The Insulin Wars

by Danielle Ofri - NYT - January 18, 2019

“Doctor, could you please redo my insulin prescription? The

one you gave me is wrong.” My patient’s frustration was obvious over

the phone. She was standing at the pharmacy, unable to get her diabetes

medication.

We had gone through this just the week before. I’d

prescribed her the insulin she’d been on, at the correct dosage, but

when she showed up at her pharmacy she learned that her insurance

company no longer covered that brand. After a series of phone messages

back and forth, I’d redone the prescription with what I’d thought was

the correct insulin, but I was apparently wrong. Again.

Between 2002 and 2013,

prices tripled

for some insulins. Many cost around $300 a vial, without any viable

generic alternative. Most patients use two or three vials a month, but

others need the equivalent of four.

Self-rationing has become common

as patients struggle to keep up. In the short term, fluctuating blood

sugar levels can lead to confusion, dehydration, coma, even

death.

In the long term, poorly controlled diabetes is associated with heart

attacks, strokes, blindness, amputation and the need for dialysis.

The

exorbitant prices confound patients and doctors alike since insulin is

nearly a century old now. The pricing is all the more infuriating when

one considers that

the discoverers of insulin sold the patent for $1 each to ensure that the medication would be affordable. Today the three main manufacturers of insulin are

facing a lawsuit accusing them of deceptive pricing schemes, but it could be years before this yields any changes.

There

are several reasons that insulin is so expensive. It is a biologic

drug, meaning that it’s produced in living cells, which is a difficult

manufacturing process. The bigger issue, however, is that companies

tweak their formulations

so they can get new patents, instead of working to create cheaper

generic versions. This keeps insulin firmly in brand-name territory,

with prices to match.

But the real ignominy (and the meat of the

lawsuit) is the dealings between the drug manufacturers and the

insurance companies. Insurers use pharmacy benefit managers, called

P.B.M.s, to negotiate prices with manufacturers. Insurance programs

represent huge markets, so manufacturers compete to offer good deals.

How to offer a good deal? Jack up the list price, and then offer the

P.B.M.s a “discount.”

This pricing is, of course, hidden from most patients, except those without insurance, who have to pay full freight. Patients

with

insurance live with the repercussions of constantly changing coverage

as P.B.M.s chase better discounts from different manufacturers.

All

insurance companies periodically change which medications they cover,

but insulin is in a whirlwind class by itself because of the staggering

sums of money involved. “Short-acting” is supposed to be a category of

insulin, but now it appears to be its category of insurance coverage. My

patient’s “preferred insulin” changed three times in a year, so each

time she went to the pharmacy, her prescription was rejected.

On

the doctor's end, it’s an endless game of catch-up. Lantus was covered,

but now it’s Basaglar: rewrite all the prescriptions for all your

patients. Oops, now it’s Levemir: rewrite them all again. NovoLog was

covered, then it was Humalog, but now it’s Admelog. If it’s Tuesday, it

must be Tresiba.

It’s a colossal

time-waster, as patients, pharmacists and doctors log hours upon hours

calling, faxing, texting and emailing to keep up with whichever insulin

is trending. It’s also dangerous, as patients can end up without a

critical medication for days, sometimes weeks, waiting for these

bureaucratic kinks to get ironed out.

Lost in this communal

migraine is that this whole process is corrosive to the doctor-patient

relationship. I knew that my patient wasn’t angry at me personally, but

her ire came readily through the phone. No doubt this reflected

desperation — she’d run out of insulin before and didn’t want to end in

the emergency room on IV fluids, as she had the last time. Frankly, I

was pretty peeved myself. By this point I’d already written enough

insulin prescriptions on her account to fill a sixth Book of Moses. I’d

already called her insurance company and gotten tangled in phone trees

of biblical proportions.

This time I called her pharmacy. A

sympathetic pharmacist was willing to work with me, and I stayed on the

phone with her as we painstakingly submitted one insulin prescription

after another. The first wasn’t covered. The second wasn’t covered. The

third was. But before we could sing the requisite hosannas, the

pharmacist informed me that while the insulin was indeed covered, it was

not a “preferred” medication. That meant there was a $72-per-month

co-payment, something that my patient would struggle to afford on her

fixed income.

“So just tell me which is the preferred insulin,” I told the pharmacist briskly.

There was a pause before she replied. “There isn’t one.”

This was a new low — an insurance company now had no

insulins on its top tier. Breaking the news to my patient was

devastating. We had a painful conversation about how she would have to

reconfigure her life in order to afford this critical medication.

It

suddenly struck me that insurance companies and drug manufacturers had

come upon an ingenious business plan: They could farm out their dirty

work to the doctors and the patients. Let the doctors be the ones to

navigate the bureaucratic hoops and then deliver the disappointing news

to our patients. Let patients be the ones to figure out how to ration

their medications or do without.

Congress and the Food and Drug

Administration need to tame the Wild West of drug pricing. When there’s

an E. coli outbreak that causes illness and death, we rightly expect our

regulatory bodies to step in. The outbreak of insulin greed is no

different.

It is hard to know where to

direct my rage. Should I be furious at the drug manufacturers that

refuse to develop generics? Should I be angry at the P.B.M.s and

insurance companies that juggle prices and formularies to maximize

profits, passing along huge co-payments if they don’t get a good enough

deal? Should I be indignant at our elected officials who seem content to

let our health care system be run by for-profit entities that will

always put money before patients?

The answer is all of the above. But what’s

most

enraging is that drug manufacturers, P.B.M.s and insurance companies

don’t have to pick up the pieces from the real-world consequences of

their policies. That falls to the patients.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/18/opinion/cost-insurance-diabetes-insulin.html?login=email&auth=login-email

The Strange Marketplace for Diabetes Test Strips

by Ted Alcorn - NYT - January 14, 2019

On most afternoons, people arrive from across New York City

with backpacks and plastic bags filled with boxes of small plastic

strips, forming a line on the sidewalk outside a Harlem storefront.

Hanging from the awning, a banner reads: “Get cash with your extra diabetic test strips.”

