Democrats Propose Raising Taxes on Some High Earners to Bolster Medicare

The draft plan, which is expected to be unveiled in the coming days, is part of talks over how to salvage pieces of President Biden’s domestic agenda.by Emily Cochrane, Margot Sanger-Katz and Jim Tankersley - NYT - July 7, 2022

WASHINGTON — Senate Democrats will push to raise taxes on some high-earning Americans and steer the money to improving the solvency of Medicare, according to officials briefed on the plan, as they cobble together a modest version of President Biden’s stalled tax and spending package.

The proposal is projected to raise $203 billion over a decade by imposing an additional 3.8 percent tax on income earned from owning a piece of what is known as a pass-through business, such as a law firm or medical practice. The money that would be generated by the change is estimated to be enough to extend the solvency of the Medicare trust fund that pays for hospital care — currently set to begin running out of money in 2028 — until 2031.

It is the most recent agreement to emerge from private negotiations between Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the majority leader, and Senator Joe Manchin III of West Virginia, a conservative-leaning Democrat who has demanded that his party rein in its sweeping ambitions for a domestic policy plan. In December, Mr. Manchin torpedoed efforts to pass Mr. Biden’s $2.2 trillion social safety net, climate and tax package because of concerns over its cost and impact on the economy at a time of rising inflation.

His backing is critical because, with Republicans expected to be uniformly opposed, the only way Democrats can pass the package through the evenly divided Senate is to win unanimous backing from their caucus and do so under special budget rules that would shield it from a filibuster and allow it to pass on a simple majority vote.

Mr. Schumer has worked to salvage key components of the plan that could meet that test, including a plan released on Wednesday to lower the cost of prescription drugs. Mr. Manchin has repeatedly said such legislation should focus on tax reform and drug pricing, as well as efforts to lower the national debt. The bill is also expected to include some climate and energy provisions, a key priority for Democrats, although they have yet to be agreed upon.

Democratic leaders, who hope to move the legislation through the Senate this month, are expected to formally release the Medicare plan in the coming days, according to the officials, who disclosed preliminary details on the condition of anonymity.

The fast-track budget process that the party plans to use for the overall package, known as reconciliation, requires legislation to abide by strict budgetary rules enforced by the Senate parliamentarian. The prescription drug legislation has been submitted to the parliamentarian, and Democrats plan to submit the tax increase and Medicare piece in coming days.

The portion of Medicare that pays for hospital bills is funded through a special trust fund, largely financed by payroll taxes. But with escalating health care costs and an aging population, current revenues won’t be enough to pay all of Medicare’s hospital bills forever. According to the most recent report from Medicare’s trustees, the fund will be depleted in 2028 without new revenues or spending cuts.

The Democrats’ plan would extend an existing 3.8 percent net investment income tax to so-called pass-through income, earned from businesses that distribute profits to their owners. Many people who work at such firms — such as law partners and hedge fund managers — earn high incomes, but avoid the 3.8 percent tax on the bulk of it.

The new proposal would apply only to people earning more than $400,000 a year, and joint filers, trusts and estates bringing in more than $500,000, in accordance with Mr. Biden’s pledge that he would not raise taxes for people who make less than $400,000 a year. The proposal is similar to a tax increase Mr. Biden proposed in 2021 to help offset the cost of a set of new spending programs meant to help workers and families, like home health care and child care.

Imposing the new tax on pass-through income would raise about $202.6 billion over a decade, according to an estimate from the Joint Committee on Taxation provided to Senate Democrats and reviewed by The New York Times. Those funds would be funneled directly into the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which covers inpatient hospital care, some home health care and hospice care.

The Office of the Actuary in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services informed Democratic staff that the additional revenue generated would extend the hospital trust fund’s solvency from 2028 to 2031.

“Medicare is a lifeline for millions of American seniors and Senator Manchin has always supported pathways to ensure it remains solvent,” said Sam Runyon, a spokeswoman for Mr. Manchin. “He remains optimistic there is a path to do just that.”

She cautioned that an overall deal on a broader climate, tax and spending package has yet to be struck. Some Democrats also hope to include an extension of expanded Affordable Care Act subsidies, which passed on a party-line vote in the $1.9 trillion pandemic aid package in 2021.

“Senator Manchin still has serious unresolved concerns, and there is a lot of work to be done before it’s conceivable that a deal can be reached he can sign onto,” Ms. Runyon said.

While Mr. Manchin has said he would support additional tax increases, any changes to the tax code must also win the support of Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, a centrist who opposed many of her party’s initial tax proposals.

And while many Democrats are anxious to address climate change before the midterm elections, which may change the balance of power in Washington, Mr. Manchin, who has been protective of his state’s coal industry, continues to haggle over that issue.

The heart of the climate plan is expected to be approximately $300 billion in tax credits to expand the development of clean energy like wind, solar and battery storage, a significantly smaller plan that reflects concessions to Mr. Manchin, according to several people familiar with the negotiations.

Negotiators are also considering tax credits to incentivize the purchase of electric vehicles, though it is unclear whether Mr. Manchin will support such a provision.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/07/us/politics/medicare-solvency-taxes.html

What’s Wrong With Health Insurance? Deductibles Are Ridiculous, for Starters.

by Aaron Carroll - NYT - July 7, 2022

More than 100 million Americans have medical debt, according to a recent Kaiser Health News-NPR investigation. And about a quarter of American adults with this debt owe more than $5,000. This isn’t because they’re uninsured. More often, it’s because they’re underinsured.

