Single-Payer Health Care in the United States

Steffie Woolhandler, MD and David U. Himmelstein, MD - Journal of the American Medical Association - May 31, 2019

The prospect of single-payer “Medicare-for-all” reform

evokes enthusiasm and concern. Proponents maintain that a single-payer

system would be the simplest route to universal coverage; every US

resident would qualify for comprehensive insurance under a public,

tax-financed plan that would replace private insurers, Medicaid, and

Medicare. Others are concerned that costs would escalate or that the

government would limit and underfund care, particularly hospital care,

which commands the largest share of health spending; innovation might

lag; and government may infringe on medical decisions.

Physicians are understandably cautious about prescribing a radical cure for minor ills. However, current health policies have substantial shortcomings for many individuals, minor changes appear certain to fail, and the single-payer remedy may be less disruptive than often portrayed.

Few argue with the need for reform. The United States has fallen behind other nations in measures of life expectancy and access to care. Drug prices in the United States, already twice those in Europe, continue to increase, compromising patient adherence to vital medications, such as insulin. Twenty-nine million US residents remain uninsured, and co-payments and deductibles force many individuals with insurance to choose between skipping care and incurring overwhelming debts.

Many physicians feel frustrated by mandates and restrictions of insurers and by electronic health records (EHRs) with designs driven by the logic of billing. New payment modalities, euphemistically labeled “value-based,” favor large systems at the expense of small practices and community-controlled hospitals and impose new layers of quality reporting and fiscal managers. However, these payment modalities appear to have done little to improve care or moderate costs, and physicians continue to bear responsibility for patients even as their authority in many health care settings erodes.

Single-payer reform could mitigate the stresses on patients and clinicians. A well-designed reform could potentially generate large savings on billing-related costs and lower drug prices, which would make expanded coverage more affordable.

The current, fragmented payment system entails complexity that adds no value. Physicians and hospitals must navigate contracting and credentialing with multiple plans and contend with numerous payment rates and restrictions, preauthorization requirements, quality metrics, and formularies. Narrow clinician and hospital networks and the constant flux of enrollment/disenrollment as patients change jobs or their employers switch plans disrupt long-standing patient-physician relationships. Many insurers devote resources to recruiting profitable enrollees and encouraging unprofitable enrollees to disenroll.

This complexity drains resources from patient care. According to official estimates, insurance overhead is projected to cost an estimated $301.4 billion in 2019, including an estimated $252 billion for private insurers, approximately 12% of their premiums.1 In contrast, overhead is 1.6% in Canada's single-payer system and 2.2% in Medicare’s fee-for-service plan. Reducing US systemwide insurance overhead to 2.2% could save an estimated $238.7 billion.1

The complex payment system also increases hospital costs and prices. Single-payer nations, such as Canada and Scotland, pay hospitals global budgets, analogous to the way US cities fund fire departments. That payment strategy obviates the need to attribute costs to individual patients and insurers and minimizes incentives for upcoding, gaming quality metrics, bolstering profitable “service lines,” and other financially driven exertions; a 1272-bed multihospital system in Toronto employs only 5.5 full-time equivalent employees to handle all billing and collections.2 A 2014 report suggested that administration consumes 12.4% of hospital budgets in Canada (and 11.6% in Scotland) vs 25.3% in the United States,3 a difference of an estimated $162 billion annually.

Interacting with multiple insurers also raises physicians’ overhead and, in turn, the prices they must charge. In 2016, an efficient group practice at a North Carolina academic medical center spent $99 581 (and 243 hours of physician time) per primary care physician on billing.4

As in Canada, a US single-payer system could pay physicians based on a simple fee schedule negotiated with medical associations. All patients would have the same coverage and office staff would not need to process prior authorizations, collect co-payments, or field pharmacists' calls driven by the confusion that arises from multiple formularies. Anecdotal reports suggest that Canadian physicians have been spared much of the burden imposed by poorly conceived privacy regulations, “meaningful use” requirements, and quality and efficiency metrics.2 A 2011 study found that US physicians spent 4 times more money interacting with payers than their Canadian counterparts,5 who report spending only 24.7% of gross revenues on practice overhead (including rent and staff) and 4% of their workweek on insurance-related matters.6 US insurers try to detect billing abuses by demanding substantial amounts of documentation. In single-payer nations, the sole insurer can use comprehensive claims data to monitor for outlandish billing patterns.

A 2019 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report7 concluded that single-payer reform could lower administrative costs, increase incentives to improve health, and substantially reduce the number of uninsured individuals. However, if undocumented immigrants were excluded, 11 million US residents could remain uninsured.

Realizing the benefits of single-payer reform entails many challenges and potential pitfalls. As the CBO report noted, the effects on the economy and individuals would depend on key features of the design of the program, such as how it paid clinicians and what services were covered. While single-payer reform could simplify bureaucracy and free up hospital resources and physicians' time to meet the increased demand for care, poorly designed legislation might perpetuate Medicare's burdensome payment and monitoring strategies. Even in a well-designed system, waiting time for care might increase; however, the Affordable Care Act, which covered 20 million uninsured individuals, did not significantly increase waiting time or compromise access for previously insured individuals. Nonetheless, enhanced funding for training programs might be needed to ensure an adequate supply of clinicians, particularly in primary and behavioral health care and in regions with physician shortages. In addition, as with Medicare, politics could affect decisions regarding coverage in a single-payer system.

Most individuals would have an insurance transition, but they could keep their physicians and would be spared future transitions. Although patients would not be able to choose among insurers, they would no longer face network restrictions and, in many cases, could have improved benefits. To protect innovation, some drug price savings could be used to augment federal research funding.

Single-payer reform would be best done at the federal level. Without federal waivers, state-based reforms cannot redirect federal and employer spending through the single-payer system, compromising the administrative savings needed to make expanded care affordable—a problem that bedeviled Vermont's reform effort.

Consolidation of purchasing power in a public agency may raise concerns that funding reductions would endanger quality or cause rationing, and that physicians would essentially become tradesperson paid by a single entity. Schulman et al calculated that hospitals’ average margins would decline to −9% if all inpatient stays were reimbursed at Medicare's current rates.8 While hospitals’ savings on their own administrative costs (as much as $162 billion) could allow them to transition to a leaner cost structure, a sensible phase-in plan would be needed. Although neither of the congressional Medicare-for-all bills calls for the adoption of Medicare's rates, their budgeting is predicated on the assumption that hospitals could redirect resources from billing to clinical sites, allowing them to provide more care within current budgets.

Previous experience with coverage expansions is also reassuring. In Canada, mean physician income (in 2010 inflation-adjusted Canadian dollars) increased from about $100 000 in 1962 to $248 113 in 2010 (from 2.5 times the average worker's income to 4.3 times),9 which was comparable to US physician income at the time. Similarly, hospital revenue per patient-day increased 8.9% annually in the 3 years after the 1959 startup of Canada's universal hospital insurance program.10 The implementation of Medicare in 1966, the closest US analogue of a single-payer startup, also was associated with increased physician and hospital revenues.

State and federal legislators have introduced dozens of single-payer bills. Sixteen US senators and 110 representatives are cosponsoring companion Medicare-for-all bills that would implement universal, first-dollar coverage without network restrictions. Both federal bills would raise taxes, but those increases are projected to be fully offset by savings on premiums and out-of-pocket expenses. Both bills would augment funding for clinical services by redirecting funds now wasted on bureaucracy and excessive drug prices and the payer would pay physicians on a fee-for-service basis or salaries from hospitals or clinics that receive global budgets. The bill in the US House of Representatives adopts Canadian-style global budgeting for hospitals. However, the current US Senate bill retains Medicare's payment strategies (although not Medicare's payment rates), a provision that would modestly attenuate savings on hospital administration and maintain some unnecessary regulations that frustrate physicians. This shortcoming underscores the importance of physician input in crafting single-payer legislation.