Each

strip is a laminate of plastic and chemicals little bigger than a

fingernail, a single-use diagnostic test for measuring blood sugar. More

than 30 million Americans have Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, and most use

several test strips daily to monitor their condition.

But at this

store on W. 116th Street, each strip is also a lucrative commodity,

part of an informal economy in unused strips nationwide. Often the

sellers are insured and paid little out of pocket for the strips; the

buyers may be underinsured or uninsured, and unable to pay retail

prices, which can run well over $100 for a box of 100 strips.

Some

clinicians are surprised to learn of this vast resale market, but it

has existed for decades, an unusual example of the vagaries of American

health care. Unlike the resale of prescription drugs, which is

prohibited by law, it is generally legal to resell unused test strips.

And

this store is far from the only place buying. Mobile phones light up

with robo-texts: “We buy diabetic test strips!” Online, scores of

companies thrive with names like TestStripSearch.com and

QuickCash4TestStrips.com.

“I’m taking advantage, as are my peers,

of a loophole,” said the owner of one popular site, who asked that his

name not be used. “We’re allowed to do that. I don’t even think we

should be, frankly.”

Test strips were first developed in 1965 to

provide an immediate reading of blood sugar, or glucose, levels. The

user pricks a finger, places a drop of blood on the strip, and inserts

it into a meter that provides a reading.

The test strips were

created for use in doctors’ offices, but by 1980 medical-device

manufacturers had designed meters for home use. They became the standard

of care for many people with diabetes, who test their blood as often as

ten times a day.

Test strips are a multi-billion-dollar industry.

A 2012 study

found that among insulin-dependent patients who monitor their blood

sugar, strips accounted for nearly one-quarter of pharmacy costs. Today,

four manufacturers account for half of global sales.

In a retail pharmacy, name-brand strips command high

prices. But like most goods and services in American health care, that

number doesn’t reflect what most people pay.

The sticker price is

the result of behind-the-scenes negotiations between the strips’

manufacturer and insurers. Manufacturers set a high list price and then

negotiate to become an insurer’s preferred supplier by offering a hefty

rebate.

These transactions are invisible to the insured consumer,

who might cover a copay, at most. But the arrangement leaves the

uninsured — those least able to pay — paying sky-high sticker prices out

of pocket. Also left out are the underinsured, who may need to first

satisfy a high deductible.

For a patient testing their blood many

times a day, paying for strips out-of-pocket could add up to thousands

of dollars a year. Small wonder, then, that a gray market thrives. The

middlemen buy extras from people who obtained strips through insurance,

at little cost to themselves, and then resell to the less fortunate.

That

was the opportunity that caught Chad Langley’s eye. He and his twin

brother launched the website Teststripz.com to solicit test strips from

the public for resale. Today they buy strips from roughly 8,000 people;

their third-floor office in Redding, Mass., receives around 100

deliveries a day.

The amount the Langleys pay depends on the

brand, expiration date and condition, but the profit margins are

reliably high. For example, the brothers will pay $35 plus shipping for a

100-count box of the popular brand Freestyle Lite in mint condition.

The Langleys sell the box for $60. CVS, by contrast, retails the strips for $164.

The

Langleys are mainly buying up excess strips from insured patients who

have been flooded with them, sometimes even when not medically

necessary.

Although patients who manage

their diabetes with non-insulin medications or with diet and exercise

needn’t test their blood sugar daily,

a recent analysis of insurance claims found that nearly one in seven patients still used test strips regularly.

‘It’s a tiny little piece of plastic that’s super cheap to manufacture, and they’ve managed to make a cash cow out of it.’

Gretchen Obrist

The

market glut is also a consequence of a strategy adopted by

manufacturers to sell patients proprietary meters designed to read only

their brand of strips. If a patient’s insurer shifts her to a new brand,

she must get a new meter, often leaving behind a supply of useless

strips.

While some resellers use websites like Amazon or eBay to

market strips directly to consumers, the biggest profits are in

returning them to retail pharmacies, which sell them as new and bill the

customer’s insurance the full price.

The insurer reimburses the

pharmacy the retail price and then demands a partial rebate from the

manufacturer — but it’s a rebate the manufacturer has paid already for

this box of strips.

Glenn Johnson, general manager for market access at Abbott

Diabetes Care, which makes about one in five strips purchased in the

United States, said manufacturers lose more than $100 million in profits

a year this way, much of it in New York, California and Florida.

The company supported

a new California

law that prohibits pharmacies from acquiring test strips from any but

an authorized list of distributors. Mr. Johnson said he has spoken with

lawmakers about similar efforts in Florida, New Jersey, New York and

Ohio.

Such measures leave intact the inflated retail prices that

make the gray market possible and which critics say benefit

manufacturers and their retail intermediaries, pharmacy benefit

managers.

In a lawsuit against P.B.M.’s and

the dominant test strip manufacturers filed in New Jersey, consumer

advocates presented data showing that the average wholesale price for

test strips has risen as much as 70 percent over the last decade.

They

alleged that this has allowed the defendants to pocket an unfair

portion of the rebates. The price of a strip would be much lower if it

wasn’t fattened by profiteering, said Gretchen Obrist, one of the

lawyers who brought the case.

“It’s a tiny little piece of plastic

that’s super cheap to manufacture, and they’ve managed to make a cash

cow out of it,” she said.

To justify the rising price of strips,

manufacturers point to advances in engineering that have made the strips

smaller and more convenient to use. But there is little evidence those

features have improved health outcomes for people with diabetes — and

with increasingly unaffordable prices, the newfangled test strips may be

even less accessible.

The markups on strips look particularly stark when compared to the cost of producing them.

“Test

strips are basically printed, like in a printing press,” said David

Kliff, who publishes a newsletter on diabetes. “It’s not brain surgery.”

He estimated the typical test strip costs less than a dime to make.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/14/health/diabetes-test-strips-resale.html

Seven in 10 Maintain Negative View of U.S. Healthcare System

by Justin McCarthy - Gallup - January 14, 2019

- 70% say U.S. healthcare has major problems/is in state of crisis

- Overall perceptions stable, but party views have changed

- About six in seven Democrats now have negative assessments of the system

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Seventy percent of Americans describe the current

U.S. healthcare system as being "in a state of crisis" or having "major

problems." This is consistent with the 65% to 73% range for this figure

in all but one poll since Gallup first asked the question in 1994.

