Editor's Note -

One of the clearest and most concise sources of information about "Medicare for All" and for the cases for and against it

I've seen is a newly published pamphlet, the latest in a series by Dr. John Geyman. He has modeled it after the famous series of pamphlets written by Thomas Paine in the 18th century regarding American Independence.

It is titled "Common Sense: The Case For And Against Medicare For All - Leading Issue in the 2020 Elections."

In it, he discusses:

What is Single-Payer Medicare for All!

The Case for Expanded & Improved Medicare for All

The Case against Medicare for All, including rebuttal of Myths

How Should We Decide?

Useful Resources

It will take you about 15 minuters to read and is available from Amazon for $5.95. Here is the link to it.

https://www.amazon.com/Common-Sense-Case-Against-Medicare/dp/193821823X/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1FPJBLGVA6DBI&keywords=common+sense+the+case+for+and+against+medicare+for+all&qid=1560946363&s=gateway&sprefix=common+sense+the+case+%2Caps%2C162&sr=8-1

-SPC

Trump Wants to Neutralize Democrats on Health Care. Republicans Say Let It Go.

By Peter Baker, Michael Tackett and Linda Qiu - NYT - June 16, 2019

WASHINGTON — As President Trump prepares to kick off his

bid for a second term this week, he is anxiously searching for a way to

counter Democrats on health care, one of their central issues, even

though many of his wary Republican allies would prefer he let it go for

now.

Since he announced his previous run four years ago, Mr. Trump has promised to replace President Barack Obama’s health care law with “something terrific” that costs less and covers more without ever actually producing such a plan.

Now he is vowing to issue the plan within a month or two, reviving a campaign promise with broad consequences for next year’s contest. If he follows through, it could help shape a presidential race that Democrats would like to focus largely on health care.

While the president has acknowledged that no plan would be voted on in Congress until 2021, when he hopes to be in a second term with Republicans back in charge of the House, he is gambling that putting out a plan to be debated on the campaign trail will negate some of the advantage Democrats have on the issue.

Since he announced his previous run four years ago, Mr. Trump has promised to replace President Barack Obama’s health care law with “something terrific” that costs less and covers more without ever actually producing such a plan.

Now he is vowing to issue the plan within a month or two, reviving a campaign promise with broad consequences for next year’s contest. If he follows through, it could help shape a presidential race that Democrats would like to focus largely on health care.

While the president has acknowledged that no plan would be voted on in Congress until 2021, when he hopes to be in a second term with Republicans back in charge of the House, he is gambling that putting out a plan to be debated on the campaign trail will negate some of the advantage Democrats have on the issue.

But

nervous Republicans worry that putting out a concrete plan with no

chance of passage would only give the Democrats a target to pick apart

over the next year. The hard economic reality of fashioning a plan that

lives up to the promises Mr. Trump has made would invariably involve

trade-offs unpopular with many voters.

“Obamacare has been a disaster,” Mr. Trump told ABC News in an interview aired on Sunday evening. His own plan, he insisted, would lower costs. “You’ll see that in a month when we introduce it. We’re going to have a plan. That’s subject to winning the House, Senate and presidency, which hopefully we’ll win all three. We’ll have phenomenal health care.”

The president’s renewed interest in health care comes as he plans an elaborate rally in Orlando, Fla., on Tuesday to open a re-election campaign that is already struggling to find its bearings. After last week’s leak of a series of dismal internal poll results from March showing him trailing in multiple battleground states, Mr. Trump first denied that the surveys even existed, only to have his campaign later confirm that they in fact were real.

By Sunday, the episode had led to a purge as the Trump campaign indicated that it would cut ties with three of its five pollsters, a sign of internal discord in an operation seeking to be far more organized and professional than the slapdash, one-man show that Mr. Trump ran out of Trump Tower in New York four years ago.

Democratic leaders have argued that they won control of the House in last year’s midterm elections in large part on the health care issue, and they have been pressing the point in recent weeks. Over the weekend, 140 House Democrats, more than half of the party’s caucus, held events or online town halls to talk about health care, their largest coordinated action in districts since winning the majority.

“Obamacare has been a disaster,” Mr. Trump told ABC News in an interview aired on Sunday evening. His own plan, he insisted, would lower costs. “You’ll see that in a month when we introduce it. We’re going to have a plan. That’s subject to winning the House, Senate and presidency, which hopefully we’ll win all three. We’ll have phenomenal health care.”

The president’s renewed interest in health care comes as he plans an elaborate rally in Orlando, Fla., on Tuesday to open a re-election campaign that is already struggling to find its bearings. After last week’s leak of a series of dismal internal poll results from March showing him trailing in multiple battleground states, Mr. Trump first denied that the surveys even existed, only to have his campaign later confirm that they in fact were real.

By Sunday, the episode had led to a purge as the Trump campaign indicated that it would cut ties with three of its five pollsters, a sign of internal discord in an operation seeking to be far more organized and professional than the slapdash, one-man show that Mr. Trump ran out of Trump Tower in New York four years ago.

Democratic leaders have argued that they won control of the House in last year’s midterm elections in large part on the health care issue, and they have been pressing the point in recent weeks. Over the weekend, 140 House Democrats, more than half of the party’s caucus, held events or online town halls to talk about health care, their largest coordinated action in districts since winning the majority.

In particular, Democrats hammered the Trump administration for asking a court in March to overturn the entire Affordable Care Act,

which among other things would eliminate protections for patients with

pre-existing conditions. Mr. Trump has repeatedly said he favors such

protections but has not explained how he would achieve them if the

Obama-era law were invalidated.

“The Trump administration is currently suing to eliminate the law that guarantees health care coverage for Americans with pre-existing conditions,” said Representative Ted Lieu of California, a leader of the Democratic committee that organized the weekend activities. “That action speaks for itself. If Trump wants to be serious about health care, he needs to stop the lawsuit and his other actions that seek to sabotage the A.C.A.”

While House Democrats advance incremental measures on health care, some prominent liberals, including presidential candidates like Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, have proposed a single-payer government-run health care plan that they call “Medicare for all,” hoping to capitalize on the popularity of the program for the elderly by expanding it to the population at large.

Mr. Trump and other Republicans see that as an opening for them on the campaign trail by characterizing it as socialism. Such a huge shift in how health care is run in the United States would not only put the government in charge, they say, but also cost enormous amounts of taxpayer money and force Americans to give up private insurance coverage they might like.

Mr. Sanders was pressed on those criticisms during an appearance on “Fox News Sunday” and argued that the current system was unsustainable, implicitly offering his own criticisms of the program erected by Mr. Obama from the left.

When

they were in the majority, House Republicans voted dozens of times to

repeal the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, only to see

their legislation die in the Senate. On one occasion, Mr. Trump summoned

House Republicans to the White House for a grand ceremony only to see

that momentum quickly fade away.

Mr. Trump often laments the failure by blaming Senator John McCain, Republican of Arizona, who voted against one repeal effort in the summer of 2017. Even if Mr. McCain had voted for the bill, however, full repeal of the Affordable Care Act would not have been assured.

That version would have eliminated the individual and employers’ mandate, but left intact the health care law’s Medicaid expansion and insurance regulations. And it would still have required passage in the House or forced lawmakers from both chambers to negotiate their differences.

When Mr. Trump pushed the idea of voting to repeal the law again recently, he was quickly dissuaded by Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the majority leader, who argued that comprehensive health care legislation would go nowhere in Congress. The president then insisted it was never his intention to vote on a bill before the 2020 election.Even as Mr. Trump has delayed producing a plan, he has continued to criticize the existing health care law, repeatedly claiming that it had become unaffordable because of average deductibles exceeding $7,000 or $8,000. This was an exaggeration.

Deductibles vary greatly by the type of plan and the enrollee. While deductibles for some plans can top $7,000, they average $4,375 for silver-tier plans, the most common choice for consumers. And those who receive cost-sharing reductions have lower deductibles still. Also left unsaid was his own administration’s role in causing higher deductibles, as the federal government sets caps on out-of-pocket costs and has increased the limit this year.

Midway through his third year in office, many remain skeptical that Mr. Trump will produce the plan he is now promising to unveil in a month or two.

“He can’t deliver the impossible,” said Len M. Nichols, the director of the Center for Health Policy Research and Ethics at George Mason University, “so he avoids specifics and postpones actually reckoning with a serious legislative proposal of his own.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/16/us/politics/trump-health-care-democrats-2020.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

“The Trump administration is currently suing to eliminate the law that guarantees health care coverage for Americans with pre-existing conditions,” said Representative Ted Lieu of California, a leader of the Democratic committee that organized the weekend activities. “That action speaks for itself. If Trump wants to be serious about health care, he needs to stop the lawsuit and his other actions that seek to sabotage the A.C.A.”

While House Democrats advance incremental measures on health care, some prominent liberals, including presidential candidates like Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, have proposed a single-payer government-run health care plan that they call “Medicare for all,” hoping to capitalize on the popularity of the program for the elderly by expanding it to the population at large.

Mr. Trump and other Republicans see that as an opening for them on the campaign trail by characterizing it as socialism. Such a huge shift in how health care is run in the United States would not only put the government in charge, they say, but also cost enormous amounts of taxpayer money and force Americans to give up private insurance coverage they might like.

Mr. Sanders was pressed on those criticisms during an appearance on “Fox News Sunday” and argued that the current system was unsustainable, implicitly offering his own criticisms of the program erected by Mr. Obama from the left.