The Affordable Care Act was supposed to improve access to health insurance, and it did. It reduced the number of Americans who were uninsured through the Medicaid expansion and the creation of the health insurance marketplaces. Unfortunately, it has not done enough to protect people from rising out-of-pocket expenses in the form of deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance.

Out-of-pocket expenses exist for a reason; people are less likely to spend their own money than an insurance company’s money, and these expenses are supposed to make patients stop and think before they get needless care. But this moral-hazard argument assumes that patients are rational consumers, and it assumes that cost-sharing in the form of deductibles and co-pays makes them better shoppers. Research shows this is not the case. Instead, extra costs result in patients not seeking any care, even if they need it.

Cost-sharing isn’t set up in a thoughtful way such that it might steer people away from inefficient care toward efficient care. Deductibles are, frankly, ridiculous. The use of deductibles assumes that all medical spending is the same and that the system should disincentivize all of it, starting over each Jan. 1. There is no valid argument for why that should be. Flu season peaks in the winter. We were in an Omicron surge at the beginning of this year. Making that the time when people are most discouraged from getting care doesn’t make sense.

Co-pays and co-insurance aren’t much better. They treat all patients the same, and they assume that all patients should be treated the same way.

In a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper published last year, researchers looked at how increases in cost-sharing affected how older adults, who are more likely to need care, pay for and use drugs. Remember, people age 65 and older in the United States are insured with what most consider to be rather comprehensive coverage: Medicare. The researchers claimed, however, that a simple $10 increase in cost-sharing, which many would consider a small amount of money, led to about a 23 percent decrease in drug consumption. Worse, they said it led to an almost 33 percent increase in monthly mortality. In other words, making seniors pay $10 more per prescription led to people dying.

These seniors weren’t taking optional, esoteric, exceptionally expensive medications. This finding was for drugs that treat cholesterol and high blood pressure. In fact, they were considered “high value” drugs because they were proven to save lives. Further, those at higher risk of a heart attack or stroke were more likely to cancel their prescriptions than people at lower risk.

People are not smart shoppers or rational spenders when it comes to health care. When you make people pay more, they consume less care, even if it’s for lifesaving treatment.

Moreover, a $10 increase in drug cost-sharing is small potatoes compared with what most people have to pay out of pocket for care each year. The average deductible on a silver-level plan on the A.C.A. exchanges rose to $4,500 in 2021. If people tried to buy plans with a lower premium, at a bronze level, the average deductible rose to more than $6,000. Granted, some cost-sharing reductions are available for those who make less than 250 percent of the federal poverty line, but even after accounting for those, the average deductible was more than $3,100 for silver plans.

Those who receive insurance from their employers aren’t much better off than those who buy on the A.C.A. marketplaces. The average deductible for insurance offered by large companies in the United States was more than $1,200. At small companies, it was more than $2,000.

Those are only the deductibles. After they are paid, people must still cover co-pays and co-insurance until they hit the out-of-pocket maximums. The good news is that the A.C.A. limits these in plans sold in the exchanges. The bad news is that they’re astronomical: $8,700 for an individual and $17,400 for a family.

A large majority of Americans don’t have that kind of money sitting in accounts, certainly not after paying an average of about $5,000 in premiums each year for a benchmark individual silver plan. Half of U.S. adults don’t have even $500 to cover an unexpected bill. Anyone who requires significant health care will be out the entire deductible, meaning thousands of dollars, and if severely ill, is likely to hit the out-of-pocket maximum.

Of course Americans are in medical debt. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates the country’s collective medical debt is almost $200 billion.

It’s worth noting that the cost of health care in the United States is so high that even expensive premiums are not enough to cover the full amount without significant out-of-pocket spending. That doesn’t mean no better options exist for cost-sharing. We could treat those with diagnosed chronic diseases differently, as many countries in Europe do. It makes sense to try to disincentivize healthy people from overtreatment, but lots of people, including me, need care that costs money every day. It makes no sense to try to persuade me to rethink that. U.S. leaders could also consider adapting a reference pricing system, where the health system determines what constitutes the lowest-cost, highest-quality care and makes that available without any out-of-pocket spending. Cost-sharing can then be applied to other options that might cost more or have less evidence behind them.

The purpose of insurance is to protect people from financial ruin if they face unexpected medical expenses. Reducing the amount that they need to pay from six figures to five is necessary, but not sufficient. It’s not enough to give people insurance. That insurance must also be comprehensive.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/07/opinion/medical-debt-health-care-cost.html

California will make its own insulin to fight drug’s high prices, Newsom says

by Timothy Bella - Washinngton Post - July 8, 2022

California will start making its own affordable insulin as part of an effort to combat high drug prices for a lifesaving medication that has been made inaccessible for some Americans living with diabetes, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) announced Thursday.

