Hospital Letter Urging Patient to Start 'Fundraising Effort' to Pay for Heart Treatment Seen as Yet Another Reason America Needs Medicare for All

"'You can't have a heart unless you do GoFundMe for 10K' is not a just

by Jake Johnson - Common Dreams - November 24, 2018

Hospital Letter Urging Patient to Start 'Fundraising Effort' to Pay for Heart Treatment Seen as Yet Another Reason America Needs Medicare for All

"'You can't have a heart unless you do GoFundMe for 10K' is not a just system."

As progressive lawmakers and healthcare experts have frequently pointed out in recent months, few growing trends have laid bare the fundamental immorality and brokenness of America's healthcare system quite like the rise of GoFundMeand other crowdfunding platforms as methods of raising money for life-saving medical treatments that—due to insurance industry greed and dysfunction—are far too expensive for anyone but the very wealthiest to afford.

"Insurance groups are recommending GoFundMe as official policy—where customers can die if they can't raise the goal in time—but sure, single-payer healthcare is unreasonable."

—Rep.-elect Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

—Rep.-elect Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

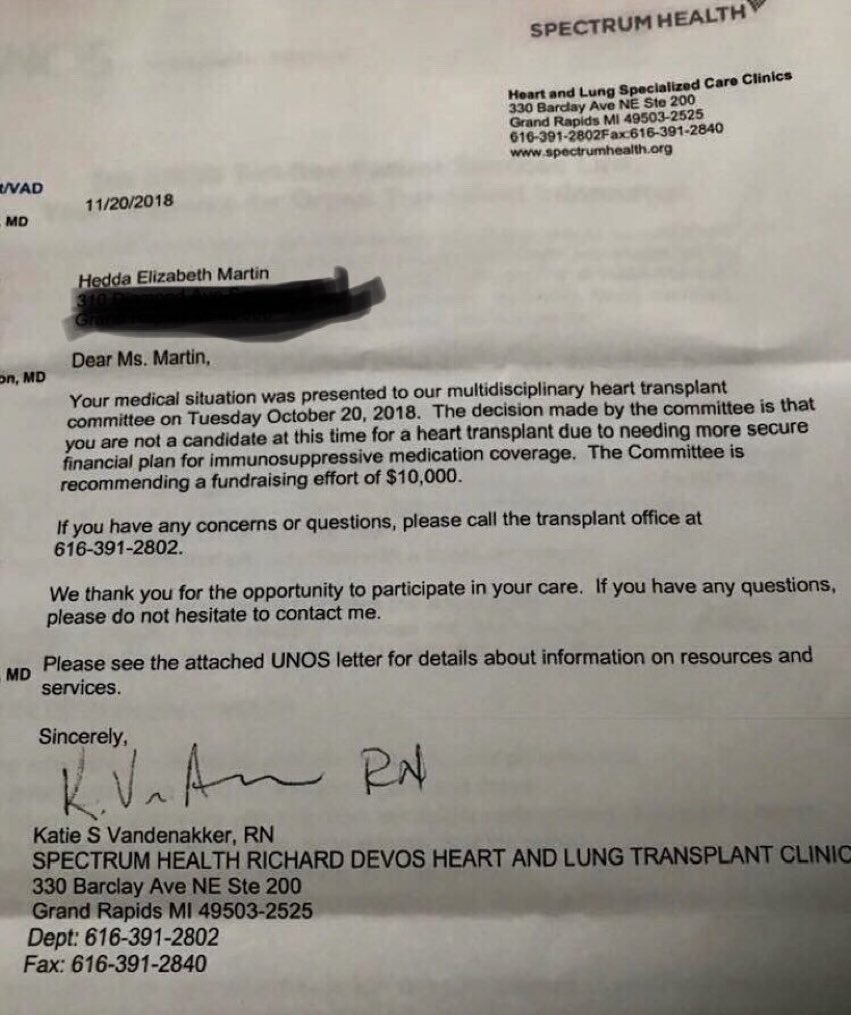

Providing the latest example of this horrifying trend, a Michigan woman seeking a heart transplant publicized a letter she received from the Spectrum Health Richard DeVos Heart and Lung Transplant Clinic—named after the late father-in-law of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos—informing her that she is "not a candidate" for the procedure "at this time" because she needs a "more secure financial plan" to afford the required post-operation immunosuppressive medication.