Several legislators have introduced public-option (Medicare buy-in) proposals, portraying these proposals as more practical variants of Medicare for all. However, such reform would do little to simplify billing and paying, generating minimal administrative savings for clinicians or hospitals. Savings on insurance overhead would also be modest unless Medicare Advantage (in which overhead averages 13.7%) was excluded. Moreover, private insurers might selectively enroll healthy patients, turning the public option into a de facto high-risk pool requiring large subsidies. Hence, as the CBO report noted, expanded coverage would be costlier than under single-payer reform.

Halfway measures are politically attractive but economically unworkable. The $11 559 per capita that the United States spends on health care could provide high-quality care for all or it can continue to fund a vast health-managerial apparatus—it cannot do both.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2735406

Many Want ‘Medicare for All.’Physicians are understandably cautious about prescribing a radical cure for minor ills. However, current health policies have substantial shortcomings for many individuals, minor changes appear certain to fail, and the single-payer remedy may be less disruptive than often portrayed.

Few argue with the need for reform. The United States has fallen behind other nations in measures of life expectancy and access to care. Drug prices in the United States, already twice those in Europe, continue to increase, compromising patient adherence to vital medications, such as insulin. Twenty-nine million US residents remain uninsured, and co-payments and deductibles force many individuals with insurance to choose between skipping care and incurring overwhelming debts.

Many physicians feel frustrated by mandates and restrictions of insurers and by electronic health records (EHRs) with designs driven by the logic of billing. New payment modalities, euphemistically labeled “value-based,” favor large systems at the expense of small practices and community-controlled hospitals and impose new layers of quality reporting and fiscal managers. However, these payment modalities appear to have done little to improve care or moderate costs, and physicians continue to bear responsibility for patients even as their authority in many health care settings erodes.

Single-payer reform could mitigate the stresses on patients and clinicians. A well-designed reform could potentially generate large savings on billing-related costs and lower drug prices, which would make expanded coverage more affordable.

The current, fragmented payment system entails complexity that adds no value. Physicians and hospitals must navigate contracting and credentialing with multiple plans and contend with numerous payment rates and restrictions, preauthorization requirements, quality metrics, and formularies. Narrow clinician and hospital networks and the constant flux of enrollment/disenrollment as patients change jobs or their employers switch plans disrupt long-standing patient-physician relationships. Many insurers devote resources to recruiting profitable enrollees and encouraging unprofitable enrollees to disenroll.

This complexity drains resources from patient care. According to official estimates, insurance overhead is projected to cost an estimated $301.4 billion in 2019, including an estimated $252 billion for private insurers, approximately 12% of their premiums.1 In contrast, overhead is 1.6% in Canada's single-payer system and 2.2% in Medicare’s fee-for-service plan. Reducing US systemwide insurance overhead to 2.2% could save an estimated $238.7 billion.1

The complex payment system also increases hospital costs and prices. Single-payer nations, such as Canada and Scotland, pay hospitals global budgets, analogous to the way US cities fund fire departments. That payment strategy obviates the need to attribute costs to individual patients and insurers and minimizes incentives for upcoding, gaming quality metrics, bolstering profitable “service lines,” and other financially driven exertions; a 1272-bed multihospital system in Toronto employs only 5.5 full-time equivalent employees to handle all billing and collections.2 A 2014 report suggested that administration consumes 12.4% of hospital budgets in Canada (and 11.6% in Scotland) vs 25.3% in the United States,3 a difference of an estimated $162 billion annually.

Interacting with multiple insurers also raises physicians’ overhead and, in turn, the prices they must charge. In 2016, an efficient group practice at a North Carolina academic medical center spent $99 581 (and 243 hours of physician time) per primary care physician on billing.4

As in Canada, a US single-payer system could pay physicians based on a simple fee schedule negotiated with medical associations. All patients would have the same coverage and office staff would not need to process prior authorizations, collect co-payments, or field pharmacists' calls driven by the confusion that arises from multiple formularies. Anecdotal reports suggest that Canadian physicians have been spared much of the burden imposed by poorly conceived privacy regulations, “meaningful use” requirements, and quality and efficiency metrics.2 A 2011 study found that US physicians spent 4 times more money interacting with payers than their Canadian counterparts,5 who report spending only 24.7% of gross revenues on practice overhead (including rent and staff) and 4% of their workweek on insurance-related matters.6 US insurers try to detect billing abuses by demanding substantial amounts of documentation. In single-payer nations, the sole insurer can use comprehensive claims data to monitor for outlandish billing patterns.

A 2019 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report7 concluded that single-payer reform could lower administrative costs, increase incentives to improve health, and substantially reduce the number of uninsured individuals. However, if undocumented immigrants were excluded, 11 million US residents could remain uninsured.

Realizing the benefits of single-payer reform entails many challenges and potential pitfalls. As the CBO report noted, the effects on the economy and individuals would depend on key features of the design of the program, such as how it paid clinicians and what services were covered. While single-payer reform could simplify bureaucracy and free up hospital resources and physicians' time to meet the increased demand for care, poorly designed legislation might perpetuate Medicare's burdensome payment and monitoring strategies. Even in a well-designed system, waiting time for care might increase; however, the Affordable Care Act, which covered 20 million uninsured individuals, did not significantly increase waiting time or compromise access for previously insured individuals. Nonetheless, enhanced funding for training programs might be needed to ensure an adequate supply of clinicians, particularly in primary and behavioral health care and in regions with physician shortages. In addition, as with Medicare, politics could affect decisions regarding coverage in a single-payer system.

Most individuals would have an insurance transition, but they could keep their physicians and would be spared future transitions. Although patients would not be able to choose among insurers, they would no longer face network restrictions and, in many cases, could have improved benefits. To protect innovation, some drug price savings could be used to augment federal research funding.

Single-payer reform would be best done at the federal level. Without federal waivers, state-based reforms cannot redirect federal and employer spending through the single-payer system, compromising the administrative savings needed to make expanded care affordable—a problem that bedeviled Vermont's reform effort.

Consolidation of purchasing power in a public agency may raise concerns that funding reductions would endanger quality or cause rationing, and that physicians would essentially become tradesperson paid by a single entity. Schulman et al calculated that hospitals’ average margins would decline to −9% if all inpatient stays were reimbursed at Medicare's current rates.8 While hospitals’ savings on their own administrative costs (as much as $162 billion) could allow them to transition to a leaner cost structure, a sensible phase-in plan would be needed. Although neither of the congressional Medicare-for-all bills calls for the adoption of Medicare's rates, their budgeting is predicated on the assumption that hospitals could redirect resources from billing to clinical sites, allowing them to provide more care within current budgets.

Previous experience with coverage expansions is also reassuring. In Canada, mean physician income (in 2010 inflation-adjusted Canadian dollars) increased from about $100 000 in 1962 to $248 113 in 2010 (from 2.5 times the average worker's income to 4.3 times),9 which was comparable to US physician income at the time. Similarly, hospital revenue per patient-day increased 8.9% annually in the 3 years after the 1959 startup of Canada's universal hospital insurance program.10 The implementation of Medicare in 1966, the closest US analogue of a single-payer startup, also was associated with increased physician and hospital revenues.

State and federal legislators have introduced dozens of single-payer bills. Sixteen US senators and 110 representatives are cosponsoring companion Medicare-for-all bills that would implement universal, first-dollar coverage without network restrictions. Both federal bills would raise taxes, but those increases are projected to be fully offset by savings on premiums and out-of-pocket expenses. Both bills would augment funding for clinical services by redirecting funds now wasted on bureaucracy and excessive drug prices and the payer would pay physicians on a fee-for-service basis or salaries from hospitals or clinics that receive global budgets. The bill in the US House of Representatives adopts Canadian-style global budgeting for hospitals. However, the current US Senate bill retains Medicare's payment strategies (although not Medicare's payment rates), a provision that would modestly attenuate savings on hospital administration and maintain some unnecessary regulations that frustrate physicians. This shortcoming underscores the importance of physician input in crafting single-payer legislation.