Newsom said in a video posted to Twitter that $100 million from the state budget he recently signed for 2022-2023 would be allocated for California to “contract and make our own insulin at a cheaper price, close to at cost, and to make it available to all.” Half of the $100 million would go toward the development of a “low-cost” insulin, Newsom said. The other $50 million would go toward a facility in the state to manufacture insulin that would “provide new, high-paying jobs and a stronger supply chain for the drug.”

“California is going to make its own insulin,” Newsom said in the video. “Nothing epitomizes market failures more than the cost of insulin. Many Americans experience out-of-pocket costs anywhere from $300 to $500 per month for this lifesaving drug. California is now taking matters into our own hands.”

It’s unclear when the state’s insulin would be available or how much it would cost. A spokesman with the governor’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment early Friday.

The announcement out of California comes as top senators in Congress recently unveiled a bipartisan bill to curb the high cost of insulin, which has been decried for years by advocates, doctors and President Biden. The bill from Sens. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.) and Susan Collins (R-Maine) last month would place a $35 monthly cap on the cost of insulin for patients with private insurance as well as those enrolled in Medicare, although it wouldn’t afford the same protections to the uninsured. The bill also seeks to make insulin more accessible by cracking down on previous authorization requirements that can force patients to jump through hurdles to get insurers to help pay for medications.

Despite the pledge from Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) to bring the insulin pricing bill to a vote, the legislation faces difficulty passing in the chamber, as some Republicans have previously criticized the idea of a $35 cap as a price control.

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accounting for about 11 percent of the U.S. population. Even though more than 7 million Americans with diabetes are dependent on insulin each day, some Americans have struggled to keep up with the soaring costs of the drug, according to Yale researchers.

Since diabetics typically use two or three vials of insulin per month, costs can reach more than $6,000 annually for people with no insurance, inadequate coverage or high deductibles. Some of the list prices for the drug can range from $125 to more than $500. Humalog, a branded insulin drug that cost about $21 per vial when Eli Lilly introduced it in 1996, listed at the end of last year at about $275 in the United States.

A 2019 study published in the medical journal JAMA Internal Medicine found that the high costs for the drug had caused an estimated 1 in every 4 people with diabetes to skip doses or ration how much they took. Black, Latinx and Native American patients, who are less likely to have insurance or the level of insurance to cover the prices, are disproportionately affected by the high costs, research shows.

California’s push to make its own insulin isn’t the first time a state or group has tried to make the drug in response to the costs.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D) signed legislation in 2019 to cap insulin co-payments at $100 per month to those patients with private insurance. In response to the high costs this year, Civica Rx, the nonprofit company for a consortium of large U.S. hospitals, said in March it planned to manufacture and sell generic versions of insulin at no more than $30 per vial and $55 for five injector-pen cartridges. Civica Rx said it expects to begin selling insulin in 2024, once it completes construction of a 140,000-square-foot pharmaceutical plant in Petersburg, Va. — and if it wins licensing from the Food and Drug Administration.

Newsom signed the $308 billion state budget on June 30. Included in the budget was a $17 billion relief package to give “inflation relief” checks as high as $1,050 to residents to address concerns surrounding the nation’s highest average gas prices. The plan would also suspend California’s sales tax on diesel fuel and give additional aid for residents who need help with rent and utility bills, according to lawmakers.

California has the highest number of new diabetes cases among all states, according to the governor’s office. Ethnic minorities, the elderly, men and the poor are most affected by diabetes in California, according to the state.

The governor said in a news release last week that the budget investing $100 million in insulin is in place to “develop and manufacture low-cost biosimilar insulin products to increase insulin availability and affordability in California.”

“In California, we know people should not go into debt to receive lifesaving medication,” Newsom said in the video.

America Was in an Early-Death Crisis Long Before COVID

by Ed Yong - The Atlantic - July 21, 2022

Jacob Bor has been thinking about a parallel universe. He envisions a world in which America has health on par with that of other wealthy nations, and is not an embarrassing outlier that, despite spending more on health care than any other country, has shorter life spans, higher rates of chronic disease and maternal mortality, and fewer doctors per capita than its peers. Bor, an epidemiologist at Boston University School of Public Health, imagines the people who are still alive in that other world but who died in ours. He calls such people “missing Americans.” And he calculates that in 2021 alone, there were 1.1 million of them.