“You have a dysfunctional health care system,” he said. “You’ve

got 70 million Americans who either have no health insurance or they are

underinsured with high deductibles and co-payments. We are paying twice

as much as any other country on earth for the prescription drugs that

we need. We spend far more per capita on health care as do the people of

any other country.”

Democrats enjoy a strong edge

with voters on health care, with 40 percent trusting them on the issue,

compared with 23 percent who trust Republicans more, according to an April poll by The Associated Press and the NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

Forty-two percent of Americans in that survey favored a single-payer system along the lines of what Mr. Sanders is proposing, while 31 percent opposed it and 25 percent did not take a position. Views of the Affordable Care Act are split right down the middle, with 50 percent approving of it and 48 percent disapproving of it in an April poll by Gallup.

Given the Democratic advantage, many Republicans say they should not focus their energy on health care but instead emphasize immigration and other issues where they are stronger. But the president and his team counter that even if they cannot win on health care, it would be ridiculous to simply cede the territory if they could at least narrow the gap.

The president feels compelled to have something specific to counter Medicare for all. Still, people close to Mr. Trump suggested that if he did release something within a month or two, it might not be a comprehensive plan but a series of smaller proposals that would potentially help, such as ideas for bringing down prescription drug costs, for giving states more flexibility on Medicaid expansion and for promoting more access in the marketplace.

Among those who are said to be influencing the discussion within the administration are Alex M. Azar II, the secretary of health and human services; Seema Verma, the head of the agency that runs Medicare and Medicaid; and Joe Grogan, the director of the White House Domestic Policy Council.

“The president has repeatedly promised something better than the A.C.A. but has never come up with a plan himself, and the congressional plans he endorsed were definitely not better for everyone,” said Larry Levitt, a senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“There’s always a tension for presidents around whether to submit a specific proposal to Congress or let the legislative process play out,” Mr. Levitt added. “When it comes to health care, the challenge has been that the president has not only avoided proposing a specific plan, but has made promises that no plan could ever fulfill.”

Forty-two percent of Americans in that survey favored a single-payer system along the lines of what Mr. Sanders is proposing, while 31 percent opposed it and 25 percent did not take a position. Views of the Affordable Care Act are split right down the middle, with 50 percent approving of it and 48 percent disapproving of it in an April poll by Gallup.

Given the Democratic advantage, many Republicans say they should not focus their energy on health care but instead emphasize immigration and other issues where they are stronger. But the president and his team counter that even if they cannot win on health care, it would be ridiculous to simply cede the territory if they could at least narrow the gap.

The president feels compelled to have something specific to counter Medicare for all. Still, people close to Mr. Trump suggested that if he did release something within a month or two, it might not be a comprehensive plan but a series of smaller proposals that would potentially help, such as ideas for bringing down prescription drug costs, for giving states more flexibility on Medicaid expansion and for promoting more access in the marketplace.

Among those who are said to be influencing the discussion within the administration are Alex M. Azar II, the secretary of health and human services; Seema Verma, the head of the agency that runs Medicare and Medicaid; and Joe Grogan, the director of the White House Domestic Policy Council.

“The president has repeatedly promised something better than the A.C.A. but has never come up with a plan himself, and the congressional plans he endorsed were definitely not better for everyone,” said Larry Levitt, a senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“There’s always a tension for presidents around whether to submit a specific proposal to Congress or let the legislative process play out,” Mr. Levitt added. “When it comes to health care, the challenge has been that the president has not only avoided proposing a specific plan, but has made promises that no plan could ever fulfill.”

Mr. Trump often laments the failure by blaming Senator John McCain, Republican of Arizona, who voted against one repeal effort in the summer of 2017. Even if Mr. McCain had voted for the bill, however, full repeal of the Affordable Care Act would not have been assured.

That version would have eliminated the individual and employers’ mandate, but left intact the health care law’s Medicaid expansion and insurance regulations. And it would still have required passage in the House or forced lawmakers from both chambers to negotiate their differences.

When Mr. Trump pushed the idea of voting to repeal the law again recently, he was quickly dissuaded by Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the majority leader, who argued that comprehensive health care legislation would go nowhere in Congress. The president then insisted it was never his intention to vote on a bill before the 2020 election.Even as Mr. Trump has delayed producing a plan, he has continued to criticize the existing health care law, repeatedly claiming that it had become unaffordable because of average deductibles exceeding $7,000 or $8,000. This was an exaggeration.

Deductibles vary greatly by the type of plan and the enrollee. While deductibles for some plans can top $7,000, they average $4,375 for silver-tier plans, the most common choice for consumers. And those who receive cost-sharing reductions have lower deductibles still. Also left unsaid was his own administration’s role in causing higher deductibles, as the federal government sets caps on out-of-pocket costs and has increased the limit this year.

Midway through his third year in office, many remain skeptical that Mr. Trump will produce the plan he is now promising to unveil in a month or two.

“He can’t deliver the impossible,” said Len M. Nichols, the director of the Center for Health Policy Research and Ethics at George Mason University, “so he avoids specifics and postpones actually reckoning with a serious legislative proposal of his own.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/16/us/politics/trump-health-care-democrats-2020.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

Trump Officials Broaden Attack on Health Law, Arguing Courts Should Reject All of It

by Robert Pear - March 25, 2019

WASHINGTON

— The Trump administration broadened its attack on the Affordable Care

Act on Monday, telling a federal appeals court that it now believed the

entire law should be invalidated.

The administration had previously said that the law’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions should be struck down, but that the rest of the law, including the expansion of Medicaid, should survive.

If the appeals court accepts the Trump administration’s new arguments, millions of people could lose health insurance, including those who gained coverage through the expansion of Medicaid and those who have private coverage subsidized by the federal government.

“The Justice Department is no longer asking for partial invalidation of the Affordable Care Act, but says the whole law should be struck down,” Abbe R. Gluck, a law professor at Yale who has closely followed the litigation, said on Monday. “Not just some of the insurance provisions, but all of it, including the Medicaid expansion and hundreds of other reforms. That’s a total bombshell, which could have dire consequences for millions of people.”

The administration had previously said that the law’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions should be struck down, but that the rest of the law, including the expansion of Medicaid, should survive.

If the appeals court accepts the Trump administration’s new arguments, millions of people could lose health insurance, including those who gained coverage through the expansion of Medicaid and those who have private coverage subsidized by the federal government.

“The Justice Department is no longer asking for partial invalidation of the Affordable Care Act, but says the whole law should be struck down,” Abbe R. Gluck, a law professor at Yale who has closely followed the litigation, said on Monday. “Not just some of the insurance provisions, but all of it, including the Medicaid expansion and hundreds of other reforms. That’s a total bombshell, which could have dire consequences for millions of people.”

The new position is

also certain to reignite a political furor over the Affordable Care

Act, ensuring that it will figure even more prominently in the 2020

elections. Democrats have been saying that President Trump still wants

to abolish the law, and they can now point to the Justice Department’s

filing as evidence to support that contention.

[What happens if Obamacare is struck down? Read more.]

The Justice Department disclosed its new stance in a two-sentence letter to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in New Orleans, and will elaborate on its position in a brief to be filed later.

In the letter, the Justice Department said the court should affirm a judgment issued in December by Judge Reed O’Connor of the Federal District Court in Fort Worth.

Judge O’Connor, in a sweeping opinion, said that the individual mandate requiring people to have health insurance “can no longer be sustained as an exercise of Congress’s tax power” because Congress had eliminated the tax penalty for people who go without health insurance.

Accordingly, Judge O’Connor said, “the individual mandate is unconstitutional” and the remaining provisions of the Affordable Care Act are also invalid.

[What happens if Obamacare is struck down? Read more.]

The Justice Department disclosed its new stance in a two-sentence letter to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in New Orleans, and will elaborate on its position in a brief to be filed later.

In the letter, the Justice Department said the court should affirm a judgment issued in December by Judge Reed O’Connor of the Federal District Court in Fort Worth.

Judge O’Connor, in a sweeping opinion, said that the individual mandate requiring people to have health insurance “can no longer be sustained as an exercise of Congress’s tax power” because Congress had eliminated the tax penalty for people who go without health insurance.

Accordingly, Judge O’Connor said, “the individual mandate is unconstitutional” and the remaining provisions of the Affordable Care Act are also invalid.

In

its letter to the appeals court, the Justice Department said on Monday

that it “is not urging that any portion of the district court’s judgment

be reversed.” In other words, it agrees with Judge O’Connor’s ruling.

In the nine years since it was signed by President Barack Obama, the Affordable Care Act has become embedded in the nation’s health care system. It changed the way Medicare pays doctors, hospitals and other health care providers. It has unleashed a tidal wave of innovation in the delivery of health care. The health insurance industry has invented a new business model selling coverage to anyone who applies, regardless of any pre-existing conditions.

The law also includes dozens of provisions that are less well known and not related to the individual mandate. It requires nutrition labeling and calorie counts on menu items at chain restaurants. It requires certain employers to provide “reasonable break time” and a private space for nursing mothers to pump breast milk. It improved prescription drug coverage for Medicare beneficiaries, and it created a new pathway for the approval of less expensive versions of biologic medicines made from living cells.

Lawyers said invalidation of the entire law would raise numerous legal and practical questions. It is, they said, difficult to imagine what the health care world would look like without the Affordable Care Act.

The Trump administration’s new position was harshly criticized by the insurance industry and by consumer advocates.

The government’s position “puts coverage at risk for more than 100 million Americans,” said Matt Eyles, the president and chief executive of America’s Health Insurance Plans.