In that one poll -- conducted right after the 9/11 attacks in 2001 --

just 49% of Americans said the U.S. healthcare system had major

problems or was in crisis. This was because of Americans' heightened

concerns about terrorism after the attacks, which temporarily

altered their views and behaviors on a variety of issues.

The latest data are from Gallup's annual Healthcare poll, conducted Nov. 1-11.

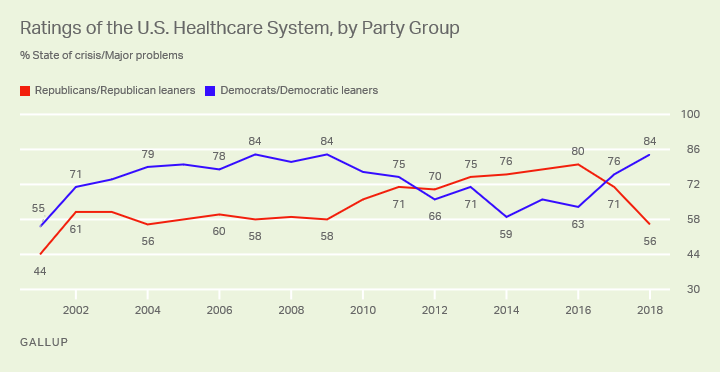

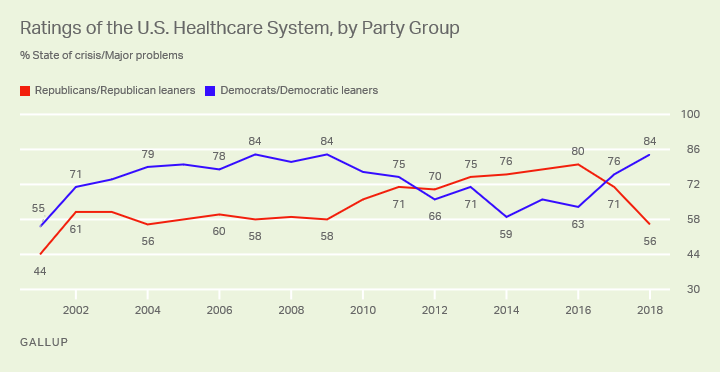

About Six in Seven Democrats Rate the Healthcare System Negatively

Although the percentage of Americans saying U.S. healthcare has major

problems or is in crisis has been fairly flat over the past two

decades, Democrats' and Republicans' views have changed within that time

frame.

From 2001 to 2009, Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents were

considerably more likely than Republicans and Republican-leaning

independents to say healthcare had major problems or was in crisis.

Democrats' negative assessments then decreased in the rest of President

Barack Obama's first term, after passage of the Affordable Care Act

(ACA) in 2010, at the same time that Republicans' concerns mounted. By

2012, the lines crossed, so that during most of Obama's second term,

Republicans were significantly more likely than Democrats to perceive

significant or critical problems in the healthcare system.

Now, with Republican President Donald Trump in office, partisan views

have flipped again, with Democrats more likely to be concerned.

The difference between the two major parties on this measure was just

five percentage points in 2017, Trump's first year, when 76% of

Democrats and 71% of Republicans said healthcare had major problems or

was in crisis. This expanded to a 28-point gap in 2018, when 84% of

Democrats and 56% of Republicans expressed these views -- the largest

partisan gap on this measure in Gallup's trend since 2001.

The 2018 poll was conducted on the heels of last year's midterm

elections, in which Democratic candidates highlighted key problems with

the healthcare system -- especially coverage.

Although most Americans, including majorities of Republicans and

Democrats, give the healthcare system a pessimistic diagnosis, when

asked specifically about the quality of U.S. healthcare, 55% rate it

positively. Smaller percentages have positive reviews of U.S. healthcare

coverage (34%) and costs (20%). Americans rate

cost and access as the greatest health problems facing the country.

More broadly, Gallup has found that Americans are much more positive in

their assessments of their personal healthcare than they are about the healthcare system nationally.

Bottom Line

Barring any major breakthroughs in healthcare reform, it's difficult

to imagine Americans' dim assessments of the state of U.S. healthcare

changing anytime soon, given the mostly stable trend Gallup has recorded

over nearly a quarter of a century.

The last major feat

in healthcare policy reform was met by more disapproval than approval

from Americans for many years, and the public's preferences for next

steps on the ACA provide an unclear path for policymakers to follow to

improve perceptions of the system.

Democratic efforts in the House of Representatives to protect the ACA

will likely hit roadblocks with a GOP-controlled Senate and White

House, and even some Democratic approaches to lowering drug prices are

unlikely to receive Republicans' support. 2018 GOP congressional

candidates campaigned on protection for

those with pre-existing conditions, which more than a quarter of Americans report having, but there is already disagreement between the two major parties on how to provide that.

View complete question responses and trends.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/245873/seven-maintain-negative-view-healthcare-system.aspx

Report raises alarm about physician burnout - The Boston Globe

By Priyanka Dayal McCluskey - The Boston Glober - January 17, 2019

Physician burnout has reached alarming levels and now amounts to a

public health crisis that threatens to undermine the doctor-patient

relationship and the delivery of health care nationwide, according to a

report from Massachusetts doctors to be released Thursday.

The report — from the Massachusetts Medical Society, the

Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association, and the Harvard T.H.

Chan School of Public Health — portrays a profession struggling with the

unyielding demands of electronic health record systems and ever-growing

regulatory burdens.

It urges hospitals and medical practices to

take immediate action by putting senior executives in charge of

physician well-being and by giving doctors better access to mental

health services. The report also calls for significant changes to make

health record systems more user-friendly.

While burnout has long been a worry in the profession, the report

reflects a newer phenomenon — the draining documentation and data entry

now required of doctors. Today’s electronic record systems are so

complex that a simple task, such as ordering a prescription, can take

many clicks.