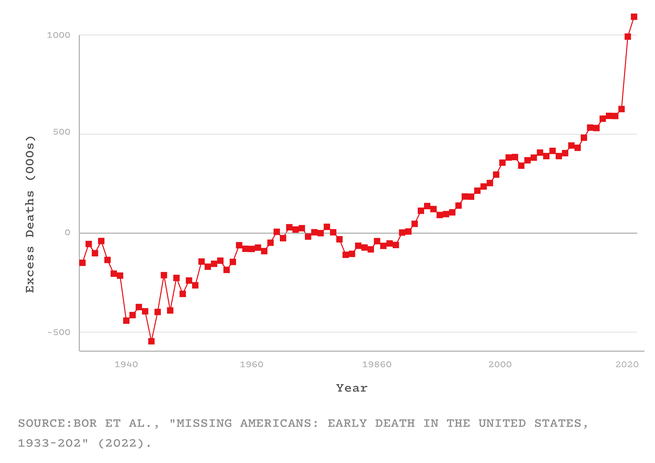

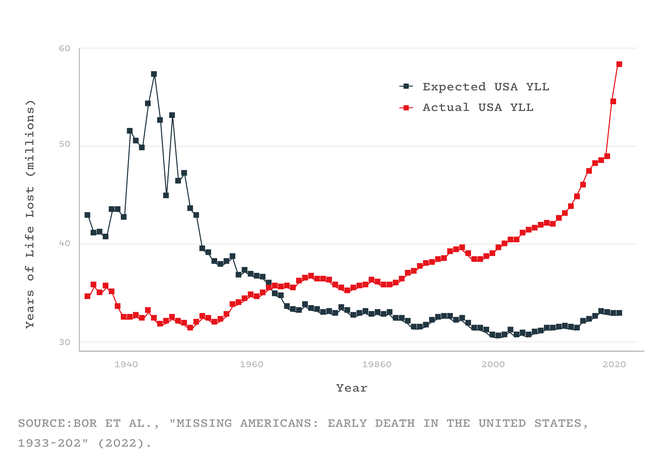

Bor and his colleagues arrived at that number by using data from an international mortality database and the CDC. For every year from 1933 to 2021, they compared America’s mortality rates with the average of Canada, Japan, and 16 Western European nations (adjusting for age and population). They showed that from the 1980s onward, the U.S. started falling behind its peers. By 2019, the number of missing Americans had grown to 626,000. After COVID arrived, that statistic ballooned even further—to 992,000 in 2020, and to 1.1 million in 2021. Were the U.S. “just average compared to other wealthy countries, not even the best performer, fully a third of all deaths last year would have been prevented,” Bor told me. That includes half of all deaths among working-age adults. “Think of two people you might know under 65 who died last year: One of them might still be alive,” he said. “It raises the hairs on the back of my neck.”

These counterfactuals puncture two common myths about America’s pandemic experience: that the U.S. was just one unremarkable victim of a crisis that spared no nation and that COVID disrupted a status quo that was strong and worth restoring wholesale. In fact, as one expert predicted in March 2020, the U.S. had the worst outbreak in the industrialized world—not just because of what the Trump and Biden administrations did, but also because of the country’s rotten rootstock. COVID simply did more of what life in America has excelled at for decades: killing Americans in unusually large numbers, and at unusually young ages. “I don’t think people in the United States actually have any awareness of just how poorly we do as a country at letting people live to old age,” Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota, told me.

Although Bor’s study has yet to be formally reviewed, Wrigley-Field and five other independent researchers vouched for its quality to me. “The paper is extremely important, and the researchers who produced this know what they’re doing,” Steven Woolf, a population-health expert at Virginia Commonwealth University, told me. “It builds on, and considerably expands, what we’ve already known.”

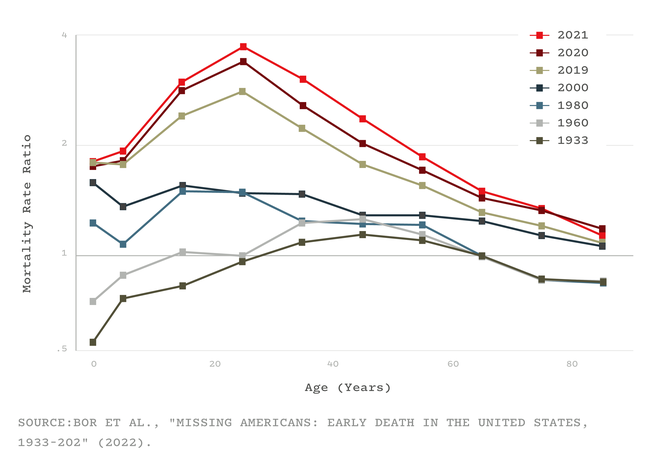

Several studies, for example, have shown that America’s life expectancy has tailed behind other comparable countries since the 1970s. By 2010, that gap was already 1.9 years. By the end of 2021, it had grown to 5.3. And although many countries took a longevity hit because of COVID, America was once again exceptional: Among its peers, it experienced the largest life-expectancy decline in 2020 and, unlike its peers, continued declining in 2021. But Bor says that people often misinterpret life-expectancy declines, as if they simply represent a few years shaved off the end of a life. Someone might reasonably ask: What’s the big deal if I die at 76 versus 78? But in fact, life expectancy is falling behind other wealthy nations in large part because a lot of Americans are dying very young—in their 40s and 50s, rather than their 70s and 80s. The country is experiencing what Bor and his colleagues call “a crisis of early death”—a long-simmering tragedy that COVID took to a furious boil.

In every country, the coronavirus wrought greater damage upon the bodies of the elderly than the young. But this well-known trend hides a less obvious one: During the pandemic, half of the U.S.’s excess deaths—the missing Americans—were under 65 years old. Even though working-age Americans were less likely to die of COVID than older Americans, they fared considerably worse than similarly aged people in other countries. From 2019 to 2021, the number of working-age Americans who died increased by 233,000—and nine in 10 of those deaths wouldn’t have happened if the U.S. had mortality rates on par with its peers. “This is a damning finding,” Oni Blackstock, the founder and executive director of Health Justice, told me.

Read: How did this many deaths become normal?