The letter goes on to explicitly recommend "a fundraising effort of $10,000" to help pay for the drugs.

Hedda Elizabeth Martin, who posted the letter on Facebook, wrote that her situation encapsulates America's "price gouging, horribly overpriced, underinsured system," which affects millions each day in the richest country on Earth.

The letter, which Martin received shortly before Thanksgiving, began to go viral on Saturday and quickly caught the attention of progressives like Rep.-elect Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), who identified Martin's situation as indicative of the broad failure of America's healthcare status quo—which produces tremendous profits for insurance and pharmaceutical giants and worse outcomes than the healthcare systems of other industrialized nations.

"Insurance groups are recommending GoFundMe as official policy—where customers can die if they can't raise the goal in time—but sure, single-payer healthcare is unreasonable," Ocasio-Cortez, an unabashed supporter of Medicare for All, wrote sarcastically.

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2018/11/24/hospital-letter-urging-patient-start-fundraising-effort-pay-heart-treatment-seen-yet

To patients’ surprise, a visit to urgent care brings steep hospital bill

States Are Not Waiting on Congress to Expand Medicare to Cover Everybody

by Wendell Potter - Tarbell.org - August 10, 2018

With all the buzz over the past year about the United States moving to a Medicare-for-all type of health care system, what has not been talked about nearly as much are the different paths we as a country could take to get there.

While Medicare-for-all bills in Congress have made headlines, far less attention has been focused on legislation that would create state-based publicly financed health care systems.

It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that a state could lead the way. That’s exactly what happened in Canada back in the 1960s. It wasn’t federal lawmakers in Ottawa who got the ball rolling up there. It was the premier of Saskatchewan, thousands of miles to the west.

If that’s how it takes off here, which state will be our Saskatchewan?

It very possibly could be New York.

The New York State Assembly passed a bill in June that would provide comprehensive coverage for all New Yorkers. Although the bill, the New York Health Act, has not yet passed the Senate, it got a big boost a few days ago when the RAND Corporation, a global nonprofit policy think tank, released a study showing that the state’s residents, millions of whom are either uninsured or underinsured, would get better coverage—and pay less for it—if the bill became law. Overall, RAND said, the state would save an estimated $15 billion annually after 10 years compared with what it would spend under the current system.

Not only would most New Yorkers save money, their coverage would be considerably more comprehensive. Almost all health care services, including dental and vision, would be covered. (Long-term care is not currently in the bill, but the RAND study said it could be included and still cost less than the status quo after ten years.) Out of pocket spending would be cut in half.

According to RAND, much of the savings would come from lower administrative costs. Because of our current mix of public and private payers, the United States spends far more on health care administration than any other developed country. RAND found that the New York Health Act would reduce administrative costs by $23 billion. That’s to a large extent what would enable the state to cover everyone and provide them with richer benefits. RAND said the state would actually spend $9 billion more on care than if the current system is still in place.

The results of the study came as welcome news to the bill’s sponsors, Assembly Health Committee Chair Richard Gottfried and State Sen. Gustavo Rivera.

“This is an important validation of the New York Health Act by one of the most prestigious analytical firms in the country,” Gottfried said in a statement. “RAND shows we can make sure every New Yorker gets the care they need and does not suffer financially to get it, save billions of dollars a year by cutting administrative costs, insurance company profit, and outrageous drug prices, and pay for it all more fairly.”

Rivera said he believes the savings and benefits would actually be greater than what RAND estimates. He also noted that RAND found that the bill would also create new jobs in the state.

Under the bill’s public financing of coverage, premiums that individuals and corporations now pay would be in the form of taxes. As Vox reporter Dylan Scott noted in a recent analysis of the RAND study, the “new tax payments would almost perfectly replace the premiums that people and their employers pay right now for private health insurance.”

While the great majority of New Yorkers would pay less for coverage if the law is enacted, people with incomes in the top 10 percent likely would pay more. As Jodi Liu, the associate policy researcher at RAND who led the study, noted, the progressive nature of the funding mechanism will not be without detractors. “One of the biggest challenges could be the design of the tax schedule, as policymakers seek a balance between affordability for lower- and middle-income households and potential tax avoidance behaviors by higher-income households.”

The RAND study was commissioned by the New York State Health Foundation.

LePage plans to appeal court order for immediate steps to expand Medicaid

by Scott Thistle - Portland Press Herald - November 21, 2018

Justice Michaela Murphy says the governor can't ignore the will of the people who passed the law extending health care coverage to as many as 80,000 low-income Mainers.