Doctors typically spend two hours on computer work for every hour

they spend with patients, the report said. Much of this happens after

they leave the office; they call it “pajama time.”

Medicine has become more regulated and complex over the past several

years, generating what doctors often consider to be meaningless busywork

detached from direct patient care. That’s when they start to feel

disheartened, authors of the report said.

“A lot of physicians

feel they are on a treadmill, on a conveyor belt,” said Dr. Alain A.

Chaoui, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society and a family

doctor in Peabody. “They’re not afraid of work — it’s the work that has

nothing to do with the patients that makes physicians unhappy. And it

makes the patients unhappy, because they feel the system is failing

them.”

Chaoui and the report’s other authors reviewed dozens of

studies to develop their paper, which they described as “a call to

action” for providers, insurers, government agencies, and health

technology companies. The report does not specifically address burnout

of nurses or other health care workers — only doctors.

Surveys indicate that 50 percent to as many as 78 percent of doctors

have at some point experienced burnout — described as emotional

exhaustion and disengagement from their work — as they contend with the

realities of modern medicine.

Doctors must comply with a host of

federal reporting requirements and insurance company rules. As insurers

set tighter restrictions aimed at controlling costs, for example,

doctors spend more time on the phone to persuade insurers to reimburse

them for certain tests and services, they say.

And much of the day is spent typing, pointing, and clicking in electronic health records, which are

notoriously time-consuming and difficult to use.

While doctors acknowledge that electronic records hold many advantages

over paper charts, they say computers have become an obstacle —

literally — that can hinder conversation with patients.

Studies show that burnout has costly consequences for doctors as well as patients, and for the health care system as a whole.

When

doctors are less engaged, patients are less satisfied. Burned-out

physicians are more likely to make mistakes. They’re also more likely to

reduce their hours or retire early. This affects their employer’s

bottom line: Each departing doctor costs as much as $500,000 to $1

million to replace, according to one study.

In a national survey of doctors published last year, 10.5 percent

reported a major medical error in the prior three months. Those who

reported errors were more likely to experience burnout, fatigue, and

suicidal thoughts.

To tackle the problem, the report says, physicians need access to

mental health care without stigma or fear of losing their right to

practice. The authors argue that state licensing boards should not ask

probing questions about a physician’s mental health but focus instead on

his or her ability to practice medicine safely.

“We want to

normalize it. We want to encourage people to ask for help when they need

it,” said Dr. Steven Defossez, vice president of clinical integration

at the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association. “There is

certainly a fear that keeps people from accessing services today.”

Asking

doctors to manage their feelings on their own is not enough, the report

says; it demands that major health care organizations take burnout

seriously by hiring a chief wellness officer — a senior executive in

charge of tracking burnout and helping to improve physician wellness.

“This

is not about more yoga classes in the hospital,” said Dr. Ashish K.

Jha, a Harvard professor who worked on the report. “This is about

someone at the highest level of the organization who is responsible for

making sure that the workforce is healthy and thriving.”

“We think the responsibility lies with the system that has created these problems,” not with individual doctors, Jha added.

In

response to the burnout “epidemic,” officials at Stanford Medicine in

California hired Dr. Tait Shanafelt from the Mayo Clinic as their first

chief wellness officer in 2017. Stanford also trains doctors from around

the country in physician wellness.

Shanafelt said his job is to identify “problem areas” and develop a coordinated approach to address the problems.

“Part

of our role is, when other key strategies or initiatives are being

discussed, [to think about] the concept of how they’re going to impact

our people,” he said.

Physician burnout has spawned numerous

studies that have raised awareness of the issue in recent years, and

several Massachusetts health systems have begun working to address it.

Last January, Boston Medical Center named Dr. Susannah Rowe, an

ophthalmologist, to the new role of associate chief medical officer for

wellness and professional vitality. Hospital officials said they are

working on initiatives to reduce administrative burdens for doctors and

implement flexible work schedules.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

asked its physicians how they felt about their work in 2017 and plans to

repeat the survey this year, though it has not published the results.

“We’re

really in this to make our physicians professionally fulfilled — not

just stop burnout,” said Dr. Jessica C. Dudley, chief medical officer of

the Brigham and Women’s Physicians Organization.

Based on physicians’ feedback, the Brigham decided to provide

individualized training on the hospital’s complicated health record

software. The training was held at the clinics where doctors practice,

Dudley said.

Thursday’s report from the medical society, hospital

association, and Harvard also urges medical software companies to design

more efficient systems, including by developing apps that doctors can

download to help with certain tasks, such as documenting patient visits.

The

report concludes with a warning: “If left unaddressed, the worsening

crisis threatens to undermine the very provision of care, as well as

eroding the mental health of physicians across the country.”

https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2019/01/17/report-raises-alarm-about-physician-burnout/9CGdUc0eEOnobtSUiX5EIK/story.html?

Doctor burnout is real. And it’s dangerous

by Alan Chaoui, Steven Defossez and Michelle Williams - Boston Globe - January 17, 2019

Burnout — a condition characterized by emotional

exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of reduced effectiveness in the

workforce — impacts all caregivers and, in particular, threatens to

undermine the physician workforce, endangering our health care system.

So

profound it has been described as “moral injury,” burnout results from a

collision of norms between the physician’s mission to provide care and

increasing bureaucratic demands of a new era.

Evidence shows the worsening scope,

severity, and impact of this public health crisis: Frustrating computer

interfaces have crowded out engagement with patients, extending already

long work days as physicians and all caregivers struggle to keep up

with a soaring burden of administrative tasks. Nearly half of all

physicians experience burnout in some form, and the number will continue

to grow. The consequences of this epidemic on patients and physicians

are clear, and physicians have affirmed a necessary and unwavering

commitment to spearhead changes that will lead to solutions.

Burned-out physicians who choose not to leave the

profession are more likely to reduce their work hours. This reduction

is already equivalent to losing the graduates of seven medical schools

every year. Recruiting and replacing one physician can cost employers as

much as $1 million. Burned-out physicians are also unable to provide

the best care, with

evidence suggesting that burnout is associated with increased medical errors.