The crisis of early death was evident well before COVID. As many studies and reports have shown, since the turn of the 21st century, “midlife ages are where health and survival in the U.S. really go off the rails,” Wrigley-Field told me. “The U.S. actually does well at keeping people alive once they’re really old,” she said, but it struggles to get its citizens to that point. They might die because of gun violence, car accidents, or heart disease and other metabolic disorders, or drug overdoses, suicides, and other deaths of despair. In all of these, the U.S. does worse than most equivalent countries, both by failing to address these problems directly and by leaving people more vulnerable to them to begin with.

Consider how many years the missing Americans would have collectively enjoyed had they survived—all the birthdays and anniversaries that never happened. In other rich countries, the total “years of life lost” have flatlined for the past five decades. In the U.S., they have soared: In 2021 alone, the 1.1 million missing Americans lost 25 million years of life among them. That number doesn’t account for the events that preceded many of these deaths—the “years of disability, illness, and loss of human potential, creativity, and dignity,” Laudan Aron, a health-policy researcher at the Urban Institute, told me. And, especially in the case of middle-aged deaths, they left behind young dependents, whose own health might suffer as a result. The sheer number of missing Americans, and the “profound ripple effects” of their absence, are “really hard to wrap one’s head around,” Aron said.

Read: The final pandemic betrayal

These staggering numbers also help contextualize COVID’s toll. The coronavirus caused the largest single-year rise in mortality since World War II, becoming the third leading cause of death in the U.S., after only heart disease and cancer. But this enormous tragedy unfolded against an already tragic backdrop: The number of missing Americans from 2019 is larger than the number of people who were killed by COVID in 2020 or 2021. This isn’t to minimize COVID’s impact; it simply shows that in the Before Times, America had “very successfully normalized to an extremely high level of death on the scale of what we experienced in the pandemic,” Justin Feldman, a social epidemiologist at Harvard, told me. And when COVID drove those levels skyward, America proved that “we’ll accept even more deaths compared to our already poor historical norms,” Feldman said.

Such deaths, though obvious on a graph, are hidden from Americans with social privilege. In the summer of 2020, Bor remembers having an outdoor barbecue with a friend who grew up in a low-income housing project. “At that point, six months in, he knew six people in his close circle who had been killed by COVID,” Bor told me. “I still don’t.” The fact that half of the working-age Americans who died last year should still be alive “isn’t visceral if you haven’t lost anyone,” he said.

The current mortality crisis was long in the making. In terms of mortality, America’s peer countries—many of which had been hammered by World War II and its aftermath—began catching up with it in the mid-1970s before overtaking in the early 1980s. That was a pivotal era, when globalization, automation, and a growing service industry led to huge losses in mining, manufacturing, and other blue-collar sectors. The U.S. profoundly failed to protect its citizens from these changes. Its social safety net—state assistance for parents, or people facing job, food, or housing insecurity—was meager; its public-health system was languishing after decades of underinvestment; and unlike every other wealthy country, it lacked universal health care. These factors “privatized risk,” Bor and his colleagues wrote in their paper, “tying health more closely to personal wealth and employment.” As labor unions declined and minimum wages stagnated, more Americans had fewer resources to lean on if their health declined. Poorer Americans already lived, on average, shorter lives than rich ones, and that gulf started to widen.

Other particularly American choices exacerbated the stresses on the health of the country’s citizens, again weighing more heavily on less wealthy people. A growing mass-incarceration industry punished them. A deregulatory agenda that began with Ronald Reagan’s administration left them vulnerable to unhealthy foods, workplace hazards, environmental pollutants, guns, and opioids. “America basically says: If you’re poor, you don’t have access to safe choices,” Bor told me.

Factors like social inequalities and frayed social safety nets are the fundamental weaknesses of American society, which more specific problems like opioids, metabolic disorders, and COVID exploit. During the pandemic, for example, poor and minority groups were more likely to be infected because they lived in crowded housing, distrusted medical leaders, and couldn’t work from home or take time off when sick. And instead of addressing these foundational problems, policy makers instead focused on personal responsibility.

America’s drastic underperformance in health also stems from its history of segregation and discrimination. Racist policies have obviously harmed the health of minorities. But as the policy expert Heather McGhee and the physician Jonathan Metzl have independently argued, elites have long marshaled the racial resentment of poor white Americans to undermine support for public goods that would benefit everyone, such as universal health care. Per Frederick Douglass and other Black leaders, “They divided both to conquer each.”

Read: How public health took part in its own downfall

COVID, for example, disproportionately killed Black, Latino, and Indigenous Americans—a trend that, when highlighted to white people, reduces their concern about the pandemic and their support for safety measures. But in 2021, young white Americans still died at three times the rate of the average resident of other peer nations, while young Black and Indigenous Americans died at rates five- and eightfold higher, respectively. “There are thousands of racial-disparity studies that compare Black people to white people—but white Americans are a terrible counterfactual,” Bor told me. They’re frogs in the same pot, boiling more slowly but boiling nonetheless. By using them as a baseline, we ignore how “everyone is harmed by the status quo in the U.S.,” Blackstock told me, while also underestimating how dire things really are for people of color. (The same problem applies to income inequality: White Americans living in the richest 1 percent of counties still have higher rates of maternal and infant mortality than the average residents of wealthy countries.)