Leslie Dach, the chairman of Protect Our Care, a consumer advocacy group, said: “In November, voters overwhelmingly rejected President Trump’s health care repeal and sabotage agenda. But he remains dead set on accomplishing through the courts what he and his allies in Congress could not do legislatively: fully repeal the law, devastate American health care and leave millions of Americans at risk.”

In the nine years since it was signed by President Barack Obama, the Affordable Care Act has become embedded in the nation’s health care system. It changed the way Medicare pays doctors, hospitals and other health care providers. It has unleashed a tidal wave of innovation in the delivery of health care. The health insurance industry has invented a new business model selling coverage to anyone who applies, regardless of any pre-existing conditions.

The law also includes dozens of provisions that are less well known and not related to the individual mandate. It requires nutrition labeling and calorie counts on menu items at chain restaurants. It requires certain employers to provide “reasonable break time” and a private space for nursing mothers to pump breast milk. It improved prescription drug coverage for Medicare beneficiaries, and it created a new pathway for the approval of less expensive versions of biologic medicines made from living cells.

Lawyers said invalidation of the entire law would raise numerous legal and practical questions. It is, they said, difficult to imagine what the health care world would look like without the Affordable Care Act.

The Trump administration’s new position was harshly criticized by the insurance industry and by consumer advocates.

The government’s position “puts coverage at risk for more than 100 million Americans,” said Matt Eyles, the president and chief executive of America’s Health Insurance Plans.

Leslie Dach, the chairman of Protect Our Care, a consumer advocacy group, said: “In November, voters overwhelmingly rejected President Trump’s health care repeal and sabotage agenda. But he remains dead set on accomplishing through the courts what he and his allies in Congress could not do legislatively: fully repeal the law, devastate American health care and leave millions of Americans at risk.”

The Trump

administration’s new stance appears to put Republicans in Congress in an

awkward position. They have repeatedly tried to repeal the health law.

But in the last year, they said over and over that they wanted to

protect coverage for people with pre-existing conditions, and those

protections are among the law’s most popular provisions.

The lawsuit challenging the Affordable Care Act, Texas v. United States, was filed last year by a group of Republican governors and state attorneys general. Officials from California and more than a dozen other states have intervened to defend the law.

The Texas lawsuit “is as dangerous as it is reckless,” Xavier Becerra, the attorney general of California, said on Monday as he filed a brief urging the appeals court to uphold the law.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/25/us/politics/obamacare-unconstitutional-trump-aca.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

The lawsuit challenging the Affordable Care Act, Texas v. United States, was filed last year by a group of Republican governors and state attorneys general. Officials from California and more than a dozen other states have intervened to defend the law.

The Texas lawsuit “is as dangerous as it is reckless,” Xavier Becerra, the attorney general of California, said on Monday as he filed a brief urging the appeals court to uphold the law.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/25/us/politics/obamacare-unconstitutional-trump-aca.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

On the Doorstep With a Plea: Will You Support Medicare for All?

by Abby Goodnough - NYT - June 15, 2019

DUBUQUE, Iowa — Art Miller listened patiently as the stranger on his doorstep tried to sell him on the Medicare for All Act of 2019, the single-payer health care bill that has sharply divided Democrats in Congress and on the presidential campaign trail.

The visitor, Steven Meier, was a volunteer canvasser who wanted Mr. Miller to call his congresswoman, Abby Finkenauer, the young Democrat who took a Republican’s seat last year in this closely divided district — and press her to embrace Medicare for all. Beyond congressional politics, there was the familiar role that Iowa plays as the first state to weigh in on the fight for the Democratic presidential nomination.

“I want to know how my grandkids are going to pay for it, O.K.?” Mr. Miller, 71, mused, peering at the flier that Mr. Meier had handed him.

It was a fairly typical encounter for Mr. Meier, 39, who with hundreds of volunteers around the country is working with National Nurses United, the country’s largest nurses’ union, to build grass-roots support for the single-payer bill, a long shot on Capitol Hill and a disruptive force in the party. House Democrats have declared this Saturday and Sunday to be “a weekend of action on health care” — but they are split over whether to embrace extreme change or something closer to the status quo.

The visitor, Steven Meier, was a volunteer canvasser who wanted Mr. Miller to call his congresswoman, Abby Finkenauer, the young Democrat who took a Republican’s seat last year in this closely divided district — and press her to embrace Medicare for all. Beyond congressional politics, there was the familiar role that Iowa plays as the first state to weigh in on the fight for the Democratic presidential nomination.

“I want to know how my grandkids are going to pay for it, O.K.?” Mr. Miller, 71, mused, peering at the flier that Mr. Meier had handed him.

It was a fairly typical encounter for Mr. Meier, 39, who with hundreds of volunteers around the country is working with National Nurses United, the country’s largest nurses’ union, to build grass-roots support for the single-payer bill, a long shot on Capitol Hill and a disruptive force in the party. House Democrats have declared this Saturday and Sunday to be “a weekend of action on health care” — but they are split over whether to embrace extreme change or something closer to the status quo.

A single-payer health care system

would more or less scrap private health insurance, including

employer-sponsored coverage, for a system like Canada’s in which the

government pays for everyone’s health care with tax dollars. Democrats

not ready for that big a step are falling back on a “public option,” an

alternative in which anyone could buy into Medicare or another public

program, or stick with private insurance — a position once a considered

firmly on the party’s left wing.

Lawmakers like Ms. Finkenauer, mindful of the delicate political balance in their districts, fear the “socialism” epithet that President Trump and his party are attaching to Medicare for all. On Friday, Mr. Trump called the House bill “socialist health care” that would “crush American workers with higher taxes, long wait times and far worse care.” But even Ms. Finkenauer, who beat the incumbent Republican in November by 16,900 votes, has been pulled left by the debate, embracing the public option, which could not get through Congress when the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010.

Lawmakers like Ms. Finkenauer, mindful of the delicate political balance in their districts, fear the “socialism” epithet that President Trump and his party are attaching to Medicare for all. On Friday, Mr. Trump called the House bill “socialist health care” that would “crush American workers with higher taxes, long wait times and far worse care.” But even Ms. Finkenauer, who beat the incumbent Republican in November by 16,900 votes, has been pulled left by the debate, embracing the public option, which could not get through Congress when the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010.

Mr.

Meier, along with hundreds of other volunteers around the country, is

working with National Nurses United, the country’s largest nurses’

union, to build grass-roots support for the single-payer bill.CreditLauren Justice for The New York Times

“In a divided Congress, I’m focused on what we can do to bring immediate relief to Iowans,” she said in an email.

The nurses’ union and a number of other progressive groups want nothing less than a government system that pays for everyone’s health care, seizing on the issue’s prominence and a round of Medicare for all hearings in the House with canvassing in the districts of many of the 123 House Democrats who have not thrown their support behind a single-payer system.

The nurses’ union and a number of other progressive groups want nothing less than a government system that pays for everyone’s health care, seizing on the issue’s prominence and a round of Medicare for all hearings in the House with canvassing in the districts of many of the 123 House Democrats who have not thrown their support behind a single-payer system.

“Hearings

are a moment for us to have a national stage for this campaign,”

Jasmine Ruddy, the lead organizer for the nurse union’s Medicare for all

campaign, told several dozen new volunteers on a training call last

month. “It’s up to us to take advantage of the momentum we already see

happening and turn it into political power.”

But building support for a single-payer health care system has been slow going. On Wednesday, the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, Representative Richard E. Neal of Massachusetts, convening the House’s third Medicare for all hearing, said it was about “exploring ideas.”

Republicans warned darkly of sky-high tax increases, doctor shortages and long waits for care. Representative Kevin Brady of Texas, the senior Republican on the committee, said his constituents were “frightened” about their private coverage being “ripped out from under them.”

The nurses’ union campaign began just after Democrats won the House in November, when the union and several other groups held a strategy call with Representative Pramila Jayapal, Democrat of Washington, the chief author of the Medicare for All Act, and Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who pushed Medicare for all into the mainstream during his 2016 presidential campaign.

“Rather than try to convince people it’s the right system,” Ms. Ruddy said, “our strategy is to reach the people who are already convinced that health care is a human right, to bring them in and actually make them feel the action they are taking matters.”

But building support for a single-payer health care system has been slow going. On Wednesday, the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, Representative Richard E. Neal of Massachusetts, convening the House’s third Medicare for all hearing, said it was about “exploring ideas.”

Republicans warned darkly of sky-high tax increases, doctor shortages and long waits for care. Representative Kevin Brady of Texas, the senior Republican on the committee, said his constituents were “frightened” about their private coverage being “ripped out from under them.”

The nurses’ union campaign began just after Democrats won the House in November, when the union and several other groups held a strategy call with Representative Pramila Jayapal, Democrat of Washington, the chief author of the Medicare for All Act, and Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who pushed Medicare for all into the mainstream during his 2016 presidential campaign.

“Rather than try to convince people it’s the right system,” Ms. Ruddy said, “our strategy is to reach the people who are already convinced that health care is a human right, to bring them in and actually make them feel the action they are taking matters.”

Students

from the Rush University Medical Center demonstrated in support of

Medicare for All legislation outside the Blue Cross Blue Shield of

Illinois headquarters in Chicago.CreditJoshua Lott for The New York Times

In

Dubuque, Mr. Meier and his partner, Briana Moss, have knocked on 250

doors and gathered about 50 signatures over the past few months. About

20 volunteers, including a retired nurse and several college students,

are also involved. Nationwide, canvassers have knocked on 20,000 doors

and collected 14,000 signatures since February.