We cannot improve patient experience and

population health while reducing health care costs without a strong and

engaged physician workforce.

What can we do? A lot. A

new white paper

produced by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the Harvard

Global Health Institute, the Massachusetts Health and Hospital

Association, and the Massachusetts Medical Society, proposes three key

recommendations.

First, we must support

proactive and confidential mental health treatment for burned-out

physicians and expand outreach, particularly for trainees, who are at a

vulnerable stage of their careers. Physicians seeking care face stigma

and professional obstacles, including probing questions about mental

health in their medical license process. We recommend such questions be

limited or eliminated. If they are included, these questions should

focus on impairments impacting the physician’s current practice and

competence, in the same way questions about physical health do.

Second,

we must improve the usability of electronic health records, or EHRs.

Physicians must now spend much of an appointment clicking and typing,

eyes glued to a computer monitor rather than engaged with the patient.

The ever-increasing array of reporting systems and unhelpful alerts not

only interfere with patient interaction, but also force physicians to

spend additional hours completing administrative tasks that limit

patient interaction and can harm patient experience and care.

Fortunately, there are opportunities for

improvements that involve more user-friendly mobile apps. We are also

seeing the first results of a drive to make it easier for EHRs from one

office or hospital to share critical patient information with another

system (interoperability). Further, there is technical innovation under

development around streamlining some of the most burdensome,

time-consuming, and demoralizing processes for obtaining insurance

company approvals for services and patient referrals.

Improvements

by EHR vendors and payers will require action by state and federal

agencies. The US Department of Health and Human Services recently

acknowledged that the burden of EHRs contributes to burnout, in its

draft “

Strategy on Reducing Regulatory and Administrative Burden Relating to the Use of Health IT and EHRs.”

We encourage physicians and health care organizations to submit

comments on how to make sure EHRs support both patient care and

physician workflow.

Third, and most

important for the long term, we call for the appointment of

executive-level chief wellness officers at every major health care

organization. Several major organizations, including Stanford Medicine

and Kaiser Permanente, have already done so, recognizing that burnout

among physicians and clinical and support staff across every layer of

their organization demands action. This is a welcome and necessary

development and must be the first step in creating a professional

learning community of health care leaders and providers sharing

successful burnout remediation strategies. Over time, physician and

clinician wellness among all health care providers must become a

“dashboard” item for institutional CEOs and boards of directors. We

believe strongly that there will be a substantial financial and patient

experiential return on investment.

This crisis could not be more

urgent. If physician burnout continues to worsen, it will degrade the

quality of health care our physicians and hospitals provide, in addition

to increasing the profound harm to physician mental health resulting

from the serious misalignment between the demands placed on them and

their core mission of providing care. Fortunately, we have the tools to

make changes. We need to take better care of our physicians and all

caregivers so that they can continue to take the best care of us.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2019/01/17/doctor-burnout-real-and-dangerous/LpEgCCzyWhHou6qketcGQK/story.html?et_rid=1744895461&s_campaign=todayinopinion:newsletter

Editor's Note -

The preceding two clippings from the Boston Globe are prime examples of treating the symptoms and ignoring the underlying pathology. While they do a decent job of describing the symptoms of the disease they cover (physician burnout), they totally ignore the underlying pathology that is causing the disease - the excessive complexity of our health insurance system and its excessive focus on the business of medicine rather than on its healing mission. That’s not especially remarkable - clueless “leaders” are a dime a dozen. But the recommendations of the cited report are in fact the product of two Harvard-affiliated institutions and two powerful trade (excuse me - professional) associations.

The disease afflicting American medicine is widespread and deep rooted indeed..

-SPC

GoFundMe CEO: ‘Gigantic Gaps’ In Health System Showing Up In Crowdfunding

by Rachel Bluth - Kaiser Health News - January 16, 2019

Scrolling through the GoFundMe website reveals seemingly an endless

number of people who need help or community support. A common theme: the

cost of health care.

It didn’t start out this way. Back in 2010, when the crowdfunding

website began, it suggested fundraisers for “ideas and dreams,” “wedding

donations and honeymoon registry” or “special occasions.” A spokeswoman

said the bulk of collection efforts from the first year were “related

to charities and foundations.” A category for medical needs existed, but

it was farther down the list.

In the nine years since, campaigns to pay for health care have reaped

the most cash. Of the $5 billion the company says it has raised, about a

third has been for medical expenses from more than 250,000 medical

campaigns conducted annually.

Take, for instance, the 25-year-old California woman who had a stroke

and “needs financial support for rehabilitation, home nursing, medical

equipment and uncovered medical expenses.” Or the Tennessee couple who

want to get pregnant, but whose insurance doesn’t cover the $20,000

worth of “medications, surgeries, scans, lab monitoring, and

appointments [that] will need to be paid for upfront and out-of-pocket”

for in vitro fertilization.

The prominence of the medical category is the symptom of a broken

system, according to CEO Rob Solomon, 51, who has a long tech résumé as

an executive at places like Groupon and Yahoo. He said he never realized

how hard it was for some people to pay their bills: “I needed to

understand the gigantic gaps in the system.”

This year,

Time Magazine named Solomon one of the 50 most influential people in health care.

“We didn’t build the platform to focus on medical expenses,” Solomon

said. But it turned out, he said, to be one of those “categories of

need” with which many people struggle.

Solomon talked to Kaiser Health News’ Rachel Bluth about his

company’s role in financing health care and what it says about the

system when so many people rely on the kindness of strangers to get

treatment. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: KHN

and other news outlets have reported that hospitals often advise

patients to crowdfund their transplants. It’s become almost

institutionalized to use GoFundMe. How do you feel about that?

It saddens me that this is a reality. Every single day on GoFundMe we

see the huge challenges people face. Their stories are heartbreaking.

Some progress has been made here and there with the Affordable Care

Act, and it’s under fire, but there’s ever-widening gaps in coverage for

treatment, for prescriptions, for everything related to health care

costs. Even patients who have insurance and supposedly decent insurance

[come up short]. We’ve become an indispensable institution,

indispensable technology and indispensable platform for anyone who finds

themselves needing help because there just isn’t adequate coverage or

assistance.

