs (compared to FFS + Medigap), limits (large or small) on choice of providers, and exposure to prior authorization and more frequent coverage denials. As MA offers a deal that a rapidly growing share of enrollees feel they can’t afford to refuse, its market share has grown by leaps and bounds in recent years and now stands just below half of all enrollees. If current trends continue, FFS Medicare may lose its capacity to serve as a benchmark for federal payments to MA plans, which would untether the rates MA plans pay providers from Medicare rates set by CMS. As McIntyre et al. point out,

That said, the equipoise that has existed for 20 years between MA and FFS Medicare is at least imaginable for the healthcare system as a whole — and has been imagined in a number of proposals and bills. Early iterations of such a "public option" include Helen Halpin's CHOICE program (2003), Rep Peter Stark's Americare bill (2006),and Jacob Hacker's Health Care for America plan (2007). All of these enabled any individual to buy in on an income-adjusted basis regardless of whether her employer offered insurance, and gave employers the option of paying into the public plan (e.g., via a payroll tax) rather than offering their own plans. While Halpin’s plan was actually titled "Getting to a Single-Payer System Using Market Forces," Hacker’s (introduced as Democrats inched toward power) envisioned fruitful competition between ESI and the expanded Medicare program: A Lewin Group analysis of Hacker’s plan forecast that half of the nonelderly population would remain in employer-sponsored plans. More recently, the Medicare for America bill introduced by Reps Rosa DeLauro (CT-03) and Jan Schakowsky (IL-09) offers a revamped “Medicare” to all who want it — and implicitly preserves the employer market by mandating that providers accept a revamped Medicare payment schedule from commercial payers. My point is that these plans reflect and attempt to accommodate the partisan ideological fissure that McIntyre et al. present as a potentially disabling condition. That’s not to say that McIntyre et al. are wrong. In fact, the prospects for anything like Medicare for America look very distant — endangered by the evolution of Medicare as well as by the fierce industry opposition recounted by McIntyre et al. To illustrate the latter, they cite the American Hospital Association’s attack on the public option in Senator Michael Bennet’s Medicare-X plan, which ring-fenced the public option within the ACA marketplace, making it available on a subsidized basis only to those who lacked access to employer-sponsored insurance. While the Medicare-X public option would be available to only a small sliver of the population — subsidized ACA marketplace enrollment totaled less than 10 million at the time the bill was introduced — providers regarded it as a camel’s nose in the tent (and the bill did provide for an opening to the small group market within a few years). In fact it might be argued that our governments, federal and state, are losing the capacity and will to manage healthcare financing and delivery. That is, the increasing dominance of commercially-managed plans in Medicare and Medicaid, as McIntyre et al. imply, may be foreclosing on a true hybrid system. Perhaps our inability to implement rate-setting in FFS Medicare strong enough to fund less gap-ridden coverage creates irresistible pressure to impose managed care that squeezes high-value as well as low-value treatment. The ACO Reach program, which seeks replace the relatively passive claims management of the Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) with more actively managed care, indicates as much. Maybe, too, the lobbying clout of providers, insurers and pharma will effectively decide between Democratic and Republican ideological preferences, in favor of Republican. On the other hand… there is the minor miracle of the prescription drug price negotiation (for a limited set of drugs) and inflation caps on drug prices included in the Inflation Reduction Act last summer. McIntyre et al. point to key differences between passage of this reform and the prospects for a public option: The drug price controls reduce spending rather than increasing it; they benefit all seniors, not just the poor (for which many voters read ‘minority’); and its polling support “seems substantially less malleable” than the public option’s. Conversely, though, perhaps the drug price negotiation enacted in the IRA is a model for future reform, in that it both depends on government pricing power and applies that power in a commercially run market. Democrats also came within a whisker of applying the inflation caps in the commercial market. Government-imposed price control is perhaps the deepest underlying rationale for a public option — and the savings rate-setting would yield might share