On

a Saturday afternoon, Mr. Miller, a Vietnam veteran, told Mr. Meier

about his positive experience with government health care through the

Department of Veterans Affairs, saying, “I’ve seen how it can work.”

A few houses down, a woman who owns a cleaning service and would give only her first name, Sharon, and her party affiliation, Republican, said that if the bill covered abortions, “I won’t go for that.”

She added that she would be happy to stop paying $170 a month for supplemental insurance to cover what Medicare does not, but she did not want to see people who do not work receive free care. From the garage, her husband hollered that he agreed. Conceding defeat, Mr. Meier and Ms. Moss moved along.

Both Sanders supporters, they took on the cause in part because Ms. Moss has Type 1 diabetes and has struggled on and off to stay insured, though now she has Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of the program. Ms. Moss, 30, went to see Ms. Finkenauer in her district office this year and asked if she supported a government system that eliminated insurance. Ms. Finkenauer, she said, stated her preference for a public option.

“That’s simply a compromise that leaves the insurance companies still in the game,” said Mr. Meier, who recently started working at John Deere building backhoes and will soon have employer-based coverage after being uninsured for his entire adult life.

The Jayapal and Sanders bills would both expand traditional Medicare to cover all Americans, and change the structure of the program to cover more services and eliminate most deductibles and co-payments. There would effectively be no private health insurance, because the new system would cover almost everything; Mr. Sanders has said private coverage could be sold for extras like cosmetic surgery.

A few houses down, a woman who owns a cleaning service and would give only her first name, Sharon, and her party affiliation, Republican, said that if the bill covered abortions, “I won’t go for that.”

She added that she would be happy to stop paying $170 a month for supplemental insurance to cover what Medicare does not, but she did not want to see people who do not work receive free care. From the garage, her husband hollered that he agreed. Conceding defeat, Mr. Meier and Ms. Moss moved along.

Both Sanders supporters, they took on the cause in part because Ms. Moss has Type 1 diabetes and has struggled on and off to stay insured, though now she has Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of the program. Ms. Moss, 30, went to see Ms. Finkenauer in her district office this year and asked if she supported a government system that eliminated insurance. Ms. Finkenauer, she said, stated her preference for a public option.

“That’s simply a compromise that leaves the insurance companies still in the game,” said Mr. Meier, who recently started working at John Deere building backhoes and will soon have employer-based coverage after being uninsured for his entire adult life.

The Jayapal and Sanders bills would both expand traditional Medicare to cover all Americans, and change the structure of the program to cover more services and eliminate most deductibles and co-payments. There would effectively be no private health insurance, because the new system would cover almost everything; Mr. Sanders has said private coverage could be sold for extras like cosmetic surgery.

Mr.

Meier and Ms. Moss have knocked on 250 doors and gathered about 50

signatures over the last few months. About 20 other volunteers,

including a retired nurse and several college students, are also

involved.

While polling does show

that Medicare for all has broad public support, that drops once people

learn it would involve raising taxes or eliminating private insurance.

That finding bewilders Mr. Meier, given many of the conversations he has

on people’s front steps.

Those conversations keep

coming. Rick Plowman 66, complained bitterly about how despite having

Medicare, he had to pay nearly $500 for inhalers to treat his chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Still, he was skeptical.

“I just don’t know what it’s going to look like down the road,” Mr. Plowman said. “Even Social Security for kids, you know? Even for you guys?”

“I’m willing to start making that sacrifice right now,” Mr. Meier pushed back. Mr. Plowman signed the petition.

At a white bungalow around the corner, Mr. Meier found — finally — that he was preaching to the choir with Bobby Daniels, 50, and his wife, Andrea, 46. Mr. Daniels, a forklift operator from Waterloo, said their coverage came with a $3,000 deductible and he would “most definitely” support Medicare for all. Ray Edwards, 36, an uninsured barber, also heartily signed on.

At the final stop of the day, Mr. Meier and Ms. Moss encountered Jeremy Shade, 36, a registered Republican who promptly told them his sister lived in Canada and had spent “hours and hours in the hospital, waiting for care” under that country’s single-payer system.

“I get that concern, and it’s something I’m worried about, too,” Mr. Meier said as Mr. Shade’s dog barked. “Would you be interested in maybe just calling Abby Finkenauer and saying, ‘Hey, what are we doing about the health care problem in this country?’”

“My wife would,” Mr. Shade said, explaining that she was a Democrat. “I’m real wary about it.”

Two hours of hot canvassing amid swarms of gnats had yielded six petition signatures and a few pledges to call Ms. Finkenauer. Mr. Meier was determined to end on a positive note. “I really think health care could be the issue that could get people to stop being so on one side or the other,” he said, a point that Mr. Shade accepted, shaking his hand before retreating inside.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/15/us/politics/medicare-for-all-democrats.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

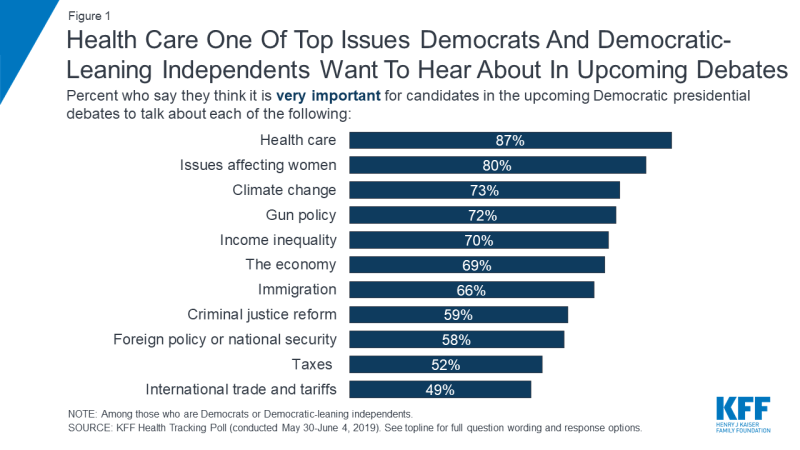

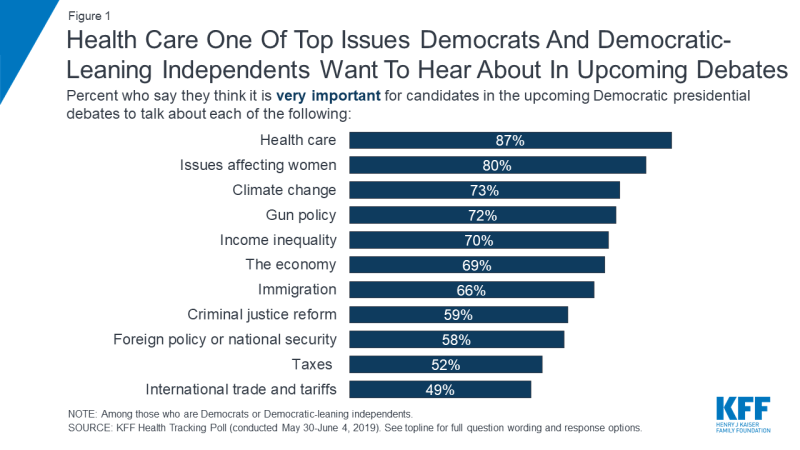

About seven in ten say it is “very important” for the candidates to

discuss climate change (73 percent), gun policy (72 percent), income

inequality (70 percent), the economy (69 percent), and immigration (66

percent). These are followed by criminal justice reform (59 percent),

foreign policy or national security (58 percent), and about half say it

is “very important” for the candidates to talk about taxes (52 percent)

and international trade and tariffs (49 percent) in the upcoming

Democratic debates.