So, “what happens now?” Bor asked me. “Are we going to have 1 million missing Americans a year, every year, going forward? Or more?” His study doesn’t suggest a reason for optimism, but it does provide a defense against nihilism. The entire concept of missing Americans is rooted in a comparison with other countries, which shows that these early deaths aren’t inevitable. The U.S. could at least start moving in the direction of its peers by adopting policies that work elsewhere, such as universal health care, minimum-wage increases, federally required paid sick leave, and better unemployment insurance.

But “the inability of our politics to generate policies that manage health threats is grim,” Bor said. None of the weaknesses that COVID exposed have been addressed; some, like the chasm-sized health gaps between rich and poor or white and Black, have been widened. Vaccines significantly reduce the risk of dying from COVID, but their power is blunted by low uptake, new variants, the lifting of almost all infection-thwarting protections, and the looming loss of COVID funding. Reactionary laws that hamstring what public-health departments can do in emergencies will make the U.S. vulnerable to the new viruses that will inevitably assault it in future years. America’s already underperforming health-care system has been badly battered by the pandemic, and weakened by waves of health-care-worker resignations. In recent months, the Supreme Court has constrained both gun and carbon-emission regulations, while clearing the road for states to restrict or ban abortions—a move that could easily boost America’s already sky-high maternal mortality rates. The climate is still changing rapidly, exposing people who have no choice but to work outside to the ravages of heat.

As much of the country returns to normal, Bor’s study makes plain what normal actually meant—and, as I wrote in 2020, that normal led to this. “A lot of Americans may be under the impression that we had a bad go of it during COVID, and once the pandemic is over, they can go back to having the best health in the world,” Woolf told me. “That is a gross misconception.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2022/07/us-life-span-mortality-rates/670591/

For Monkeypox Patients, Excruciating Symptoms and a Struggle for Care

by Sharon Otterman - NYT - July 18, 2022

Although he was covered with lesions, it took four hours of phone calls, and then five hours in a Harlem emergency room, for Gabriel Morales to be tested for the monkeypox virus earlier this month. And that was just the beginning of his wait.

Mr. Morales was sent home and told the Department of Health would call with his results in less than a week. The call never came.

He spent the next eight days alone in his apartment in what he described as excruciating pain, trying to find someone to prescribe him pain medication and a hard-to-access antiviral drug.

As time passed, the disorganization in the public health response disturbed him more and more: the city’s vaccine website glitches; a vaccine rollout that seemed designed to reach the privileged and that turned him away; an opaque process to access medicine that he believed could help, but that he couldn’t find.

When he received a $720 bill for his emergency room visit, it felt like more than incompetence. It felt like a lack of compassion.

“I understand that this is new — but it is urgent,” said Mr. Morales, 27, who was eventually prescribed the antiviral drug to help with his symptoms. His test, he found out after 10 days, had never been picked up from the hospital. “It was just the worst pain I’ve experienced in my life.”

While monkeypox can sometimes result in mild symptoms, it is turning out to be unexpectedly severe for a substantial number of patients infected in this outbreak, according to doctors, public health officials and patients in New York City, the epicenter of the nation’s cases.

Beyond the very public shortcomings in the government’s vaccination efforts are the private struggles of the men infected with the disease who have found care hard to come by. Internal lesions in the anus, genitals and mouth can be particularly painful, and there is growing concern that they may cause debilitating scarring.

“What many of us learned in medical schools is that monkeypox is a mild, self-limiting illness,” said Dr. Mary Foote, medical director of the office of emergency preparedness and response at the city’s Department of Health, speaking at a Thursday briefing hosted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “But the reality on the ground is that a lot of people with this infection are really suffering.”

What’s also striking, she said, about this outbreak, is “how many of these patients have had difficulty getting the care they need to treat these symptoms.”

Monkeypox, endemic in parts of Africa for decades, has been spreading globally since early May through networks of men who have sex with men, probably sparked by transmission at one or more raves in Europe, researchers believe. The disease, which mostly transmits though intimate, skin-to-skin contact, has resulted in fatalities in Africa, but no one has yet died of the disease in the United States.

The first American case was recorded on May 18. There have now been more than 1,800 cases, affecting almost every state. Experts are concerned that if the outbreak is not contained, the virus will persist and spread more widely.

In New York City, cases have nearly tripled over the past week to 461 total cases on July 15, up from 160 on July 8. While some of that increase stems from expanded testing capacity and awareness, the spread of the disease in the city is “exponential,” said Dr. Foote, and is likely to continue for a while.

The unexpected severity of symptoms is making patients’ encounters with an overburdened health care system that was not prepared for this outbreak even more difficult. Interviews with six recent and current monkeypox patients in New York City, and three in other cities across the country, suggest that the public health response has been slow and underresourced at every level, from testing to treatment to vaccination.

Another of those patients, Sebastian Kohn, 39, felt exhausted and feverish through much of the July 4 weekend and had painful, swollen lymph nodes. Then the rash started.

Mr. Kohn, who lives in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, has private health insurance, so he went to a local urgent care to get tested while dizzy with a 103-degree fever. But he was not prescribed anything stronger than Tylenol for the pain. “The most painful thing are the anal rectal lesions,” he said. “They are just excruciating.”

Ultimately, he said, lidocaine helped, but for a week, no one prescribed it to him.