Several legislators have introduced public-option (Medicare buy-in) proposals, portraying these proposals as more practical variants of Medicare for all. However, such reform would do little to simplify billing and paying, generating minimal administrative savings for clinicians or hospitals. Savings on insurance overhead would also be modest unless Medicare Advantage (in which overhead averages 13.7%) was excluded. Moreover, private insurers might selectively enroll healthy patients, turning the public option into a de facto high-risk pool requiring large subsidies. Hence, as the CBO report noted, expanded coverage would be costlier than under single-payer reform.

Halfway measures are politically attractive but economically unworkable. The $11 559 per capita that the United States spends on health care could provide high-quality care for all or it can continue to fund a vast health-managerial apparatus—it cannot do both.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2735406

Statement of Peter S. Arno, PhD

Senior Fellow and Director Health Policy Research Political Economy Research Institute University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Senior Fellow and Director Health Policy Research Political Economy Research Institute University of Massachusetts, Amherst

before the

Joint Legislative Hearing Universal Single-Payer Health Coverage New York State Legislature

Joint Legislative Hearing Universal Single-Payer Health Coverage New York State Legislature

Albany, New York

May 28, 2019

Evidence from around the world demonstrates that publicly financed universal health care

systems result in improved health outcomes, lower costs, and greater equity.

A single payer framework as embodied in the New York Health Act (NYHA) is far superior to other reform proposals currently being touted by politicians, pundits and others.

There are two main reasons to pursue real healthcare reform:

These so called reform proposals will not lead to universal coverage nor will they restrain the costs. So why go down this road? Is it too complicated to overhaul our dysfunctional healthcare system when we know that every other developed country in the world has done it?

We often hear a refrain by politicians then regurgitated in the media and vested industry interests: “Why should we blow up the entire health care system with only five percent of the population uninsured, let’s just figure out a way to cover the five percent?” First of all, we are talking about 1.2 million people in the State of New York. Second, it’s not really 5%, particularly if we are talking about adults before they reach Medicare age at 65, when nearly everyone is covered—the uninsured rate is more like 8% for those between the age of 19 and 64—and that number is still close to a million in NY. Third, as we all know the system does not work very well and costs seem to be rising out of control.

But I would like to emphasize something else, a critical issue that is too often glossed over in these discussions. Insurance coverage is not equivalent to access to care. The Commonwealth Fund in their biennial insurance surveys measures what is known as the “Underinsured.”1 These are folks who are covered by health insurance for the entire year, but due to the high costs of copays and deductibles do not access the medical care they need. Their latest survey reveals that in 2016, 10 million New Yorkers between the age of 19 and 64 or 27 percent of this population, who were fully insured for the year, were also underinsured.2 If you add together the uninsured

A single payer framework as embodied in the New York Health Act (NYHA) is far superior to other reform proposals currently being touted by politicians, pundits and others.

There are two main reasons to pursue real healthcare reform:

-

1) To provide universal healthcare coverage

-

2) Rein in the relentless rise in healthcare costs

These so called reform proposals will not lead to universal coverage nor will they restrain the costs. So why go down this road? Is it too complicated to overhaul our dysfunctional healthcare system when we know that every other developed country in the world has done it?

We often hear a refrain by politicians then regurgitated in the media and vested industry interests: “Why should we blow up the entire health care system with only five percent of the population uninsured, let’s just figure out a way to cover the five percent?” First of all, we are talking about 1.2 million people in the State of New York. Second, it’s not really 5%, particularly if we are talking about adults before they reach Medicare age at 65, when nearly everyone is covered—the uninsured rate is more like 8% for those between the age of 19 and 64—and that number is still close to a million in NY. Third, as we all know the system does not work very well and costs seem to be rising out of control.

But I would like to emphasize something else, a critical issue that is too often glossed over in these discussions. Insurance coverage is not equivalent to access to care. The Commonwealth Fund in their biennial insurance surveys measures what is known as the “Underinsured.”1 These are folks who are covered by health insurance for the entire year, but due to the high costs of copays and deductibles do not access the medical care they need. Their latest survey reveals that in 2016, 10 million New Yorkers between the age of 19 and 64 or 27 percent of this population, who were fully insured for the year, were also underinsured.2 If you add together the uninsured

2

and the underinsured, we are now talking about more than a third of New York adults, who have

inadequate access to healthcare, not five percent!

This is one major reason why need a single payer universal system in NY and for the country. This framework as proposed in the NYHA would provide coverage and access to everyone. It is also a reason why most of the other pseudo-reform ideas such as a Medicare buy-in or Medicare option are inferior. As long as we leave private commercial insurers in the mix, none of these plans would reduce these out-of-pocket costs.

There is another refrain, making its way into the overheated talking points by Medicare for All opponents: Across the country we have nearly 160 million people with employer-sponsored insurance, they love their insurance and why should they have to switch to something else, they should have a choice.

Aside from the fact that the comprehensive benefits in the NY Health Act and in the national Medicare for All legislation (H. R. 1384 and S. 1129) are far superior to what is offered in the marketplace, there are no premiums, copays or deductibles, which will vastly improve access to needed medical care.

Do people love their health insurance? It is certainly hard to find them among those who need medical care and discover they must confront insurers regarding restrictive provider networks, pre-approvals, denials in coverage and high out-of-pocket costs.

Over the past 30 years we have seen a steady rise in premiums, copays and deductibles, far outstripping both wages and basic inflation. Over the last ten years between 2008 and 2018, premiums for employer-sponsored insurance plans increased 55 percent, twice as fast as workers’ earnings (26 percent). Over the same time period (2008-2018), the average health insurance deductible for covered workers increased by 212 percent.3 Three-quarters of New York workers with employer-sponsored insurance had deductibles; these deductibles in a family plan averaged more than $3,000 in 2017. 4 How can that not lead to problems accessing the medical care they need?

And what about choice? Certainly consumers want choice, but choice of their own provider, not their insurance company. This is the choice increasingly being denied by the private insurance industry’s narrow and restrictive provider networks. Additionally, how often do we have to change our insurers today, which often means changing our providers In 2018, 66.1 million workers across the country separated from their job at some point during the year—either through layoffs, terminations or just switching jobs.5 This labor turnover data leaves little doubt that people with employer-sponsored insurance are losing their insurance constantly, as are their spouses and children. And even if you stay at the same job your insurance often changes—last

This is one major reason why need a single payer universal system in NY and for the country. This framework as proposed in the NYHA would provide coverage and access to everyone. It is also a reason why most of the other pseudo-reform ideas such as a Medicare buy-in or Medicare option are inferior. As long as we leave private commercial insurers in the mix, none of these plans would reduce these out-of-pocket costs.

There is another refrain, making its way into the overheated talking points by Medicare for All opponents: Across the country we have nearly 160 million people with employer-sponsored insurance, they love their insurance and why should they have to switch to something else, they should have a choice.

Aside from the fact that the comprehensive benefits in the NY Health Act and in the national Medicare for All legislation (H. R. 1384 and S. 1129) are far superior to what is offered in the marketplace, there are no premiums, copays or deductibles, which will vastly improve access to needed medical care.

Do people love their health insurance? It is certainly hard to find them among those who need medical care and discover they must confront insurers regarding restrictive provider networks, pre-approvals, denials in coverage and high out-of-pocket costs.

Over the past 30 years we have seen a steady rise in premiums, copays and deductibles, far outstripping both wages and basic inflation. Over the last ten years between 2008 and 2018, premiums for employer-sponsored insurance plans increased 55 percent, twice as fast as workers’ earnings (26 percent). Over the same time period (2008-2018), the average health insurance deductible for covered workers increased by 212 percent.3 Three-quarters of New York workers with employer-sponsored insurance had deductibles; these deductibles in a family plan averaged more than $3,000 in 2017. 4 How can that not lead to problems accessing the medical care they need?