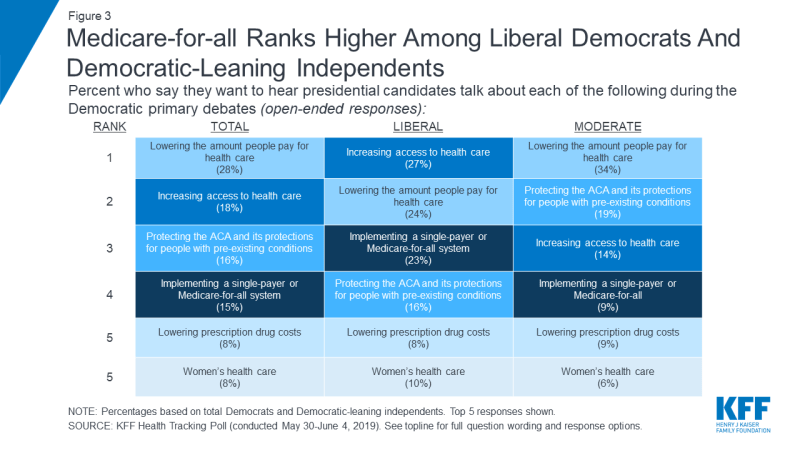

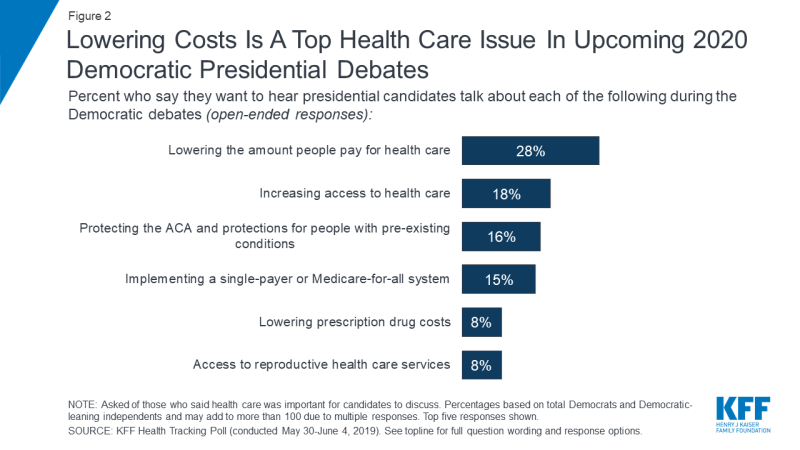

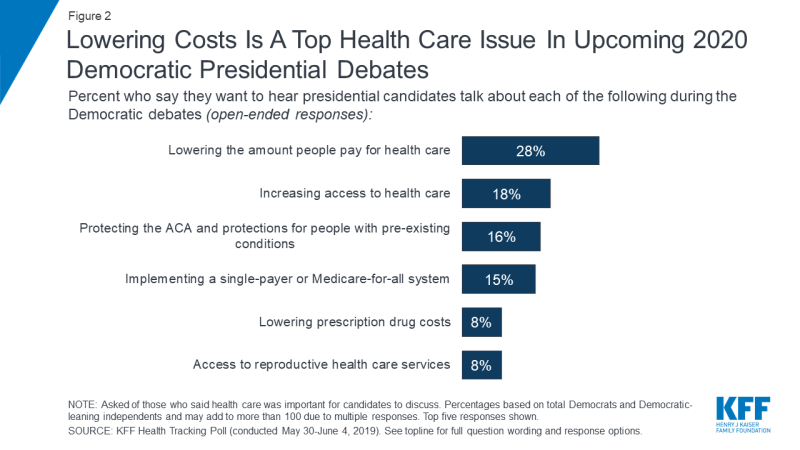

When those who say health care is at least somewhat important for 2020 Democratic presidential candidates to discuss in upcoming debates are asked to offer in their own words what specifically about health care they want to hear about, nearly three in ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents overall offer responses related to lowering the amount people pay for health care (28 percent) and another eight percent explicitly mention lowering prescription drug costs. To learn more about Americans’ experiences with health care costs, check out this data note.

Access to health care also emerges as a key issue with one in five (18 percent) offering responses related to increasing access to health care and an additional 15 percent explicitly mentioning implementing a single-payer or Medicare-for-all system. The 2010 Affordable Care Act is also still on the minds of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents with one in six mentioning protecting the Affordable Care Act and protections for people with pre-existing conditions (16 percent) as the top health care issue they want to hear about during the upcoming presidential debates. An additional one in ten (8 percent) offer access to reproductive health care services.

Though lowering costs and increasing access emerge as the top issues

that Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents want to hear

presidential candidates talk about, there are some notable differences

between liberals and moderates. One-fourth of liberal Democrats and

Democratic-leaning independents (23 percent) offer implementing a

single-payer or Medicare-for-all system when asked what health care

issue they want to hear the candidates discuss, making it among the top

health care issues offered by this group along with increasing access

(27 percent) and lowering the amount people pay for health care (24

percent). Among moderate Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents,

more than three times as many offer lowering the amount people pay for

health care (34 percent) than implementing a Medicare-for-all system (9

percent).

Kaiser Family Foundation Focus Groups

During the spring of 2019, Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a series of 6 focus groups with a total of 56 participants in Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania, examining voters’ top health care issues and their views of various national health care proposals. The groups included Republicans, Democrats, independents, seniors, and young adults, and found a disconnect between what the public is talking about when it comes to health care compared to the political discussions happening in Washington, D.C. and on the 2020 campaign trail. Read Drew Altman’s takeaways from the KFF focus groups here.

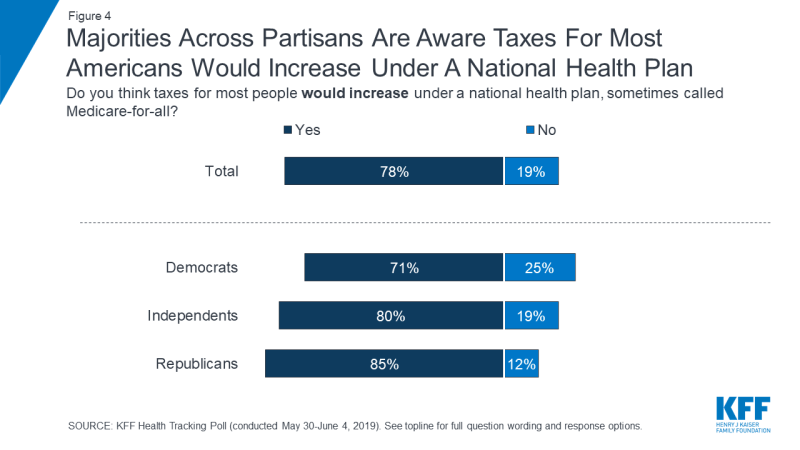

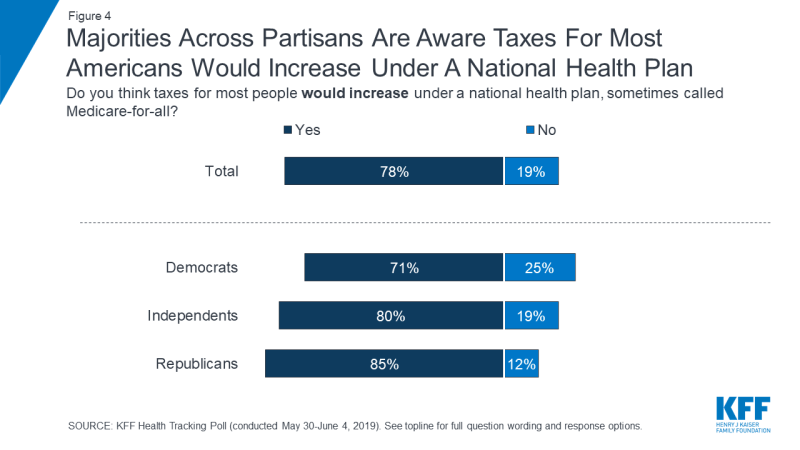

Eight in ten (78 percent) think that under a national health plan, sometimes called Medicare-for-all, taxes for most people would increase. Majorities of Democrats (71 percent), independents (80 percent), and Republicans (85 percent) say that taxes for most Americans would increase under a national health plan.

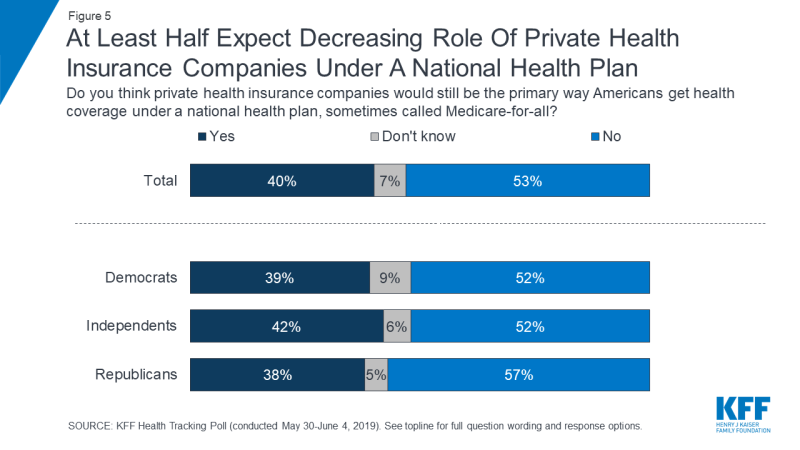

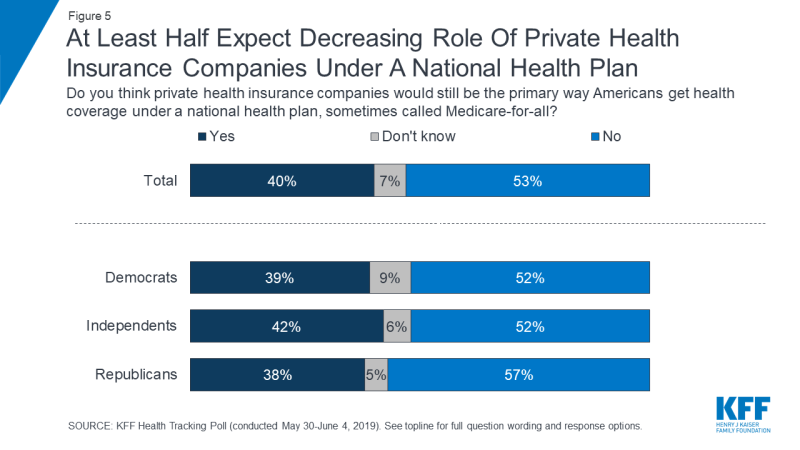

In addition, about half of Americans (53 percent) – including half of

Democrats and independents (52 percent each) and most Republicans (57

percent) – think that under a national health plan, private health

insurances would no longer be the primary way Americans would get health

coverage. Still, a substantial four in ten of the public believe that

under such a plan, private health insurance companies would still be the

primary source of coverage for most Americans and an additional seven

percent say they do not know what would happen under a national health

plan.