the “less malleable” support the public grants to drug price control. In sum, the balance and tension between government and market control of healthcare in the U.S. mirrors — or is rather perhaps the largest instance of — the balance and tension between government authority and market forces in our society as a whole. By “balance,” I don’t mean to suggest “optimal balance.” In my view, the U.S. system has let market forces in healthcare — and the behemoths we’ve allowed those forces to breed — run out of control. A warning from a former health minister of Singapore, relayed in William Haseltine’s Affordable Excellence: The Singapore Health System (Brookings, 2013, free on Kindle) has stayed with me as a durable guiding principle:

We are faced with that very difficult unwinding, as McIntyre et al. hammer home. Postscript: One point at which the gravitational pull favoring the private market prevailed was in the ACA’s conception. McIntyre et al. recount how the public option included in the House bill was stripped out by conservative Democratic senators. Somewhat elided in their narrative is the question of why, by the time the ACA was drafted, the target population for what became the ACA marketplace was limited to those who lack access to affordable employer-sponsored insurance or other coverage. By 2009, what had happened to the broad “Medicare for all who want it” type plans described above, and introduced between 2003 and 2007? Short answer, as narrated in Jonathan Cohn’s The Ten Year War: Obamacare and the Unfinished Crusade for Universal Coverage: Massachusetts health reform, enacted in 2006 by Mitt Romney and the MA legislature, happened. The Massachusetts prototype, combining expanded Medicaid access and a marketplace of subsidized private plans for those who earned too much to qualify for Medicaid, provided proof-of-concept for a more limited initiative that could credibly cover most of the uninsured. And as Cohn recounts, at that point Congressional Democrats believed that they could win Republican buy-in to a scheme that relied in large part on the private market. None of the three major Democratic presidential candidates in 2007-2008 presented a health reform plan that seriously disrupted the employer-sponsored market or offered anything like “Medicare for all who want it.” —— * Adrianna McIntyre, Robert J. Blendon, John M. Benson, Mary G. Findling, Eric C. Schneider, “Popular… to a Point: The Enduring Political Challenges of the Public Option.” Milbank Quarterly, Vol OO, No. O, 2023 (pp 1-23). As ACA enrollment reaches record highs nationwide, Maine sees decline for 2023By Patty Wight - Maine Public - January 27, 2023The Affordable Care Act marketplace saw a record number of signups nationwide for 2023, but Maine saw a decrease in enrollment. Roughly 63,000 Mainers signed up for health insurance on the marketplace, compared with 66,000 last year. Ann Woloson, executive director of Consumers for Affordable Health Care, says one likely reason for the decline is the improved economy. "People are getting jobs that are providing them with health insurance so they haven't had to rely on the marketplace," she says. Another reason, Woloson says, is that people on MaineCare have received continuous eligibility throughout the pandemic. But that will end in April, and she says some people may transition to the marketplace under a special enrollment period. According to Maine's Department of Health and Human Services, 83% of consumers who enrolled in 2023 marketplace plans received financial assistance, and more than 10,000 are paying monthly premiums that are under $10. How a Drug Company Made $114 Billion by Gaming the U.S. Patent SystemAbbVie for years delayed competition for its blockbuster drug Humira, at the expense of patients and taxpayers. The monopoly is about to end. by Rebecca Robbins - NYT - January 28, 2023 In 2016, a blockbuster drug called Humira was poised to become a lot less valuable. The key patent on the best-selling anti-inflammatory medication, used to treat conditions like arthritis, was expiring at the end of the year. Regulators had blessed a rival version of the drug, and more copycats were close behind. The onset of competition seemed likely to push down the medication’s $50,000-a-year list price. Instead, the opposite happened. Through its savvy but legal exploitation of the U.S. patent system, Humira’s manufacturer, AbbVie, blocked competitors from entering the market. For the next six years, the drug’s price kept rising. Today, Humira is the most lucrative franchise in pharmaceutical history. Next week, the curtain is expected to come down on a monopoly that has generated $114 billion in revenue for AbbVie just since the end of 2016. The knockoff drug that regulators authorized more than six years ago, Amgen’s Amjevita, will come to market in the United