Gov. Paul LePage plans to appeal a judge’s order that his administration immediately move forward with a voter-approved expansion of MaineCare, the state’s Medicaid system.

Kennebec County Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy issued the order Wednesday, detailing seven steps the Maine Department of Health and Human Services must take to comply with the expansion law, which extends health care coverage to as many as 80,000 low-income Mainers. The law was approved by 59 percent of the state’s voters in November 2017, but LePage repeatedly has blocked implementation by vetoing legislation to fund the expansion and refusing to take administrative steps.

“Although the governor may believe implementation to be unwise and disagree with the (expansion law) as a matter of policy, he may not ignore the will of the people and refuse to take any action toward accomplishing the policy objectives of the (law),” Murphy wrote in her 21-page order.

LePage spokeswoman Julie Rabinowitz said in an email Wednesday that the governor plans to appeal Murphy’s order.

Governor-elect Janet Mills, a Democrat, has said she will make expansion of Medicaid under the voter-approved law the first priority for her administration when she takes office in January.

Murphy’s order, retroactive to July 2, requires the DHHS to file an amendment to paperwork already submitted to the federal government. The amendment must state that there are no legal or constitutional grounds for delaying the expansion. In the initial paperwork filed by the DHHS, during a process known as a state plan amendment or SPA, the LePage administration urged the federal Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services to reject the state’s application.

The order directs acting DHHS Commissioner Bethany Hamm to “amend the eligibility SPA it submitted to the federal government on September 4, 2018, to reflect an effective date of the Expansion Act to be January 3, 2018; the effective date requiring coverage to be July 2, 2018; and to inform CMS that no constitutional or statutory impediment exists which prevents the commissioner from using existing appropriations to implement the Expansion Act. The commissioner must further take all necessary steps to ensure that approval of the SPA is retroactive to July 2, 2018.”

The order gives DHHS until Dec. 5 to comply.

WIN FOR VOTERS, RULE OF LAW

Robyn Merrill, executive director of Maine Equal Justice Partners, which sued LePage over his delays in implementing the law, called Murphy’s order a “huge victory” for the thousands of Mainers who have “been unfairly denied health care.”

“This is also a victory for the Maine voters and for the rule of law,” Merrill said in a written statement. “The executive branch has a duty to carry out all the laws, not pick and choose, and today’s ruling holds them accountable.”

In August, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court ruled against the administration when it sought to delay implementation of the expansion until the Legislature funded the state’s cost, estimated to be about $55 million a year.

Under the law, Mainers earning as much as 138 percent of the federal poverty level – $16,753 for an individual and $34,638 for a family of four – could begin applying for Medicaid coverage on July 2. Many did, only to receive letters of denial from DHHS.

“The governor’s excuses and obstructionism did not hold water with the courts,” Merrill said.

Jack Comart, litigation director for Maine Equal Justice Partners, said Wednesday that the practical implications of Murphy’s order for those who are eligible for MaineCare services under the law is that any covered services should be paid by the state and any costs they incurred with health care providers that accept Medicaid should be reimbursed. Comart said that anyone who was eligible for services as of July 2 should be reimbursed by the state if they paid for their medical costs out of pocket.

“This is tremendous news for anyone who applied for or was terminated from MaineCare on or after July 2 who meets the eligibility requirements for the expansion group,” Comart said. “The court now says that these people should receive MaineCare right away, whether or not the federal application for funds has been approved. We see no impediment to Maine receiving that approval, but as the court said, it will not hold up care for people who have already waited a long time.”

LEPAGE: ‘NOBODY CAN FORCE ME’

Comart said he did not believe that President Trump’s recent appointment of Mary Mayhew – the former DHHS commissioner under LePage – to head the federal CMS would have any bearing on whether the federal government approves Maine’s expansion plan or not.

Though LePage has argued that expansion was not funded by the Legislature, he vetoed a funding bill approved by lawmakers and the Legislature failed to override the veto in a July 9 vote.

LePage has consistently opposed Medicaid expansion, arguing that doing so would be financially disastrous for the state. In June, he said the Legislature’s $60 million funding bill contained “unsustainable budget gimmicks,” and he vetoed it. Before the ballot measure passed into law, LePage successfully vetoed legislation to expand the system five times. Once he even held a news conference to ceremonially veto an expansion bill even before it reached his desk.