In focus groups, many participants expressed skepticism about the

idea that private insurance companies would cease to exist under a

Medicare-for-all plan. Some thought these companies were just too

powerful, and others thought they would continue to exist for people who

want to buy extra coverage beyond what a national plan would offer.

Focus group findings also indicate that many people don’t believe a

Medicare-for-all plan would result in the elimination of health

insurance premiums or cost-sharing.

Methodology

California is beefing up Obamacare, restoring an individual mandate, expanding health insurance subsidies well into the middle class and covering some undocumented adults through Medicaid. It’s an incremental step toward universal coverage that can animate the Democrats’ party-defining debate over how best to cover everyone — through a mixed public-private system or through “Medicare for All."

The Democratic-controlled state legislature on Thursday approved a budget, clearing the path for a statewide penalty for failing to purchase health insurance, which will help subsidize coverage for middle-income people earning too much to receive federal financial help from Obamacare. California will also become the first state to extend Medicaid coverage to low-income undocumented adults up to age 26, defying the Trump administration’s efforts to shrink government benefits to immigrants.

Story Continued Below

The moves fall well short of a sweeping Medicare for All-style system vigorously supported by the party’s progressive wing here in California and across the country — and viewed much more cautiously by much of the Democratic establishment.

The idea of expanding Obamacare subsidies could gain traction among more moderate Democrats in Washington who would rather build on the Affordable Care Act than engage in another protracted health reform battle should the party take back control in Washington. And they can sell it as a practical move toward expanding coverage immediately while the party weighs more progressive health plans.

“I view California as a model state that’s likely to be used as a best practices example for how Congress can move ahead in a new Democratic administration without in any way creating barriers to do more aggressive policies in the future,” said Chris Jennings, who was a health policy adviser in the Clinton and Obama administrations.

Case in point: California’s new progressive governor, Gavin Newsom, said he remains committed to setting up a single-payer system in the state, but he made the Obamacare expansion and coverage for undocumented immigrants a priority his first year.

Peter Lee, executive director of Covered California, the state's Obamacare marketplace, said the legislature’s coverage expansion was an indication “we can’t stand still” while others debate more sweeping overhauls of the health care system.

California's plan isn’t a done deal. Having cleared the $215 billion budget, state lawmakers in the coming days must pass a series of bills approving the health measures through an expedited process.

House Democratic leaders in Washington, wary of a pursuing a fully government-run single-payer system, have embraced a key element of the California plan. They unveiled a package this spring that would vastly expand eligibility for health insurance subsidies, though it didn't include reviving Obamacare's requirement to purchase coverage.

The proposed California mandate largely mirrors the federal penalty that was eliminated by Congress in late 2017. But California's mandate would be pegged to the state's income tax filing threshold, which is higher than the federal level, meaning more people would be exempt from the penalty.

The mandate penalty, along with $450 million from the state's general fund over the next three years, helps pay for the expanded subsidies. The penalty is expected to generate an estimated $295 million this coming fiscal year, and as much as $380 million in 2022.

Under Obamacare, health insurance subsidies are cut off for people earning above four times the federal poverty level, or about $50,000 for an individual. California is extending subsidies to those earning six times the poverty level, or about $75,000 for an individual. About 190,000 Californians would be eligible for those expanded subsidies.

Even if the individual mandate is eventually approved as expected, some observers say it could face challenges in the courts — and possibly come at a political price. Opponents of the idea have criticized California for restoring the unpopular individual mandate while also extending Medicaid coverage to about 90,000 undocumented immigrants.

Story Continued Below

“How, for Pete’s sake, do you impose an individual mandate on contributing taxpayers who are citizens of California and subsidize undocumented immigrants by giving them free health care?” said Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association in California. “There’s an equity issue here that’s going to be part of the political miss.”

California is covering most of the cost of Medicaid coverage for young undocumented adults, estimated at $98 million this year. Still, the state is planning to draw some federal funds for this group, which could spark pushback from the Trump administration.

Coupal said the way the Legislature is advancing the mandate makes it ripe for a legal challenge. He said it amounts to a new tax, meaning it should go through regular legislative order instead of the fast-track budget process.

David McCuan, a California political analyst, said the state's health proposals "mark California as a barometer of where health care can go,” but he also expects to see “numerous” legal challenges, particularly over the mandate.

Several health experts pointed out that a handful of states have passed individual mandates since Congress gutted Obamacare's — including New Jersey, Vermont and Washington, D.C — and none have been challenged in court. Rhode Island lawmakers are also considering mandate legislation this year. Massachusetts was the first state to pass an individual mandate in 2006, and it became the model for the Affordable Care Act.

https://www.politico.com/story/2019/06/16/california-obamacare-health-care-1530461?

“I just don’t know what it’s going to look like down the road,” Mr. Plowman said. “Even Social Security for kids, you know? Even for you guys?”

“I’m willing to start making that sacrifice right now,” Mr. Meier pushed back. Mr. Plowman signed the petition.

At a white bungalow around the corner, Mr. Meier found — finally — that he was preaching to the choir with Bobby Daniels, 50, and his wife, Andrea, 46. Mr. Daniels, a forklift operator from Waterloo, said their coverage came with a $3,000 deductible and he would “most definitely” support Medicare for all. Ray Edwards, 36, an uninsured barber, also heartily signed on.

At the final stop of the day, Mr. Meier and Ms. Moss encountered Jeremy Shade, 36, a registered Republican who promptly told them his sister lived in Canada and had spent “hours and hours in the hospital, waiting for care” under that country’s single-payer system.

“I get that concern, and it’s something I’m worried about, too,” Mr. Meier said as Mr. Shade’s dog barked. “Would you be interested in maybe just calling Abby Finkenauer and saying, ‘Hey, what are we doing about the health care problem in this country?’”

“My wife would,” Mr. Shade said, explaining that she was a Democrat. “I’m real wary about it.”

Two hours of hot canvassing amid swarms of gnats had yielded six petition signatures and a few pledges to call Ms. Finkenauer. Mr. Meier was determined to end on a positive note. “I really think health care could be the issue that could get people to stop being so on one side or the other,” he said, a point that Mr. Shade accepted, shaking his hand before retreating inside.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/15/us/politics/medicare-for-all-democrats.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

KFF Health Tracking Poll – June 2019: Health Care in the Democratic Primary and Medicare-for-all - Findings

Kaiser Family Foundation - June 2019

Key Findings:

- Health care is leading the list of possible topics Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents want to hear the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates talk about during their upcoming debates, with nearly nine in ten (87 percent) saying it is very important for candidates to talk about health care. This is closely followed by eight in ten who say it is very important for candidates to discuss issues affecting women, perhaps reflecting recent news attention on these issues. Health care and women’s issues rank ahead of other top issues for Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents such as climate change (73 percent), gun policy (72 percent), income inequality (70 percent), the economy (69 percent), and immigration (66 percent).

- When asked to say in their own words which health care issues they

want to hear candidates discuss, affordability emerges as a top issue

with nearly three in ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents

mentioning lowering the amount people pay for health care (28 percent). A further eight percent mention lowering the cost of prescription drugs. Access to health care also emerges as a key topic with one in five mentioning increasing access to health care (18 percent) while an additional 15 percent explicitly mention implementing a single-payer or Medicare-for-all system.

Poll: Most Americans don’t realize how dramatically the leading Medicare-for-all proposals would restructure the nation’s health care system

- The most recent KFF Health Tracking Poll finds majorities across partisans think taxes for most people would increase under a national health plan, sometimes called Medicare-for-all (78 percent), and about half (53 percent) think private health insurance companies would no longer be the primary way Americans would get health coverage under such a plan. However, when it comes to other key changes that the leading Medicare-for-all bills introduced by Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Pramila Jayapal would bring, large shares are unaware of how the current health care system may be affected. For example, majorities say people would continue to pay deductibles and co-pays (69 percent) and continue to pay premiums (54 percent) under a Medicare-for-all plan. Likewise, majorities say people with employer-sponsored or self-purchased insurance would be able to keep their plans (55 percent each) under a Medicare-for-all plan.

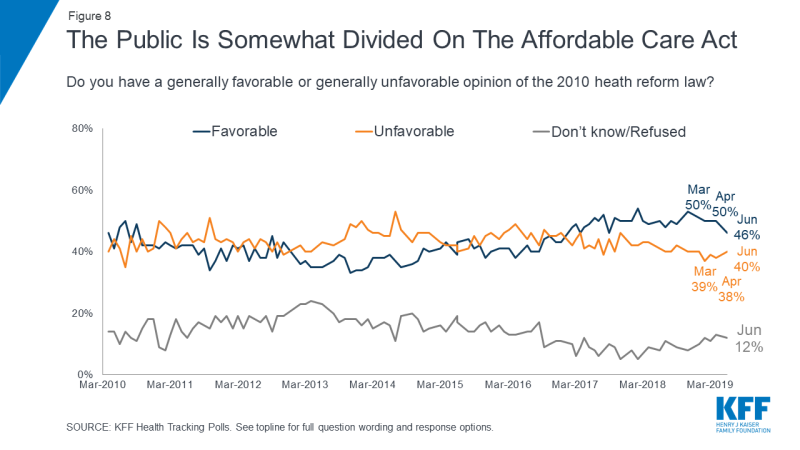

- Overall, nearly half of the public (46 percent) hold favorable views of the 2010 Affordable Care Act while four in ten hold unfavorable views. Majorities of Democrats continue to hold favorable views towards the law while majorities of Republicans hold unfavorable views. Independents are more divided with similar shares holding favorable and unfavorable views. To see the shifts in public attitudes towards the law over time, check out the KFF interactive.