And what about choice? Certainly consumers want choice, but choice of their own provider, not their insurance company. This is the choice increasingly being denied by the private insurance industry’s narrow and restrictive provider networks. Additionally, how often do we have to change our insurers today, which often means changing our providers In 2018, 66.1 million workers across the country separated from their job at some point during the year—either through layoffs, terminations or just switching jobs.5 This labor turnover data leaves little doubt that people with employer-sponsored insurance are losing their insurance constantly, as are their spouses and children. And even if you stay at the same job your insurance often changes—last

3

year 61 percent of firms offering health benefits reported shopping for a new health plan and

among those 25% actually changed insurance carriers. 6

As Americans become increasingly aware and they are, of rising premiums, copays, deductibles and drug prices, narrow provider networks and our access to private insurance markets in constant flux, public support for a single payer universal system is building momentum.

I have plenty to say about insurance and drug companies, but the hospital folks are in the batters box at this hearing. I have no idea what they are going to say, but I am guessing they are going to whine about the NY Health Act, talk about their thin margins and how the NYHA will damage their finances.

First, let’s be clear, hospitals are the largest component of health expenditures consuming one out of every three health care dollars.

Let us recognize that some of the high costs of running our hospitals are baked into the prices they are forced to pay by our dysfunctional multi-payer system, such as the armies of administrative workers needed to process the bills from hundreds of insurance companies or to arrange payment plans or generate bankruptcies for thousands of New Yorkers with no insurance.

One issue you may not hear much about from the industry is a moral one. Is it ethical or in the public interest to pay hospital executives millions of dollars in compensation, when they are derived in large measure from public taxpayer funds to take care of the poor, the disabled and the elderly through the Medicare and Medicaid programs? In New York there were at least 125 hospital executives and the doctors that work there who were each paid $1 million or more in 2016.7 And the top 500 employees received about $420 million dollars in total compensation that year.

Before any hospital representative goes biblical about how the NYHA will undermine their finances, all is not what it appears to be. A recent financial analysis of 31 nationally prominent not-for-profit hospital systems for the first quarter of 2019 is quite revealing.8 It shows that these systems had an average combined operating margin of 5.1 percent, but after including their investment income, their net margin soared to 16.4 percent. Granted many of these systems are outside New York, but still they reveal that large nonprofit hospital systems resemble and act more like Fortune 500 companies instead of the charities in their origin story.

As dramatic as the hospital executive pay scandal is, it really is chump change compared to what the big health insurers pay. And at least hospitals take care of sick people. What do the insurers do exactly? Do they make the system run more efficiently, do they help control prices? In 2018,

As Americans become increasingly aware and they are, of rising premiums, copays, deductibles and drug prices, narrow provider networks and our access to private insurance markets in constant flux, public support for a single payer universal system is building momentum.

I have plenty to say about insurance and drug companies, but the hospital folks are in the batters box at this hearing. I have no idea what they are going to say, but I am guessing they are going to whine about the NY Health Act, talk about their thin margins and how the NYHA will damage their finances.

First, let’s be clear, hospitals are the largest component of health expenditures consuming one out of every three health care dollars.

Let us recognize that some of the high costs of running our hospitals are baked into the prices they are forced to pay by our dysfunctional multi-payer system, such as the armies of administrative workers needed to process the bills from hundreds of insurance companies or to arrange payment plans or generate bankruptcies for thousands of New Yorkers with no insurance.

One issue you may not hear much about from the industry is a moral one. Is it ethical or in the public interest to pay hospital executives millions of dollars in compensation, when they are derived in large measure from public taxpayer funds to take care of the poor, the disabled and the elderly through the Medicare and Medicaid programs? In New York there were at least 125 hospital executives and the doctors that work there who were each paid $1 million or more in 2016.7 And the top 500 employees received about $420 million dollars in total compensation that year.

Before any hospital representative goes biblical about how the NYHA will undermine their finances, all is not what it appears to be. A recent financial analysis of 31 nationally prominent not-for-profit hospital systems for the first quarter of 2019 is quite revealing.8 It shows that these systems had an average combined operating margin of 5.1 percent, but after including their investment income, their net margin soared to 16.4 percent. Granted many of these systems are outside New York, but still they reveal that large nonprofit hospital systems resemble and act more like Fortune 500 companies instead of the charities in their origin story.

As dramatic as the hospital executive pay scandal is, it really is chump change compared to what the big health insurers pay. And at least hospitals take care of sick people. What do the insurers do exactly? Do they make the system run more efficiently, do they help control prices? In 2018,

4

the CEOs of the eight largest insurers were paid between $12.7 and $26 million each, with an

average payout of $18 million dollars.9

Two final hackneyed refrains--a universal health care system will lead to poorer quality of care and it is so expensive we can’t afford it.

These canards are particularly easy to dispel. First, although the U.S. has the most expensive healthcare system in the world, it ranks near the bottom on a variety of health indicators including infant mortality, life expectancy, preventable mortality and others when compared to other developed countries with universal healthcare.10 The U.S. ranks so poorly in large part because so many Americans lack access to health care.

Second, public financing for healthcare is not a matter of raising new money for healthcare, but of reducing total healthcare outlays and distributing payments more equitably and efficiently. Every credible study out there concludes that a single payer universal framework, with all its benefits, would be less costly than the status quo. The only area of disagreement is by how much. Ten-year national savings estimates range from $2 trillion by the Koch-funded Mercatus Center11 to $5 trillion based on our study at the Political Economy Research Institute.12 Even Rand’s study, with its conservative assumptions on reducing administrative waste and lowering drug prices found billions in savings under the NYHA.13

Of course a single payer system rebalances funding away from private insurers and shifts costs to the public sector. But it also reduces total costs including pharmaceutical expenditures and administrative waste as is done in other developed countries, and provides the leverage to rein in runaway healthcare prices.

In conclusion, implementing a unified single-payer system would reduce administrative costs and eliminate individuals’ and employers’ insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs. If combined with public control of drug prices and regulated provider rates, a sensible single-payer financing system as proposed in the NYHA would reduce healthcare costs while guaranteeing access to comprehensive care and financial security to all.

Two final hackneyed refrains--a universal health care system will lead to poorer quality of care and it is so expensive we can’t afford it.

These canards are particularly easy to dispel. First, although the U.S. has the most expensive healthcare system in the world, it ranks near the bottom on a variety of health indicators including infant mortality, life expectancy, preventable mortality and others when compared to other developed countries with universal healthcare.10 The U.S. ranks so poorly in large part because so many Americans lack access to health care.

Second, public financing for healthcare is not a matter of raising new money for healthcare, but of reducing total healthcare outlays and distributing payments more equitably and efficiently. Every credible study out there concludes that a single payer universal framework, with all its benefits, would be less costly than the status quo. The only area of disagreement is by how much. Ten-year national savings estimates range from $2 trillion by the Koch-funded Mercatus Center11 to $5 trillion based on our study at the Political Economy Research Institute.12 Even Rand’s study, with its conservative assumptions on reducing administrative waste and lowering drug prices found billions in savings under the NYHA.13

Of course a single payer system rebalances funding away from private insurers and shifts costs to the public sector. But it also reduces total costs including pharmaceutical expenditures and administrative waste as is done in other developed countries, and provides the leverage to rein in runaway healthcare prices.

In conclusion, implementing a unified single-payer system would reduce administrative costs and eliminate individuals’ and employers’ insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs. If combined with public control of drug prices and regulated provider rates, a sensible single-payer financing system as proposed in the NYHA would reduce healthcare costs while guaranteeing access to comprehensive care and financial security to all.