Both Mr. Morales and Mr. Kohn are sexually active gay men, as are most patients so far in the outbreak in New York and beyond. Within that group, privilege and know-how has helped some people find care faster than others.

Sign up for the New York Today Newsletter Each morning, get the latest on New York businesses, arts, sports, dining, style and more.

A lawyer who asked to be identified by his initial, M., to protect his medical privacy, said he went into full litigator mode after a sexual partner called him on June 15 to tell him he had monkeypox.

M. was able to get a first vaccine dose at Bellevue, the city’s main public hospital and a hub of its monkeypox response, by showing up and insisting. After he tested positive despite the dose, he was able to get the sought-after antiviral drug, TPOXX, which relieves symptoms but requires special approval for each patient, because one medical practice helped.

“It was still horrible but I was lucky,” he said. “I’m just worried about everybody else.”

Mr. Kohn also eventually received TPOXX, but only after an exhausting process.

The urgent care center where he had been tested told him to call the Department of Health. The Department of Health told him he had to be referred by his primary care doctor. His doctor’s office told him to speak to the health department.

Eventually, he received a call back from a sexual health clinic affiliated with NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, which said someone at the health department had referred him. “It’s just no coordination at all,” he said. “It’s just not fair to have patients who are severely ill run in circles to organize their own care.”

TPOXX, or tecovirimat, which was originally developed in case of a smallpox bioterrorism incident, is only available for monkeypox treatment through a compassionate-use protocol, which requires submitting hours of paperwork to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for each patient. It is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of monkeypox, though anecdotally it is showing positive results, clinicians say.

Providers and local health officials are pushing the federal government to open up access to the drug.

“This is not a mild disease, for a percentage of people it is much more worse than I would have anticipated,” said Dr. Jason Zucker, an infectious disease specialist at the NewYork-Presbyterian clinic.

His clinic has given the antiviral to 26 patients so far, he said. Citywide, 70 prescriptions have been written, Dr. Foote said.

“As a city and a system, we are still really struggling to meet the demand,” she said.

Sergio Rodriguez, 39, is a queer trans man who lives on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Because he was already a patient at Callen-Lorde, a well-known sexual health clinic, he was able to quickly get an appointment to be swabbed there for lesions on July 5. But his results never came back, either.

A week after his test, he did receive a call from the Health Department — but it was a contact tracer telling him he had been exposed to someone else with the virus. Mr. Rodriguez told the tracer he was living with his immunocompromised, 76-year-old father, and that he desperately needed him vaccinated.

Finally, on July 15, the department called his father to arrange for his vaccination.

Mr. Rodriguez was frustrated with the response. “In my experience, especially as a trans Latino person in New York City, my health and my concerns are not going to be emphasized,” he said. “Things are going to go to people that have more access and that have more strings to pull and also who are of a different socioeconomic class.”

Dr. Foote said the Health Department is well aware of the difficulties people are having in accessing care. City health officials are trying to push the federal government for more vaccines and access to TPOXX and are concerned about equity in distributing it. Mayor Eric Adams recently wrote a letter to President Biden asking for more vaccines.

In recent weeks, aspects of the response have improved. Testing capacity has grown after LabCorp, a commercial lab, began offering tests. Vaccines have begun to flow into the city in greater numbers, though demand still far outstrips supply. On Friday, 9,200 vaccine appointments were booked in seven minutes, the city said.

The city has also been working to improve its vaccine rollout system, reserving some doses for distribution through community providers and developing a mass vaccination plan. And education among health care providers, though still uneven, has been growing: L.G.B.T.Q. health organizations have held webinars, and the city has issued treatment guidance to providers.

Eli, 28, a Chelsea resident who works in nightlife and asked to be identified by his nickname to protect his medical privacy, was among the first in New York to test positive for monkeypox. He came down with a fever on June 22 and began noticing anal pain the next day, as did three friends he had been sexually active with on Fire Island.

The next day, he went to the Chelsea Sexual Health Clinic, where he was told by two providers that he most likely had a different sexually transmitted disease, not monkeypox.

By Sunday night, the pain had increased so much that he and his friends went to an urgent care clinic in Union Square. The doctor at first refused to test him for monkeypox, he said, but eventually agreed to submit photos of his lesions to the Department of Health.

He said the Health Department called five days later with his results, and that, after he pushed, the contact tracer gave him the cellphone number for the Department of Health’s head of bioterrorism. That connection helped him obtain shots for 26 close contacts — friends and people he works with in nightlife who he knew were at high risk.

Though his own case was relatively mild, Eli said he has found it very upsetting to watch the government flub its virus response. He has known from the beginning, he said, that it probably wasn’t going to go well.

“‘Y’all are being dumb about this,’” he recalled yelling at the Health Department tracer. “‘This is going to be bad.’”

BC Court of Appeal strengthens landmark ruling defending public health care in Canada

Today’s ruling from the BC Court of Appeal in the Cambie Surgeries Corporation (CSC) case has upheld the BC Supreme Court’s September 2020 decision that protected key principles of public health care in Canada.