States, and as many as nine more Humira competitors will follow this year from pharmaceutical giants including Pfizer. Prices are likely to tumble. The reason that it has taken so long to get to this point is a case study in how drug companies artificially prop up prices on their best-selling drugs. AbbVie orchestrated the delay by building a formidable wall of intellectual property protection and suing would-be competitors before settling with them to delay their product launches until this year. The strategy has been a gold mine for AbbVie, at the expense of patients and taxpayers. Over the past 20 years, AbbVie and its former parent company increased Humira’s price about 30 times, most recently by 8 percent this month. Since the end of 2016, the drug’s list price has gone up 60 percent to over $80,000 a year, according to SSR Health, a research firm. One analysis found that Medicare, which in 2020 covered the cost of Humira for 42,000 patients, spent $2.2 billion more on the drug from 2016 to 2019 than it would have if competitors had been allowed to start selling their drugs promptly. In interviews, patients said they either had to forgo treatment or were planning to delay their retirement in the face of enormous out-of-pocket costs for Humira. AbbVie did not invent these patent-prolonging strategies; companies like Bristol Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca have deployed similar tactics to maximize profits on drugs for the treatment of cancer, anxiety and heartburn. But AbbVie’s success with Humira stands out even in an industry adept at manipulating the U.S. intellectual-property regime. “Humira is the poster child for many of the biggest concerns with the pharmaceutical industry,” said Rachel Sachs, a drug pricing expert at Washington University in St. Louis. “AbbVie and Humira showed other companies what it was possible to do.” Following AbbVie’s footsteps, Amgen has piled up patents for its anti-inflammatory drug Enbrel, delaying a copycat version by an expected 13 years after it won regulatory approval. Merck and its partners have sought 180 patents, by one count, related to its blockbuster cancer drug Keytruda, and the company is working on a new formulation that could extend its monopoly further. Humira has earned $208 billion globally since it was first approved in 2002 to ease the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. It has since been authorized to treat more autoimmune conditions, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Patients administer it themselves, typically every week or two, injecting it with a pen or syringe. In 2021, sales of Humira accounted for more than a third of AbbVie’s total revenue. An AbbVie spokesman declined to comment. The company’s lawyers have previously said it is acting within the parameters of the U.S. patent system. Federal courts have upheld the legality of AbbVie’s patent strategy with Humira, though lawmakers and regulators over the years have proposed changes to the U.S. patent system to discourage such tactics. In 2010, the Affordable Care Act created a pathway for the approval of so-called biosimilars, which are competitors to complex biologic drugs like Humira that are made inside living cells. Unlike generic equivalents of traditional synthetic medications, biosimilars usually are not identical to their branded counterparts and cannot be swapped out by a pharmacist. The hope was that biosimilars would drastically drive down the cost of pricey brand-name biologics. That is what has happened in Europe. But it has not worked out that way in the United States. Patents are good for 20 years after an application is filed. Because they protect patent holders’ right to profit off their inventions, they are supposed to incentivize the expensive risk-taking that sometimes yields breakthrough innovations. But drug companies have turned patents into weapons to thwart competition. AbbVie and its affiliates have applied for 311 patents, of which 165 have been granted, related to Humira, according to the Initiative for Medicines, Access and Knowledge, which tracks drug patents. A vast majority were filed after Humira was on the market. Some of Humira’s patents covered innovations that benefited patients, like a formulation of the drug that reduced the pain from injections. But many of them simply elaborated on previous patents. For example, an early Humira patent, which expired in 2016, claimed that the drug could treat a condition known as ankylosing spondylitis, a type of arthritis that causes inflammation in the joints, among other diseases. In 2014, AbbVie applied for another patent for a method of treating ankylosing spondylitis with a specific dosing of 40 milligrams of Humira. The application was approved, adding 11 years of patent protection beyond 2016. The patent strategy for Humira was