5

References

1 Collins, S. R., Gunja, M. Z., & Doty, M. M. (2017). How Well Does Insurance Coverage Protect Consumers from Health Care Costs? Issue Brief. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund. http://bit.ly/2zkg7yj

2 The underinsured is defined here as a “Respondent reported experiencing at least one of the following problems in the past 12 months because of cost: did not fill a prescription; did not see a specialist when needed; skipped a recommended test, treatment, or follow-up; or had a medical problem but did not visit doctor or clinic. Data: The Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2016),” Collins et al. 2018, Table 3. A more recent national study found that in 2018, 51 percent of those with employer- sponsored health insurance skipped or postponed needed care or a prescription medication because of the cost. See Kaiser Family Foundation / LA Times Survey Of Adults With Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance. May 2019. http://bit.ly/2wnyp2n

3 Claxton, G., Rae, M., Long, M., Damico, A., “2018 Employer health benefits survey,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Educational Trust. https://kaiserf.am/2O6oSbd

4 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). http://bit.ly/2v1iNP7

5 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary (JOLTS), May 7, 2019. http://bit.ly/2MdfxOu

6 Claxton, G., Rae, M., Long, M., Damico, A., “2018 Employer health benefits survey,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Educational Trust. https://kaiserf.am/2O6oSbd

7 Lohud.com, New York nonprofit hospital pay 2016, NY Databases.com. http://bit.ly/2Wpktni 8 Herman, B. Hospitals are swimming in cash. Axios, May 21, 2019. http://bit.ly/2X0qNP2

9 Minemyer P. What the CEOs of the 8 largest insurers earned in 2018. Fierce Healthcare, April 23, 2019. http://bit.ly/2M9MnQf

10

11 Blahous, Charles (2018). “The Costs of a National Single-Payer Healthcare System” Mercatus Center, George Mason University. http://bit.ly/2vVNlEY

12 Pollin R, Heintz J, Arno PS, Wicks-Lim J. & Ash M. (November 2018). “Economic Analysis of Medicare for All,” Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts-Amherst. http://bit.ly/PERI_Medicare4All

13 Liu JL, White C, Nowak SA, et al. “An Assessment of the New York Health Act.” (August 2018). Rand Corporation. http://bit.ly/2NYFiPI

1 Collins, S. R., Gunja, M. Z., & Doty, M. M. (2017). How Well Does Insurance Coverage Protect Consumers from Health Care Costs? Issue Brief. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund. http://bit.ly/2zkg7yj

2 The underinsured is defined here as a “Respondent reported experiencing at least one of the following problems in the past 12 months because of cost: did not fill a prescription; did not see a specialist when needed; skipped a recommended test, treatment, or follow-up; or had a medical problem but did not visit doctor or clinic. Data: The Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2016),” Collins et al. 2018, Table 3. A more recent national study found that in 2018, 51 percent of those with employer- sponsored health insurance skipped or postponed needed care or a prescription medication because of the cost. See Kaiser Family Foundation / LA Times Survey Of Adults With Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance. May 2019. http://bit.ly/2wnyp2n

3 Claxton, G., Rae, M., Long, M., Damico, A., “2018 Employer health benefits survey,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Educational Trust. https://kaiserf.am/2O6oSbd

4 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). http://bit.ly/2v1iNP7

5 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary (JOLTS), May 7, 2019. http://bit.ly/2MdfxOu

6 Claxton, G., Rae, M., Long, M., Damico, A., “2018 Employer health benefits survey,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Educational Trust. https://kaiserf.am/2O6oSbd

7 Lohud.com, New York nonprofit hospital pay 2016, NY Databases.com. http://bit.ly/2Wpktni 8 Herman, B. Hospitals are swimming in cash. Axios, May 21, 2019. http://bit.ly/2X0qNP2

9 Minemyer P. What the CEOs of the 8 largest insurers earned in 2018. Fierce Healthcare, April 23, 2019. http://bit.ly/2M9MnQf

10

11 Blahous, Charles (2018). “The Costs of a National Single-Payer Healthcare System” Mercatus Center, George Mason University. http://bit.ly/2vVNlEY

12 Pollin R, Heintz J, Arno PS, Wicks-Lim J. & Ash M. (November 2018). “Economic Analysis of Medicare for All,” Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts-Amherst. http://bit.ly/PERI_Medicare4All

13 Liu JL, White C, Nowak SA, et al. “An Assessment of the New York Health Act.” (August 2018). Rand Corporation. http://bit.ly/2NYFiPI

Foster, G., & Whitmore, H. (October 2018).

Foster, G., & Whitmore, H. (October 2018).

and Health Research &

and Health Research &

Schneider, Eric C., Dana O. Sarnak, David Squires, and Arnav Shah. (2017). “Mirror, Mirror 2017:

International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better US Health Care.” Commonwealth

Fund. http://bit.ly/2zVXFS2

Critics say universal health care will penalize providers the most. These nurses are undeterred.

by Jeneen Interlandi - NYT - May 27, 2019

The experiences that have turned the members of National Nurses United, the nation’s largest union for nurses, into vocal advocates for a universal, government-run health care system are numerous and horrific.

Renelsa Caudill, a Washington, D.C.-area cardiac nurse, remembers being forced to pull a cardiac patient out of the CT scanner before the procedure was complete. The woman had suffered a heart attack earlier that year and was having chest pains. The doctor wanted the scan to help him decide if she needed a potentially risky catheterization, but the woman’s insurance, inexplicably, had refused to cover the test.

Melissa Johnson-Camacho, an oncology nurse in Northern California, remembers a mother who had to ration the special bags that were helping to keep her daughter’s lungs clear. The bags were supposed to be changed every day, so that the daughter did not drown in her own fluids, but they cost $550 each.

And Karla Diederich, also from California, remembers saying a final goodbye to her friend and fellow intensive care nurse Nelly Yap in their hospital’s parking lot. Ms. Yap was dying of metastatic cancer. She was scheduled for another round of chemotherapy, but the hospital had changed owners while she was on sick leave and she’d lost her job — and insurance — as a result. “Nelly spent most of her life taking care of other people,” Ms. Diederich says. “And when she needed that care herself, it was not there.”

Renelsa Caudill, a Washington, D.C.-area cardiac nurse, remembers being forced to pull a cardiac patient out of the CT scanner before the procedure was complete. The woman had suffered a heart attack earlier that year and was having chest pains. The doctor wanted the scan to help him decide if she needed a potentially risky catheterization, but the woman’s insurance, inexplicably, had refused to cover the test.

Melissa Johnson-Camacho, an oncology nurse in Northern California, remembers a mother who had to ration the special bags that were helping to keep her daughter’s lungs clear. The bags were supposed to be changed every day, so that the daughter did not drown in her own fluids, but they cost $550 each.

And Karla Diederich, also from California, remembers saying a final goodbye to her friend and fellow intensive care nurse Nelly Yap in their hospital’s parking lot. Ms. Yap was dying of metastatic cancer. She was scheduled for another round of chemotherapy, but the hospital had changed owners while she was on sick leave and she’d lost her job — and insurance — as a result. “Nelly spent most of her life taking care of other people,” Ms. Diederich says. “And when she needed that care herself, it was not there.”

The

women say that their professional experiences have led them to an

inescapable conclusion: The motives of gargantuan for-profit health care

industries — hospitals, pharmaceuticals, insurance — are incompatible

with those of health care itself. They argue that a single-payer system,

run by the federal government and available to all United States

residents regardless of income or employment status, is the only way to

fully eliminate the obstacles that routinely prevent doctors and nurses

from doing their jobs.

Several proposals now working their way through Congress would aim to create just such a system. The nurses’ support for such proposals — the union has endorsed a bill put forth by Representative Pramila Jayapal of Washington — is somewhat surprising, because the zero-sum nature of American health policy tends to place them on the losing end of any major system overhaul. The money it will take to provide many more services to many more patients will have to come from somewhere, the thinking goes. And the paychecks of doctors and nurses are a likely source.

That calculus has not deterred the nurses.

Perhaps that’s because they see so much time and money wasted by the bureaucracy of the current system. By most estimates, the administrative costs of American health care surpass those of any other developed nation. Or maybe it’s because of the innumerable avoidable medical crises they constantly find themselves confronting. Patients go into heart failure because they can’t afford blood pressure medication, or gamble with their diabetes for want of insulin, then turn up in the hospital needing care that’s far more expensive than any preventive measure would have been.