Health Care in The Democratic Primary

What do Democrats want their 2020 presidential candidates to talk about heading into the primary debates? Health care and issues affecting women top their priority list in this @KaiserFamFound pollLess than one month before the first 2020 Democratic presidential primary debate, KFF polling finds health care is among the top issues that Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents want to hear the candidates talk about during the upcoming debates. Nearly nine in ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (87 percent) say it is “very important” for the candidates to talk about health care during the upcoming Democratic presidential debates. This is followed by eight in ten who say it is “very important” for the candidates to discuss issues that affect women, an issue that garnered recent media attention.

Figure 1: Health Care One Of Top Issues Democrats And Democratic-Leaning Independents Want To Hear About In Upcoming Debates

When those who say health care is at least somewhat important for 2020 Democratic presidential candidates to discuss in upcoming debates are asked to offer in their own words what specifically about health care they want to hear about, nearly three in ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents overall offer responses related to lowering the amount people pay for health care (28 percent) and another eight percent explicitly mention lowering prescription drug costs. To learn more about Americans’ experiences with health care costs, check out this data note.

Access to health care also emerges as a key issue with one in five (18 percent) offering responses related to increasing access to health care and an additional 15 percent explicitly mentioning implementing a single-payer or Medicare-for-all system. The 2010 Affordable Care Act is also still on the minds of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents with one in six mentioning protecting the Affordable Care Act and protections for people with pre-existing conditions (16 percent) as the top health care issue they want to hear about during the upcoming presidential debates. An additional one in ten (8 percent) offer access to reproductive health care services.

Figure 2: Lowering Costs Is A Top Health Care Issue In Upcoming 2020 Democratic Presidential Debates

Kaiser Family Foundation Focus Groups

During the spring of 2019, Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a series of 6 focus groups with a total of 56 participants in Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania, examining voters’ top health care issues and their views of various national health care proposals. The groups included Republicans, Democrats, independents, seniors, and young adults, and found a disconnect between what the public is talking about when it comes to health care compared to the political discussions happening in Washington, D.C. and on the 2020 campaign trail. Read Drew Altman’s takeaways from the KFF focus groups here.

A National Health Plan or Medicare-for-all

Implementing a national health plan, sometimes called Medicare-for-all, has been a dominant issue during the 2020 Democratic primary. Previous KFF polling has found that a slight majority supports the idea of a national health plan, but attitudes towards such a proposal are fairly malleable with significant shares, on either side of the debate, shifting their opinion once they hear counter-arguments. With several bills being introduced in the 116th Congress that would expand the role of public programs in health, this month’s Kaiser Health Tracking Poll examines the public’s awareness on key aspects of Medicare-for-all plans including Sen. Sanders’ Medicare for All Act of 2019 and Rep. Japayal’s bill of the same name.1Eight in ten (78 percent) think that under a national health plan, sometimes called Medicare-for-all, taxes for most people would increase. Majorities of Democrats (71 percent), independents (80 percent), and Republicans (85 percent) say that taxes for most Americans would increase under a national health plan.

Figure 4: Majorities Across Partisans Are Aware Taxes For Most Americans Would Increase Under A National Health Plan

Figure 5: At Least Half Expect Decreasing Role Of Private Health Insurance Companies Under A National Health Plan

In their own words: Focus group participants on private insurance

[Moderator: Do you think Medicare-for-all means that private health insurance companies will go away?]

“No, because they’d be running Medicare-for-all.” (Houston, independent)

“Or even those individuals who can afford to have the type of coverage they want, they wouldn’t want a basic burger. No, they want to add all of the extra fixings because they can afford it.” (Houston, independent)

“They’re going to take a hit obviously but I don’t think that they’re really going to go away. They’re too powerful.” (Harrisburg, Democrat)

“I don’t think for a second that private insurance would go away, even if you implemented this. There will always be the Cadillac plan that is available, because as long as somebody—the market will react.” (Orlando, Democrat)

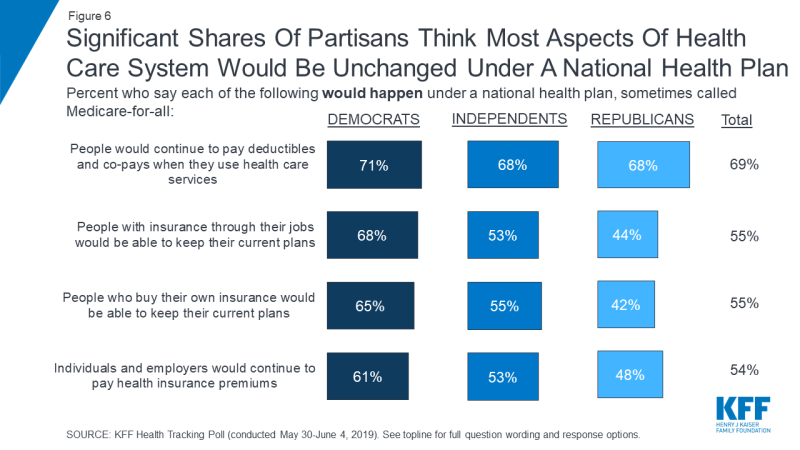

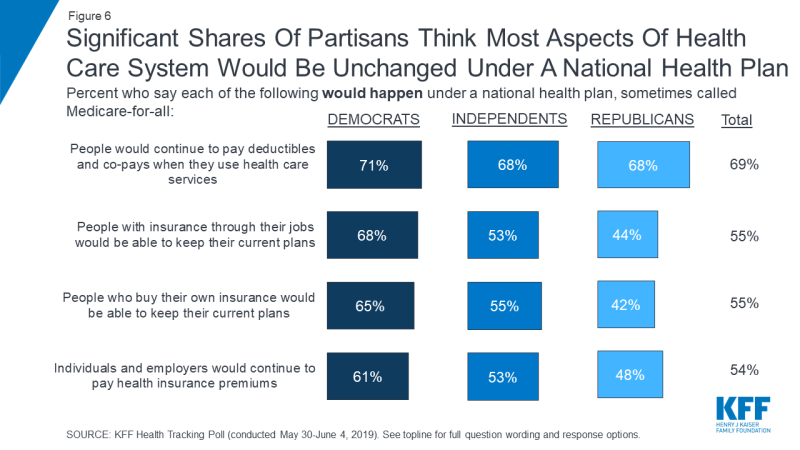

When it comes to other potential impacts of a national health plan,

many Americans say most aspects of the current health care system would

remain unchanged. Majorities of Democrats, independents, and Republicans

say people would continue to pay deductibles and co-pays when they use

health care services (71 percent, 68 percent, and 68 percent,

respectively). In addition, majorities of both Democrats and

independents also believe people with employer-sponsored insurance would

be able to keep their current coverage (68 percent and 53 percent),

people who purchase their own plans would be able to keep their current

coverage (65 percent and 55 percent), and individuals and employers

would continue to pay health insurance premiums (61 percent and 53

percent). At least four in ten Republicans also say each of these things

would happen under a national health plan. Small shares of the public

overall say they don’t know whether each of these things would happen

under such a plan (4 percent say they don’t know if people would

continue to pay deductibles and co-pays, 7 percent say they don’t know

for the other changes included).[Moderator: Do you think Medicare-for-all means that private health insurance companies will go away?]

“No, because they’d be running Medicare-for-all.” (Houston, independent)

“Or even those individuals who can afford to have the type of coverage they want, they wouldn’t want a basic burger. No, they want to add all of the extra fixings because they can afford it.” (Houston, independent)

“They’re going to take a hit obviously but I don’t think that they’re really going to go away. They’re too powerful.” (Harrisburg, Democrat)

“I don’t think for a second that private insurance would go away, even if you implemented this. There will always be the Cadillac plan that is available, because as long as somebody—the market will react.” (Orlando, Democrat)

Figure

6: Significant Shares Of Partisans Think Most Aspects Of Health Care

System Would Be Unchanged Under A National Health Plan

In their own words: Focus group participants on premiums and cost-sharing

[Moderator: Do you think Medicare-for-all means that there would be no more co-pays or deductibles when people use care?]

“No, I think there’d probably still be co-pays and deductibles, but just be affordable.” (Houston, independent)

“It wouldn’t make sense to you that you wouldn’t have to pay [co-pays and deductibles] because it wouldn’t feel sustainable.” (Houston, independent)

“My mom is on Medicare and she has to pay co-pays.” (Houston, independent)

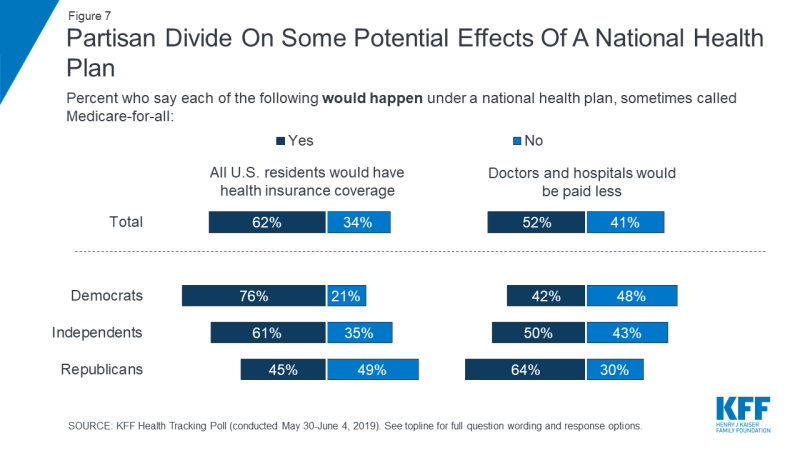

There is a partisan divide on some aspects of how a national health

plan would affect people and health care providers. Three-fourths of

Democrats (76 percent) say that all U.S. residents would have health

insurance coverage under a national health plan while about half of

Republicans say this would not happen (49 percent). On

the other hand, most Republicans say a national health plan would lead

to doctors and hospitals being paid less (64 percent) while about half

of Democrats say this would not happen (48 percent).