designed to “make it more difficult for a biosimilar to follow behind,” Bill Chase, an AbbVie executive, said at a conference in 2014. AbbVie has been aggressive about suing rivals that have tried to introduce biosimilar versions of Humira. In 2016, with Amgen’s copycat product on the verge of winning regulatory approval, AbbVie sued Amgen, alleging that it was violating 10 of its patents. Amgen argued that most of AbbVie’s patents were invalid, but the two sides reached a settlement in which Amgen agreed not to begin selling its drug until 2023. Over the next five years, AbbVie reached similar settlements with nine other manufacturersseeking to launch their own versions of Humira. All of them agreed to delay their market entry until 2023. Sue Lee, 80, of Crestwood, Ky., had been taking Humira for years to prevent painful sores caused by a chronic skin condition known as psoriasis. Her employer’s insurance plan had helped keep her annual payments to $60. Then she retired. Under Medicare rules, she would have to pay about $8,000 a year, which she could not afford. “I cried a long time,” she said. For months, Ms. Lee stopped taking any medication. The sores “came back with a vengeance,” she said. She joined a clinical trial to temporarily get access to another medication. Now she is relying on free samples of another drug provided by her doctor. She doesn’t know what she’ll do if that supply runs out. Barb Teron, a book buyer in Brook Park, Ohio, plans to delay her retirement because she is worried about Humira’s cost. Ms. Teron, who takes Humira for Crohn’s disease and colitis, has never had to pay more than $5 for a refill of the drug because her employer’s insurance plan picks up most of the tab. The cost, according to a pharmacy app on Ms. Teron’s phone, was $88,766 in the past year. Ms. Teron, who turns 64 in March, would have liked to retire next year, but that would have meant relying on Medicare. She fears that her out-of-pocket costs will spiral higher. “When I look at that $88,000 charge for a year, there’s no way,” Ms. Teron said. AbbVie executives have acknowledged that Medicare patients often pay much more than privately insured people, but they said the blame lay with Medicare. In 2021 testimony to a congressional committee investigating drug prices, AbbVie’s chief executive, Richard Gonzalez, said the average Medicare patient had to pay $5,800 out of pocket annually. (AbbVie declined to provide updated figures.) He said AbbVie provided the drug for virtually nothing to nearly 40 percent of Medicare patients. The drug’s high price is also taxing employers. Soon after she started taking Humira, Melissa Andersen, an occupational therapist from Camdenton, Mo., got a call from a human resources representative at her company. The company directly covers its employees’ health claims, rather than paying premiums to an insurer. Her Humira was costing the company well over $70,000 a year — more than Ms. Andersen’s salary. The H.R. employee asked if Ms. Andersen would be willing to obtain the drug in an unconventional way to save money. She said yes. As soon as March, her company plans to fly Ms. Andersen, 48, to the Bahamas, so that a doctor can prescribe her a four-month supply of Humira that she can pick up at a pharmacy there. Humira is much cheaper in the Bahamas, where the industry has less influence than in it does in Washington and the government proactively controls drug pricing. It is not yet clear how much the knockoff products will cost and how quickly patients will switch over to them. Billions of dollars in drug spending will ride on the answers to those questions. “We price our products according to the value they deliver,” said Jessica Akopyan, a spokeswoman for Amgen, whose biosimilar product comes to market on Tuesday. She added that the company would “employ flexible pricing approaches to ensure patient access.” Even now, as AbbVie prepares for competitors to erode its Humira sales in the United States, the company will have a new way to make more money from the drug. Under the terms of the legal settlements it reached with rival manufacturers from 2017 to 2022, AbbVie will earn royalties from the knockoff products that it delayed. The exact sizes of the royalties are confidential, but analysts have estimated that they could be 10 percent of net sales. That could translate to tens of millions of dollars annually for AbbVie. In the longer run, though, AbbVie’s success with Humira may boomerang on the drug industry. Last year, the company’s tactics became a rallying cry for federal lawmakers as they successfully pushed for Medicare to have greater control over the price of widely used drugs that, like Humira, have been on the market for many years but still lack competition. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/28/business/humira-abbvie-monopoly.html

|