Or maybe they just know that a steady job with decent health benefits does not exempt anyone from the arbitrary agonies of our current system. Ms. Johnson-Camacho recalls having to discharge a patient without essential chemotherapy — not because the patient was uninsured but because his insurer refused to cover the drug that had been prescribed. “I had just finished explaining to him how important it was to take this medication faithfully,” she says. “I told him, ‘Every day you skip it is a day that the cancer has to potentially spread.’ And then we had to send him home without it.”

Ms. Johnson-Camacho says another patient — a young man with a treatable form of cancer — was so overwhelmed by the cost of his care, and so terrified of burdening his family with that cost, that he told her he was planning to kill himself.

Several proposals now working their way through Congress would aim to create just such a system. The nurses’ support for such proposals — the union has endorsed a bill put forth by Representative Pramila Jayapal of Washington — is somewhat surprising, because the zero-sum nature of American health policy tends to place them on the losing end of any major system overhaul. The money it will take to provide many more services to many more patients will have to come from somewhere, the thinking goes. And the paychecks of doctors and nurses are a likely source.

That calculus has not deterred the nurses.

Perhaps that’s because they see so much time and money wasted by the bureaucracy of the current system. By most estimates, the administrative costs of American health care surpass those of any other developed nation. Or maybe it’s because of the innumerable avoidable medical crises they constantly find themselves confronting. Patients go into heart failure because they can’t afford blood pressure medication, or gamble with their diabetes for want of insulin, then turn up in the hospital needing care that’s far more expensive than any preventive measure would have been.

Or maybe they just know that a steady job with decent health benefits does not exempt anyone from the arbitrary agonies of our current system. Ms. Johnson-Camacho recalls having to discharge a patient without essential chemotherapy — not because the patient was uninsured but because his insurer refused to cover the drug that had been prescribed. “I had just finished explaining to him how important it was to take this medication faithfully,” she says. “I told him, ‘Every day you skip it is a day that the cancer has to potentially spread.’ And then we had to send him home without it.”

Ms. Johnson-Camacho says another patient — a young man with a treatable form of cancer — was so overwhelmed by the cost of his care, and so terrified of burdening his family with that cost, that he told her he was planning to kill himself.

Anyone who has been to a hospital

or seen a family member grapple with illness has at least one story like

this. Nurses, who encounter the system daily for years or decades, have

hundreds, and they know better than most how brutally such stories can

end. “It’s barbaric,” Ms. Diederich says. “Crucial medical decisions are

being made by businessmen whose primary goal is to make a profit. Not

by medical professionals who are trying to treat their patients.”

The next remaking of American health care is still a long way off. Recent congressional hearings and a report from the Congressional Budget Office have helped to clarify the long roster of questions that lawmakers will have to address if they are serious about any of the many bills now circulating. But concrete answers to those questions have yet to materialize, and in the meantime, American patients are ambivalent. Polling suggests that a majority now support the idea of universal health care, but many are still wary of the trade-offs such an overhaul would require.

Proponents who want to persuade those skeptics would do well to have nurses make the case. “People say they are scared to have the government take control of their health care,” Ms. Diederich says. “But they should be scared of the people who are in control now.”

The next remaking of American health care is still a long way off. Recent congressional hearings and a report from the Congressional Budget Office have helped to clarify the long roster of questions that lawmakers will have to address if they are serious about any of the many bills now circulating. But concrete answers to those questions have yet to materialize, and in the meantime, American patients are ambivalent. Polling suggests that a majority now support the idea of universal health care, but many are still wary of the trade-offs such an overhaul would require.

Proponents who want to persuade those skeptics would do well to have nurses make the case. “People say they are scared to have the government take control of their health care,” Ms. Diederich says. “But they should be scared of the people who are in control now.”

Republicans are struggling to fix America’s dysfunctional health-care system

Should Democrats win in 2020, they may not fare any better

by The Economist - May 22, 2019

May 22nd 2019

Should Democrats win in 2020, they may not fare any better

“THE REPUBLICAN PARTY will soon be known

as the party of health care—you watch,” President Donald Trump declared

in March. “We’re coming up with plans.” Alas, like many of Mr Trump’s

claims, this one proved untrue. Days later, following conversations with

Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate majority leader, Mr Trump

admitted via tweet that his much-touted health-care proposal would in

fact be delayed until at least 2021 after “Republicans hold the Senate

& win back the House”.

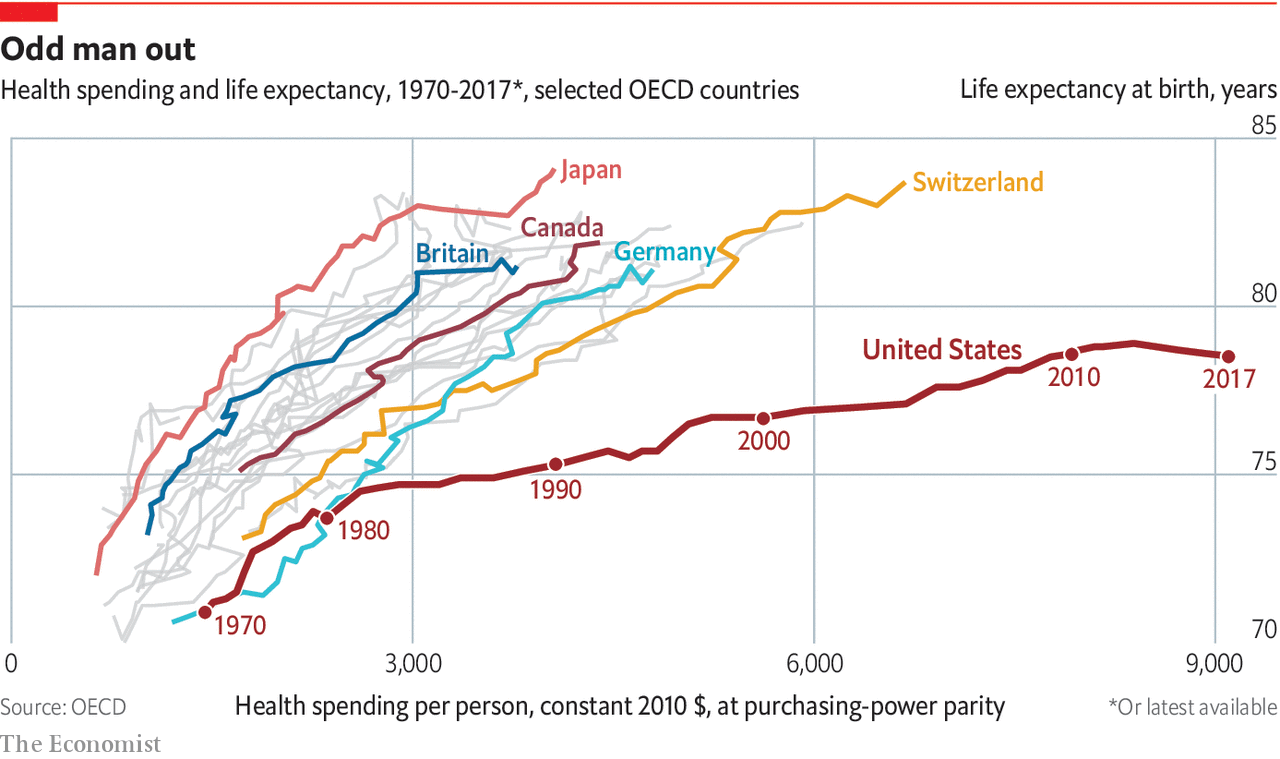

Republican reluctance to embrace health care, despite the president’s best efforts, is understandable. On the one hand, America’s health-care system is woefully dysfunctional: the country spends about twice as much on health care as other rich countries but has the highest infant-mortality rate and the lowest life expectancy (see chart). Some 30m people, including 6m non-citizens, remain uninsured. And yet, though costs remain a major concern—out-of-pocket spending on insurance continues to rise—Americans say they are generally satisfied with their own health care. Eight in ten rate the quality of their care as “good” or “excellent”. Few are in favour of dramatic reform.