And on a July radio show, LePage said he would rather go to jail than implement the expansion law because of his concerns about the potential impact on the state budget.

“The one thing I know is nobody can force me to put the state in red ink, and I will not do that,” the Republican said at the time. “I will go to jail before I put the state in red ink. And if the court tells me I have to do it, then we’re going to be going to jail.”

Mills, currently the state’s attorney general, has refused to represent the LePage administration in its legal efforts to stop implementation and instead sided with the plaintiffs in the case by filing an amicus brief in support of the expansion law in October.

Mills’ office did authorize LePage to hire a private attorney to defend the administration against the suit. Murphy previously rejected a separate court complaint that LePage brought against Mills over the costs to taxpayers of hiring outside counsel. Those costs, according to state records obtained by the Associated Press, likely exceed $200,000.

“This decision is a victory for the people of Maine,” Mills said of Murphy’s order in a statement issued Wednesday. “Medicaid expansion is the law of the land, and, as governor, I will implement the law.

“Not only will Medicaid expansion result in health care for tens of thousands of Mainers, it will also reduce health insurance costs, support small businesses, bolster our rural hospitals, and create jobs to expand our economy.”

Sanders unveils aggressive new bill targeting drug prices

by Peter Sulliven - The Hill - November 20, 2018

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) on Tuesday unveiled a bill aimed at aggressively lowering drug prices by stripping monopolies from drug companies if their prices are deemed excessive.

Sanders has long railed against drug companies for their prices, and this bill is one of the most far-reaching proposals aimed at lowering them.

The bill would strip the monopoly from a company, regardless of any patents, and allow other companies to create cheaper generic versions of a drug if the price for that drug is higher than the median price in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Japan.

“No other country allows pharmaceutical companies to charge any price they want for any reason they want,” Sanders, who could run for president again in 2020, said in a statement.

“The greed of the prescription drug industry is literally killing Americans and it has got to stop,” he added.

Drug companies argue that other countries, with price controls, lack the innovation that happens in the United States.

The bill does not have a clear path forward in the next two years, given that Republicans will still control the Senate.

But the measure shows how far progressives want to go on drug pricing and comes at a time when there is growing momentum for taking some action on the issue, even if it might not be as far-reaching.

President Trump has also focused on lowering the price of drugs, and Democrats hope to be able to work with him in a bipartisan way.

Khanna, a progressive who represents Silicon Valley, joins Sanders on the bill.

“Today, we’re sending big pharma a message: Market exclusivity is a privilege, and when you abuse that by price gouging the sick and aging, then you lose that privilege,” Khanna said.

https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/417570-sanders-unveils-aggressive-new-bill-targeting-drug-prices?

Trump Administration Invites Health Care Industry to Help Rewrite Ban on Kickbacks

by Robert Pear - NYT - November 24, 2018

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration has labored zealously to cut federal regulations, but its latest move has still astonished some experts on health care: It has asked for recommendations to relax rules that prohibit kickbacks and other payments intended to influence care for people on Medicare or Medicaid.

The goal is to open pathways for doctors and hospitals to work together to improve care and save money. The challenge will be to accomplish that without also increasing the risk of fraud.

With its request for advice, the administration has touched off a lobbying frenzy. Health care providers of all types are urging officials to waive or roll back the requirements of federal fraud and abuse laws so they can join forces and coordinate care, sharing cost reductions and profits in ways that would not otherwise be allowed.

From hundreds of letters sent to the government by health care executives and lobbyists in the last few weeks, some themes emerge: Federal laws prevent insurers from rewarding Medicare patients who lose weight or take medicines as prescribed. And they create legal risks for any arrangement in which a hospital pays a bonus to doctors for cutting costs or achieving clinical goals.

The existing rules are aimed at preventing improper influence over choices of doctors, hospitals and prescription drugs for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. The two programs cover more than 100 million Americans and account for more than one-third of all health spending, so even small changes in law enforcement priorities can have big implications.

Federal health officials are reviewing the proposals for what they call a “regulatory sprint to coordinated care” even as the Justice Department and other law enforcement agencies crack down on health care fraud, continually exposing schemes to bilk government health programs.

“The administration is inviting companies in the health care industry to write a ‘get out of jail free card’ for themselves, which they can use if they are investigated or prosecuted,” said James J. Pepper, a lawyer outside Philadelphia who has represented many whistle-blowers in the industry.