Large shares of independents believe both of these things would happen,

with six in ten (61 percent) saying all U.S. residents would get health

coverage and half saying doctors and hospitals would be paid less.[Moderator: Do you think Medicare-for-all means that there would be no more co-pays or deductibles when people use care?]

“No, I think there’d probably still be co-pays and deductibles, but just be affordable.” (Houston, independent)

“It wouldn’t make sense to you that you wouldn’t have to pay [co-pays and deductibles] because it wouldn’t feel sustainable.” (Houston, independent)

“My mom is on Medicare and she has to pay co-pays.” (Houston, independent)

| Table 1: Partisans Disagree On Some Basic Implications of a National Health Plan | ||||

| Percent who think each of the following would happen under a national plan, sometimes called Medicare-for-all: | Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| Taxes for most people would increase | 78% | 71% | 80% | 85% |

| All U.S. residents would have health insurance coverage | 62 | 76 | 61 | 45 |

| Private health insurance companies would NOT be the primary way Americans get health coverage | 53 | 52 | 52 | 57 |

| Doctors and hospitals would be paid less | 52 | 42 | 50 | 64 |

| People who buy their own insurance would NOT be able to keep their current plans | 39 | 24 | 40 | 53 |

| Individuals and employers would NOT continue to pay health insurance premiums | 39 | 31 | 42 | 45 |

| People with employer-sponsored insurance would NOT be able to keep their current plans | 38 | 25 | 42 | 47 |

| People would NOT continue to pay deductibles and co-pays when they use health care services | 27 | 25 | 29 | 28 |

Public Views of The ACA

While the public still holds largely partisan views over the Affordable Care Act and opinions have remained relatively unchanged for the past two years since the Republican efforts to repeal the law, views are down slightly this month. Nearly half of the public (46 percent) hold favorable opinions of the ACA while four in ten hold a negative opinion of the law. Across partisans, nearly eight in ten Democrats (79 percent) have a favorable view of the ACA compared to nearly half of independents (47 percent), and about one-sixth of Republicans (16 percent).Methodology

California goes even bigger on Obamacare

by Victoria Colliver - Politico - June 18, 20190

The state is advancing a sweeping health care package that could shape Democrats' debate over universal coverage.California is beefing up Obamacare, restoring an individual mandate, expanding health insurance subsidies well into the middle class and covering some undocumented adults through Medicaid. It’s an incremental step toward universal coverage that can animate the Democrats’ party-defining debate over how best to cover everyone — through a mixed public-private system or through “Medicare for All."

The Democratic-controlled state legislature on Thursday approved a budget, clearing the path for a statewide penalty for failing to purchase health insurance, which will help subsidize coverage for middle-income people earning too much to receive federal financial help from Obamacare. California will also become the first state to extend Medicaid coverage to low-income undocumented adults up to age 26, defying the Trump administration’s efforts to shrink government benefits to immigrants.

Story Continued Below

The moves fall well short of a sweeping Medicare for All-style system vigorously supported by the party’s progressive wing here in California and across the country — and viewed much more cautiously by much of the Democratic establishment.

The idea of expanding Obamacare subsidies could gain traction among more moderate Democrats in Washington who would rather build on the Affordable Care Act than engage in another protracted health reform battle should the party take back control in Washington. And they can sell it as a practical move toward expanding coverage immediately while the party weighs more progressive health plans.

“I view California as a model state that’s likely to be used as a best practices example for how Congress can move ahead in a new Democratic administration without in any way creating barriers to do more aggressive policies in the future,” said Chris Jennings, who was a health policy adviser in the Clinton and Obama administrations.

Case in point: California’s new progressive governor, Gavin Newsom, said he remains committed to setting up a single-payer system in the state, but he made the Obamacare expansion and coverage for undocumented immigrants a priority his first year.

Peter Lee, executive director of Covered California, the state's Obamacare marketplace, said the legislature’s coverage expansion was an indication “we can’t stand still” while others debate more sweeping overhauls of the health care system.

California's plan isn’t a done deal. Having cleared the $215 billion budget, state lawmakers in the coming days must pass a series of bills approving the health measures through an expedited process.

House Democratic leaders in Washington, wary of a pursuing a fully government-run single-payer system, have embraced a key element of the California plan. They unveiled a package this spring that would vastly expand eligibility for health insurance subsidies, though it didn't include reviving Obamacare's requirement to purchase coverage.

The proposed California mandate largely mirrors the federal penalty that was eliminated by Congress in late 2017. But California's mandate would be pegged to the state's income tax filing threshold, which is higher than the federal level, meaning more people would be exempt from the penalty.

The mandate penalty, along with $450 million from the state's general fund over the next three years, helps pay for the expanded subsidies. The penalty is expected to generate an estimated $295 million this coming fiscal year, and as much as $380 million in 2022.

Under Obamacare, health insurance subsidies are cut off for people earning above four times the federal poverty level, or about $50,000 for an individual. California is extending subsidies to those earning six times the poverty level, or about $75,000 for an individual. About 190,000 Californians would be eligible for those expanded subsidies.

Even if the individual mandate is eventually approved as expected, some observers say it could face challenges in the courts — and possibly come at a political price. Opponents of the idea have criticized California for restoring the unpopular individual mandate while also extending Medicaid coverage to about 90,000 undocumented immigrants.

Story Continued Below

“How, for Pete’s sake, do you impose an individual mandate on contributing taxpayers who are citizens of California and subsidize undocumented immigrants by giving them free health care?” said Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association in California. “There’s an equity issue here that’s going to be part of the political miss.”

California is covering most of the cost of Medicaid coverage for young undocumented adults, estimated at $98 million this year. Still, the state is planning to draw some federal funds for this group, which could spark pushback from the Trump administration.

Coupal said the way the Legislature is advancing the mandate makes it ripe for a legal challenge. He said it amounts to a new tax, meaning it should go through regular legislative order instead of the fast-track budget process.

David McCuan, a California political analyst, said the state's health proposals "mark California as a barometer of where health care can go,” but he also expects to see “numerous” legal challenges, particularly over the mandate.

Several health experts pointed out that a handful of states have passed individual mandates since Congress gutted Obamacare's — including New Jersey, Vermont and Washington, D.C — and none have been challenged in court. Rhode Island lawmakers are also considering mandate legislation this year. Massachusetts was the first state to pass an individual mandate in 2006, and it became the model for the Affordable Care Act.

https://www.politico.com/story/2019/06/16/california-obamacare-health-care-1530461?

Florida Company Sued Over Sales of Skimpy Health Plans

by Reed Abelson - NYT - June 12, 2019

One Ohio

resident paid $240 a month for health insurance that she later learned

didn’t cover her knee replacement. Saddled with $48,000 in medical

bills, she decided not to get the other knee replaced.

“It’s been devastating to me,” said Elizabeth Belin, who lives in Columbus. The bills totaled more than her annual salary.

A Kansas resident paid premiums on a policy for two years, then found out his insurance would not cover surgery for a newly diagnosed cancer.

The two policyholders have filed a lawsuit in federal court against Health Insurance Innovations, based in Tampa, Fla., accusing the company of misleading them about the kind of policy they were buying.

“It’s been devastating to me,” said Elizabeth Belin, who lives in Columbus. The bills totaled more than her annual salary.

A Kansas resident paid premiums on a policy for two years, then found out his insurance would not cover surgery for a newly diagnosed cancer.

The two policyholders have filed a lawsuit in federal court against Health Insurance Innovations, based in Tampa, Fla., accusing the company of misleading them about the kind of policy they were buying.

They

say they believed they were purchasing Affordable Care Act plans that

include coverage guarantees. But they were sold much less comprehensive

coverage that left them vulnerable to tens of thousands of dollars in

unpaid medical bills, according to the lawsuit.

Their complaints underscore problems with some types of cheaper health insurance alternatives that the Trump administration has expanded. Critics of the government’s decision, including the Association for Community Affiliated Plans and the National Alliance on Mental Illness, are also suing the Trump administration over relaxation of rules for these plans.

“This isn’t real insurance,” said Jason Kellogg, one of the lawyers representing the individuals in the Florida case. They are seeking class-action status, estimating that as many as 500,000 people may have bought these policies.

In an emailed statement, Health Insurance Innovations said the lawsuit was without merit. “We will vigorously defend ourselves against all such allegations,” the company said.

Proponents of short-term plans say they represent an affordable option for those who can’t pay for the robust coverage mandated by the federal law.

Their complaints underscore problems with some types of cheaper health insurance alternatives that the Trump administration has expanded. Critics of the government’s decision, including the Association for Community Affiliated Plans and the National Alliance on Mental Illness, are also suing the Trump administration over relaxation of rules for these plans.

“This isn’t real insurance,” said Jason Kellogg, one of the lawyers representing the individuals in the Florida case. They are seeking class-action status, estimating that as many as 500,000 people may have bought these policies.