So far the Trump administration has struggled to make headway. Mr Trump tried and ultimately failed to replace Obamacare, his predecessor’s signature health-care law. Since then, he has focused on proposals to rein in the cost of prescription drugs, including tying the prices of some medicines to those in other rich countries and requiring drug companies to disclose their list prices in television advertisements. This month, the president called on Congress to end “surprise” medical bills, the unexpected charges that patients often face after receiving treatment. Such measures, though welcome, are unlikely to make a dent in a system that gobbles up $3.5trn a year.

Today Democrats in Congress will have their say when the House Budget Committee holds a hearing on single-payer health care. Such a system would expand access to medical care and bring down costs by allowing the federal government to negotiate directly with providers. Polls show that Americans like the idea in theory. In practice, however, many are unwilling to accept the necessary trade-offs, including longer waiting times, less access to pricey medical treatments and higher taxes. For proof consider the experiences of Colorado, California and Vermont, left-leaning states that have all tried to implement their own single-payer systems in recent years. All of them have failed.

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/05/22/republicans-are-struggling-to-fix-americas-dysfunctional-health-care-system

Consider what already has passed or is headed for passage:

• A bill that tightens up childhood vaccination requirements by ending most exemptions.

• An act to require abortion coverage for Medicaid recipients and another to allow nurse practitioners to perform abortions.

• A bill to ensure various patient protections under the federal Affordable Care Act that have been at risk of disappearing during the Trump administration.

• Measures to increase access to lower-cost prescription drugs and to make pricing of prescriptions more transparent.

On top of that, budget priorities by Gov. Janet Mills and majority Democrats in the Legislature are heavily weighted toward health care. These include more money for treatment options to combat the opioid crisis; full implementation of Medicaid expansion, which stalled under Mills’ predecessor, Gov. Paul LePage; and additional funding for more caseworkers in child protective services.

Collectively, the measures – many of which would have been dead on arrival two years ago – have shifted Maine in a decidedly progressive direction. They also reflect a national effort by Democrats to deliver on an issue that resonates with their base of support.

“We anticipated a lot of interest in health care issues with the new administration and the new Legislature,” said Andrew MacLean, interim CEO of the Maine Medical Association. “I think we all know that, around the country in this cycle, Democrats felt like they ran on health care and won on health care, so this isn’t a surprise.”

The session has not been without partisan fights. Republicans have objected to mandatory vaccines and to expanding access to women’s reproductive rights. They also have expressed repeated concerns about increased spending, even as Mills has resisted calls from some in her party to consider new taxes.

“The narrative that Republicans don’t care about health care is false,” said Rep. Kathleen Dillingham of Oxford, the House Republican leader. “But we’re interested in making sure things are done in a fiscally responsible manner.”

Rep. Beth O’Connor of Berwick, the lead Republican on the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee, said she believes Democrats have been pushing extreme policies on health care that are out of step with Maine people.

But because Democrats hold such big advantages in both the House and Senate, and because the governor is a Democrat, they have been able to accomplish most of what they want.

“Anytime you’re out knocking on doors, this is what people are talking about,” said Sen. Geoff Gratwick, D-Bangor, who co-chairs the Health and Human Services Committee. “They want to know: How can I access whatever health care services I need and how can we make them more affordable?”

Some thorny debates – including over proposals to create a single-payer health care system – have been carried over to the next session. Others, such as whether to allow physician-assisted suicide, may fail to gain enough support. But Gratwick said his party should be pleased with its accomplishments.

“There has been a distinct shift,” he said. “And we have more to do.”

‘DRAMATIC SHIFT’ IN MEDICAID STANCE

On her first day in office, before any bills went up for debate, Mills signed an executive order to begin expanding Medicaid immediately.

Maine voters, after seeing numerous legislative attempts to expand government health care for low-income Mainers fail, passed a referendum in 2017, but LePage refused to implement expansion, even when told by the federal government to do so.

Robyn Merrill, executive director of Maine Equal Justice Partners, which advocates for low-income Mainers, said that decision set a clear tone.

“We keep having conversations with people who are accessing health care for the first time, and there is a relief in their voices,” she said. “There is no question it’s been a dramatic shift.”

Similarly, Democratic leaders made their first bill a health care-related measure: An Act to Protect Health Care Coverage for Maine Families.

That bill ensured that patients with pre-existing conditions cannot be denied coverage. It also allows children to remain on a parent’s health insurance plan to the age of 26 and prohibits any lifetime limits on coverage, provisions that also are part of the federal law.

Other moves by the Mills administration have made clear that health care is her top priority.

Her first cabinet appointee was Department of Health and Human Services Commissioner Jeanne Lambrew, who worked at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and also for many years was a policy director in the Obama White House.

Mills also created a new position – director of opioid response – and appointed longtime Maine Medical Association vice president Gordon Smith to coordinate efforts across all state agencies to fight the deadly epidemic that has threatened an entire generation.

In a statement last week, the Democratic governor said she’ll continue pushing efforts to improve the lives of Mainers.

“From more affordable, accessible health care to cheaper prescription drugs to tackling the opioid epidemic, the people of Maine sent a clear message last November that they wanted change. Now we are working to deliver it,” she said. “My administration has prioritized health care and working closely and collaboratively with the Legislature as we have been, we will continue to look for ways to improve lives by improving health care.”

Republicans, though, have cast Democratic priorities in fiscal terms. Many feel Medicaid expansion will stretch the budget for years to come, undoing progress made by LePage to reduce health care spending. They also have questioned other spending increases.

But Mills has resisted proposing any tax increases, at least during the first two years of her term. The increased spending is possible because of a strong economy that is producing more revenue.

O’Connor said it’s not just the spending, but also who is benefiting. She accused Democrats of prioritizing “able-bodied adults and non-citizens” over the “truly vulnerable.” She said there is still a waiting list for services for adults with developmental disabilities, a problem that dates back to the LePage administration.

Dillingham said Republicans have by and large supported additional spending on the opioid crisis and on child protection but wish they had a stronger voice at the table.

“I’ve tried to approach it by being respectful and focusing on policy, but we’re clearly not on the same page with some of these things,” she said.

REPUBLICANS FEEL SHUT OUT

The legislative session started slowly, as most sessions do, but as debate has intensified, health care has taken center stage.

On the vaccination bill, hundreds of people turned out for the public hearing and the committee received more than 1,000 pieces of testimony. The abortion bills drew large crowds as well.

At a time when several other states have passed laws to restrict abortions, the fact that Maine has improved access is noteworthy.

Again, that would not have been possible at any point since 2010, when LePage was elected and Republicans controlled the Legislature.

Similarly, the narrowly-passed bill to ensure children who attend public schools have up-to-date vaccinations is likely not something that would have passed in previous Legislatures, much less survived an almost-certain veto by LePage.

O’Connor and Dillingham said both are examples of “extreme left” policies that Democrats will come to regret.

Dillingham, who has a less combative approach than previous Republican leaders, said she has tried to engage with majority Democrats but hasn’t seen much willingness to compromise.

There have been some exceptions. Just last week, the insurance committee unanimously passed a bill that would require insurers to cover mental health and substance use disorder treatment in the same manner as other medical conditions. The bill also bans practices that restrict prescription drug coverage for substance use disorder.

MacLean, speaking for the Maine Medical Association, said his members have been supportive of most of the measures that have passed.

“We always have a fair amount of health care legislation every session given the portion of the economy it occupies,” he said. “What’s interesting right now is, from a budget standpoint, we’re not talking about cuts to services.”

LePage, with help from legislative Republicans, prioritized reducing spending in health care, especially social services.

Supporters praised his fiscal stewardship. Critics argued the cuts were draconian and had led to bigger problems.

Gratwick, the Bangor Democratic lawmaker, said he sees this legislative session and the next as opportunities to consider long-term investments.

He acknowledged that spending in health care has increased to an unsustainable level but said figuring out a way to lower the actual cost of health care should be the goal, not cutting services.