I would love nothing more than for “medical” to not be a category on

GoFundMe. The reality is, though, that access to health care is

connected to the ability to pay for it. If you can’t do that, people

die. People suffer. We feel good that our platform is there when people

need it.

Q: Did anyone expect medical funding would become such a big part of GoFundMe?

I don’t think anyone anticipated it. What we realized early on is that medical need is a gigantic category.

A lot of insurance doesn’t cover clinical trials and research and

things like that, where people need access to leading-edge potential

treatments. We strive to fill these gaps until the institutions that are

supposed to handle this handle it properly. There has to be a

renaissance, a dramatic change in public policy, in how the government

focuses on this and how the health care companies solve this.

This is very interesting. In the places like the United Kingdom,

Canada and other European countries that have some form of universal or

government-sponsored health coverage, medical [costs] are still the

largest category. So it’s not just medical bills for treatment. There’s

travel and accommodations for families who have to support people when

they fall ill.

Q: What have you learned that you didn’t know before?

I guess what I realized [when I came] to this job is that I had no

notion of how severe the problem is. You read about the debate about

single-payer health care and all the issues, the partisan politics. What

I really learned is the health care system in the United States is

really broken. Way too many people fall through the cracks.

The government is supposed to be there and sometimes they are. The

health care companies are supposed to be there and sometimes they are.

But for literally millions of people they’re not. The only thing you can

really do is rely on the kindness of friends and family and community.

That’s where GoFundMe comes in.

I was not ready for that at all when I started at the company. When

you live and breathe it every day and you see the need that exists, when

you realize there are many people with rare diseases but they aren’t

diseases a drug company can make money from, they’re just left with

nothing.

Q: But what does this say about the system?

The system is terrible. It needs to be rethought and retooled.

Politicians are failing us. Health care companies are failing us. Those

are realities. I don’t want to mince words here. We are facing a huge

potential tragedy. We provide relief for a lot of people. But there are

people who are not getting relief from us or from the institutions that

are supposed to be there. We shouldn’t be the solution to a complex set

of systemic problems. They should be solved by the government working

properly, and by health care companies working with their constituents.

We firmly believe that access to comprehensive health care is a right

and things have to be fixed at the local, state and federal levels of

government to make this a reality.

Q: Do you ever worry that medical fundraising on your site is

taking away from other causes or other things that need to be funded?

We have billions being raised on our platform on an annual basis.

Everything from medical, memorial and emergency, to people funding

Little League teams and community projects.

Another thing that’s happened in the last few years is we’ve really

become the “take action button.” Whenever there’s a news cycle on

something where people want to help, they create GoFundMe campaigns.

This government shutdown, for example: We have over a thousand campaigns

right now for people who have been affected by it — they’re raising

money for people to pay rent, mortgages, car payments while the

government isn’t.

https://khn.org/news/gofundme-ceo-gigantic-gaps-in-health-system-showing-up-in-crowdfunding/

Can States Fix the Disaster of American Health Care?

by Elizabeth Rosenthal - NYT - January 17, 2019

Last week, California’s new governor, Gavin Newsom, promised to pursue

a smorgasbord of changes

to his state’s health care system: state negotiation of drug prices; a

requirement that every Californian have health insurance; more

assistance to help middle-class Californians afford it; and health care

for undocumented immigrants up to age 26.

The proposals fell short of the

sweeping government-run single-payer plan

Mr. Newsom had supported during his campaign — a system in which the

state government would pay all the bills and effectively control the

rates paid for services. (Many California politicians before him had

flirted with such an idea, before backing off when it was estimated that

it could

cost $400 billion

a year.) But in firing off this opening salvo, Mr. Newsom has

challenged the notion that states can’t meaningfully tackle health care

on their own. And he’s not alone.

A day later, Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington proposed that his state

offer a public plan, with rates tied to those of Medicare, to compete with private offerings.

New Mexico is

considering a plan

that would allow any resident to buy into the state’s Medicaid program.

And this month, Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York announced a plan to

expand health care access to uninsured, low-income residents of the

city, including undocumented immigrants.

For

over a decade, we’ve been waiting for Washington to solve our health

care woes, with endless political wrangling and mixed results. Around

70 percent of Americans

have said that health care is “in a state of crisis” or has “major

problems.” Now, with Washington in total dysfunction, state and local

politicians are taking up the baton.

The legalization of gay

marriage began in a few states and quickly became national policy.

Marijuana legalization seems to be headed in the same direction. Could

reforming health care follow the same trajectory?

States have

always cared about health care costs, but mostly insofar as they related

to Medicaid, since that comes from state budgets. “The interesting new

frontier is how states can use state power to change the health care

system,” said Joshua Sharfstein, a vice dean at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg

School of Public Health and a former secretary of the Maryland

Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. He added that the new proposals

“open the conversation about using the power of the state to leverage

lower prices in health care generally.”

Already states have proved

to be a good crucible for experimentation. Massachusetts introduced

“Romneycare,” a system credited as the model for the Affordable Care

Act, in 2006. It now has the lowest uninsured rate in the nation,

under 4 percent. Maryland has successfully regulated hospital prices based on an “all payer” system.

It

remains to be seen how far the West Coast governors can take their

proposals. Businesses — pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, doctors’

groups — are likely to fight every step of the way to protect their

financial interests. These are powerful constituents, with lobbyists and

cash to throw around.

The California Hospital Association

came out in full support

of Mr. Newsom’s proposals to expand insurance (after all, this would be

good for hospitals’ bottom lines). It offered a slightly less

enthusiastic endorsement for the drug negotiation program (which is less

certain to help their budgets), calling it a “welcome” development.

It’s notable that his proposals didn’t directly take on hospital

pricing, even though many of the state’s medical centers are notoriously

expensive.

Giving the state power to negotiate drug prices for

the more than 13 million patients either covered by Medicaid or employed

by the state is likely to yield better prices for some. But pharma is

an agile adversary and may well respond by charging those with private

insurance more. The governor’s plan will eventually allow some employers

to join in the negotiating bloc. But how that might happen

remains unclear.