Federal laws make it a crime to offer or pay any “remuneration” in return for the referral of Medicare or Medicaid patients, and they limit doctors’ ability to refer patients to medical businesses in which the doctors have a financial interest, a practice known as self-referral.

These laws “impose undue burdens on physicians and serve as obstacles to coordinated care,” said Dr. James L. Madara, the chief executive of the American Medical Association. The laws, he said, were enacted decades ago “in a fee-for-service world that paid for services on a piecemeal basis.”

Melinda R. Hatton, senior vice president and general counsel of the American Hospital Association, said the laws stifle “many innocuous or beneficial arrangements” that could provide patients with better care at lower cost.

Hospitals often say they want to reward doctors who meet certain goals for improving the health of patients, reducing the length of hospital stays and preventing readmissions. But federal courts have held that the anti-kickback statute can be violated if even one purpose of the remuneration is to induce referrals or generate business for the hospital.

The premise of the kickback and self-referral laws is that health care providers should make medical decisions based on the needs of patients, not on the financial interests of doctors or other providers.

The Trump administration is calling its effort a “regulatory sprint to coordinated care.”Sarah Silbiger/The New York Times

Health care providers can be fined if they offer financial incentives to Medicare or Medicaid patients to use their services or products. Drug companies have been found to violate the law when they give kickbacks to pharmacies in return for recommending their drugs to patients. Hospitals can also be fined if they make payments to a doctor “as an inducement to reduce or limit services” provided to a Medicare or Medicaid beneficiary.

Doctors, hospitals and drug companies are urging the Trump administration to provide broad legal protection — a “safe harbor” — for arrangements that promote coordinated, “value-based care.” In soliciting advice, the Trump administration said it wanted to hear about the possible need for “a new exception to the physician self-referral law” and “exceptions to the definition of remuneration.”

Almost every week the Justice Department files another case against health care providers. Many of the cases were brought to the government’s attention by people who say they saw the bad behavior while working in the industry.

“Good providers can work within the existing rules,” said Joel M. Androphy, a Houston lawyer who has handled many health care fraud cases. “The only people I ever hear complaining are people who got caught cheating or are trying to take advantage of the system. It would be disgraceful to change the rules to appease the violators.”

But the laws are complex, and the stakes are high. A health care provider who violates the anti-kickback or self-referral law may face business-crippling fines under the False Claims Act and can be excluded from Medicare and Medicaid, a penalty tantamount to a professional death sentence for some providers.

Federal law generally prevents insurers and health care providers from offering free or discounted goods and services to Medicare and Medicaid patients if the gifts are likely to influence a patient’s choice of a particular provider. Hospital executives say the law creates potential problems when they want to offer social services, free meals, transportation vouchers or housing assistance to patients in the community.

Likewise, drug companies say they want to provide financial assistance to Medicare patients who cannot afford their share of the bill for expensive medicines.

AstraZeneca, the drug company, said that older Americans with drug coverage under Part D of Medicare “often face prohibitively high cost-sharing amounts for their medicines,” but that drug manufacturers cannot help them pay these costs. For this reason, it said, the government should provide legal protection for arrangements that link the cost of a drug to its value for patients.

Even as health care providers complain about the broad reach of the anti-kickback statute, the Justice Department is aggressively pursuing violations.

A Texas hospital administrator was convicted in October for his role in submitting false claims to Medicare for the treatment of people with severe mental illness. Evidence at the trial showed that he and others had paid kickbacks to “patient recruiters” who sent Medicare patients to the hospital.

The owner of a Florida pharmacy pleaded guilty last month for his role in a scheme to pay kickbacks to Medicare beneficiaries in exchange for their promise to fill prescriptions at his pharmacy.

The Justice Department in April accused Insys Therapeutics of paying kickbacks to induce doctors to prescribe its powerful opioid painkiller for their patients. The company said in August that it had reached an agreement in principle to settle the case by paying the government $150 million.

The line between patient assistance and marketing tactics is sometimes vague.

This month, the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services refused to approve a proposal by a drug company to give hospitals free vials of an expensive drug to treat a disorder that causes seizures in young children. The inspector general said this arrangement could encourage doctors to continue prescribing the drug for patients outside the hospital, driving up costs for consumers, Medicare, Medicaid and commercial insurance.