But Gratwick said serving as co-chair of the Health and Human Services Committee has given him a window into how the state has failed vulnerable populations.

“We have under-funded, and I think there is bipartisan guilt because it started during the Baldacci administration and worsened under the LePage administration,” he said.

One proposal that is still being debated is a bill that would add a comprehensive dental benefit – including preventive, diagnostic and restorative care – for more than 100,000 adult Mainers who have Medicaid. Maine would join 33 states that have such a benefit.

The dental bill could be doomed by its cost, which is estimated at $7 million to $19 million a year. But it provides a good example of how prioritizing prevention can require high spending up front while saving money in the long term.

Maine now offers routine dental care for children on Medicaid, but adults are only covered for emergency care, such as tooth extractions. Merrill, at Maine Equal Justice Partners, says it makes more sense to offer adults preventive care rather that emergency tooth extractions.

“I think there is more energy around being more thoughtful and looking out further when it comes to health care,” Merrill said of the current Legislature’s approach to health care issues.

Many of those discussions will spill over into the next session, where Democrats will still get to set the agenda.

O’Connor said Republicans will continue pushing for their own values.

“We’re not trying to be obstructionist,” she said. “I’ll always vote for good policy.”

https://www.pressherald.com/2019/05/26/health-care-has-dominated-legislative-session/

Republican reluctance to embrace health care, despite the president’s best efforts, is understandable. On the one hand, America’s health-care system is woefully dysfunctional: the country spends about twice as much on health care as other rich countries but has the highest infant-mortality rate and the lowest life expectancy (see chart). Some 30m people, including 6m non-citizens, remain uninsured. And yet, though costs remain a major concern—out-of-pocket spending on insurance continues to rise—Americans say they are generally satisfied with their own health care. Eight in ten rate the quality of their care as “good” or “excellent”. Few are in favour of dramatic reform.

So far the Trump administration has struggled to make headway. Mr Trump tried and ultimately failed to replace Obamacare, his predecessor’s signature health-care law. Since then, he has focused on proposals to rein in the cost of prescription drugs, including tying the prices of some medicines to those in other rich countries and requiring drug companies to disclose their list prices in television advertisements. This month, the president called on Congress to end “surprise” medical bills, the unexpected charges that patients often face after receiving treatment. Such measures, though welcome, are unlikely to make a dent in a system that gobbles up $3.5trn a year.

Today Democrats in Congress will have their say when the House Budget Committee holds a hearing on single-payer health care. Such a system would expand access to medical care and bring down costs by allowing the federal government to negotiate directly with providers. Polls show that Americans like the idea in theory. In practice, however, many are unwilling to accept the necessary trade-offs, including longer waiting times, less access to pricey medical treatments and higher taxes. For proof consider the experiences of Colorado, California and Vermont, left-leaning states that have all tried to implement their own single-payer systems in recent years. All of them have failed.

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/05/22/republicans-are-struggling-to-fix-americas-dysfunctional-health-care-system

Health care dominates Maine’s legislative session

by Eric Russell - Portland Sunday Telegram - May 26, 2019

When the book closes on the 129th Maine Legislature, it may well be remembered as the health care session.

Consider what already has passed or is headed for passage:

• A bill that tightens up childhood vaccination requirements by ending most exemptions.

• An act to require abortion coverage for Medicaid recipients and another to allow nurse practitioners to perform abortions.

• A bill to ensure various patient protections under the federal Affordable Care Act that have been at risk of disappearing during the Trump administration.

• Measures to increase access to lower-cost prescription drugs and to make pricing of prescriptions more transparent.

On top of that, budget priorities by Gov. Janet Mills and majority Democrats in the Legislature are heavily weighted toward health care. These include more money for treatment options to combat the opioid crisis; full implementation of Medicaid expansion, which stalled under Mills’ predecessor, Gov. Paul LePage; and additional funding for more caseworkers in child protective services.

Collectively, the measures – many of which would have been dead on arrival two years ago – have shifted Maine in a decidedly progressive direction. They also reflect a national effort by Democrats to deliver on an issue that resonates with their base of support.

“We anticipated a lot of interest in health care issues with the new administration and the new Legislature,” said Andrew MacLean, interim CEO of the Maine Medical Association. “I think we all know that, around the country in this cycle, Democrats felt like they ran on health care and won on health care, so this isn’t a surprise.”

The session has not been without partisan fights. Republicans have objected to mandatory vaccines and to expanding access to women’s reproductive rights. They also have expressed repeated concerns about increased spending, even as Mills has resisted calls from some in her party to consider new taxes.

“The narrative that Republicans don’t care about health care is false,” said Rep. Kathleen Dillingham of Oxford, the House Republican leader. “But we’re interested in making sure things are done in a fiscally responsible manner.”

Rep. Beth O’Connor of Berwick, the lead Republican on the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee, said she believes Democrats have been pushing extreme policies on health care that are out of step with Maine people.

But because Democrats hold such big advantages in both the House and Senate, and because the governor is a Democrat, they have been able to accomplish most of what they want.

“Anytime you’re out knocking on doors, this is what people are talking about,” said Sen. Geoff Gratwick, D-Bangor, who co-chairs the Health and Human Services Committee. “They want to know: How can I access whatever health care services I need and how can we make them more affordable?”

Some thorny debates – including over proposals to create a single-payer health care system – have been carried over to the next session. Others, such as whether to allow physician-assisted suicide, may fail to gain enough support. But Gratwick said his party should be pleased with its accomplishments.

“There has been a distinct shift,” he said. “And we have more to do.”

‘DRAMATIC SHIFT’ IN MEDICAID STANCE

On her first day in office, before any bills went up for debate, Mills signed an executive order to begin expanding Medicaid immediately.

Maine voters, after seeing numerous legislative attempts to expand government health care for low-income Mainers fail, passed a referendum in 2017, but LePage refused to implement expansion, even when told by the federal government to do so.

Robyn Merrill, executive director of Maine Equal Justice Partners, which advocates for low-income Mainers, said that decision set a clear tone.

“We keep having conversations with people who are accessing health care for the first time, and there is a relief in their voices,” she said. “There is no question it’s been a dramatic shift.”

Similarly, Democratic leaders made their first bill a health care-related measure: An Act to Protect Health Care Coverage for Maine Families.

That bill ensured that patients with pre-existing conditions cannot be denied coverage. It also allows children to remain on a parent’s health insurance plan to the age of 26 and prohibits any lifetime limits on coverage, provisions that also are part of the federal law.

Other moves by the Mills administration have made clear that health care is her top priority.

Her first cabinet appointee was Department of Health and Human Services Commissioner Jeanne Lambrew, who worked at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and also for many years was a policy director in the Obama White House.

Mills also created a new position – director of opioid response – and appointed longtime Maine Medical Association vice president Gordon Smith to coordinate efforts across all state agencies to fight the deadly epidemic that has threatened an entire generation.

In a statement last week, the Democratic governor said she’ll continue pushing efforts to improve the lives of Mainers.

“From more affordable, accessible health care to cheaper prescription drugs to tackling the opioid epidemic, the people of Maine sent a clear message last November that they wanted change. Now we are working to deliver it,” she said. “My administration has prioritized health care and working closely and collaboratively with the Legislature as we have been, we will continue to look for ways to improve lives by improving health care.”

Republicans, though, have cast Democratic priorities in fiscal terms. Many feel Medicaid expansion will stretch the budget for years to come, undoing progress made by LePage to reduce health care spending. They also have questioned other spending increases.

But Mills has resisted proposing any tax increases, at least during the first two years of her term. The increased spending is possible because of a strong economy that is producing more revenue.

O’Connor said it’s not just the spending, but also who is benefiting. She accused Democrats of prioritizing “able-bodied adults and non-citizens” over the “truly vulnerable.” She said there is still a waiting list for services for adults with developmental disabilities, a problem that dates back to the LePage administration.

Dillingham said Republicans have by and large supported additional spending on the opioid crisis and on child protection but wish they had a stronger voice at the table.