The proposal by Governor Inslee of Washington to tie payment under the public option plans to Medicare’s rates drew “

deep concern”

from the Washington State Medical Association, which called those rates

“artificially low, arbitrary and subject to the political whims of

Washington, D.C.”

On the bright side, if Governor Newsom or

Governor Inslee succeeds in making health care more affordable and

accessible for all with a new model, it will probably be replicated one

by one in other states. That’s why I’m hopeful.

In 2004, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation conducted an

exhaustive nationwide poll

to select the greatest Canadian of all time. The top-10 list included

Wayne Gretzky, Alexander Graham Bell and Pierre Trudeau. No. 1 is

someone most Americans have never heard of: Tommy Douglas.

Tommy

Douglas, a Baptist Minister and left-wing politician, was premier of

Saskatchewan from 1944 to 1961. Considered the father of Canada’s health

system, he arduously built up the components of universal health care

in that province, even in the face of an infamous

23-day doctors’ strike.

In 1962, the province implemented a single-payer program of universal, publicly funded health insurance. Within a decade,

all of Canada had adopted it.

The

United States will presumably, sooner or later, find a model for health

care that suits its values and its needs. But 2019 may be a time to

look to the states for ideas rather than to the nation’s capital.

Whichever state official pioneers such a system will certainly be

regarded as a great American.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/16/opinion/california-states-health-care.html

Is the Drug Industry an Existential Threat to the Private Health Insurance Business?

by Robert Laszewski - Health Care Policy and Marketplace Review - January 16, 2019

At

a time when many Democrats are calling for a single-payer health

insurance system, are the drug companies inadvertently driving the

system on a course to that end?

Consider this.

The longtime

political firewall against a single-payer system has been the

satisfaction consumers have had with their employer-sponsored health

insurance. Most voters have had no interest in giving up their affordable and attractive employer

health benefits for the uncertainty of a one-size-fits-all

government-run plan.

Employer-sponsored health insurance covers

140 million people—by far the largest part of the under-age-65 health

insurance system. Most of these people are in the politically

all-important middle class.

But in recent years, the employer

share of premiums and out-of-pocket costs has been exploding (Willis

Towers Watson, November 2018):

- The unemployment rate is 3.7%—the lowest since 2000.

- But, corrected for inflation, wages are up only 2% since January 2015—about one-half of one percent annually.

- For

the bottom 60% of workers by income, wage gains have been completely

wiped out by contributions for employer-provided health insurance.

- For the bottom 50% of workers, employers’ health insurance contributions averaged 30% to 35% of the total compensation package.

- From

1999 to 2015, worker premiums for a family plan more than doubled in

inflation adjusted dollars, from $2,000 annually to $5,000.

In 2008, the average annual share of health insurance costs for employees was $3,354 but by 2018 that was up to $5,547:

Driving these costs has been pharmacy.

I recently polled a number of my clients on their historic and current drug spend.

- Twenty years ago, drug spend as a percentage of overall medical costs for a health insurer regularly ranged from 5% to 7%.

- Today, all drug costs, including specialty drugs and infusion drugs, range from 30% to 35% of all costs.

-

Today, employer plan health care cost trend is regularly reported by

health plans to be in the 5% to 7% range.

- When their drug cost trend is

subtracted from overall trend, non-drug trend is about 2%—essentially the

level of current overall inflation.

To me there is an inescapable set of conclusions here:

- Because

of the impact health insurance costs are having on take home income, we

are at risk that the historical attractiveness employees and their

families have had for employer-based health insurance will be lost.

- If

the health insurance industry loses the support of employer-plan

participants it will have lost the firewall that has made voters

reluctant to support government-run health care.

- The health plan

industry is providing health insurance to consumers for physician,

hospital, and related costs at an annual level of increase that is close

to overall inflation.

- With drug costs exploding from 5% to 7% of

total costs to now 30% to 35% of costs, the primary villain in the

multi-year erosion of the value of the employer-provided health benefit,

and private insurance generally, has been drug costs.

Voters,

Donald Trump, the Democrats, and the Republicans have all cited drug

costs as a huge economic issue that has to be brought under control.

But for the private health insurance industry, it could be the one major factor that does them in if a solution isn’t found.

I

can’t see a more important issue for the health insurance industry than

the unfettered ability of drug companies to unilaterally dictate

prices.

http://healthpolicyandmarket.blogspot.com/2019/01/is-drug-industry-existential-threat-to.html?

Learning From Cuba’s ‘Medicare for All’

by Nicholas Kristof - NYT - January 18, 2019

HAVANA — Claudia Fernández, 29, is an accountant whose stomach bulges with her first child, a girl, who is due in April.

Fernández lives in a cramped apartment on a potholed street and can’t afford a car. She also gets by without a meaningful vote or the right to speak freely about politics. Yet the paradox of Cuba is this: Her baby appears more likely to survive than if she were born in the United States.

Cuba is poor and repressive with a dysfunctional economy, but in health care it does

an impressive job that the United States

could learn from. According to official statistics (about which, as we’ll see, there is some debate), the infant mortality rate in Cuba is only 4.0 deaths per 1,000 live births. In the United States, it’s 5.9.

In other words, an American infant is, by official statistics, almost 50 percent more likely to die than a Cuban infant. By my calculations, that means that 7,500 American kids die each year because we don’t have as good an infant mortality rate as Cuba reports.

How is this possible? Well, remember that it may not be. The figures should be taken with a dose of skepticism. Still, there’s no doubt that a major strength of the Cuban system is that it assures universal access. Cuba has the Medicare for All that many Americans dream about.

“Cuba’s example is important since for decades ‘health care for all’ has been more than a slogan there,” said Dr. Paul Farmer, the legendary globe-trotting founder of Partners in Health. “Cuban families aren’t ruined financially by catastrophic illness or injury, as happens so often elsewhere in the neighborhood.”