The court found that the provisions of the Medicare Protection Act challenged by Cambie Surgeries are “necessary to preserve a publicly funded system delivering necessary services based on need and not ability to pay”, and that “suppressing all private care is necessary to meet that objective”. This decision comes at a time when all efforts need to be made to strengthen and enhance our public health care system rather than dismantle it.

CEO of CSC Dr. Brian Day and his powerful allies have been dealt yet another blow in their more than a decade-long attempt to use the courts to undermine public health care in Canada and usher in a profit-driven health care system.

“As a group of patients, doctors and health care advocates, we became involved in this case in order to defend and protect public health care and our resolve remains as strong today as the day it started,” said Tuesday Andrich, Co-Chair of the BC Health Coalition. “With today’s ruling confirming the strength of the BC Supreme Court decision, we can get back to the important work of improving our health care system with public solutions that address the real challenges our health care system is facing.”

The Court has upheld BC Supreme Court Justice Steeves’ conclusions that the evidence at trial showed that duplicative private health care would increase wait times as well as his conclusions about the harm this would cause to vulnerable people who depend upon the public system.

“There is no question that our public health care system is currently under strain, and we need all hands on deck to work together to strengthen and improve it,” said Dr. Melanie Bechard, Chair of Canadian Doctors for Medicare. “There are efficient, evidence-based solutions that are proven to reduce wait times and improve the quality of care in an equitable way. Allowing doctors to charge patients as much as they want, and forcing patients to pay out-of-pocket or purchase private insurance is not one of them.”

The past two years have underscored just how important it is that our public health care system is there for everyone when they need it. This decision protects our ability to care for one other today and into the future.

How do we ‘fix’ Canadian health care? Not by forcing patients to pay

If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that we need our publicly funded health care system to be there for all of us.

Nobody denies that our health care system is under immense pressure right now. About 15 per cent of Canadians — 5,000,000 of us — don’t have a regular primary care provider, which leads to many patients spilling over into emergency departments, sometimes waiting days for a bed. Wait times for elective surgeries are longer than usual, with millions of procedures having been postponed or cancelled because of the pandemic.

Chronic understaffing made worse by the pandemic means that health workers are experiencing burnout and emotional exhaustion at record levels and some are making the difficult decision to leave their professions.

To solve these issues we need to strengthen, not dismantle, our publicly funded health care system.

It is dangerous to say we should “fix” our problems with private pay health care. Why? Because public funding isn’t the cause of our problems. The Supreme Court of British Columbia made this abundantly clear in 2020 when it ruled against the Cambie Surgery Corporation’s attempt to overturn key provisions of B.C.’s Medicare Protection Act, including the part that prevents doctors from billing both government and patients for medically necessary care.

Sure, private pay might give faster access to those who can afford to pay, but it would also poach doctors, nurses and other highly skilled workers from the public system, where they are desperately needed. And with the costs of everyday essentials like groceries and gas skyrocketing and record-high inflation, it is especially cruel to promote solutions that would force people to pay for medical care.

Canada is not alone in facing this challenge. All health-care systems around the world have been pushed to the brink during the pandemic. All countries are dealing with backlogs and trying to manage wait lists. Even countries with a multi-payer system, like Australia, have rapidly growing wait lists — so creating a parallel private pay system clearly won’t solve our problems either.

The bottom line is that publicly funded solutions are required to improve access to care for the many, not the few.

So let’s focus on proven innovations and systemic changes that will increase capacity in the public health care system; things like centralized wait lists for the next available surgeon and expanding operating room schedules in order to tackle surgical backlogs and reduce wait times.

We can alleviate the strain on our emergency departments by urgently investing in a strong primary care system — the foundation upon which our entire health care system is built — to address the root causes of what sends patients to the ER in the first place. We can provide better care in the community and end decades of penny-pinching for home care and long-term care — respecting older adults’ wishes to “age in place.”

By expanding access to publicly delivered dental care, implementing universal pharmacare and addressing the social determinants of health, we can improve the overall health of our communities, which will in turn further alleviate some of the strain our system is feeling.

We must build up our health care workforce in a proactive and sustainable way. Governments can tackle this with solutions to improve working conditions (e.g. fair wages, benefits, less involuntary part-time work), implementing national licensure so doctors and nurses can practice anywhere in Canada and credentialing internationally trained health professionals.

With Canada’s premiers set to meet in Victoria, B.C., we are likely to hear them ask for significant increases to federal transfer payments for health care. But is more money, alone, good enough? While we undoubtedly need to invest more public funds in our health care system, we need to do it transparently and strategically.

Premiers and provincial/territorial health ministers need to be held accountable to implement solutions that will reduce wait times for care. The federal government can also play a more active role in guaranteeing timely access to high-quality care from coast to coast to coast.

Those looking to hand our health care system to corporate investors see a lucrative opportunity in private pay health care. It’s a seemingly simple and neat solution — but it’s wrong. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that we need our publicly funded health care system to be there for all of us.

We cannot afford to look back on this time in future years and wish we’d done more to rebuild medicare when it was in crisis. We need politicians of all stripes to come to the table with commitment, courage, and action. The time is now.

Katie Arnup (@Karnup) is the executive director of Canadian Doctors for Medicare (@CdnDrs4Medicare).Dr. Amit Arya (@AmitAryaMD) is a palliative care physician, researcher, educator and board member with Canadian Doctors for Medicare.