In Havana, I shadowed a grass-roots doctor, Lisett Rodríguez, as she paid a house call on Fernández — and it was the 20th time Dr. Rodríguez had dropped in on Fernández’s apartment to examine her over the six months of her pregnancy. That’s on top of 14 visits that Fernández made to the doctor’s office, in addition to pregnancy consultations Fernández held with a dentist, a psychologist and a nutritionist.

This was all free, like the rest of the medical and dental system. It’s also notable that Cuba achieves

excellent health outcomes even though the

American trade and financial embargo

badly damages the

economy

and restricts access to medical equipment.

Fernández has received more attention than normal because she has hypothyroidism, making her pregnancy higher risk than average. Over the course of a more typical Cuban pregnancy, a woman might make 10 office visits and receive eight home visits.

Thirty-four visits, or even 18, may be overkill, but this certainly is preferable to the care common in, say, Texas, where one-third of pregnant women don’t get a single prenatal checkup in the first trimester.

Missing a prenatal checkup is much less likely in Cuba because of a system of front-line clinics called consultorios. These clinics, staffed by a single doctor and nurse, are often run down and poorly equipped, but they make health care readily available: Doctors live upstairs and are on hand after hours in emergencies.

They are also part of the neighborhood. Dr. Rodríguez and her nurse know the 907 people they are responsible for from their consultorio: As I walked with Dr. Rodríguez on the street, neighbors stopped her and asked her about their complaints. This proximity and convenience, and not just the lack of fees, make Cuba’s medical system accessible.

“It helps that the doctor is close, because transportation would be a problem,” Fernández told me.

Home visits are also a chance to reach elderly and disabled people and to coach dysfunctional families, such as those wracked by alcoholism (a common problem), and to work on

prevention. During Dr. Rodríguez’s visits to Fernández, for example, they discuss breast-feeding and how to make the home safe for the baby.

“It’s no secret that most health problems can be resolved at the primary-care level by the doctor, nurse or health worker nearest you,” said Gail Reed, the American executive editor of the health journal

Medicc Review, which focuses on Cuban health care. “So, there is something to be said for Cuba’s building of a national primary-care network that posts health professionals in neighborhoods nationwide.”

Each consultorio doctor is supposed to see every person in the area at least once a year, if not for a formal physical then at least to take blood pressure.

All this is possible because Cuba overflows with doctors — it has three times as many per capita as the United States — and pays them very little. A new doctor earns $45 a month, and a very experienced one $80.

The opening of Cuba to tourism has created some tensions. A taxi driver who gets tips from foreigners may earn several times as much as a distinguished surgeon. Unless, of course, that surgeon also moonlights as a taxi driver.

Critics inside and outside the country raise various objections to the Cuban system. Corruption and shortages of supplies and medicine are significant problems, and the health system could do more to address smoking and alcoholism.

There are also

allegations that Cuba fiddles with its numbers. The country has an unusually high rate of late fetal deaths, and skeptics contend that when a baby is born in distress and dies after a few hours, this is sometimes categorized as a stillbirth to avoid recording an infant death.

Dr. Roberto Álvarez, a Cuban pediatrician, insisted to me that this does not happen and countered with explanations for why the fetal death rate is high. I’m not in a position to judge who’s right, but any manipulation seems unlikely to make a huge difference to the reported figures.

Outsiders mostly say

they admire

the Cuban health system. The World Health Organization has

praised it, and Ban Ki-moon, the former United Nations secretary general,

described it as “a model for many countries.”

In many ways, the Cuban and United States health care systems are mirror opposites. Cuban health care is dilapidated, low-tech and free, and it is very good at ensuring that no one slips through the cracks. American medicine is high-tech and expensive, achieving some extraordinary results while stumbling at the basics: A lower percentage of children are vaccinated in the United States than in Cuba.

The difference can also be seen in treatment of cancer. Cuba regularly screens all women for breast and cervical cancer, so it is excellent at finding cancers — but then it lacks enough machines for radiation treatment. In the United States, on the other hand, many women don’t get regular screenings so cancers may be discovered late — but then there are advanced treatment options.

As Cuba’s population becomes older and heavier (as in the United States, the nutrition problem here is people who are overweight, not underweight), heart disease and cancer are becoming more of a burden. And the lack of resources is a major constraint in treating those ailments.

There’s a Cuban saying: “We live like poor people, but we die like rich people.”

New poll reveals most Democrats are willing to pay Medicare for all tax

by Diane Archer - Just Feed - January 16, 2019

Pundits suggest that one of the biggest challenges to enacting

Medicare for All is that the public will object to paying additional

public taxes for their health care. But, is that really a challenge? A

new

Harvard/POLITICO poll shows that more than 80 percent of Democrats are willing to pay the Medicare for all tax.

With

Medicare for All,

people would stop paying a high private tax–premiums, deductibles and

coinsurance for their health care. Indeed, eight in ten Americans would

pay less for their health care. Only the wealthiest Americans would pay more.

The poll also shows that:

- More than four in ten Democrats support repealing and replacing the

Affordable Care Act. Their goal is to ensure coverage for everyone. The

ACA, which relies on the states to administer health exchanges, and

commercial insurers to provide coverage, will never deliver the good

affordable care we all need. Today, millions of Americans are still

uninsured and millions with coverage struggle to afford needed care.

- A solid majority of Republicans (60 percent) now support letting

people under 65 buy into Medicare. The poll did not ask whether they

supported Medicare for All to everyone. Curiously, fewer Republicans–51

percent–support a public health insurance option than a Medicare

buy-in. They are one and the same thing, two different ways of

describing a Medicare option.

- Republicans and Democrats alike want Congress to lower prescription drug prices.

It remains a top priority for Americans. More than nine in ten (92

percent) say it is very important (94 percent of Democrats and 89

percent of Republicans).

- Republicans and Democrats alike want to ensure coverage for people with pre-existing conditions.

- And, people in both parties do not want to see cuts to Medicare

(more than nine in ten Democrats (93 percent) and nearly eight in ten

Republicans.) Republicans in Congress who are eyeing Medicare cuts as a

way to address the deficit should take note.

The mid-December poll surveyed 1,013 adults.

http://justcareusa.org/new-poll-reveals-most-democrats-are-willing-to-pay-medicare-for-all-tax/?